Aer Lingus – kissing goodbye to simplicity?

March 2010

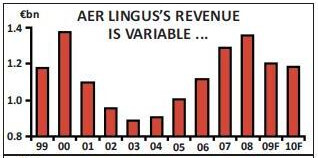

Aer Lingus has arguably been the hardest hit of all the legacy carriers by the rise of the new generation LCC business model – not the least of its problems being Ryanair’s very existence as an Irish airline and its inexorable expansion in its home base. Indeed Aer Lingus is probably unique among the European flag carriers in finding that it no longer has the largest share of traffic in its home market. So what does the future hold for Ireland’s flag carrier?

Under the stewardship of Willie Walsh as CEO the airline went through a strategic restructuring in the early 2000s designed to recover profitability after the 2001 downturn and reorient itself as a new generation low cost carrier – on the rationale that as its main competitor was Ryanair, and as it could not hope to beat its main competitor as a full service legacy carrier, it should try to reinvent itself as benchmarked against the new generation business model.

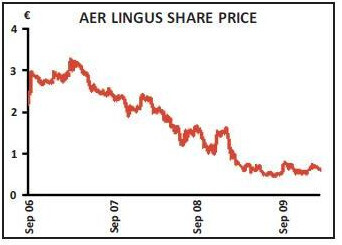

This restructuring at least was able to bring the cost structure a little closer to the “keep it simple” principle of its major competitor and to some extent it has been able to hold its own against Ryanair. And it was at last able to float on the stock exchange in 2006 – even if it was to be lumbered immediately with an audacious and unwanted bid from its cash–rich arch–rival.

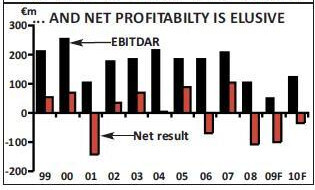

The LCC restructuring under Walsh established Aer Lingus as an unusual hybrid: a legacy carrier with very low operating costs. In the process the company removed some €350m from its cost base (30% of its costs in 2001) and although Walsh was not quite able to achieve his target of a 15% operating margin by the time he left in 2005, he had achieved the remarkable result of reducing unit costs to what would normally be a highly competitive €5.5 cents/ASK (and that with a relatively short stage length) – albeit still 60% higher than those at Ryanair.

Taking the simplicity principle to heart he turned the airline into two: on the one side being a point–to–point low fare short–haul operator by unbundling the product, simplifying procedures, outsourcing non–essentials, adopting a single class short–haul operation, significantly improving employee productivity, distributing via the internet only, implementing a load–factor static/yield active low fare revenue management system and pursuing further reductions in unit costs. On the other side was a point–to–point transatlantic carrier to those few major Irish destinations in the US it could operate to – although still then stymied by the restrictive Irish–US bilateral – but one starting to look at expanding in other directions.

In the process Aer Lingus also withdrew from its previous alliance partnership in one world, although retaining major code–share agreements (e.g. with British Airways on the Irish–UK routes) while seemingly disowning pretentions to act as a traditional network carrier.

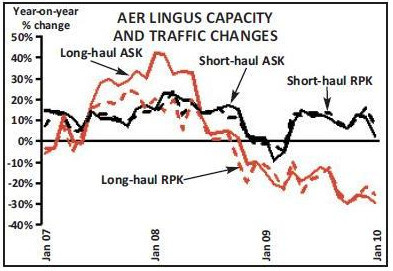

Having seemingly nearly sorted its cost structure the company grew strongly in the upturn in the cycle; between 2005 and 2008 it expanded capacity by an annual average 10%-13% on long–haul and 15% on short–haul — while demand could not keep pace with the increase in capacity and load factors fell by 15 points to a disappointing 71% on long–haul operations (which included some questionable but short–lived services to the Middle East) and by three points to 74% on short–haul.

