JetBlue: Primed for profitable growth and alliance opportunities

March 2011

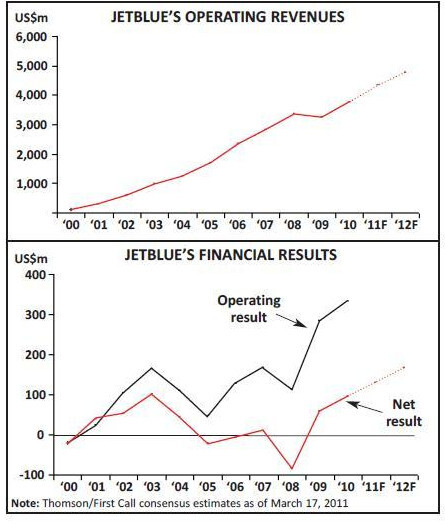

In the US, no carrier currently looks more appealing than JetBlue Airways, New York’s hometown airline that sailed through the recession, earned a healthy 8.8% operating margin in 2010 and has more profitable growth and international partnerships lined up for 2011.

JetBlue, now the sixth largest US carrier in terms of RPKs, has had its share of minor hassles in recent months. It has been a difficult winter in the Northeast, with several snowstorms disrupting operations and crimping revenue generation.

More seriously, higher fuel prices are now hampering the airline’s progress to what analysts had hoped would be double–digit operating margins in 2011.

But it is hard to think of another airline that has deployed smarter strategies and been more creative in recent years. As a result, JetBlue should perform well even in a higher fuel cost environment and looks uniquely well positioned for the longer term.

JetBlue has to be commended, first of all, for its smart network moves. It has found two fantastic new growth markets to complement its original strong niche in New York: the Caribbean and Boston. As a result, it was able to diversify away from the fiercely competitive transcon market and grow profitably through the recession.

Second, while JetBlue has always been able to attract and retain business traffic, it has made further significant inroads into that segment in the past year, thanks to strategies such as massive network and flight frequency expansion in Boston, schedule optimisation, transitioning to Sabre, FFP revamp and new products targeting the business customer.

Third, JetBlue has not lost its traditional cost advantage. It remains one of the most efficient and lowest–cost LCCs in the US.

Fourth, JetBlue has cleverly taken advantage of its leading domestic market position and extensive slot holdings at New York JFK, as well as its strong brand and high service quality, to forge partnerships with multiple international carriers, thus expanding its reach to 300–plus destinations on six continents.

Fifth, JetBlue acted quickly to curtail capacity growth in 2008 and has brought capital spending to relatively modest levels through aircraft sales and order deferrals. The financial community is reassured by what Fitch recently described as the management’s “proven ability to defer aircraft capital spending during periods of weak cash flow”.

First decade: not all plain sailing

Its continued strong revenue momentum, promising further growth opportunities and solid track record are reasons why JetBlue can get away with planned ASM growth as brisk as 7–9% in 2011 without too many complaints from analysts. Now in its 12th year of operation, JetBlue had perfect credentials when it commenced operations from New York JFK in February 2000: ample start–up funds, a strong management team and a promising growth niche. The carrier quickly attained Southwest’s efficiency levels and achieved spectacular 17% operating margins in 2002 and 2003. With its new A320 fleet, state–of–the–art technology and superior in–flight product, JetBlue set new standards in airline service quality in the US and attracted considerable customer loyalty.

It also grew extremely rapidly, achieving “major carrier” status (with $1bn–plus annual revenues) in its fifth year. But JetBlue then stumbled financially, seeing its operating margin plummet to the low single–digits and net results turn negative in 2005 and 2006. The airline was struck by a host of negative factors, including higher fuel prices, a weakened domestic revenue environment, an over–simplified pricing model and an over–aggressive growth plan. Furthermore, an operational meltdown in February 2007 highlighted serious shortcomings in its ability to deal with operational issues.

