JetBlue: Balancing growth, margins and ROIC

March 2012

JetBlue is the only one of the top six US carriers that has stepped up growth in the past two years: its ASMs rose by 6.7% in 2010 and by 7.2% in 2011. This year’s plans call for similar 5.5-7.5% growth, which contrasts with the flat capacity or 2-3% reductions projected by other large US carriers.

The reason is simple: JetBlue has had “once in a lifetime” type growth opportunities as a result of legacy carrier withdrawal from many of its core markets. American has contracted sharply in Boston and the Caribbean as it has shifted capacity to its five “cornerstone” markets (New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Dallas and Miami). Delta and US Airways, too, have retreated in the Caribbean to focus on business markets. Some of the Caribbean flags, including Air Jamaica, have also reduced capacity in competitive JetBlue markets.

According to JetBlue, since 2007 other airlines’ capacity has declined by 70% or more in 21 markets out of Boston and in 14 US-Caribbean markets. The past year has also seen significant service cuts by competitors in the Puerto Rico market.

JetBlue has also benefited from continued capacity restraint in the transcontinental market, which still account for 32% of its ASMs. And now capacity is even coming down in JetBlue’s traditional NE-Florida stronghold (also 32% of its ASMs).

So, JetBlue has enjoyed a rare respite on the competitive front. And it has been able to grow aggressively in Boston and in the Caribbean without adding to industry capacity.

But, as it has tapped the growth opportunities, JetBlue has gone a step further: it has aggressively sought to capture business traffic in Boston. This is a new strategy for the carrier. It is one thing for an LCC to attract business travellers because they like your product and service. It is an entirely different thing to go out there and adopt legacy strategies, as JetBlue has done: try to clinch

This strategy is interesting, first, because it is limited to the Boston market. Everywhere else JetBlue remains “primarily a leisure player”. In New York, its home base which accounts for most of its revenues, the airline has made a “conscious decision not to focus on the business traveller” (as one of its top executives put it). So JetBlue is New York’s hometown leisure airline, but 190 miles northeast it is positioning itself as Boston’s hometown business airline.

The Boston business strategy is also controversial for an LCC from the viewpoint of keeping costs low. Will JetBlue be able to execute the strategy without ending up with a legacy-style cost structure?

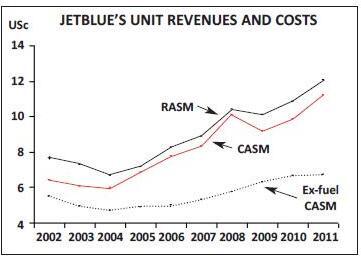

The Boston strategy, together with JetBlue’s other notable recent activities – aggressive Caribbean expansion, international alliance building and new up-market ancillary offerings – are certainly paying dividends in terms of revenue generation. JetBlue has outperformed the industry in terms of RASM growth since 2007.

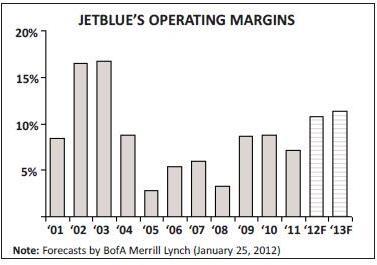

JetBlue’s operating margins have also remained healthy: 8.7% in 2009, when much of the rest of the US industry lost money, followed by 8.8% and 7.1% margins in 2010 and 2011.

But JetBlue has lagged behind its peers in terms of net margins (a meagre 2.6% in 2010, followed by 1.9% last year) and ROIC (4% in 2011). With many US airlines now focusing on ROIC, JetBlue has taken much criticism from analysts and investors for continuing to focus on growth and for incurring relatively high capital spending in the face of low returns.

Some analysts have also questioned why JetBlue has not been able to cash in more quickly on the Boston opportunities and the easier competitive environment. They have

Not surprisingly, JetBlue’s management decided that this was a good time to explain the network and financial strategies in greater depth and hopefully allay any investor fears. The airline held an analyst day on February 15 — for the first time since 2008 – and indicated that from now on it would be an annual event.

The key messages conveyed by the management at the New York event were, first, that JetBlue is still a growth company but that it is committed to sustainable growth. ASM growth is now moderating slightly and should average in the “mid single-digits” over the longer term.

Second, JetBlue continues to focus on financial discipline. It has now set actual targets for ROIC improvement and intends to be “laser-focused” on ex-fuel CASM. It has one of the highest cash balances in the industry (28% of annual revenues). Its debt load is high, but it is pursuing opportunities to prepay debt and wants to continue funding expansion with operating cash.

The third important message was that the Boston network is now reaching a certain level of maturation, enabling JetBlue to start reaping financial benefits. The executives stated: “We really are reaching a tipping point in some of the network investments we made”.

