US LCCs: When will they resume growth?

March 2010

Investor interest in the US is currently intensely focused on the legacy airline sector, which is likely to see the strongest improvement in revenue and earnings as economic recovery gathers pace. But US low–cost carriers also deserve attention because of their remarkable capacity discipline, strong profit performance in 2009 and arguably better long–term prospects.

The leading LCCs outperformed the legacy carriers financially through the recession. Some of the LCCs switched quickly from aggressive growth to a no growth mode. They found profitable new markets, reduced dependence on their traditional bases and tapped new ancillary revenue sources. They improved revenue management and invested heavily in new technology, which will enable them to fully develop ancillary revenues and code–share internationally. And, of course, they emerged from the recession with exceptionally healthy cash balances.

As a result, there is now a very interesting confluence of a group of strong LCCs, a massive domestic contraction by the legacy carriers (which many feel is permanent) and a budding economic recovery.

Gradually increasing

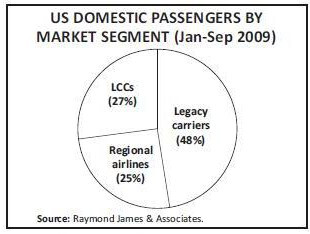

Raymond James’s optimistically titled “Growth Airline Conference”, held on February 4th in New York (actually an annual event and always called that), shed much useful light on the leading LCCs’ post–recession growth strategies. When will they start growing again and where will they go? market share Back in 2004 it was widely predicted that the LCCs’ then–25% passenger share would grow to 40% or more within five years (see Aviation Strategy, June 2004). That has not happened. In fact, the LCCs have not seen their aggregate market share change very much at all since 2004. According to Raymond James’s late- January “2010 Growth Airline Outlook” report (published in conjunction with the conference), the LCCs grew their share of domestic passengers by only two percentage points between 2003 and 2007, from 25% to 27%. The share dipped to 25% in 2008, before recovering back to 27% in January–September 2009.

The predictions did not materialise because of structural changes in the industry, as well as some notable exits from the LCC sector. The surviving LCCs, especially the leading ones — Southwest, JetBlue and AirTran — have all steadily increased their market shares.

The legacy carriers’ domestic mainline operations have contracted sharply in the post–2001 period, but most of that capacity has been passed to regional partners. Since 2003, while the legacies’ domestic passenger share has fallen from 57% to 48%, regional carriers’ share has surged from 18% to 25%. This was another example of how the legacy sector really got its act together in the post–2001 days, in many cases with the help of Chapter 11.

The biggest change in the LCC sector has been the exit of America West, following its merger and integration with US Airways.

The US LCC sector has seen its share of turmoil due to the past two years’ economic challenges. Of the two significant new entrants that began operations in 2007, one is still here (Virgin America) but the other has disappeared (Skybus). Of the two established LCCs that went into Chapter 11 in 2008, one has been revived (Frontier) but the other was liquidated (ATA).

ATA, Frontier and Skybus succumbed to the slowing economy and mini–credit crisis that hit the industry in the spring of 2008.

ATA shut down after losing a key military contract (it was an oddball among LCCs in that it depended heavily on charters). Skybus, which had tried to test a Ryanairstyle business model in the US after raising a record $160m in start–up capital, failed due to a host of reasons, including Columbus being too small to support a low–cost carrier hub.

Denver–based Frontier, which was forced into bankruptcy by credit card processor demands, emerged from a successful Chapter 11 restructuring in October 2009 as a wholly owned subsidiary of Republic Airways Holdings, the parent company for several regional carriers. Republic bought Frontier for $109m plus debt assumption of $330m via an auction process last summer, after Southwest withdrew its bid after failing to secure approval from its unions.

Frontier is now a new type of LCC model in the making. It has retained its brand, identity, fleet and markets, but its back–office functions are being consolidated with those of Milwaukee–based niche operator Midwest Airlines (another recent Republic acquisition). The acquisitions stemmed from Republic’s desire to diversify away from the regional sector, where growth prospects are still very uncertain.

Instead of trying to morph into an LCC (a task where others have failed), Republic opted to buy two established airlines with strong brands and loyal customer bases and drive additional operational and cost efficiencies from the combined operations.

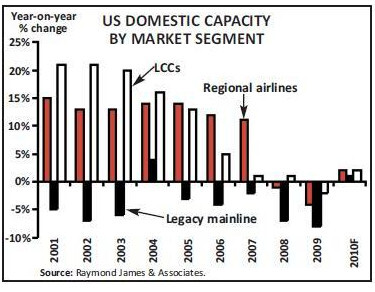

This downturn saw the first–ever aggregate capacity reduction by the US LCCs. After growing at double–digit annual rates up to and including 2007, the LCC sector cut capacity by 1% in 2008 and 4% in 2009. This was instrumental in creating a rational pricing environment because, even with a 25–27% market share (or a 22% revenue share), the US LCCs have controlled pricing in the domestic market since the early part of the last decade.