JetBlue tackled its problems with great gusto, spending two years restructuring and refining its strategy. It drastically slowed growth through fleet reductions, improved revenue generation through a multitude of initiatives and enhanced profitability through network changes.

The February 2007 crisis also led to a leadership change, with president Dave Barger taking over as CEO from the visionary founder David Neeleman. In the subsequent two years the remaining slate of top officers also changed; while most were internal promotions, the August 2008 appointment of ex–BA executive Robin Hayes as chief commercial officer to provide the “global point of view” was an interesting development.

As a result, JetBlue returned to “mainstream” operating margins in 2007 and 2008 (6% and 3.3%, respectively). This was followed by an excellent 8.7% operating margin in 2009, when its legacy peers were hit hard by the global recession. In 2010, despite challenges associated with the Sabre transition and JFK runway work, JetBlue achieved an 8.8% operating margin and a $97m net profit on $3.8bn revenues.

JetBlue’s fortunes in 2011 are likely to be driven by two conflicting trends: its continued strong revenue momentum, and escalated cost challenges, especially higher fuel prices.

JetBlue recorded robust 14.8% revenue growth last year, even though it did not suffer much in 2009 (when its revenues dipped by only 3%). In recent months it has been outperforming the industry in terms of RASM, which is expected to be up by 14–16% in the first quarter, reflecting its growing mix of business customers, as well as continued strong demand in the US domestic and Caribbean markets. The airline is benefiting from competitors’ capacity reductions in some of its core markets. It has been participating in industry–wide domestic fare increases and recently also implemented a $45 one–way fuel surcharge in its Caribbean markets – measures that have helped offset some of the fuel price impact.

Ancillary revenues, which in 2010 amounted to about $20 per passenger (compared to JetBlue’s average fare of $141), are expected to grow by 20% this year. It will mainly reflect further product enhancements; currently JetBlue has no intention of introducing “first bag” fees (a lever that it can always pull if fuel prices continue climbing).

On the cost side, JetBlue does have fuel hedges in place to cover around 32% of its anticipated 2011 needs at prices similar to the current levels. Nevertheless, as an LCC it remains more exposed to fuel than the legacies (because it carries more price–sensitive leisure traffic and because fuel constitutes a larger percentage of its costs). Concerns about fuel prices are the main reason why most analysts currently have a “hold” recommendation on the stock (though some also worry about the growth rate).

Otherwise, JetBlue is committed to maintaining a competitive cost structure.

Its ex–fuel CASM of 6.71 cents in 2010 was among the lowest in the US, thanks to its new and efficient fleet (average age 5.4 years), high aircraft utilisation (11.6 hours daily in 2010), low distribution costs and productive non–unionised workforce.

There are significant cost pressures, particularly in the pay and benefits and maintenance categories, but some of those will ease up in the second half of 2011.

Maintenance costs pressures will continue because to the gradual ageing of the fleet. Despite the fuel outlook, JetBlue is expected to achieve healthy earnings growth in the next two years. The current consensus estimate is EPS of 38 cents in 2011 (up from last year’s 31 cents) and 49 cents in 2012. However, after two years of generating free cash flow (operating cash flow less capex), including $225m in 2010, JetBlue is now unlikely to achieve that goal this year.

Tapping the higher-yield segment

JetBlue has always been well–positioned to attract business traffic because of its unique value proposition, strong brand and great customer service. The basic value proposition is that “competitive fares and quality air travel need not be mutually exclusive”.

However, like Southwest, JetBlue realised five or six years ago that it needed to do more – namely upgrade systems, revamp revenue management and introduce specific products — in order to effectively tap the higher–yield segment. The result was increased flexibility in yield management and revenue generation and initiatives such as “Even More Legroom” (“EML”, a new “front cabin” product introduced on the A320s in March 2008 that now costs up to $65), offering refundable fares and listing fares in all four major GDSs.

