JetBlue: slower growth and new revenue strategies

March 2008

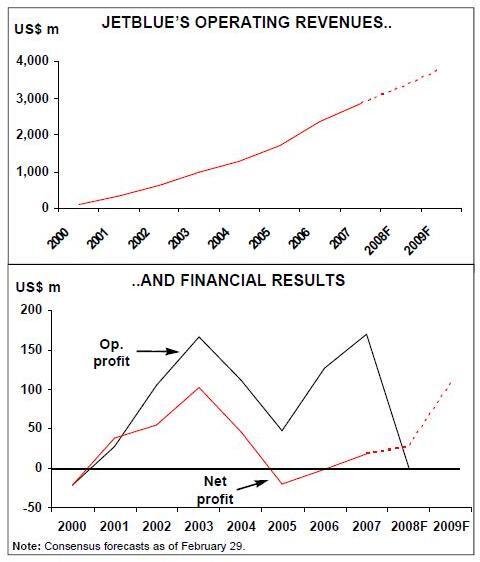

JetBlue Airways, the largest of the new generation US LCCs, is in the middle of a financial turnaround, thanks to two years of restructuring and strategy refinements.

The New York City–based airline has retained its superior product and low cost structure, but in other ways it looks very different: a new leadership team, more sophisticated revenue management, a disciplined growth strategy, new types of markets and a focus on high–yield passengers and international alliances. Will this new type of hybrid LCC/traditional model work for JetBlue? JetBlue, which commenced operations from New York JFK in February 2000, had perfect credentials: ample start–up funds, a strong management team and a promising growth niche. It succeeded in attaining Southwest’s efficiency levels, despite its high–cost Northeast environment, much smaller fleet and a more up–market product.

JetBlue became profitable after only six months of operation and went on to achieve spectacular 17% operating margins in 2002 and 2003.

With its new A320 fleet, state–of–the–art technology and superior in–flight product, JetBlue also set new standards in airline service quality in the US. Like Southwest, it quickly built a "cult following", which has enabled it to attract price premiums and considerable customer loyalty.

JetBlue also grew extremely rapidly, achieving "major carrier" status, with $1bnplus annual revenues, in 2004 — its fifth year of operation, which is by far the fastest–track to a major ever seen in the US. Last year JetBlue had $2.8bn of revenues, making it the eighth largest US passenger carrier.

However, after the spectacular start, JetBlue stumbled financially just as the rest of the US airline industry began to see light at the end of the tunnel. In two years, JetBlue literally went from the industry’s best to worst in terms of financial results. Its operating margin plummeted from 17% in 2003 to 8.8% in 2004 and 2.8% in 2005. 2005 and 2006 saw net losses of $20m and $1m, respectively.

The main reason for the losses, of course, was the hike in fuel prices. Like most US airlines, JetBlue did not have significant fuel hedges in place.

Like other LCCs, JetBlue also found it harder than the legacies to deal with the weak domestic pricing environment. It had no lucrative international operations. Its simple pricing model meant that it had few fare buckets to play with. And its aggressive growth plan required it to focus on filling aircraft rather than pricing for profitability.

JetBlue was the fastest–growing US LCC in the first half of this decade. It continued to grow ASMs by 21–25% annually in 2005 and 2006, despite the financial losses, because there was no demand problem and because it did not want to forego good growth opportunities.

Although JetBlue began to tackle its problems in the spring of 2006 with a "return to profitability" plan, the most visible actions came following an operational meltdown on Valentine’s Day in February 2007 that highlighted serious shortcomings in the airline’s ability to deal with operational issues.

An ice storm in the Northeast grounded 1,000–plus flights, and because JetBlue had a policy of not cancelling flights ahead of bad weather, thousands of people were trapped in aircraft for hours or stranded in terminals for days.

JetBlue did not fly a full schedule for days. There was a massive outcry from air travellers and calls from Congress for legislation to protect passengers' rights.

JetBlue averted the crisis — and fortunately suffered no lasting negative impact on image or customer loyalty — by taking decisive action. The airline made important changes in the way it responds to weather and other operational irregularities, drafted its own "customer bill of rights" and strengthened its operations team.The February 2007 crisis also led to a leadership change three months later.

JetBlue’s board ousted CEO David Neeleman and named President Dave Barger to succeed him. Neeleman had been criticised for spending too much time apologising rather than fixing problems; however, the changeover was seen more as a natural progression in the leadership structure as JetBlue matures. It was hoped that Barger’s appointment would bring more stability internally and help facilitate more orderly growth. Neeleman remains JetBlue’s chairman, and holds about 4% of the carrier’s stock.