Last year all three of the main domestic segments saw capacity declines. However, because the legacies cut so much deeper (8% mainline), and with regional capacity being curtailed by 2%, the LCCs gained market share. Southwest’s CEO Gary Kelly estimated at the conference that the airline’s share of the domestic market rose by “at least 1%” in 2009, worth $800m on an annualised basis.

Prospering through recession

Right across the spectrum, the US LCCs appeared to be profitable last year. The four listed LCCs outperformed their legacy counterparts in terms of revenues, RASM and profit margins. Allegiant had an operating margin of 21.9%, JetBlue 8.5%, AirTran 7.4% and Southwest 5.2% in 2009.

Frontier was earning lofty 8%-15% pretax margins last summer, when it was still in bankruptcy, and is believed to have posted a profit for 2009. Even Virgin America, which has run up substantial losses since its launch in 2007, recently reported its first quarterly operating profit, a modest $5.1m on revenues of $157.9m for the September quarter.

Furthermore, Southwest is now leading the industry out of recession with a spectacular traffic and revenue momentum. The airline’s PRASM surged by 14- 15% in January. Passenger traffic rose by almost 9% despite a 7% capacity reduction. And Southwest is not discounting heavily.

The 2009 profits were all the more gratifying because each of the top three LCCs had some issues in the preceding years. Southwest’s main challenges were its waning fuel hedges and cost pressures generally, which caused it to report its first quarterly net losses in 17 years in 2008. JetBlue and AirTran had a multitude of issues in the mid–2000s, including over–aggressive growth, and were hit hard by the fuel price hikes. JetBlue had net losses in 2005, 2006 and 2008. AirTran had many years of marginal or fluctuating profits and a sizeable loss in 2008. Periodically there were concerns about both airlines’ cash positions, and in late 2007 JetBlue even resorted to selling a 19% ownership stake to Lufthansa for $300m.

Probably the single most important factor that helped the top three LCCs back to solid profitability was that they all acted early to bring capacity growth to a halt. And they did it properly by cancelling or deferring aircraft orders or retiring older aircraft.

However, the LCCs were still able to undertake new expansion. In other words, they redeployed capacity from weak parts of their networks to promising new markets. Examples were Southwest’s venture into four major new cities in 2009 and JetBlue’s continued Caribbean expansion.

Of course, the LCCs weathered the recession well because their primary focus is on leisure traffic. But there was also much anecdotal evidence of business travellers trading down from the legacies to the LCCs – a phenomenon aided by the fact that in many cases US LCCs provide a higher quality product and better service than the legacies.

The airlines have showed considerable restraint on the pricing front (helped by the capacity cuts). They also now have better yield management systems and have aggressively tapped new ancillary revenue sources.

Southwest lessons

According to the Raymond James report, Southwest, JetBlue, AirTran and Allegiant escaped with a mere 8% aggregate decline in passenger revenue in the first three quarters of 2009, compared with a 21% decline for the domestic industry (ATA mainline). The fact that the LCCs now participate in both the leisure and business markets means that they too should benefit from economic recovery. Southwest was able to turn in a respectable $143m net profit before special items for 2009 (its 37th consecutive profitable year), in the first place, because of capacity restraint. After long growing at a brisk 8–10% annual rate, the airline began to slow growth in 2007, grew by only 3.6% in 2008 and contracted by 5.1% in 2009. The wind–down has been achieved through 737–700 order deferrals and accelerated retirement of older 737s.

Second, Southwest is seeing the fruits of a major three–year remodelling effort launched in June 2007, which was aimed at adapting to a higher fuel–cost environment and increased competition from other LCCs, strengthening the brand and attracting more business traffic. The result has been a growing range of new products, programmes and processes that have brought in significant extra revenues.

Third, Southwest has been extremely aggressive with route optimisation efforts. Last year it eliminated so many unprofitable flights that it was able to add Minneapolis/St. Paul, New York LaGuardia, Boston Logan and Milwaukee to its network, while also cutting overall capacity. The new cities have been strong revenue contributors almost from day one.

JetBlue had a bumper year, generating a $58m net profit (its highest since 2003) and positive free cash flow for the first time in its history. The airline ended the year with industry–leading cash reserves ($1.1bn or 35% of annual revenues).

Capacity discipline has been the key factor behind JetBlue’s strong results in the past two years. The airline reduced its ASM growth from an annual average of 25% in 2003–2006 to 12% in 2007, 1.7% in 2008 and 0.4% in 2009. In the past three years JetBlue has rescheduled almost 100 aircraft and sold 19; it took only nine new aircraft in 2009, compared to the originally scheduled 36.

