Has Alitalia picked the right saviour?

March 2008

The prolonged and inept attempt to sell the Italian state’s remaining 49.9% stake in Alitalia finally appears to be reaching a conclusion, with preferred bidder Air France/KLM set to complete the deal imminently.

But although most analysts believe the Franco–Dutch group is the best acquirer of an airline that is losing at least €1m a day, has the ailing Italian flag carrier really picked the best white knight?

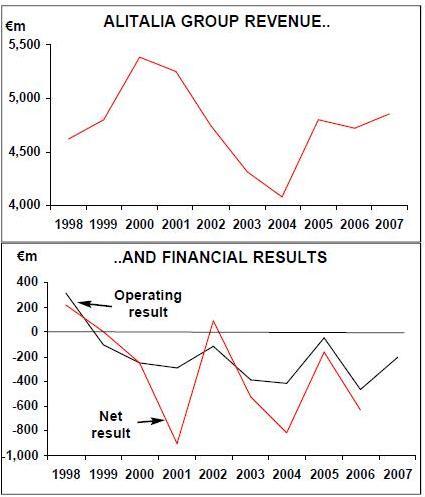

The need for Alitalia to be rescued is obvious. Today the airline employs 11,000 and its fleet of 148 aircraft carried 24.6m passengers in 2007, but despite this scale and the prestige of being a flag carrier, the airline has racked up more than €3bn of net losses since 2000 and last made an operating profit back in 1998 (see charts, page 12).

In 2007 Alitalia reported a 2.8% rise in revenue to €4.9bn, with the operating loss falling from €466m in 2006 to €203m in 2007. While no net figure is available until May (Alitalia had a net loss of €626m in 2006), at the pre–tax level the airline reported a €364m net loss in 2007, compared with a €605m pre–tax net loss in 2006. But this reduction in losses was due largely to the falling away of almost €200m of write–downs of aircraft values included in the 2006 results. Ominously, Alitalia says its 2007 net figure will include the result of another revaluation of its fleet, and the direction of any adjustment will only be downwards.

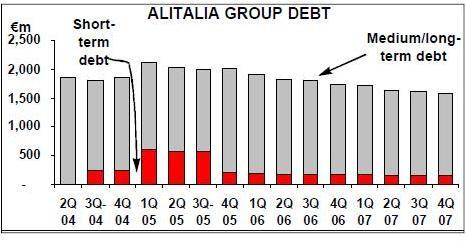

As at the end of 2007, Alitalia has short–term debt of €147m and long–term debt of €1,419m (see chart, right), and after cash and short–term financial credits of €367m are taken away, this leaves the group with net debt of €1.2bn. Alitalia is believed to have enough financial resources to keep going only until the summer of 2008, and certainly does not have enough cash to repay €320m of debt due in 2008 and 2009.

Alitalia’s yield fell 3.4% in 2007, thanks largely to LCC competition, and the airline now warns that its 2008 financial results will be worse than it previously forecast, which will mean even deeper cuts into its cost base.

The airline’s management blames the usual problems of competition, labour unrest and high fuel costs for recent losses, but the underlying reason for Alitalia’s abysmal performance over the years has been a combination of poor management and weak leadership by the Italian government.

Incredibly, Alitalia has had nine CEOs in 10 years and there have been at least five major restructuring attempts at Alitalia since 2003, each one associated with a different set of top management. None have succeeded, and in the meantime debts have mounted and the airline is losing at least €1m a day.

A new beginning?

While its predecessors dithered, the centre- left government of Romano Prodi (elected in May 2006) quickly decided to offload the government’s remaining 49.9% stake in the flag carrier. Yet the first Prodi attempt to sell the stake — by July 2007 — was a disaster and the government had no choice but to begin the process all over again. Maurizio Prato, previously head of Fintecna — the state holding company — was appointed president of Alitalia in August, and was given a range of executive powers.

He described Alitalia’s condition as "comatose", and added that he had "been surprised by the general refusal to accept the reality of how critical the situation is".

