US LCCs: new market realities, new strategies

Feb/Mar 2007

In recent months LCCs in the US have announced or hinted at a host of new strategy initiatives. Florida–based LCC Spirit is going to start charging for all checked baggage and on board beverages Ryanair–style while slashing fares by up to 40%. Low–cost pioneer Southwest, which has been very conservative with revenue management in the past, is also considering charging extra fees. AirTran and Frontier have formed a unique ticket–booking and FFP partnership, while JetBlue has agreed in principle on such a tie–up with Aer Lingus and is in negotiations with other international carriers.

These are all examples of how US LCCs are focusing on revenue generation, or trying out new revenue strategies, as their cost advantage over the legacy carriers erodes and competitive pressures mount. The interesting question is: To what extent will the business models change?

For the second year running, US LCCs no longer stood out from the crowd in terms of profitability in 2006. Although Southwest was still in the lead with a 10.7% operating margin, most other airlines were in the 2–5% range. JetBlue and US Airways, with margins of 5.4% and 5.1%, performed slightly better than AMR and Continental (4.7% and 3.8%), but AirTran only achieved a 2.2% margin and Frontier a negative 0.6%.

LCC–legacy unit cost differentials, while still significant, have lessened as a result of the network carriers' successful cost cutting and the Chapter 11 restructurings. Since LCCs are lean organisations, they have not been able to match the cost cuts. AirTran may be the only exception, in that the growing mix of the larger 737–700s in its fleet, which until 2004 included only 717s, has facilitated a strong and steady decline in ex–fuel unit costs (see AirTran briefing, page 16).

As a result, LCCs have been hit hard by the past two years' hike in fuel prices. They now have to deal with a reinvigorated legacy sector. And they did not get a chance to acquire needed additional slots, gates and assets this year, because the legacy M&A process never got started.

Add to that a host of potential negatives in 2007 — a slowing domestic economy, tougher unit revenue comparisons and a less favourable domestic capacity environment — and it is not a surprise that the LCCs have suddenly focused on revenue–generation and are ready to experiment with new strategies. That said, even the LCCs continue to find modest additional cost savings. It typically involves squeezing a little extra productivity from the workforce; for example, Southwest has continued to see a decline in employees per aircraft.

This year’s revenue–boosting efforts seem focused on two areas: expanding through alliances and growing new types of ancillary revenues. In addition, JetBlue is looking at new ways to retain the highest–yield traffic, such as providing a "first class" section on aircraft.

Alliances: There appear to be two motives behind the LCCs' alliance–building: to "de–regionalise" operations (a term used by Frontier), as in the case of Frontier and AirTran, or to leverage a strong hub position to maximise revenues, as in the case of JetBlue.

AirTran and Frontier broke new ground in November 2006 by launching a referral and FFP partnership — the first of its kind between LCCs in the US. Instead of code–sharing, the airlines "refer" passengers to each other via their websites and call centres, and passengers can earn and redeem frequent–flyer miles on either carrier.

The deal links AirTran’s strong East Coast network with Frontier’s western US network, giving each airline access to regions where they are weak. It enables the airlines to diversify away from unusually competitive hub situations — AirTran shares its Atlanta hub with Delta and Frontier its Denver hub with United and Southwest. Frontier is one of the worst–performing US LCCs (and on the "sell" lists of many analysts, though its liquidity position remains adequate) because of its nightmarish competitive and revenue environment, with three carriers all adding significant capacity at Denver.

Frontier said recently that the AirTran alliance had met expectations and could boost its revenues by $5–6m annually. But the airline is obviously working on a number of fronts — it has set up a new feeder subsidiary (Lynx Aviation), forged new RJ feeder contracts with regional partners and expanded to Mexico and Canada. It is also open to additional LCC alliances.

JetBlue, by contrast, is in a strong position at its JFK hub, where it accounts for over 50% of the domestic traffic. It has ample room to grow there after its new terminal opens in late 2008. The airline wants to leverage that strength to unlock new revenue sources, such as international code–shares, and has been talking to potential partners since at least mid–2006.

The first of those deals is likely to be with Aer Lingus. It was reported in February that JetBlue and Ireland’s second largest carrier had "agreed in principle" to a ticket–booking alliance, to be implemented this summer. The deal would link the carriers' websites, enabling customers to book seats between Ireland and 51 US destinations in one go, but it would not include code–sharing. Aer Lingus, which has left the OneWorld alliance as it pursues a low–cost strategy, operates daily flights to JFK from Dublin and Shannon and to Boston from Dublin.

Some have questioned the wisdom of sending loyal customers to an airline that comes nowhere near to matching JetBlue’s service quality. But JetBlue is expected to forge similar deals with a number of international carriers, and perhaps it will find more equal partners in the larger markets, such as Virgin Atlantic on the UK–US routes (if Virgin America does not start operations). Separately, JetBlue announced a marketing partnership with Cape Air to improve feed to its Boston focus city.

In the past, LCCs shunned alliances because the idea was contrary to the low–cost model in that it tended to increase complexity, but technological developments have changed things. Southwest made that point when launching its pioneering code–shares with ATA two years ago (the motive there was to obtain gates at Chicago Midway).