JetBlue has also been optimising its network. One of its smartest moves has been to switch significant capacity from the fiercely competitive transcontinental market to the Caribbean. The Caribbean markets are strong, have year–round demand and have matured quickly. The VFR/leisure traffic held up well through the recession. By mid–2010 the Caribbean will account for about 25% of JetBlue’s total capacity, up from 12% in 2007, while transcon’s share is now down to 30%. The Boston market has been another success story. JetBlue’s results also benefited from strong ancillary revenue growth.

AirTran had its best year ever in 2009, following a very difficult 2008. The airline earned a $135m net profit (5.8% of revenues), contrasting with a year–earlier $266m loss. The turnaround was attributed, first, to quick action in late 2008 to curtail ASM growth, which had exceeded 20% annually for five years. AirTran deferred or sold 47 aircraft from its 2008- 2011 fleet plan, enabling it to reduce ASM growth to 4.9% in 2008 and to cut capacity by 2.2% last year.

Second, AirTran’s special blend of high quality (a well–established business class for a small extra fee and other perks) and the lowest cost structure in the industry was a good combination to have in a steep recession.

CASM gap still significant

Third, AirTran continued to diversify its network away from Atlanta, expanding in key markets like Baltimore, Milwaukee and Orlando, as well as the Caribbean. Atlanta’s share of AirTran’s ASMs has declined from 91% in 2000 to 47% in 2010. The unit cost gap between the US legacies and LCCs has narrowed in the post- 2001 era, largely because of the impressive cost cuts achieved by the legacies in or out of Chapter 11. However, LCCs still enjoy a significant cost advantage.

An analysis conducted by consulting firm Oliver Wyman for Raymond James found that, on a stage–length and aircraft–size adjusted basis, the average Legacy carrier unit costs are 36% higher than the LCC unit costs.

According to the analysis, which was based on third–quarter 2009 data, LCC unit costs ranged between 6.6 and 9 cents and legacy unit costs between 9.2 and 11.7 cents per ASM (at 1,000 mile stage length). AirTran had a one–point lead as the lowest cost carrier (6.6 cents), while Spirit, a Florida–based privately held LCC, was the second–lowest cost carrier (7.6 cents), followed by Southwest, Allegiant and JetBlue (7.8, 7.9 and 9 cents, respectively).

Frontier was not in those comparisons, but Chapter 11 gave it one of the lowest unit costs in the industry. According to Republic, on a stage–length adjusted basis it has a slight disadvantage to AirTran but a fairly significant advantage to Southwest.

The Oliver Wyman analysis also found that, on a reported basis, the legacy–LCC cost gap narrowed significantly last year. This was attributed to the disappearance of Southwest’s fuel hedge advantage and the greater non–fuel unit cost pressures experienced by LCCs. The latter probably mainly reflected the LCCs’ no–furlough policies. Carriers like Southwest and JetBlue want to protect their brand and culture, which they view as service differentiators in the long run.

Ancillary revenue strategies

Also, many LCCs in the US continue to view themselves as growth companies. Therefore they continue to make investments in the infrastructure necessary for growth. One good example is JetBlue’s switch–over to the Sabre reservation system in the current quarter. While ancillary revenues generally have helped all US airlines, with “unbundling” (charging extra fees for services that were previously included in the air ticket price) there is an interesting contrast between Europe and the US. In Europe, unbundling was pioneered by the leading LCCs like Ryanair, and the Euro–majors are now reluctantly following. In the US, it was the legacies that led the way with unbundling in 2008; the main LCCs have followed, but somewhat hesitantly. (Of course, small niche LCCs like Allegiant, Spirit and now defunct Skybus have long had Ryanair–style strategies.)

The bag fees are a case in point. The legacies introduced fees to cover all checked bags on domestic flights in 2008. Many LCCs followed suit, but JetBlue has not added a first checked bag fee and Southwest has not introduced any bag fees at all.

Being a lone holdout gave Southwest a unique opportunity to differentiate itself, which it did with the help of an advertising campaign called “Bags Fly Free”. While sceptics argued that the airline was just turning away revenue, Southwest believes that the strategy has paid off handsomely, bringing in “hundreds” of millions of extra revenue in 2009.

JetBlue and Southwest have focused on developing ancillary activities that enhance their brands. In the past two years they have especially strived to cater for premium passengers. Southwest’s “Business Select” product, its new boarding method and “EarlyBird” check–in (introduced since late 2007) have brought in significant extra revenues. JetBlue’s “Even More Legroom” front–cabin offering (introduced in March 2008) made a useful $70m revenue contribution in 2009.