Of course when the financial crisis and the collapse of Lehman Bros arrived at the back end of 2008 the world changed. Ireland was particularly badly hit. The Irish economy had benefited substantially from its adoption of the Euro in 1999 and the eurozone’s low interest rates, and had overheated in the subsequent eight years. This overheating naturally led to an inverse reaction in the downturn: Irish GDP probably fell by more than 7% in 2009 and is expected to decline by an additional 2.5% in 2010. All airlines have been hit badly – but Aer Lingus more than most. Traffic to/from Eire slumped by 25%, exacerbated by the weak economy and the strength of the Euro against the Dollar and Sterling (the UK being its largest trading partner) and not helped by the introduction of a “tourist tax”.

All change

In the first half of 2009 the company posted a substantial operating loss of €93m (almost twice the operating loss it suffered for the full disastrous year of 2001) on revenues of €555m that were down 12% year–on–year — compared with an operating loss of €23m in the same period of the previous year. It even achieved the ignominy of an EBITDAR loss of €25m. Net cash balances fell to €440m, prompting Ryanair to suggest that the Irish flag carrier would soon run out of cash. A year ago Aer Lingus appointed a new chairman – Colm Barrington (another former sparring partner of O'Leary’s from GPA days) while in October Christophe Müller (formerly of TUI and Sabena) took over as the new CEO. In January the company held an 'investor day' in London to introduce the CEO and explain the company’s new strategy to the investment community. He started off by outlining his first impressions:

- Assets: a strong balance sheet, with €825m in gross cash; a modern streamlined fleet – slightly more than half owned outright; a valuable route network; and strategic slots (particularly at Heathrow).

- Operating business: a very competitive cost base; high quality maintenance; and good asset utilisation.

- Markets: a strong brand in core markets; a high market share on core routes; and underutilised route connectivity.

- People: high calibre staff; excellent customer satisfaction; and positive staff attitudes. However, against this was a business that needed immediate short–term remedial action to halt losses and preserve cash — through capacity reductions, yield improvements and cost reductions. In the longer term he stated that the company needed a clear and coherent direction to drive profitable growth when the world finally returns to some form of normality. This meant reassessing:

- Market positioning,

- Network design,

- Partnerships and alliances,

- Yield management,

- Distribution, and

- An antiquated IT infrastructure.

Short-term actions

As for many airlines, 2009 was a year of mixed fortunes for Aer Lingus. In the first six months the company continued to increase capacity and maintained an over–aggressive expansion of the network – including an attempt to break into easyJet’s increasingly monopolistic position at London Gatwick. Not helped by Ryanair’s aggressive pricing initiatives it found yields under extreme pressure – exacerbated by the focus on maintaining load factors at all costs. Added to which Müller stated that he believed they were in a “vertical section” of the demand curve where price manipulation would not stimulate traffic. At the same time the cost base — not helped by the prior year fuel hedging programme bringing in fuel costs well above market rates — was “too high for market conditions and the scale of the business”. The result was a massive €94m loss – or 17% of revenues. In the second half of 2009 (which includes the all–important main summer season) he stated that the company anticipates a small profit before exceptional items. This has been achieved by a reduction in long–haul capacity, including the cutting of the dubious Middle East routes and others (such as San Francisco), along with frequency reductions across the board. The initial foray into Gatwick had been cut back significantly by reducing the number of aircraft based there from five to three and concentrating on core routes to Dublin, Cork, Knock and Malaga. The result was a near 20% reduction in capacity in the final quarter of the year. Importantly on yield, the company started to refocus its capacity management policy towards the traditional aim of maximising unit revenues per flight (or seat) rather than concentrating on load factor maintenance.

Along with the rest of the world Aer Lingus has rescheduled its future aircraft deliveries. In 2009 it ended with a fleet of 44 aircraft (and outstanding orders for 14), with an average age of six years. There are 36 A320/321s on short–haul operations and eight A330–200/300s on long–haul (and of the total fleet 48% are leased and 52% fully owned). Two additional A320s originally due for delivery in October this year have been deferred by six months. Three further A330s (which could be converted to A350s) have been deferred from 2010/2011 by three years while four A350s scheduled for 2014 have been pushed back a year. This will help capital outlay plans significantly (apparently having been done without any penalty from Airbus), bringing capex down towards €50m by 2012 from the €170m anticipated in 2010 – although from 2015 it appears Aer Lingus will suffer an average annual capital cost on equipment of more than €200m a year.