The management went to some lengths to explain why the Boston business strategy makes great sense to JetBlue. Among other things, it has enabled the airline to reduce the severe seasonality associated with its leisure-oriented network.

Of course, the Boston investments are for the longer term – a concept analysts and investors do not always appreciate. Amazingly, it takes 2-3 years to make a typical Boston business market profitable, whereas many of the Caribbean leisure/VFR markets are profitable almost immediately.

The management also sought to “lift the cloaks of secrecy about partnerships a bit” (though no earth-shattering secrets were revealed).

One of the most interesting parts was the discussion on culture and the value of a highly engaged workforce – often the only thing that differentiates airlines from the customer viewpoint. JetBlue goes to great lengths to maintain its culture and is using highly sophisticated techniques to measure it and how it builds customer loyalty.

From high growth to ROIC

The management came up with a catchy phrase to summarise JetBlue’s evolution in its 12-year history: “From growing fast, to growing up, to growing profitably”.

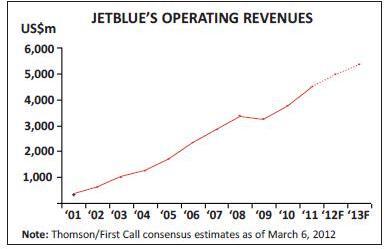

Initially, it was all about fast growth. JetBlue, which began operations in February 2000, made the most of its ample start-up funds and promising niche at JFK by growing extremely rapidly. It went public after only two years, earned spectacular 17% operating margins in 2002 and 2003 and achieved “major carrier” status (with $1bn-plus annual revenues) in its fifth year.

But JetBlue then stumbled financially, seeing its operating margin plummet to the low single-digits and net results turn negative in 2005 and 2006. Much of it was blamed on over-aggressive expansion. In 2006 JetBlue took delivery of an aircraft every 10 days and added 16 new cities to its network. In the previous year it launched a new aircraft type (the E190).

Consequently, in 2007-2008 JetBlue shifted its focus from growth to liquidity. It acted quickly to curtail capacity growth and brought capital spending to relatively modest levels through aircraft sales, lease terminations and order deferrals.

However, JetBlue continued to invest in critical areas. For example, it realised that to make it as New York’s hometown airline, it needed the right infrastructure – hence JFK’s Terminal 5, a world-class modern facility that opened in 2008. Another example was the transition to Sabre in 2010.

Also, in 2008-2009, when its total ASMs remained relatively flat, JetBlue was able to expand quite rapidly in the Caribbean by reallocating capacity from less profitable markets, such as the transcon.

The focus on liquidity and other new strategies were facilitated by a leadership change, which resulted from an operational meltdown JetBlue suffered in early 2007. President Dave Barger took over as CEO from the visionary founder David Neeleman. In the subsequent two years the remaining slate of top officers also changed.

As a result, JetBlue returned to “mainstream” operating margins in 2007 and 2008. It outperformed the industry in 2009, when its legacy peers were hit hard by the global recession. And JetBlue has now generated positive free cash flow (FCF) for three consecutive years (2009, 2010 and 2011).

Now the focus has shifted to ROIC, reflecting what the executives described as an “industry-wide return to ROIC metrics”. For JetBlue this will mean slightly lower ASM growth and striving to improve the ROIC by “at least a point per year” (to 5% in 2012, 6% in 2013 and so on). The ROIC target is very modest by legacy standards, but the executives noted that JetBlue is younger and has a different business model.

But it was also reassuring to hear that JetBlue remains a “contrarian airline”. It has always done things a little differently. Originally many people argued that an LCC could never be successful at JFK because of the ATC congestion, harsh winter weather, high cost levels and difficulty of recruiting the right kind of employees in the Northeast. Many people also regarded leather seats, LiveTV at altitude and a second fleet type as crazy ideas for an LCC. But JetBlue proved wrong all the sceptics and many of its ideas have been copied by other airlines.

On the cost front, though, JetBlue faces significant challenges, particularly with maintenance costs due to the gradual aging of the fleet. Its aircraft utilisation has also declined due to increased shorter-haul flying in Boston and San Juan. On the positive side, it has retained a non-unionised, highly flexible and productive workforce (helped by a strict no-furlough policy).

JetBlue is monitoring its narrowing ex-fuel CASM advantage over the legacy carriers, though it still has a very competitive cost position today. Trying to be a growing airline with essential infrastructure projects to complete is a tough comparison with those that have gone through a restructuring or are getting synergies through mergers. JetBlue is also more up-market than other LCCs and has Northeast cost levels. But JetBlue knows that it has to maintain its cost advantage, so it is in the process of evaluating almost everything it does for potential cost savings. To set an example, there is a management hiring and salary freeze currently in place.