EML, which offers a generous 38–inch pitch in the front rows of aircraft (four inches more than in other rows) generated over $85m in revenue in 2010. In September JetBlue began offering early boarding for EML customers – apparently also well received. Upcoming enhancements include a “priority security” offering at selected airports this spring.

The airline believes that it offers “the best coach product in the markets it serves with a strong core product and reasonably priced optional upgrades”. It is not interested in “nickel and diming” customers and even offers free DirecTV and XM Satellite radio.

Just over year ago JetBlue switched to a new reservations and customer service system, which has increased its capabilities to grow the current business, add more commercial partnerships and attract more business traffic. As a result of the transition to Sabre, business travellers can now benefit from real–time connectivity in the GDS channel. This and other new provisions, including the availability of more refundable fare types, have helped improve corporate travel penetration. While business traffic has traditionally been a steady 15–20% of JetBlue’s total passengers, now the airline is talking about it being somewhere “north of 20%”.

JetBlue’s enthusiastic participation in the four main GDSs (Sabre, Galileo, Worldspan and Amadeus) and the four major online travel agents is in interesting contrast with American’s and other legacies’ recent attempts to pull out of some of those channels because they impede their ability to unbundle products and achieve the lowest distribution costs.

When quizzed recently about this by analysts, JetBlue’s Robin Hayes noted that bookings through the GDSs are a small slice of the pie and that most of JetBlue’s sales continue to be through its own web–site, which is by far its lowest–cost distribution channel. The GDS channels help JetBlue break into the corporate market, and the strong yield premiums more than cover the increased distribution costs. However, regarding online travel agents, the jury is still out at JetBlue on how many of those bookings are truly incremental.

Disciplined, focused growth

JetBlue’s ASMs are expected to be up by only 1–3% in the current quarter because of some pilot training issues, but growth is due to accelerate sharply by the summer and amount to 7–9% in 2011 – well ahead of the industry rate. CEO Dave Barger said at the JP Morgan transportation conference on March 22 that he “feels good about the capacity plans in light of what is happening in our revenue environment”. Of course, JetBlue will be keeping a close eye on fuel prices and market conditions and is prepared to revise plans if necessary.

JetBlue can get away with that kind of growth, in the first place, because it has profitable growth opportunities. Its expansion will again focus on Boston and the Caribbean – proven markets where it is also benefiting from competitors’ capacity reductions. American has shifted capacity particularly from Boston and San Juan to its cornerstone markets. And last year JetBlue was able to grow its capacity by 6.7% — virtually all of it in Boston and the Caribbean — while still achieving 7.6% RASM growth.

Also, JetBlue has demonstrated repeatedly in the past five years its ability to manage growth and capital spending. It reduced its ASM growth from an annual average of 25% in 2003–2006 (when it was one of the fastest growing US LCCs) to 12% in 2007, 1.7% in 2008 and 0.4% in 2009.

Last year JetBlue continued to defer near–term A320 and E190 deliveries to reduce capex and smooth out the delivery schedule. The 40% reduction in Airbus deliveries in 2012–2013 meant a $500m reduction in aircraft purchase obligations through 2013. The management noted that “lowering capex is a key component of our goal to grow on a sustainable basis and consistently generate positive free cash flow.”

This year JetBlue is scheduled to receive only four A320s and five E190s, and its aircraft capex will be only $390m, contrasting with the $1.1–1.3bn it spent annually in 2005–2006. However, to facilitate this year’s growth, JetBlue has taken six A320s on six–year operating leases from GECAS.

Of course, JetBlue retains a significant aircraft order book that will facilitate growth in the longer term. At year–end 2010, when its operating fleet totalled 160 (115 A320s and 45 E190s), it had 109 aircraft on firm order – 55 A320s for delivery through 2016 and 54 E190s for delivery through 2018 – plus options for eight A320s (2014–2015) and 65 E190s (2012–2018).