At the end of August a new plan was unveiled for Alitalia. The so–called "plan for survival/transition" covers the 2008–2010 period (and is being implemented from March 2008) in an attempt to achieve an operating profit in 2010. At its core is a shrinking of operations, with reductions in routes and an unspecified number of job cuts, with the airline admitting openly that it cannot continue to rack up the losses it is currently incurring.

In essence the plan admits that the airline is weak strategically thanks to the poor geographical position of Italy, where it has little catchment area other than Italy itself (and even here these catchment areas are widely dispersed), and being sub–optimally placed for all the major international aviation sectors. The plan says it would be almost impossible to close the competitive gap with its major rivals based on the realities of Alitalia today, and if it did try to continue to compete in all current routes and markets in an attempt to remain an independent hub airline, "the only result of this attempt would be to confirm Alitalia’s current role as a marginal and 'regional' airline."

Therefore Alitalia believes it has no choice but to scale down its operations, closing both short- and long–haul routes where there is no chance of making a profit in the short–term. This means building up the Rome hub as the prime hub for Alitalia at the expense of Milan Malpensa, which is being downgraded into a point–to–point airport servicing routes not already covered by Milan Linate, and being used much more for Alitalia’s LCC Volareweb and charter carrier Air Europe. According to Alitalia, "the company is no longer able to operate efficiently out of two hubs", but providing Rome Fiumicino can cut its charges to Alitalia and improve its infrastructure, Alitalia would increase routes out of the Rome hub.

The survival plan also envisages a significant capital increase over that period by whoever takes over the government’s stake, since by 2010 the cash position would otherwise not be "adequate". When the 2007 results were announced, the airline said it would probably need at least €750m of fresh capital in 2008 in order to maintain sufficient liquidity, and the situation will get worse if there are any further delays in implementation of the planned restructuring of Alitalia.

How many redundancies this survival plan will lead to was unknown at the time it was unveiled, but not surprisingly the plan attracted plenty of criticism within Italy, from all political spectrums and from Alitalia’s unions. And it’s this plan that has — controversially — effectively framed the government’s second attempt to sell off its 49.9% stake, which Prato promised would be completed by the end of 2007 given the extreme urgency of Alitalia’s financial position. With the government sticking to its message that it will not put any more funds into the airline, the explicit approval of the survival plan by the government signalled that it now accepted a scaling down of Alitalia was inevitable, and that whoever buys Alitalia would be given a free hand to do whatever they needed to. But with the government "presenting" such a plan as coming from Alitalia’s management, those who currently oppose the Air France/KLM bid complain bitterly (and with some justification) that the government has effectively pushed a contraction of Alitalia as being the only possible agenda for a successful bidder.

The new attempt…

For the latest attempt to sell the government stake, the six short–listed candidates named by Alitalia in November 2007 were: Aeroflot, Lufthansa, TPG, Air France/KLM, AP Holdings/Air One and a consortium led by Antonio Baldassarre, an Italian lawyer.

However, the process continued to be shambolic, with the deadline for the latest round of bids somehow slipping from November to December. And by the revised deadline — December 7th — only three potential acquirers remained. TPG withdrew in October when it could not put together an appropriate consortium with enough Italian partners, while Aeroflot withdrew in November, saying that acquiring Alitalia would be unprofitable. Lufthansa — which was widely expected to enter the formal bidding process — at the last minute didn’t make a bid, stating that "the risks outweighed the positives" and that any investment in its SkyTeam partner would affect Lufthansa investment rating negatively.

The list of potential acquirers was down to three: Air France/KLM, AP Holdings/Air One and the Baldassarre consortium (headed by Antonio Baldassarre, who was previously chairman of RAI, the state television station), the latter of which had little chance of success, given its lack of aviation experience.

The original plan was to narrow the field of three down to one for exclusive negotiations by mid–December but — unsurprisingly — after yet another delay, on December 28th Alitalia’s board of directors unanimously choose Air France/KLM as their preferred bidder, citing its "highly credible" business plan — a plan remarkably similar to the survival plan unveiled by Alitalia back in August.

