A regional future for CSA Czech Airlines?

March 2010

Following CSA Czech Airlines’ disastrous attempt at privatisation in 2009, key questions remain over the future of the Czech flag carrier. Can it remain a niche network carrier, or does its future lie as a regional feeder airline?

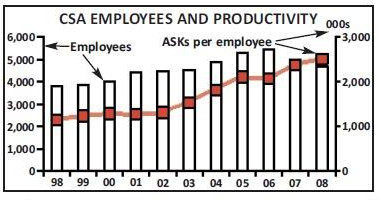

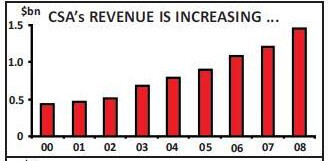

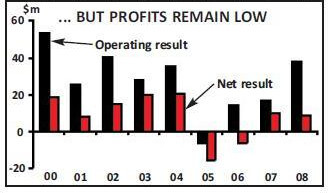

Prague–based CSA operates to more than 60 destinations in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, and has been profitable through the 2000s — albeit at relatively low levels (see charts, below).

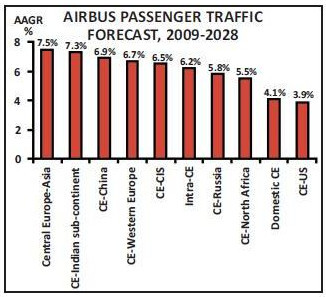

Theoretically CSA is ideally located to take advantage of long–term growth from central and eastern Europe to other markets, and Airbus’s latest market forecast is bullish about growth rates for the central European region (which in its definition includes eastern Europe) over the 2009- 2028 period, as shown opposite.

The Czech state, led by the finance ministry, launched a process to sell its 91.5% stake in CSA in February last year, with a winning bidder scheduled to be chosen by the middle of July. The ministry wanted to raise more than $270m, but from the start imposed a number of conditions on potential buyers, including a requirement that CSA retains its “national airline status” and that it keeps its base at Prague airport for at least five years. To make matters worse, the process itself verged on shambolic — almost inevitably the initial timeline was extended not once but twice (until the end of September), with the ministry’s justification for this being that it would “provide enough time to bidders for valuing the company”.

A hasty shortlist?

In fact four serious bidders came forward over the first few months of 2009, including Air France/KLM, Aeroflot and Odien — a regional private equity fund that owns Cedok, the largest travel agency in the Czech Republic. The fourth expression of interest came from a consortium between Unimex, a Czech financial company (with a 51% interest in the consortium) and Czech charter airline Travel Service (which had a 49% share). Travel Service, of which Icelandair Group owns 30% and Unimex 20%, was the subject of a failed takeover by CSA in 2005, but since then it has expanded into low–cost scheduled services though subsidiary Smart Wings. In April the Czech finance ministry narrowed these potential bidders down to a shortlist of just two – Air France/KLM and Unimex/Travel Service. This was a decision that puzzled some analysts at the time, as with just two entities on the shortlist this didn’t give the ministry much room for manoeuvre if one of the bidders fell away (and indeed that was a mistake that would come back to haunt the process).

Additionally, the decision to exclude Aeroflot from the shortlist also appeared short–sighted, as it is arguable that of all the potential bidders Aeroflot would have been the best strategic fit for CSA, bolstering the Russian airline’s position against Lufthansa in central and eastern Europe and allowing CSA to have a strong partner/owner eastwards.

Aeroflot suspected that the hasty decision to exclude it was at least partly due to a perception among Czech politicians that Aeroflot ownership of CSA would have presented “a security threat for the Czech Republic”. Indeed the finance ministry had said that it needed to check whether "any of the bidders is directly or indirectly owned by state–owned entities of countries whose foreign and internal policies pose security risks for the Czech Republic", although it subsequently never mentioned this as an explicit rationale for omitting Aeroflot from the shortlist.

Aeroflot quickly put out a statement that following “a thorough examination of CSA’s financial and operational situation, Aeroflot detected considerable risks in the bid, which would have entailed serious financial obligations at a time of a global financial crisis”. That’s partly an attempt to save some face for the airline, but may also reflect concern from the National Reserve Corporation, which owns a substantial minority of Aeroflot, that an Aeroflot purchase of CSA would not be sensible given that the Czech carrier would subsequently need substantial investment.