The Boston opportunity

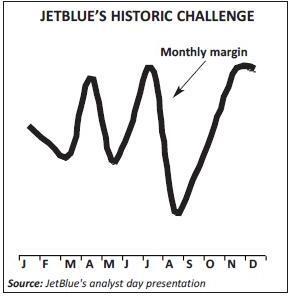

JetBlue was founded on a core leisure market (Northeast-Florida and transcon), which meant strong peak performance but terrible seasonal troughs. The network performed well initially, but with growth the problem with the troughs became worse and JetBlue knew that it had to start reducing seasonality both in terms of where it flew and, more importantly, the type of customer.

The solution has been twofold. First, about three years ago JetBlue began tapping the business market in Boston, a city it had served since 2004. Second, as it has grown in the US-Caribbean leisure market, JetBlue has sought markets with a high VFR traffic component, which is slightly less seasonal and more recession-resistant than pure leisure traffic.

Much of the discussion at the analyst day focused on the Boston business market. The opportunity came about because of the across-the-board contraction of legacy carriers in Boston – a trend that apparently continues in 2012 with competitor capacity declining in the Boston-Orlando market this summer. JetBlue executives also noted that Boston had been a “fragmented” market for a long time; it never had a dominant carrier, which for a newcomer meant a “relatively low cost of entry going in and growing it”.

So JetBlue spotted an opportunity and seized it. Since 2007 it has entered or doubled capacity in 27 markets out of Boston (17 US and 10 Caribbean cities). It now serves 45 points from Boston on a nonstop basis, both business and leisure markets, with the 46th destination (Dallas) being added in May.

JetBlue is already the largest airline at Boston Logan, having grown its seat share from 12% in 2Q07 to 23% in 2Q12. In the same period, Delta’s seat share declined from 22% to 15%, American’s from 16% to 11% and US Airways’ from 18% to 15%. Moreover, the legacy carriers serve a much more limited number of destinations than JetBlue.

Despite the rapid growth, JetBlue has outperformed competitors on a unit revenue basis in Boston. Between 2007 and 2011, its RASM increased by 14%, compared to a 9% increase for other carriers, even as JetBlue’s seats in those markets grew by 83% and other carriers’ declined by 10%. Such a performance is a major feat; JetBlue executives put it down to the “power of our brand in the Boston area”. It should also be noted that total industry seats in the Boston market grew by just 2% in that period, so JetBlue was not really adding incremental capacity to the market.

The RASM trends reflect JetBlue’s growing premium traffic market share in Boston. The airline estimates that nearly 30% of its customers in Boston are travelling on business, compared to 20% in the rest of its network. In top business markets, such as Boston-Newark, business customers account for almost half of total traffic and up to 66% of revenues (JetBlue defines business travel as purchase within seven days of travel and no Saturday nights).

In order to be truly attractive to the corporate traveller in the Boston area, JetBlue realised that it needed to build a sizable network, covering all the key business destinations, and a competitive schedule throughout the day. Even though its overall growth in Boston has been rapid, JetBlue has only been adding 1-2 business markets per year, so that there is not too much of a drain on profitability. The management feels that it was only really last year that, for the first time, JetBlue had the schedule and the network in Boston that would be of interest to the vast majority of its corporate customers.

Another challenge is that many of the corporate contracts are on 2-3 year cycles, so if JetBlue now has a product of interest, it can take up to three more years to clinch those contracts.

Maintaining low costs is a very important consideration. As one example, JetBlue has only one account manager in Boston to oversee a large number of corporate contracts; one of its former (smaller) competitors had five.

But JetBlue is spending where it matters, be it system upgrades, additional gates or remodelling facilities to make them more acceptable to business customers. Participating in GDSs has made a big difference. The yields that JetBlue gets through that channel are on average $35-40 higher than what it gets through its website.

JetBlue also has attractive basic offerings to the business customer, some of which provide additional revenue streams. The mantra is to “keep it simple” and provide only the products and services that customers really value. JetBlue offers free LiveTV and “the most legroom in coach of any US airline”. One of its most successful ancillary offerings is “Even more Space”, a “front cabin” product introduced in 2008 that costs hardly anything to deliver but it generated $120m in 2011. JetBlue is currently rolling out “Even More Speed”, a priority security lane at airports. Two years ago JetBlue revamped its TrueBlue loyalty programme.

In its dealings with corporations in Boston, JetBlue takes pride in being “easy to negotiate with”. It does want to negotiate the right price, but it is not bound by rules on corporate deals and so can be more flexible.

On the negative side, JetBlue has found that the Boston business markets take quite a bit longer to mature than its traditional leisure/VFR markets. In a typical Boston business market, the first year is lossmaking, the second year roughly breakeven and the third year profitable.