Unconfirmed Italian reports suggested Prato threatened to resign if Air France/KLM was not chosen as the preferred bidder (which perhaps explains the unanimous nature of the decision by the Alitalia board), and the decision was fully backed by the Prodi government. While Prodi had previously said that best bidder should win Alitalia regardless of its "nationality", the finance minister declared the AP Holdings/Air One bid was "excessively optimistic"; while other government sources hinted that an Air One deal may have led to antitrust problems.

An eight–week exclusive negotiation period between the two airlines formally began on January 11th, (expiring on March 11th) at the end of which the government hopes agreement on the details of the deal will have been reached, with Air France/KLM then taking up its option to submit a binding offer to buy the 49.9% stake, subject to approval by the government.

The Air France/KLM bid

Air France/KLM’s shares rose sharply after its bid was confirmed, a reflection of the airline’s close links with Alitalia and the general opinion of investors that a merger of the two SkyTeam partners makes sense.

Essentially, the Franco–Dutch group — which already owns 2% in Alitalia, acquired back in 2003 — offers Alitalia scale, deep pockets and the experience of integrating KLM, and the deal delivers significant political capital and kudos to the Italian government throughout the EU.

Air France/KLM promises a large expansion of routes out of Rome Fiumicino, making it the third hub for the group and providing a southern European base alongside Paris CDG and Schiphol. Alitalia would provide Air France/KLM feed out of the Italian domestic market, as well as on routes to southern and central Europe, and down to north Africa. While there would continue to be some medium–and long–haul services out of Milan, Malpensa would no longer be a major hub airport, and Air France/KLMsays it would support Alitalia’s plan to expand Volareweb flights out of Milan.

With Alitalia saying that 92% of passengers originating from northern Italy do not use Malpensa as their departure airport for longhaul flights, Air France/KLM says that "if the Malpensa hub is not significantly downsized, we don’t see a reason for a deal".

Jean–Cyril Spinetta, CEO of Air France/KLM, says that "a big majority" of Alitalia’s losses arise from the Malpensa operation, with the other major source of losses being long–haul routes. Under Air France/KLM’s plans, Italian passengers to North America could travel via Amsterdam and Paris, allowing Alitalia’s long–haul operation to refocus on eastward routes to the Middle East and Asia.

With reductions at Malpensa and on long–haul, Air France/KLM plans 1,700 job cuts at Alitalia, equivalent to 15% of the 11,000 workforce — although the government is making it clear that it will finance unemployment benefits for those made redundant.

As for the fleet, Alitalia’s 148 aircraft (see table, right) currently have an average age of more than 12 years, thanks to 75 ageing MD80s. Air France/KLM envisages refurbishment of Alitalia’s MD80s and 767s in the short–term, with their replacement in the long–term. Regional subsidiary Alitalia Express, launched in 1997, operates a fleet of 30 aircraft, but Alitalia is believed to be considering its sale.

Air France/KLM proposes to invest a total of €6.5bn in Alitalia over the long–term, most of which will go on fleet renewal and the introduction of lie–flat seats onto longhaul aircraft in order to improve attractiveness to business passengers. Of this total, Air France/KLM aims to invest €750m in an initial injection of capital, and after a "recovery phase", it will then invest in the major expenditure need for MD80 and 767 replacement.

Given this massive outlay, questions have to be asked as to the strategic advantage to Air France/KLM of acquiring Alitalia, because even given Air France’s experience of integrating KLM and the attraction of securing business passenger feed to/from the Italian market, the process of discarding the unprofitable baggage around this feed at Alitalia is likely to be painful.

Spinetta insists that the potential for Alitalia is very strong, with "huge business and tourist traffic flows". Air France/KLM previously stated it would only make a bid for Alitalia if it was certain it would hit a net 8.5% return on its investment by the 2009/10 financial year, so presumably it is confident its plans for Alitalia will achieve this aim, with the Italian flag carrier achieving break–even in 2010 and posting a net profit in 2011.