Down to just one...

Nevertheless, there’s no doubt that Aeroflot’s management was disappointed not to get onto the shortlist, and it had started to look for a local Czech partner for its bid, given that as a non–EU airline Aeroflot would have been capped at a 49% shareholding. Question marks over the ministry’s decision to rule out Aeroflot were underlined in August when Air France/KLM withdrew its interest, apparently due to the downturn in the global economy in general but more likely as the result of a reassessment following an in–depth examination of the finances of CSA – even though CSA’s route network was considered to be “highly complementary” to AF/KLM‘s and would have enabled the French/Dutch group to expand significantly in central and eastern Europe.

Rather unhelpfully for the last remaining bidder, AF/KLM said that: “Under such circumstances, Air France/KLM believes CSA might focus on developing and implementing a standalone recovery plan aimed at restoring its profitability.”

That last bidder was Unimex/Travel Service, which — with no rivals in the picture — went on to bid a reported CZK1bn ($58m) for the state’s share. Incidentally the advisor to CSA, Deloitte Advisory, had indicated that CSA’s minority shareholders would be approached so that the purchaser of the state’s 91.5% might be able to win 100% control; the other shareholders are insurance company Ceska Pojistovna (4.3%), the city of Prague (2.9%), the city of Bratislava (1%) and the Slovak Republic National Property Fund (0.2%)

But in late October the ministry rejected this bid due to a number of so–called “unacceptable” conditions requested by Unimex/ Travel Service, including an injection of funds (believed to be many billions of koruna) by the ministry so that there was “no negative equity” when CSA was taken over.

The low price must also have been a consideration for the ministry, although the consortium pointed out that “in the context of billions in annual losses at CSA, billions in loans due in the next 10 years and more than 14 billion koruna in leasing payments, our bid was above standard".

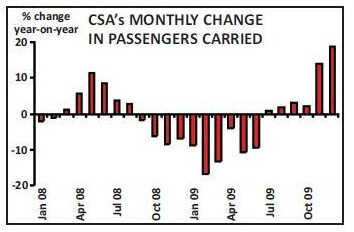

This effectively brought to an end the 2009 privatisation attempt, with the government saying that instead the airline would continue with restructuring. Those efforts have been ongoing for some time — in 2008 pay for all managers was frozen (with board members taking a 15% salary cut) and cost–cutting was intensified after poor financial results for the first–half of 2009. In that period CSA reported a £100m net loss, its worst–ever performance for the first six months of a year. In the half–year revenue fell thanks to a 9.6% drop in passengers carried and — most worryingly of all — CSA said that as a result of “a shift in passengers to lower booking classes … yield dropped significantly”.

Following this set of results and the slump in demand over the first part of 2009 (see chart, below), CSA CEO Radomir Lasak said the airline needed to accelerate cost–cutting and take “drastic” actions, including staff reductions, the cutting of routes and the disposal of aircraft in order to return CSA to profitability in 2010.

The fleet of 50 aircraft (as of last year) is being cut by 10% this year (see table, page 11). Three 737s are to be sold and two A310s will be returned to lessors on expiry of operating leases in spring this year. Over the summer of 2009 CSA decided to remove its two A310s from scheduled service and close the route between Prague and New York (SkyTeam partner Delta maintains a service on the sector). While CSA insisted that it would remain a long–haul airline (with routes continuing to central Asian destinations such as Tashkent), these are flown with narrowbody aircraft and cannot be considered as long–haul by any realistic definition. And though late last year CSA said it was following up a code–share with China Eastern on the Frankfurt–Shanghai route from March this year with talks with the Chinese airline about a Prague–Shanghai route from 2011, this would be operated by China Eastern. There appears to be no realistic prospect of CSA returning to true longhaul routes.

Indeed in August the Czech pilots unions CZALPA wrote a letter to the Czech prime minister criticising the airline’s management and in particular its decision to cancel long–haul routes, which the union believes relegates the airline to being a regional carrier only.