Of course, JetBlue has also continued to grow in the Caribbean/Latin America region; since 2007 it has entered or doubled capacity in 17 markets. The region will account for 27% of JetBlue’s ASMs in 2012, up from 6.4% in 2005. JetBlue has taken a “hedged position” in that region in terms of seeking exposure to both VFR and package holiday markets. The routes are profitable almost immediately and reach maturity quickly. JetBlue’s RASM outperformance in that region has been even stronger than in Boston: between 2007 and 2011, its RASM was up by 41% (versus competitors’ 28%), even as its seats surged by 210%, compared to other airlines’ 12% reduction in JetBlue markets.

The good news is that the new network strategies, especially the growth in Boston, are having the desired impact in terms of reducing seasonality. In the four years to 2011, JetBlue’s PRASM in its four traditional shoulder months (January, May, September and October) was up in the 36-45% range, compared to 25-32% growth seen in the other eight months.

Also, as JetBlue slows growth, it is seeing the benefits of having most markets in the “mature” phase, which equates better profitability. In 2012, 86% of JetBlue’s ASMs are in markets where it has been for three years or more, compared to 55% in 2007. And only 5% of its ASMs are now in “new” markets (less than one year), compared to 17% in 2007.

Profit margins especially from the Boston operations should start to accelerate now that the initial business markets are entering years two or three. Chief commercial officer Robin Hayes predicted: “I think we’ll look back [at Boston] and say: that was one of the most important strategic moves that JetBlue ever made”.

Where next?

JetBlue’s management sees considerable further potential to expand in Boston, in terms of adding more Caribbean points and large business markets that customers have asked for. The airline is looking to grow from the 100 or so daily flights it will operate there this summer to 150 flights a day by mid-2015, which would make Boston almost as big as the JFK home base, which currently has about 160 flights a day.

However, the executives stressed that New York remains JetBlue’s core and that it will find ways to grow there. JetBlue serves all New York area airports and was recently pleased to be able to pick up additional slots at LGA. JetBlue’s dominant position and state-of-the-art terminal at JFK, as well as its strong brand, leisure franchise and conscious decision not to go after business traffic in New York, all mean that it is unlikely to be affected by Delta’s aggressive service build-up at LGA this year and the ensuing legacy market share battles in the New York area.

JetBlue has also proved that it can continue to prune its network where necessary. Most recently, as it expands service from Washington DCA, it has decided to significantly downsize Washington Dulles.

On the Latin America side, JetBlue still sees significant opportunities on the northern rim of South America and in Central America. The airline will begin serving Bogotá (Colombia) from Ft. Lauderdale in May, to supplement its successful Orlando-Bogotá route.

In the Caribbean, there are major growth opportunities in the Puerto Rico market, where JetBlue is now the largest carrier following American’s 35% contraction last year. JetBlue is likely to designate San Juan as a focus city (similar in status to JFK, Boston, Ft. Lauderdale, Orlando and the LA basin).

On the question of where the next Boston might be, JetBlue executives stressed that they are “not looking to make an investment in a new Boston market anytime soon”. However, JetBlue will be on the lookout for any interesting opportunities that may unfold as a result of further industry consolidation or right-sizing.

Unusual alliance strategy

The management described airline partnerships as “another area of explosive growth for us”. In the past two years or so JetBlue has expanded the original roster of three, made up of regional carrier Cape Air, Aer Lingus and Lufthansa (also its largest shareholder), to include American, South African Airways, El Al, Emirates, LAN, Virgin Atlantic, TAM, Qatar Airways, SIA, Jet Airways, Icelandair, JAL, Hawaiian and Korean (the latter three were announced in January-February). JetBlue has said that it could announce another 2-4 partnerships in 2012.

JetBlue’s strategy is somewhat unusual in that these are mainly interline agreements, which are so common that airlines do not usually announce them or describe them as alliances. But JetBlue looks at interline as “first base”, and a couple of the relationships have progressed to “second-base”, which is typically one-way codeshares (other carriers placing their codes on JetBlue flights).

JetBlue executives indicated that they are very interested in building more of the interline partnerships into one-way codeshares. However, although the technology is in place for full codesharing, they are hesitant to take that step for fear of it creating additional complexity (having to train airport workers, maybe set up dedicated teams, disclosure requirements, potential for fines, etc.). JetBlue is not ruling it out but currently is not convinced of the benefits of full codesharing.

But it is the results that matter. JetBlue feels that it is benefiting significantly from the existing deals, which now connect customers at eight airports (though JFK still accounts for most of it). In addition to providing incremental customers, some of the partnerships have complementary traffic profiles and help balance JetBlue’s off-peak travel periods.

Some analysts have suggested that JetBlue could gain significantly from American’s plans to expand codesharing (if ever implemented) and have even speculated about closer ties between the two companies. But, as JetBlue’s management again indicated, JetBlue clearly has the most to gain from the “open architecture” strategy that allows it to freely partner with multiple airlines, whoever can feed its network.