That said, JetBlue has continued to work with the manufacturers to reduce capex in the later years. Although it now has only seven A320s arriving in each of 2012 and 2013, the Airbus deliveries currently pick up sharply in 2014 (12, followed by 15 in 2015 and 10 in 2016), while the E190s will be arriving at a rate of 7–8 each year through 2018.

JetBlue is focused on maintaining a strong balance sheet. It is highly leveraged but has manageable debt maturities and ample unrestricted cash reserves (around 25% of trailing 12–month revenues – a level it also intends to have at the end of 2011).

Network and alliance plans

JetBlue’s current 64–point network covers 21 states, Puerto Rico and 11 countries in the Caribbean and Latin America. The 65th and 66th new cities, Anchorage (Alaska) and Martha’s Vineyard (Massachusetts) will be added on a seasonal basis in May. While 55% of its daily flights are to or from the New York City area, the airline has also developed Boston, Ft. Lauderdale, Orlando and LosAngeles/Long Beach as focus cities.

The most notable recent addition was Washington Reagan National in November – possible because JetBlue was able to acquire coveted slots there through a swap with American. The strategy in Washington DC is the same as in the other large metropolitan areas: to serve all the airports (National, Dulles and Baltimore/Washington) and to quickly acquire a leading position in key markets (JetBlue immediately became the largest carrier in the Boston–Baltimore/Washington market, with 18 daily flights).

But otherwise in the past couple of years JetBlue’s efforts have focused on two areas: expanding its Caribbean network and building a formidable market position in Boston.

The Caribbean, which JetBlue has called “a natural out of New York” and where it added its 16th destination (Providenciales in the Turks & Caicos Islands) in February, has been a brilliant move for the carrier. The markets have year–round demand, have matured quickly, generally require minimal up–front capital, generate higher revenue than domestic flights of comparable distance and, in spite of limited daily frequencies, are relatively low cost.

Those markets saw strong RASM improvements even during the recession (many have high volumes of VFR traffic, which tends to be more recession–resistant) and despite significant capacity addition.

In fact, Caribbean operations accounted for all of JetBlue’s revenue growth in the past two years; between 2008 and 2010, revenues in those markets expanded from $511m to $879m, while the airline’s domestic revenues remained unchanged at $2.9bn. And those markets continue to outperform: in the fourth quarter, Caribbean/Latin America recorded the strongest RASM growth in the airline’s network.

Growth in that region has also helped JetBlue achieve a more balanced network. In the past five years, East–West’s share of ASMs has declined from 55.1% to 34.5%, while Caribbean’s share has surged from 6.4% to 23.2%. By the end of this year JetBlue expects 25% of its ASMs to be in the Caribbean/Latin America region.

JetBlue is now the largest carrier in terms of ASMs in the Dominican Republic, having added its fourth destination there (Punta Cana) last year. This summer it also expects to be the largest carrier in Puerto Rico, where it plans to boost departures by 30% with new services from San Juan to Jacksonville and Tampa in May. The airline’s summer schedule will have over 30 daily flights from three airports in Puerto Rico to five mainland cities and intra- Caribbean to Santo Domingo.

JetBlue has been in Puerto Rico since 2002 and has expanded steadily, but it can now take advantage of American’s planned 35% contraction in San Juan in the second quarter. San Juan has been a strong market and JetBlue planned to grow there anyway, but American’s moves have certainly helped speed things up.

JetBlue still sees plenty of growth opportunities in the Caribbean and Latin America that it can tap into. Of course, it is not the only LCC growing in the Caribbean.

The region has been a major focus for the likes of WestJet and Spirit, as well as AirTran, which will be an even more formidable competitor if Southwest’s plans to acquire it go through.

The other area where JetBlue has been capitalising on gaps left by competitors is Boston. Last year the airline grew its daily departures there by 30% and added six new destinations. JetBlue is already the city’s leading carrier in terms of departures and destinations served. This year will see another 30%-plus increase in Boston departures to around 100 per day. New services to Newark, Portland and the DominicanRepublic will increase JetBlue’s nonstop destinations from Logan to 42 — more than double the next largest carrier’s.