Since introducing the financial recovery plan in April 2006, JetBlue has tackled many of the issues with great success. Most significantly, it has drastically slowed growth through fleet reductions. Second, JetBlue has improved revenue generation (in a very difficult domestic pricing environment) through a multitude of initiatives and strategy changes, and it continues to enjoy robust RASM trends in 2008.

Third, JetBlue has enhanced profitability through network changes. Among other things, there has been major Caribbean expansion and a shift to higher–yield short and medium haul markets utilising the E190 — strategies that have helped reduce over–dependence on the transcontinental market.

Fourth, like many other US LCCs, JetBlue is moving decisively to develop ancillary revenues. It is now going all out to market its subsidiary LiveTV, which should be a good revenue generator in the short term and a spin–off candidate in the longer term.

As a result, JetBlue returned to profitability in 2007, posting operating, pretax and net earnings of $169m, $41m and $18m, respectively (6%, 1.4% and 0.6% of revenues).

This was a real achievement in light of the fuel price hike, the February ice storm (which meant a $40m revenue hit) and last summer’s terrible flight delays in the New York area.

JetBlue has basically returned to industry "mainstream" financial performance. Its 6% operating margin was slightly higher than the legacies' typical 5–5.5% margins, the same as AirTran’s 6%, but well below the 12.2% and 8.7 margins achieved by Allegiant and Southwest in 2007.

More disciplined growth

Slower growth has been the key factor behind JetBlue’s financial recovery. The airline reduced its ASM growth from an annual average of 25% in 2003–2006 to 12% last year. For a while it looked like around 10% would become the norm, but growing economic uncertainty prompted JetBlue to twice scale back its growth plans in January. The current plan calls for 5–8% ASM growth in 2008, but further revisions are possible if the economic picture worsens.

The ASM growth reduction has been achieved through a combination of older aircraft sales, lease terminations and order deferrals with Airbus and Embraer. In 2006 JetBlue sold five A320s in the used aircraft market. In 2007 it sold another three A320s,returned one leased A320, deferred four A320 deliveries from 2009 to 2012 and deferred 16 E190 deliveries from 2007–2012 to 2013 and beyond. In January JetBlue disclosed that it had deferred the delivery of 16 A320s from 2010–2011 to 2012–2013. It also currently has commitments to sell six A320s in 2008 and is open to selling more, if necessary.

The airline also intends to manage capacity through aircraft gauge reductions (substituting E190s for the A320s) and by reducing utilisation in off–peak periods.

JetBlue is lucky to have one of the highest aircraft utilisation rates in the industry — still averaging 12.8 hours daily on the A320s — which gives it flexibility in the current fuel environment.

The A320 and E190 options help JetBlue maintain flexibility to accelerate fleet growth and respond to market opportunities. For example, in December the airline exercised three E190 options for 2009 delivery. JetBlue is scheduled to take delivery of 12 A320s and six E190s this year. Assuming six A320s are sold, the year–end 2008 fleet would be 110 A320s and 36 E190s.

Including the effects of the January Airbus order amendments, at the end of 2007 JetBlue had 70 A320s and 74 E190s on firm order for delivery through 2015, plus 32 A320 options and 91 E190 options for 2009- 2015 delivery. The firm order deliveries amount to 18–25 annually in the next six years.

Improved revenue generation

The April 2006 recovery plan instigated fundamental changes to JetBlue’s revenue strategy. In David Neeleman’s words at that time, fuel simply changed the way the airline looked at the world. The premise of the previous model, which worked well when crude oil was at $20–30 a barrel, was to keep costs and prices low and make substantial profits on volume and growth. Now the time had come to sacrifice some load factor to the yield.

The aim was to get the system average fare of $105 up by "a few more dollars" to cover the increase in fuel prices. JetBlue did not want to change its low fare structure; rather, it wanted to improve the fare mix.

This meant a move towards conventional yield management and more complexity in the pricing model — strategies that European LCCs like Ryanair have used successfully since their inception. JetBlue upgraded its yield management systems and revamped its revenue management team. The spring and summer of 2006 saw a multitude of revenue initiatives, including selective capacity cuts, scheduling adjustments, adjustments to fare buckets, elimination of some of the cheapest fares and new corporate booking tools.