Air France says that unlike KLM, Alitalia will not be integrated into the Air France group, but rather operate as a separate entity. Spinetta insists that "it has never been our intention to make Alitalia a regional airline, but to strengthen its role as the Italian national flag–carrier and to win back its natural market share".

Clearly Air France/KLM is the preferred option for Alitalia’s management, with Prato saying in December that Air France/KLM’s plans were based on Alitalia’s own restructuring plans (whereas there was little "detail" to Air One’s plans for Alitalia at that date). The only outstanding question on the deal is just how it will be structured financially.

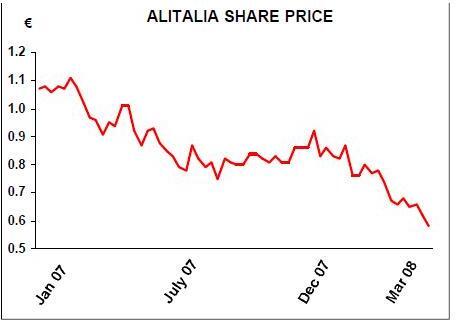

Prior to the exclusive negotiations, Air France/KLM indicated an offer of €0.35 per share, a €750m recapitalisation and the purchase of €1.2bn worth of convertible bonds (which mature in 2010) at nominal value.But although Alitalia’s shares have plunged over the last year (see chart, page 15), they are still substantially above €0.35 per share, so it’s no surprise that the government wants Air France/KLM to increase its bid. In February Air France/KLM said it would invest €3bn in Alitalia over the next five or six years (and €6.5bn in the long–term), and that it wanted to acquire 100% of the airline and then de–list it, subject to agreement by the Italian government to make a full bid.

Given this level of investment and Alitalia’s current financial position, a substantial increase in Air France/KLM’s bid is unlikely. A way out of this problem may be a share swap, which is being considered by both the government and Air France/KLM.

Unconfirmed reports say that the government’s stake in Alitalia could be exchanged for a 3% stake in the enlarged Air France/KLM/Alitalia, and this could even rise to 5% if Alitalia bought back the government’s 51% stake in Servizi, the former Alitalia engineering and ground services division that is now owned 51% by state holding company Fintecna.

Servizi employs 8,500 and Alitalia’s management is urging the Franco–Dutch group to reintegrate the ground services business, but whether Air France/KLM would really want to be burdened with a 100% stake in the service unit (which some analysts believe is substantially overmanned) remains to be seen.

AP Holdings

The bid from Italian LCC Air One for Alitalia is being carried out through AP Holdings, its parent company, which is in a consortium that also includes four banks — Italian–based retail bank Intesa Sanpaolo, as well as Nomura, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

Carlo Toto, chairman and founder of Rome–based Air One, says that its bid for Alitalia would "preserve its national identity", although it is rumoured that an Air One–controlled Alitalia might draw close to Lufthansa in the future (speculation that in January prompted Lufthansa to deny it would be joining the Air One bid for Alitalia).

Air One’s ambitious five–year plan for Alitalia targets a break–even in 2009 and a profit in 2010, with the consortium investing up to €4bn in the airline, largely for mediumhaul fleet renewal that would be at the heart of an expansion of business routes out of Rome–Fiumicino. But in contrast with Air France, Air One says that Milan Malpensa would remain a hub airport under its plans, which envisage an eventual Alitalia fleet of 215–222 aircraft.

While there would be 40 long–haul aircraft, Alitalia’s long–haul slots might be sold off unless they complemented or enhanced Air One’s existing plans to launch long–haul routes in 2008. Up to 20 long–haul aircraft will be leased by Air One over the next four or five years, with approximately four new aircraft a year entering its fleet.

