North Atlantic: the metal neutral market

March 2011

This summer three airlines will carry at least 73% of air traffic across the Atlantic. They are: International Airline Group (BA merged with Iberia) and virtually merged with American; United (incorporating Continental) virtually merged with Lufthansa and Air Canada; and Air France/KLM virtually merged with Delta (incorporating Northwest).

These airline groupings represent the deeply integrated joint ventures at the core of the three Branded Global Alliances (BGAs – oneworld, Star and SkyTeam). On a slightly broader measure, including all alliance members, the proportion of the North Atlantic controlled by the alliances is 85%.

The term “virtual merger” is now more than marketing hype, it is becoming a legal necessity mandated by the US DoT in order for the US and European carriers to cooperate as closely as possible without actually merging, which would be impossible because of nationality requirements, and this cooperation has to take the form of “metal neutrality”. Metal neutrality is described by the DoT (which has the authority to issue immunity and regulate alliances) as a JV in which the airlines “become effectively indifferent to which plane or ‘metal’ carries a passenger ... this form of cooperation is a close substitute to a merger because it typically involves full coordination of the major airline functions on the affected routes, including scheduling, pricing, revenue management, marketing and sales”.

This situation may appear odd: the US authorities normally set out to make companies compete not collude, and regularly punish erring executives with gaol time. The logic is linked into the evolution of Anti Trust Immunity (ATI) through which the US authorities allow airlines in a JV to discuss and set fares, schedules, etc. ATI has been used as an incentive to advancing the policy aim of greater international liberalisation, first awarded in 1993 to KLM and Northwest following the first Open Skies agreement between the Netherlands and the US. KLM and Northwest, with their dual hub system, achieved metal neutrality but other immunised alliances like that between Lufthansa and United did not initially take their cooperation that far. ATI was granted back in 1996.

Former KLM General Counsel and the world’s leading expert on metal neutrality Paul Mifsud explained in the November 2010 edition of the Airneth newsletter how the DoT’s position has crystallised into almost obligatory metal neutral conditions following an initial disapproval for ATI for all four main carriers linked by the 2005 merger of Air France and KLM; in approving the re–submitted plan, the DoT stated:

“…the Joint Applicants now supply a detailed joint venture agreement that integrates international operations to such an extent as to suggest metal neutrality and seamless travel across one joint network. The proposed alliance is likely to result in the introduction of new capacity and greater availability of discount fares across the entire joint network – benefits that we tentatively find to be substantial in the circumstances of this case. Building on the highly integrated common bottom line arrangement in the Northwest/ KLM alliance, the four–way JV represents a significant shift in the way in which SkyTeam plans to deliver benefits to the travelling and shipping public.”

Since that case, it appears that a metal neutral joint venture has become a DoT requirement for a grant of ATI. The DOT has conditioned subsequent ATI approvals with the specific requirement that the major participants in both the Star Alliance and oneworld parties enter into a metal neutral joint venture within 18 months of approval.

Double marginalisation arguments

Why does the DoT (and the EU Commission, by association) place such importance on metal neutrality? One of the key criteria for the DoT is that the immunised JVs should bring public benefits.

These can include greater route choice, better scheduling, sharing of FFPs and – in particular – a reduction in fares, which is surprising. In anticipating fare reductions the DoT has relied heavily on the work of Jan Brueckner, an academic who has analysed the impact of alliances on interline fares, using the theory of double marginalisation. Basically this states that the more integrated an alliance, the less incentive the participating airlines will have to maximise fares on their legs of a connecting flight, hence the integrated fare will fall.

In his latest analysis (October 2010) Brueckner estimated that the impact of a code–share on a transatlantic interline fare is to reduce it on average by 3.9%, an alliance agreement reduces the fare by a further 7.6% and a fully immunised JV takes off another 4.4% — so in total interline fares would benefit to the tune of 15.9% due to the introduction of immunised JVs. A fully merged transatlantic airline would produce fare savings of 18.9% compared to the base interline fare.

Merge without merging

So, the theory goes, in order to capture these benefits airlines in an immunised JV should get as close as they can to being a merged entity without actually merging – and this means metal neutrality.

(In practice, selling the concept to passengers is challenging, given the difference in hard and soft product spec between alliance members; moreover, within the alliances the mechanisms for precisely allocating revenues and costs in a metal neutral fashion must be subject to intra–alliance competition and/or conflicts of interest.)

Importantly, the US DoJ contests the DoT findings on the interline fare benefits, and concentrates on the impact on point–to–point fares. Hubert Horan, a leading US analyst, and contributor to Aviation Strategy, has described the double marginalisation theory as consumer fraud, part of a malign policy to recreate old–style IATA–type cartels.