Growth plans and outlook

Southwest and JetBlue are in the process of putting in place the technology that will enable them to fully develop ancillary revenues. Southwest is in the middle of a multi–year technology drive that, among other things, will facilitate a new FFP from late 2010 (offering enormous potential) and a new revenue management system from 2011. Sabre will give JetBlue powerful new tools to maximise ancillary revenues. Some analysts have speculated that a first bag fee could be among the initiatives JetBlue will be launching in late 2010, but recent management comments suggest that the airline continues to have serious reservations about such a move. The argument put forward frequently is that since the legacy carriers continue to lose money domestically, they will continue to reduce capacity in the domestic market and will focus on international expansion. The Raymond James report suggested that the US legacies could eventually follow the direction of the top three European flag carriers, which derive only 25% of their capacity from intra- European flying.

This would bode well for the US LCCs in the long term. However, with economic recovery being uncertain and aircraft deliveries remaining modest, 2010 is likely to see extremely limited domestic capacity growth by all industry segments. In Raymond James’ mid–January estimates, legacy, regional and LCC capacity will inch up by 1%, 2% and 2%, respectively, this year. But the analysts did suggest that higher aircraft utilisation could lift LCC capacity growth 6–10% higher this year without any incremental aircraft.

The report estimated that Southwest, JetBlue and AirTran maintain aircraft orders and options that could expand their combined capacity at a 6% CAGR range through 2012.

But what do the airlines think? Southwest currently does intend to grow capacity in 2010 and expects to end the year with the same number of aircraft (537) that it had at year–ends 2008 and 2009. CEO Kelly remarked at the conference: “When we start hitting our profit targets and our return on invested capital targets, I think that will be the time we get serious about growing the airline again”.

JetBlue expansion

But Southwest will still be able to open new cities and grow in strong markets, thanks to its route optimisation efforts. It will start serving the new $318m Panama City Beach (Florida) airport when it opens in May – not a typical Southwest market in that it is completely undeveloped, but the risk will be minimal because a local real estate development company is underwriting the new services. Southwest will also continue to grow in important existing markets like St. Louis and Denver. JetBlue is looking to grow its ASMs by 5–7% this year, but the growth will mainly come from increased aircraft utilisation and will be totally driven by its Boston and Caribbean markets; capacity in the rest of the network will decrease. The plan is to get back to the 2007 utilisation rate on the A320s, which was an industry–leading 12.8 hours daily (last year’s was 11.5 hours).

JetBlue was previously expected not to take additional aircraft in 2010, but a new deal with Embraer in January (which will further smooth the delivery schedule) accelerated the delivery of four E190s to this year. But these aircraft will not be a significant factor in capacity growth.

This year’s plans include adding Punta Cana in the Dominican Republic as the 15th international destination in May, growing Boston departures by 30% and “connecting the dots” between the core cities (New York, Boston and Orlando) and the Caribbean. JetBlue is being helped by legacy carrier contraction in Boston.

CEO Dave Barger suggested recently that an appropriate longer–term growth rate for JetBlue might be 5% annually, with higher rates possible when there are extra opportunities. However, “every route, every aircraft, every new city has to earn its way”. JetBlue’s A320 deliveries currently go up sharply in 2011–2012, but the airline indicated that it could again work with the manufacturers to smooth out the schedule.

Both Southwest and JetBlue will be relying more on code–shares in the future. Southwest expects to have the technology in place by late 2010 to launch the long–awaited code–shares with Canada’s WestJet and Mexico’s Volaris. JetBlue began code–sharing with Lufthansa in November (to complement its code–shares with Aer Lingus); the shift to Sabre will facilitate more airline partnerships in the future.

AirTran expects its ASMs to increase by 3–4% in 2010, largely because a planned sale of two aircraft delivered in the fourth quarter fell through, as well as through increased utilisation. Otherwise AirTran has no aircraft deliveries until March 2011.

One third of this year’s growth will be in Milwaukee and the other two–thirds in Florida and the Caribbean. Milwaukee is AirTran’s latest focus city. Having failed to buy Midwest Airlines there in 2007, AirTran has built up its own service in Milwaukee, which it sees as the third Chicago airport. It is already present in 18 of the top 20 markets. Milwaukee is currently quite a battleground between AirTran, Southwest and Midwest.

For the longer term, AirTran is looking for moderate growth, earning its cost to capital. Aircraft deliveries will resume in 2011, with seven scheduled for that year and eight for 2012, which CEO Bob Fornaro calls a “sensible fleet plan for the new normal”.

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010F | 2011F | |

| AirTran | 87 | 108 | 127 | 137 | 136 | 138 | 138 | 145 |

| Allegiant | na | na | 26 | 35 | 38 | 46 | 52 | 60 |

| JetBlue | 69 | 92 | 119 | 134 | 142 | 151 | 155 | 163 |

| Southwest | 417 | 445 | 481 | 520 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 547 |

| Total | 573 | 645 | 753 | 826 | 853 | 872 | 882 | 915 |

| Growth | 11% | 13% | 13% | 9% | 3% | 2% | 1% | 4% |