Key to Air One’s initial plans for the flag carrier would be renewal of Alitalia’s regional and medium–haul A320 and A330 fleet, with up to 130 new aircraft coming in at a cost of €3bn. In particular, Air One is looking to shore up Alitalia’s domestic market share, which has fallen to 40% (compared with the 25% of Air One), and there would be rationalisation with Air One’s existing domestic network. Air One has 90 A320s on order, and with the planned new aircraft for Alitalia, an Air One/Alitalia group would have large amounts of new aircraft coming on stream over the next few years.

Air One indicated that Alitalia’s international services would be run primarily on point–to–point routes between Italian and European destinations, while business routes will be concentrated on Milan Malpensa and leisure routes at Rome Fiumicino — although the number of routes will be roughly equal out of each of these airports. By integrating the networks of Alitalia and Air One, AP Holdings says it will take 16% out of Alitalia’s cost base. Its forecasts see revenue reaching €6.2bn by 2012 (with passengers carried of 34.4m), with an EBIT in that year of €375m.

But AP Holdings is offering just €0.01 for each Alitalia share, well below the current share price and the Air France/KLM offer, although this is a more sensible price than the Air France/KLM bid as it allows AP to maximise investment on the airline going forward.

Still in the game

Although Alitalia’s choice of Air France/KLM was a huge blow to the AP Holdings consortium, Carlo Toto is still confident that his bid is not yet dead as he believes it is in the best long–term interests of the airline and the country, and there are reports of at least five new private investors joining the bid since the start of 2008.

Indeed while senior Alitalia management and most of the Prodi government prefers the Air France/KLM bid, and while Air One’s bid to buy its much bigger rival appears to be very ambitious, AP Holdings does have some key allies on its side: the unions (although some of them are now starting to come round to supporting Air France/KLM, after the latter’s lobbying offensive), most of the Alitalia workforce and some powerful political forces, such as the Lombardy regional government. This support is based on Air One’s plans to maintain the size of the Milan Malpensa operation, even though Air One says that it would still need to cut a substantial amount of positions at Alitalia (though less than Air France/KLM).

Air One has long been interested in expanding its presence in Milan’s airports and has been a fierce critic of Alitalia’s takeover of the collapsed Italian Volare group in July 2006. Although the Italian regulator ruled that Alitalia had to give up four pairs of slots at Milan Linate as a condition of its approval, that did not satisfy Air One, which has been pursuing the case legally ever since.

In the latest twist, in early March an Italian appeals court agreed with Air One and ruled that a new tender must be held for Volare. But Volare, which includes charter carrier Air Europe and LCC Volareweb, has already been absorbed into Alitalia as its response to the challenge of the LCCs, and Volareweb is now expanding fast, with its current fleet of four A320s set to increase to 10 by the summer of 2008, most of which are likely to be A319s. It’s clear that if Air One loses out to Air France/KLM, then it will battle hard against expansion of Volareweb operations at Milan Malpensa — notwithstanding the recent court ruling, which may completely throw the future of Volare into doubt again.

The future?

If — as seems likely — the Italian government’s 49.9% stake is bought by Air France/KLM, the future for Alitalia will still remain uncertain. Most pressingly, the Air France bid has divided Alitalia staff, and the unions at Alitalia may react badly to the new owners of the flag carrier. Securing a deal with staff is the number one priority for Air France/KLM, and Spinetta has already met Alitalia unions, including the key UGL union, since if they cannot be persuaded of the merit of an Air France/KLM takeover then industrial action to prevent the cut–backs of routes and staff is inevitable.

But assuming a scenario of labour unrest doesn’t happen, a key problem for Alitalia/Air France/KLM will be what the competition does at Milan Malpensa as Alitalia reduces its presence at the airport. Air One is likely to pile into Malpensa if the flag carrier leaves the door open there, and just how many of the slots will be turned over to Alitalia’s charter or LCC operation remains to be seen: LCC subsidiary Volareweb is already starting to increase European routes out of Milan, but following the release of Alitalia’s summer schedule, slots Alitalia is no longer using at Malpensa have been released back to the airport operator — which is infuriating opponents of Alitalia’s strategy.