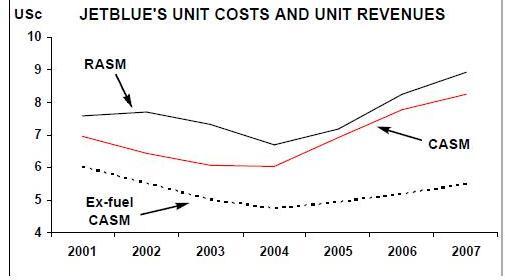

Add to that the slower growth rate, fewer new city additions (which has meant that a large number of markets are maturing) and the increased use of E190s in higher–yield short and medium haul markets (the type was introduced in November 2005), and the results have been quite stunning. Between 2005 and 2007, JetBlue’s average fare rose by $13 or 12%, while the yield surged by 28% and RASM by 24%.

The revenue momentum remains strong going forward also because of competitors' capacity cuts in JetBlue markets, new product offerings targeting the higher–yield segment and a new focus on developing ancillary revenues.

Many of JetBlue’s latest revenue moves are aimed at capturing more business traffic. Last year JetBlue listed its fares in all four major GDSs, which resulted in higher average fares, offsetting the increased distribution costs. In January the airline launched refundable fares — a fare class with a $50–100 premium for passengers needing extra flexibility.

In the second quarter JetBlue will unveil a new "front cabin" product, aimed at monetising the increased pitch on its A320s especially against competitors such as Virgin America. About a year ago, JetBlue removed a row of seats from its A320s, reducing the seating from 156 to 150, which enabled it to operate the aircraft with two (rather than three) flight attendants. The reconfiguration also meant that seats in the first 11 rows (44% of total seats) have an industry–leading 36–inch pitch, while the remaining seats have at least 34–inch pitch. JetBlue planned to reserve some of the front seats for last–minute or first–class type customers and said that it would later roll out "exciting programmes" to boost revenues.

The product to be unveiled in the coming months is the result of those efforts. It will not involve removing more seats from the A320s.

JetBlue’s management has indicated that developing ancillary revenues will be a major focus in 2008. Last year the airline increased its change fees, began collecting a $10 fee for reservations over the phone and launched a "cashless cabin", which will provide a platform for further developing sales on board aircraft. The result was an encouraging 50% increase in "other" revenues in 2007. Like Southwest, JetBlue needs to invest in some technological enhancements to be able to fully meet its ancillary revenue goal.

Selling LiveTV products to other airlines is a highly promising "other" revenue source. A wholly owned subsidiary that JetBlue acquired in 2002, LiveTV had $40m revenues in 2007. At year–end contracts were in place with seven airlines, involving 372 aircraft.

Until recently, JetBlue was careful not to give direct competitors access to the product; however, Continental, JetBlue’s primary competitor in New York, is now the latest LiveTV customer, having signed a long–term contract for its 737s and 757–300s. This represents an interesting shift of strategy on JetBlue’s part. CEO Dave Barger explained recently that JetBlue believed that domestic passengers in the US would soon expect some form of in–flight entertainment and connectivity on flights, so having a LiveTVtype product would be necessary just to keep up with competition. Since the product no longer offers a distinct competitive advantage, JetBlue has decided to begin aggressively pursuing sales opportunities with any airlines.

Unique business model

In the past couple of years, it has often been suggested that JetBlue is moving towards a conventional business model, "toward something decidedly traditional", as one analyst put it. Multiple fleet types, modest growth, GDS participation, international partners, emphasis on high–yield passengers and refundable tickets all point in that direction.

However, JetBlue has always been upscale and it remains one of the lowest cost US carriers and committed to low fares, so nothing has fundamentally changed. JetBlue’s key value proposition and marketing message, as stated in its 2007 annual report, is the same it has always been: "Low fares and quality air travel need not be mutually exclusive". And as CEO Dave Barger put it recently, "our ability to deliver exceptional service at a low cost differentiates us from the rest of the industry".

Back in October, Barger stressed that JetBlue remained a "discretionary airline, a leisure airline by and large" but that there were opportunities to "mine the corporate customer" and that JetBlue needed to go after those opportunities.

JetBlue is merely doing what it needs to do to remain viable in the current fuel environment.

Southwest is moving in the same direction, one difference being that it needs to move cautiously because of its egalitarian image. AirTran, in turn, has had a business class product for about a decade. That said, JetBlue does seem to have a brisker attitude to doing business than the other LCCs — its CEO has used the term "can do" airline. It is less averse to doing unusual deals, such as accepting an investment from Lufthansa.

JetBlue has not departed from its Southwest–style growth strategy of focusing on markets that have high average fares and then stimulating demand with low fares.