Medium-term options

At the same time the company has introduced the necessary restructuring/cost saving plan – imaginatively called “Greenfield” and designed to save a further €97m from the cost base as well as realigning the company to prepare for “the next stage of growth”. It is a bit surprising that Willie Walsh had left something to slash further after his time in the driving seat, but apparently there is additional room to cut management overheads, by reducing management levels from six to three. This will result in reducing staffing levels by 500, including a 40% reduction in management positions, reductions in pay and an anticipated cut in total staff costs from €310m to €240m by 2011. Uniquely it appears that the company has managed to get the pilots to agree to a suspension of the seniority list to enable the retirement of the older and more expensive on the roster. The CEO’s presentation highlights his aim of profitable growth once markets recover. Underpinning this strategic thinking is an investment in underlying IT platforms to bring old systems up to date (some of which go back decades). This will possibly allow the company to turn its yield (or capacity) management model towards the network carriers' modern norm of a true O&D system. Inherently this means turning the operating philosophy away from the LCC model back towards the greater complexity of a network carrier. Aer Lingus aims to “seek access to latent demand” through “network enhancement”, partnerships and once again accessing other distribution channels apart from just the internet (and tailored to each originating market).

However, a key problem remains that the demand profile for Aer Lingus (with its base in a small nation on the periphery of Europe) is weak.

Eire is one of the smallest countries in Europe by population – although to its 4.5m inhabitants should probably be added the 1.8m living in the six counties north of the border as part of a natural catchment area. However, it does have a huge diaspora: 10% of the English population (or 6m people) have at least one Irish born grandparent, while 25% (or 15m) claim Irish descent; while in the US it is estimated that more than 40m people are of Irish descent. As a result, although the underlying population of Ireland does not give rise to a strong natural base for point–to–point O&D traffic, there is a substantial potential for VFR and leisure travel, and a huge advantage for air travel is that Ireland is an island. But as the figures in the table (above) show, the country has an unusually low level of business traffic – accounting for only 13% of total visitor arrivals – and a high proportion of leisure and VFR arrivals at 53% and 28% respectively.

It is a truism in the travel business that these latter two categories are the most price and income sensitive and least time–sensitive – although Ryanair’s O'Leary recently quipped that VFR traffic was some of the most lucrative for his airline, especially when the passenger just had to get to a funeral – and the least loyal.

The company further highlighted that as a result of this it has a relatively low proportion of demand for high–frequency time–sensitive services – and with that demand concentrated on a very few routes (principally the UK–Ireland routes, the most important of which is the Dublin–Heathrow route).

Strategically it may well be that the pure LCC model as an experiment for a legacy carrier such as Aer Lingus does not fit well – and Müller was at pains to point out that he believed that it was no longer a sustainable model for anyone; with a lack of any further opportunities for acquiring deeply discounted aircraft in the way that Ryanair and easyJet fuelled their aggressive growth in the 2000s (although have Boeing and Airbus really become rational?).

At the same time it is now impossible for Aer Lingus to revert to the full service legacy model; the low fares created by the Ryanair phenomenon are ingrained in the Irish market place, there is a very low proportion of business travel in its markets, and it is on the periphery of Europe.

The new aim is therefore to re–emphasise a market position as a hybrid midway between the full service flag carriers and the ultra–low cost carriers. As a result the company will effectively attempt to take least onerous of the complexities of the network model and combine it with the unbundling of the product inherent in the LCC model:

- Central airport locations,

- Business and leisure products,

- “Quality” core product with select à la carte paid options,

- Standalone FFP with reciprocity with partners,

- “Medium customer expectations,”

- Distribution through the internet as a priority, but multi–channel depending on market, and

- Specific network connections at selected hubs.