All change at the top

In terms of staff, in August CSA told unions that it wanted to make 860 redundancies at the airline (out of 4,600), to be implemented in all parts of the airline (including 140 pilots, out of the total 560, and 240 cabin crew) between September and March 2010. But that ambition ran into substantial opposition, and so in October the company said it wanted to cut salaries substantially, with the board promising to resign as soon as unions signed new collective agreements with cuts of 30% on pilot salaries, a 15% reduction in other salaries and a freeze on all other employee benefits until at least the end of 2010. This deal was agreed in October (just a week before the finance ministry rejected the last remaining bid for CSA) with chairman Vaclav Novak, CEO Radomir Lasak and six other board members resigning in the same month. Miroslav Zamecnik took over as chairman and Miroslav Dvorak, head of Prague airport, became CSA’s new CEO. However, Dvorak has kept his position at Prague airport, which has inevitably led to charges of a conflict of interest – although as both the airline and airport are owned by the government, CSA denies this accusation. But in November CSA then replaced chairman Miroslav Zamecnik with Michal Mejstrik, and also cut the management board from nine to five members and the supervisory board from 12 to six members.

Although Dvorak says that the airline is not under pressure to sell assets to raise cash and should be able to raise finance through commercial debt, it’s clear that the airline is disposing of as many non–core assets as possible in order to raise cash. After selling its headquarters in Prague to the operator of Prague airport, in December last year CSA agreed to sell its duty–free business (which has 80 employees and earns annual revenue of more than $30m) to a company called Aelia Czech Republic, a joint venture between two companies owned by Lagadere Services, a French retail and distribution group. The sale raised $42m, which will be used for "implementation of further stabilisation measures", according to the airline.

Sixth-freedom strategy

In January CSA also created a subsidiary called CSA Support into which it placed all its handling operations. The unit has more than 800 employees and with profit and loss accountability, this leaves the possibility open in the future of a sell–off by CSA. In terms of its route network, CSA’s new strategy appears to be focused on sixth–freedom routes. After the last bidder was rejected in October, the finance ministry’s future for the airline relied on deeper restructuring, along with a route strategy that is explicitly based not on point–to point routes from Prague (in which there is fierce competition and which has a “self–destructive price war”) but rather on building up sixth–freedom routes in Europe as well as increasing charter operations (with the A310s taken off long–haul being used for charter operations prior to their disposal).

The airline believes the market potential of sixth freedom routes though Prague — connecting its destinations in Europe, the Middle East and central Asia — is three times larger than the point–to–point market out of Prague. That may be an overgenerous assessment of the potential, because transiting through Prague is unlikely to be an optimal solution for many of the city–pairs in CSA’s route network.

Nevertheless this is what CSA intends to do, and in order to build up this revenue late last year CSA introduced a new fare management system called “Origin & Destination”, which can generate fares for almost 4,000 connections in its network through Prague. At the same time, in the winter 2009/10 timetable CSA began to close “financially inefficient” point–to–point routes, including services to Manchester, halted its long–haul flights to New York JFK, and reduced frequencies to destinations such as London, Riga, Hamburg and Ostrava. However, frequencies were raised on some routes to eastern Europe, including Moscow, Tbilisi and Minsk.

Overall, the prospects for CSA’s survival as a standalone network carrier are poor. The finance ministry believes CSA can return to profitability without the need for outside help, but that seems a very optimistic assessment. The sale of non–core assets will reach a limit at some point, and the new strategy of a sixth–freedom network via Prague looks risky. Already the expected date for a return to profitability has been shifted from 2010 to 2011, and with the long–haul routes now gone the danger is that CSA is slowly turning itself into a regional carrier. That may make the carrier much less attractive to a potential buyer if the finance ministry resurrects a sale — which it surely will do at some point.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| A310 | 2 | ||

| A319 | 7 | 9 | |

| A320 | 8 | 4 | |

| A321 | 2 | ||

| 737-400 | 7 | ||

| 737-500 | 10 | ||

| ATR-42 | 8 | ||

| ATR-72 | 4 | ||

| Saab 340B | 1 | 9 | 4 |

| TOTAL | 49 |