Whether one ascribes to the anticompetitive view or regards the alliance building as representing an overdue rationalisation of the intercontinental markets, the degree of consolidation on the North Atlantic is now advanced.

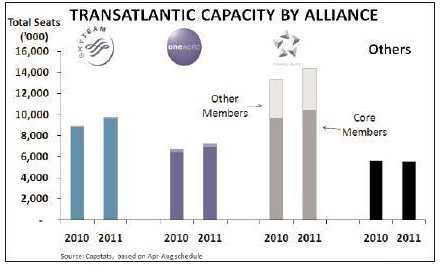

At the highest level the North Atlantic market splits out into four airline groupings: oneworld with 20%, Star with 39%, SkyTeam with 26% and others with 15% — which looks like a competitive oligopoly. (‘Others’ is mostly Virgin Atlantic, which has spent the last six months looking for an alliance intro – see Aviation Strategy, Jan/Feb 2011).

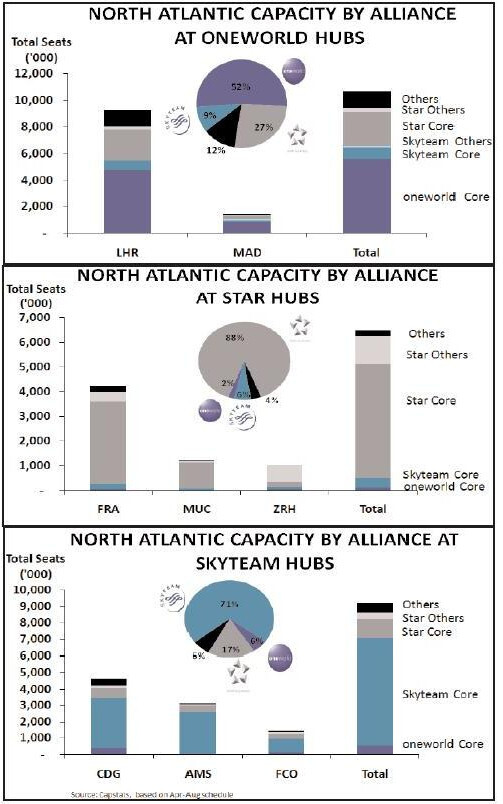

Looking at the North Atlantic from a European hub perspective: from the oneworld hubs, London Heathrow (and Madrid, which doesn’t add much in the North Atlantic region), oneworld airlines account for 52% of capacity. For the Star hub system, the most fully integrated alliance operation, encompassing Frankfurt, Munich and Zurich airports, the Star airlines’ share is a totally dominant 88%. For SkyTeam, with its dual hubs at Paris CDG and Amsterdam, the market share is 71%. Take the analysis to a further level of granularity: on the Euro–hub to New York routes Star is overwhelmingly dominant from its base, SkyTeam is dominant from CDG and Amsterdam; oneworld takes more than half the market but does face significant competition. On hub–to routes 100% control is the norm.

This degree of consolidation should logically increase the average fares achieved, and indeed this is what the latest transatlantic financial results indicate.

Atlantic numbers from the three major US airlines (of the European carriers, only BA has ever split out its Atlantic division but a couple of years ago stopped revealing this detail) are probably indicative of the positive impact of the consolidation on financial results, even allowing for the rebound from the 2009 depression.

In 2010 United’s Atlantic unit revenue (PRASM – Passenger Revenue per ASM) was up 21%, compared to system–wide 19%; Delta’s Atlantic unit revenue was up 21%, compared to system–wide 13%; American’s was up 16% compared to system–wide 10%. (In all cases Pacific PRASM growth, where consolidation has also accelerated, was higher, 38% for United, 26% for Delta and 16% for American.)

| oneworld | Star | SkyTeam | Others | Total | ||||||

| LHR-NYC | 51% | 15% | 10% | 25% | 100% | |||||

| CDG-NYC | 14% | 15% | 66% | 5% | 100% | |||||

| AMS-NYC | 0% | 27% | 73% | 0% | 100% | |||||

| FRA-NYC | 0% | 92% | 8% | 0% | 100% | |||||

| MUC-NYC | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | |||||

| Note: New York = JFK and EWR | ||||||||||

| oneworld | Star | SkyTeam | Others | Total | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LHR-DFW | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| LHR-ORD | 62% | 33% | 0% | 6% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CDG-ATL | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CDG-DTW | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| AMS-ATL | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| AMS-DTW | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| FRA-CHI | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| FRA-HOU | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||