Having turned its back on the seeming impossibility of operating its network as a connecting hub, while at the same time having a very low level of high value point–to–point demand for its long–haul services, Aer Lingus has now announced a code–share agreement with troubled regional carrier Aer Arann. Müller identified that for certain regions in the UK there is reasonable — albeit not substantial — demand for services on the Atlantic that are currently better served through London’s “third” airport at Amsterdam than through either Heathrow or Gatwick.

Partnerships/alliances

In addition, although the company had turned its back on promoting network connectivity through its hub, Aer Lingus still has a natural fit between short–haul arrivals and long–haul departures to allow it to market shortest total trip times — e.g. between Glasgow and Boston in both directions. Although it does not matter for internet bookings necessarily, offering such connections makes it appear higher up the list for total trip times in the GDS engines. An additional marketing advantage not offered by any other hub in Europe is the US immigration and customs pre–clearance available at Shannon and Dublin T2. Admittedly Aer Lingus would only be able to offer connections on New York, Boston, Chicago and Orlando – but it has ambitions to promote additional connections on partners (such as JetBlue through JFK or United at ORD) to onward points in the US. Surprisingly perhaps, it appears that the only long–haul route the company operates that “works” as a point–point service is that to New York; the others would have to generate additional traffic from transfer at either end to survive. Aer Lingus has a long standing close relationship with British Airways (although it withdrew from the one world alliance during its restructuring towards an LCC business model), now principally as a code–share partner for Irish routes to and through London and delivering 150,000 sectors a year. (With the low fares inherent in the Irish market place even BA could not compete on the routes, while Aer Lingus’s 20 slot pairs at London’s constrained airport are probably the most valuable assets not on its balance sheet). It also has a similarly strong code–share partnership with KLM through Amsterdam to the Far East and Africa. Two years ago Aer Lingus set up a code–share partnership with JetBlue through JFK and Boston to some 40 beyond destinations, and following the introduction of the first stage of the EU–US Open Skies agreement set up code–shares on 35 domestic destinations with United. As a result Aer Lingus is effectively gaining network benefits from all three global alliances, and there may appear to be more downside to Aer Lingus from being more closely related to just one of them.

On top of these relationships, and apparently described in Washington as “the most intelligent use of Open Skies”, Aer Lingus and United have set up a unique joint venture on the Atlantic that helps to solve a part of each carrier’s deep–seated problems. Aer Lingus has too many long–haul aircraft and finds it exceedingly difficult for its long haul–routes to make economic sense: UA has a lack of long haul lift (although it has some 777s on option it has none on current order). Under this “extended code share” Aer Lingus will initially introduce a service (to start in March this year) between Washington and Madrid under its own colours as an effective wet–lease, being responsible for the operational aspects while United will be responsible for revenue generation (with the service being offered under both carriers' codes). Both airlines equally share the economic benefits and risks, and depending on the outcome may expand the agreement into a broader joint venture.

Müller may well be right in his conclusions — that Aer Lingus is fundamentally an attractive airline, that the short–term measures taken will stop the cash haemorrhage, and that the Greenfield restructuring will dramatically alter the cost base and provide opportunities for profitable long–term growth once market conditions improve. Certainly it helps to have a cash pile of €825m (93% of which is unrestricted). It definitely helps that on its core London Heathrow routes its other competitor, bmi, is retrenching. And it may well help that Aer Lingus’s aggressive Irish competitor has decided to slow growth and not take any more aircraft. But all this does not solve the fundamental issue of the restriction and embarrassment of having Ryanair sitting vulture–like as a 30% shareholder.

| Visitors by reason for travel | ||||

| Business | 13% | |||

| VFR | 28% | |||

| Leisure | 53% | |||

| Other | 6% | |||

| Total | Vistors by region of travel | 100% | ||

| North America | 7% | |||

| UK-Air | 39% | |||

| UK-Sea | 8% | |||

| Europe | 46% | |||

| Total | 100% | |||

| Source: CSO. | ||||