The common theme for the latest LCC alliances is that they are all low–complexity, low cost undertakings, relying on new technology. JetBlue has described the concept as "interline lite" — something that can be accomplished without significant alterations to the business model.

Ancillary revenues: Southwest pioneered the low–cost, no–frills formula for LCCs everywhere but over the years the model has evolved in different directions on the opposite sides of the Atlantic. In the US, LCCs have added frills and included services such as checked baggage, snacks and drinks, entertainment systems and advance seat assignments in the air ticket price, with the emphasis being on providing value (good service at a fair price). In Europe and elsewhere, LCCs have retained the original no–frills concept, started offering ultra–low fares and introduced extra fees for services such as checked baggage.

However, in recent years US LCCs have developed ancillary activities such as frequent–flyer programmes, co–branded credit cards and vacation packages. JetBlue, for example, has profitable partnerships with American Express, DirecTV, XM Radio and Dunkin' Donuts, as well as JetBlue Getaways. In contrast, not even large European LCCs such as Ryanair have FFPs.

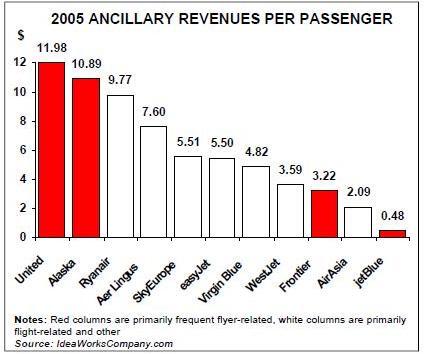

These regional differences were highlighted by IdeaWorks, a Wisconsin–based brand and marketing consulting company, in an October 2006 analysis of airline ancillary revenues. Although the analysis showed that the non–US a la carte strategies produced more ancillary revenue per passenger than the US LCCs' relatively young FFPs (see chart, above), IdeaWorks felt that FFPs offered greater revenue potential, in addition to making consumers more loyal to a brand. The conclusion was that "exceptional financial results are likely to be realised by those airlines that master the magic of combining the best features of the European and US models".

The Ryanair–style "unbundling" strategy is not entirely new in the US. Allegiant Air, a Las Vegas–based niche carrier, has used the strategy very successfully for several years in leisure markets linking small cities with popular tourist destinations. The model has worked because it has been important to be able to market the lowest possible fares and because there is little direct competition (see Allegiant briefing, Aviation Strategy Jan/Feb 2007).

Spirit, which has hubs at Detroit and Ft. Lauderdale and serves 33 cities domestically and in Latin America and the Caribbean, is now taking a major leap towards becoming the second Ryanair–style LCC in the US. In June, the carrier will start charging $5 each for the first two checked bags (or $10 each if not booked via the website), $100 for the third bag and $1 for beverages. Currently, the first checked bag and beverages are free. Spirit is also cutting fares by 10% to 40% and experimenting with Ryanairstyle "one–cent, plus fees and taxes" fares in some markets in March–May. Spirit also plans to eliminate first class service but will continue to sell what will be known as "Big Front Seats" at premium prices.

That may well be a good strategy for Spirit because, like Allegiant, it is very leisure–oriented. It may lose higher–yield passengers domestically but could gain traffic in Latin America and the Caribbean, where much of its growth focuses.

But why is Southwest suddenly considering charging extra fees? The main reason is that, as a result of its weakening fuel hedges, Southwest has what one analyst called a "$300m–plus fuel hurdle" that must be overcome in 2007, for the company to have any chance of reaching its 15% earnings growth target again this year. The domestic economy may be slowing, so the airline feels that it would be "foolish to get addicted to fare increases" and that it might be best to find other ways to increase revenues.

CEO Gary Kelly also explained recently that now that it carries more domestic passengers than any other airline, Southwest is looking to leverage that strength and "could get more aggressive with revenue management, such as charging extra fees". The airline has always had extremely conservative revenue management. It has low walk–up everyday fares, no change fees, minimal code–sharing, minimal ancillary revenues and modest cargo revenues. Its fare increases have always been gradual and modest. Consequently, the airline feels that there a many potential revenue opportunities.

However, Southwest is only considering a few options and is thinking about it strategically — what could be brought online this year, what in 2008 and what in 2009, while retaining a high–quality product and position as the dominant LCC. The airline noted that there are improvements in technological capability in the pipeline that will give it more flexibility to pursue new options.

Product upgrades: JetBlue, which over the past year has put much effort into improving yield management but also expects to cut costs by $120m in 2007, has found an interesting way to woo the highest–paying customers without making anything worse for other passengers or incurring extra expenses. The airline has removed a row of seats from its A320s, reducing the seating from 156 to 150, which enables it to operate the aircraft with two (rather than three) flight attendants. This will save about $30m annually, but the loss of ticket revenue from those seats will be greater. But after the reconfiguration seats in the first 11 rows (44% of total seats) will have an industry–leading 36–inch pitch, while the remaining seats will have at least 34–inch pitch. JetBlue plans to reserve some of those front seats for last–minute or first–class type customers that would not normally fly the airline and will be "rolling out some exciting programmes" that are expected to boost revenues.