Most significantly, JetBlue has retained its low cost structure, despite the increasing mix of the shorter–haul E190s in the fleet and rising A320 maintenance costs, in addition to the fuel price pressures. Asset and labour productivity are high and the latter continues to improve. The management believes that the cost initiatives launched in 2006 have "helped institutionalise JetBlue’s low–cost culture". That said, AirTran has about 10% lower CASM on a stage length and density adjusted basis.

Route network strategy

JetBlue is primarily a point–to–point carrier, earning 90% of its revenues from such operations in 2007. Most of the flights are to or from New York JFK or the other focus cities of Boston, Fort Lauderdale, Long Beach and Washington DC. The carrier serves about 53 cities in 21 states, Puerto Rico, Mexico and the Caribbean.

International services accounted for 4% of total revenues last year.

Route expansion in the past couple of years has had three main themes. First, there has been significant Caribbean expansion. Second, there has been a modest shift away from transcontinental to short and medium haul routes, associated with the introduction and growth of the E190 fleet (though just last month JetBlue announced significant new transcon and West Coast expansion). Third, JetBlue is increasingly overflying JFK due to congestion issues; for example, operating upstate NY to Florida point–to–point services with the E190s.

However, JetBlue is also determined to maintain its leading position in New York. In addition to growing JFK outside the daily peak periods, it has added service from LaGuardia and Newark, as well as the two satellite airports of Stewart Field and Westchester County. About 66% of its daily flights have one of those airports as either origin or destination.

As a result of the new strategies, in the past two years East–West services' share of JetBlue’s total capacity has fallen from 55.1% to 47.4%, while Caribbean’s share has increased from 6.4% to 10.6%. Northeast–Florida has declined slightly from 33.5% to 31.8%.

Reflecting its more disciplined approach to route profitability, JetBlue is, first of all, adding fewer new cities. After launching 16 new destinations in 2006, last year saw just five and 2008 will also see only five. The focus will be on connecting the dots and boosting frequencies. Second, as a result of a network profitability review, JetBlue recently exited two cities (Nashville and Columbus) and discontinued Fort Lauderdale–Oakland service.

The Caribbean expansion has been from JFK, Boston, Fort Lauderdale and Orlando and has taken JetBlue to places such as Cancun in Mexico, Bermuda, San Juan, Santo Domingo and Aruba. JetBlue calls the Caribbean "a natural out of New York". The markets are strong, have year–round demand, have matured quickly, generally require minimal up–front capital and, in spite of limited daily frequencies, are relatively low–cost.

Encouraged by the Caribbean experience, JetBlue has applied to serve Bogota (Colombia) from both Fort Lauderdale and Orlando (pending approval). It would be the first US LCC in that competitive market.

JetBlue is not planning major expansion into South America but believes that there are opportunities for an LCC to serve the region from the Northeast or Florida. Both the A320 and the E190 are over–water- equipped, long range aircraft.

JetBlue believes that the E190, with its near–2,000–mile range, is "perfectly situated as a pathfinder in many of those markets, say Florida–Caribbean". The airline is also considering utilising the E190 in off–peak periods in the Caribbean.

Not everyone is convinced that the E190 will be a good choice for the Caribbean.Raymond James analyst Jim Parker observed in a recent research note that "it remains to be seen if this higher unit cost aircraft is appropriate for leisure destinations that are typically characterised by lower fares".

But the 150–seat A320 and the 100–seat E190, because they offer sufficiently different sizes, seem to be a nice combination for JetBlue’s diverse East Coast operations. The E190 JFK overfly Northeast- Florida services have apparently performed very well and continue to be expanded. The E190 is ideal for developing thinner markets and maintaining frequencies in seasonal trough periods in markets.

The E190’s technical dispatch reliability is now close to the A320’s and average daily utilisation has improved to 10.6 hours. After hitherto utilising it only in the East, JetBlue will be introducing the E190 on the West Coast in May. Despite the current fuel price environment, the management believes that the economics and operating flexibility of the E190 give JetBlue a significant competitive advantage.

Last month JetBlue announced a major expansion of transcontinental flying and significant new service on the West Coast from May. The airline will start serving Los Angeles from JFK and Boston to complement its existing transcon operations to Long Beach, Burbank, Ontario and San Diego in Southern California. It will also introduce a first–ever Washington/Dulles- Burbank nonstop service and extensive West Coast operations from Los Angeles and other Southern California airports to cities such as Austin, San Jose, San Diego, Las Vegas and Seattle. The E190 will debut in Long Beach, though most of the intra- West Coast services will utilise A320s.