While Alitalia’s summer schedule is based around the Rome Fiumicino hub, even at Rome some routes have been closed (such as to Shanghai, Mumbai and Delhi on longhaul, and to Zagreb, Minsk, Lyon and Copenhagen in Europe), although frequency is being increased at certain other routes. From the summer Alitalia will operate to 83 destinations, of which 77 are served out of Rome, 38 from Milan Malpensa and 18 from Milan Linate.

More worrying perhaps for Alitalia is the spectre of Ryanair, which has ambitious plans for Milan Malpensa. The LCC is urging the airport to turn itself into a low–cost hub, and promises hundreds of millions of Euros of investment into Malpensa if the airport does so. Ryanair has long been keen to win more passengers within and to/from Italy, and in December 2007 Ryanair asked the European Commission to block Air France/KLM’s bid for Alitalia until both airlines pay back a total of €2.7bn in "illegal state aid" from the Italian and French governments (of which the Alitalia portion is €1.7bn).

If the Air France/KLM deal does go ahead, regional politicians in the north of Italy may well persuade the airport to open itself up to Air One or even Ryanair, and while this will secure local jobs, substantial competition out of Milan Malpensa would have unknown effects on Air France/KLM’s projections for Alitalia. The threat to Alitalia of Malpensa being opened up became even more likely once a small but key political partner left the centre–left government coalition in January, leaving Prodi without a working majority in the Italian senate. That development hit the share price of Alitalia in January and it fell by almost 10% on one day, prompting a brief suspension on the Milan market. As of early March the share price had dipped under €0.6, giving Alitalia a market cap of around €820m.

The election...

Alitalia insists the talks with Air France/KLM will not be affected by the uncertainty over the future of the Prodi government, but with a general election scheduled for April 13th and 14th, the political imperative has shifted. The centre–right parties are ahead in the opinion polls, and they are firmly opposed to Air France/KLM’s takeover.

Forza Italia — the largest centre–right wing party, led by Silvio Berlusconi — is very critical of the current situation, and may prefer Alitalia to go bankrupt and for a new national airline to be launched with new labour agreements.

Another right–wing party is the Northern League, which is fiercely opposed to Alitalia cutting back its presence at Milan Malpensa. AP Holdings/Air One’s hopes are therefore not yet dead even though a legal challenge launched in January by AP Holding against the government’s decision to allow exclusive negotiations between Alitalia and Air France/KLM was rejected by an Italian court in late February (although that decision is being appealed by AP).

Crucially (and slightly confusingly) in mid- February Air France/KLM said that while it will make a decision on whether to make a binding offer by mid–March (well before the Italian general election in mid–April) it added that it would only go ahead with the deal if the new Italian government approved the Franco–Dutch takeover, which might not happen if the centre–right coalition wins the election. In any case, while Air France/KLM has experience of going through a merger process before, and this is likely to make it aggressive in cutting back Alitalia into the shape it needs to fit into the new Alitalia/Air France/KLM giant, the advantages of the AP Holdings/Air One bid may have been underestimated by many analysts.

Crucially, under AP Holdings the airline would retain the goodwill of unions and politicians alike, and the changes that still need to be made at Alitalia could be carried out in a far less aggressive and much more achievable way by Italian owners than by Air France/KLM. With short–term financial and labour stability assured, an Air One–owned Alitalia would then be in a much stronger position to link up (even with equity) with one of Europe’s larger airlines — and preferably Lufthansa. The Air France/KLM bid may offer scale and kudos, but it may not necessarily be the best option in the long–term for Alitalia.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| Alitalia | |||

| A319 | 12 | ||

| A320 | 11 | ||

| A321 | 23 | ||

| 747-400 | 3 | ||

| 767-300ER | 12 | ||

| 777-200ER | 10 | ||

| MD-11F | 5 | ||

| MD-80 | 75 | ||

| Total | 148 | 0 | 3 |

| Alitalia Express | |||

| ATR-72 | 10 | ||

| ERJ-145 | 14 | 7 | |

| Emb-170 | 6 | 6 | |

| Total | 30 | 0 | 13 |