What makes Boston extra special for JetBlue is the opportunity to capture significant business traffic share, including corporate contracts. There are many obvious reasons: the network that already spans the nation and the Caribbean, the large number of destinations served, the high frequencies offered in key business markets, attractive schedules, availability of more refundable fares, real–time connectivity to the GDSs, EML priority boarding, the revamped FFP, etc. But it also seems that JetBlue and Boston are simply a really good fit. All aspects of the airline’s service and strategy, including the brand, product, aircraft–mix and style, are just ideally suited to the Boston market.

In the past five years, JetBlue’s share of Boston seats has increased from 10% to around 22%, while American’s share has fallen from 17% to 11%, US Airways’ from 16% to 14% and Delta’s from 18% to 17%.

In the fourth quarter, competitive capacity in Boston was down about 2.5%.

Of course, JetBlue’s greatest strength is its dominant position in New York, the nation’s largest air travel market. The airline intends to continue to leverage its presence at JFK, where its operations account for more than 40% of the airport’s domestic passengers and where it moved to its new 26–gate, state–of–the–art Terminal 5 in October 2008.

The JFK base makes JetBlue perfectly positioned to develop partnerships with international carriers. The past year or so has seen much progress on that front as JetBlue has expanded the original roster of three, made up of regional carrier Cape Air, Aer Lingus and Lufthansa (also its largest shareholder), to include American, South African Airways, El Al, Emirates, LAN and Virgin Atlantic (the latter was announced on March 22). JetBlue has said that it could announce another 5–6 partnerships in 2011.

The aim is to connect customers into the core focus city markets. Most of the partnerships connect at JFK and Boston, but SAA and Virgin also connect with JetBlue at Washington Dulles, and Virgin is a much–appreciated first partner at Orlando (which it serves with up to five daily flights from three UK airports).

JetBlue has indicated that it hopes to secure a partner at Los Angeles.

JetBlue’s strategy is somewhat unusual in that these are primarily interline agreements, which are so common that airlines do not usually announce them or describe them as alliances. The deals merely allow passengers to book flights involving two airlines on a single ticket; they are not incremental to the earnings power of the airlines. So why announce them? Or, as one analyst asked at the JP Morgan event, are the interline relationships like “getting to first base”?

JetBlue executives explained that interline is indeed looked at as “first base”, though only some of the relationships progress to “second base”, which is typically one–way code–shares (foreign carriers placing their codes on JetBlue flights; currently with Lufthansa and SAA) or reciprocal FFPs (American). The technology is apparently in place for full code–sharing, but JetBlue executives indicated last year that they wanted to proceed thoughtfully and for now preferred the less complex interline deals.

JetBlue began interline sales on its web site only this year and currently only covers Cape Air, Aer Lingus and American. Like other LCCs such as GOL and WestJet, JetBlue looks at alliances a bit differently.

Since it does not operate globally, it does not need feed at distant locations and therefore does not need to be part of a global alliance. It clearly has the most to gain from the “open architecture” strategy that allows it to freely partner with multiple airlines, whoever can feed its network.

Some eyebrows have been raised at the link with Virgin Atlantic, as JetBlue competes fiercely with Virgin America particularly for transcon traffic. But JetBlue executives point out that those two are different entities, in different geographies. In any case, one of JetBlue’s most important partners (American) is also one of its key competitors.

| 2010 | 2008 | 2005 | |||

| E. Coast - W. Coast | 34.5% | 41.5% | 55.1% | ||

| Northeast - Florida | 31.4% | 33.9% | 33.5% | ||

| Medium-haul | 3.3% | 3.0% | 1.1% | ||

| Short-haul | 7.6% | 7.6% | 6.6% | ||

| Caribbean (Incl. Puerto Rico) | 23.2% | 14.0% | 6.4% | ||