This move seems to be a response to Virgin America, which began operations out of San Francisco in August, and is aimed at maintaining JetBlue’s position as the leading LCC in the transcontinental market (where it offers more nonstop flights than any other LCC). JetBlue will then face VA head–on in the JFK–Los Angeles market (along with American, Delta and others). It will also compete directly with Alaska and Southwest in some of the intra–West markets.

JetBlue is more exposed to VA than any other US airline. JPMorgan analyst Jamie Baker calculated last summer that in the Northeast–Northern California market alone, $220m or 9.5% of JetBlue’s total passenger revenue was at risk.

While JetBlue is concerned about the additional competition, it has been dealing with fierce competition in its markets since its inception. Also, JetBlue truly believes that it is well positioned to compete against VA because of its extremely strong position in New York, the multiple airports it serves in Southern California and the Bay Area, its high frequencies and its very competitive product (including its 34–36 inch seat pitch throughout the aircraft, plus the soon–to–be unveiled new front cabin product).

JetBlue is the largest domestic airline at JFK, accounting for about half of the domestic passengers there. Maintaining such a dominant position at JFK is obviously highly desirable, and to that end JetBlue is being helped by two developments. First, JetBlue emerged as one of the winners under the new government–imposed rules to limit flights at peak times at JFK that go into effect this month. The outcome preserves JetBlue’s dominant position, will reduce congestion–related costs, will improve the passenger experience and will limit new competition in the future (improving RASM, etc).

Second, JetBlue will be moving to a new home at JFK, Terminal 5, later this year. The airline expects the state–of–the–art facility to significantly enhance its service and help differentiate it from competitors, as well as facilitate continued growth of operations at JFK.

International alliances

JetBlue has been talking for years about pursuing international alliances, which would help leverage its presence at JFK. About a year ago it finally had a tentative deal with Aer Lingus, but that was only finalised last month. The deal will go intoeffect on April 3. It is essentially an internet booking partnership, apparently the first of its kind between low–fare carriers. Customers will be able to make a single low–fare reservation between Ireland and 40–plus US points via JFK through a booking process available live on Aer Lingus' web site.

Passengers will be able to drop their bags at transfer desks at JFK but will have to change terminals.

JetBlue’s CEO Dave Barger reportedly said that the airline chose Aer Lingus from "dozens" of potential partners because of its low–fare philosophy and because it was the only European discount carrier currently offering scheduled flights to the US.

JetBlue still seems interested in forging partnerships with a large number of foreign carriers, but it appears that, like Southwest, it has more work to do to develop the technology to handle multiple international partnerships and possible code–shares.

In the meantime, JetBlue is in discussions with Lufthansa about a commercial agreement, following the completion, in January, of Lufthansa’s $300m investment in JetBlue, which gave it a 19% ownership stake and a board seat. JetBlue made it clear initially that it saw it simply as a financial transaction, designed to strengthen its liquidity position and give it more financial flexibility in light of economic uncertainty and a possible convertible put option in July. However, in recent statements and conference calls JetBlue executives have mustered more enthusiasm about future cooperation with Lufthansa. In the first place, the two are exploring potential supply- chain opportunities which could yield significant cost savings for JetBlue.

Of course, Lufthansa is believed to be mainly interested in longer–term strategic benefits, such as the sharing of slots and gates at JFK and getting US feed to its transatlantic flights.

Outlook

JetBlue is enjoying a turnaround, driven by a strong revenue momentum. The management is predicting an operating margin of 6–8% in 2008, which assumes extremely healthy 9–11% PRASM growth. According to analysts, the margin forecast implies EPS of 20 cents a share, which would be double the 10 cents JetBlue earned last year.

Wall Street has not accepted that forecast, because of economic and fuel price uncertainty, high execution risk and because JetBlue’s management does not have a good forecasting track record. The current consensus estimate is a profit of 12 cents a share, though the individual estimates range from a loss of 23 cents to a profit of 30 cents. The consensus forecast for 2009 is 48 cents per share. The stock is mainly rated "hold", though some analysts recommend "buy" based on the post–2008 growth and earnings potential.

On the positive side, JetBlue is following sound strategies, its low cost structure remains intact, its culture, image and brand are strong and its financial position is solid enough to withstand a recession.

While JetBlue is highly leveraged, it has modest near–term debt maturities, an excellent cash position of over $1bn, readily monetisable A320s and deep–pocketed investors.