Air France-KLM: building the twin hub strategy

Feb/Mar 2006

Following the merger of Air France and KLM in May 2004, the France–KLM group is today the largest airline in the world, with 100,000 employees and a fleet of more than 500 aircraft that operates to 234 domestic and international destinations. Can the group’s strategy of two separate brands, two largely separate managements and workforces, and twin hubs at CDG and Schiphol be successful in the long–term?

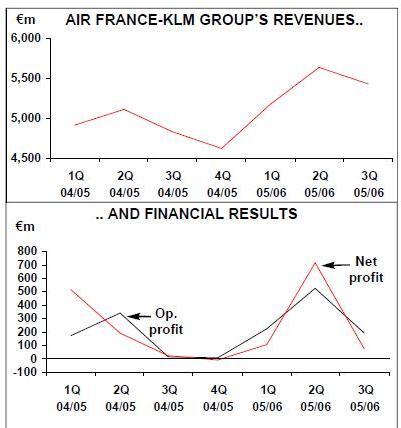

The financial results since Air France and KLM came together have been encouraging (see graphs, below). In its first year of merged operations (the financial year to end of March 2005), Air France–KLM recorded an operating profit of €489m (compared with €405m in 2003/04 on a comparable basis) and net profits of €351m (compared with €292m in the previous financial year), based on a 7% increase in revenue to €19.1bn and a 5.7% rise in passengers carried, to 64m.

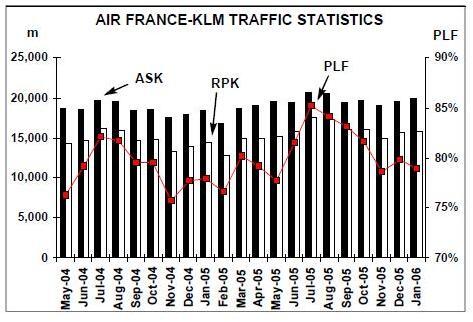

And in first three–quarters of the 2005/06 financial year (April–December 2005), Air France–KLM saw operating profit shoot up 77% to €940m compared with the same period in 2004/05, thanks largely to a rise in passengers and cargo carried. In April–December 2005 passengers carried rose by 5.8%, with a 5.8% rise in a capacity outstripped by an 8.8% rise in RPKs, leading to a 2.2% rise in load factor to 81.3%. In the same nine–month period cargo traffic rose by 2.7% and cargo turnover by 11.4% to €2.2bn — Air France is the second largest cargo operator in Europe, after Lufthansa.

Air France–KLM’s turnover for the nine–month period increased 9.4% to €14.9bn, and net income rose 23.9% to €731m. However, fuel costs rose 27% in the third quarter (to €1bn), resulting in an operating cost increase of 8.9% in the same period (excluding fuel, operating costs rose by just 5.3%), although the impact of fuel price rises was offset somewhat by hedging and fuel surcharges, which increased again in September 2005, by another €6 for long–haul flights, €2 for medium–haul and €1 for domestic. Nevertheless, Air France–KLM’s improved performance was seen as slightly disappointing by some analysts, who had expected an even stronger set of results. One analyst said he had expected a better result as the 2005/06 year was likely to be a "cyclical peak" for the European aviation industry.

That viewpoint is a little harsh, and although January–March is traditionally Air France–KLM’s weakest quarter, for the full financial year to end of March 2006 Air France–KLM expects to report an operating income of more than €900m. This implies an operating loss for the January–March 2006 period — whereas Air France–KLM reported an operating profit of €9m in January–March 2005 — but overall, an operating profit of close to €1bn for the full year is still impressive Air France–KLM has been particularly effective in hedging its fuel costs. As at mid- February, Air–France–KLM had hedged 84% of its fuel needs for the current financial year (2005/06) at $39 per barrel, and at the same date had hedged 62% of its fuel needs for 2006/07 at a price of approximately $47 per barrel, and 34% of its needs for 2007/08 at $50 per barrel. That is better than BA is doing, as at the same date the British flag carrier had hedged 81% of 2005/06 at $45 and 50% of 2006/07 at $55, and even better than Ryanair, which had hedged 90% of 2005/06 needs at $49. But, as group chairman and CEO Jean- Cyril Spinetta admits, "at the end of the day — probably in 2008 — we’ll be paying the market price for our fuel as the effect of our hedging policy decreases over time … The only solution is to reduce our costs."

Cost cutting

Since the merger, the group has adopted a variety of cost–cutting measures, including joint purchasing, the integration of country operations, rationalisation of maintenance, the adoption of a joint FFP (Flying Blue), combined corporate sales and joint IT systems (although this latter project will take up to five years to complete).

This cost cutting appears to be going well, and since 2004 Air France–KLM has steadily raised its estimate of synergies from the merger. The latest forecast is for cumulative synergies of €610m by the end of the 2008/09 financial year, up 22% from the original estimate.

This breaks down into €180m from revenue management, €98m from commercial synergies, €97m from network savings, €76m from maintenance, €73m from IT, €50m from cargo and €36m from all other synergies.

These synergies come on top of continuing cost cutting programmes at both airlines. KLM saved €520m in costs during the 2004/05 financial year, mainly through cutting 4,500 jobs, using more efficient aircraft and through the elimination of commission for travel agents. At Air France, the so–called "Performance" cost–cutting plan ended in March 2004, having achieved savings of €300m per year. In its place is the "Major Competitiveness 2007" programme, which aims to cut another €800m in costs a year by the 2006/07 financial year. Measures here include outsourcing the airline’s entire lost baggage handling service (partly in order to save costs and partly to mitigate the risk of the EU’s tougher compensation regulations) and the increased outsourcing of ground handling (for example, 11 airports were outsourced last year to Swissport, which the airline says will give it "tangible cost savings").

As part of this ongoing effort, last January Air France unveiled a new three–year plan for its 35,000 ground staff, in which geographical and functional mobility of staff is encouraged in the light of the increasing use of self check–in terminals and online check–in. In 2005, 250 ground staff retrained to become flight attendants, and in the future half of all flight attendants will be hired from existing ground staff.

Following the presentation of the plan, CGT — the giant French trade union — said it suspected that Air France was planning to trim between 3,000 and 5,000 positions from the current workforce of 71,600 by not replacing staff retirements from now until 2008.

In February Air France denied the claim, saying that the workforce would remain "stable" at its current level until the end of the 2008/09 financial year, and that in any case productivity per employee had risen by 21% in the four years to end of September 2005.

Nevertheless, unions are worried about the spread of e–ticketing and Air–France KLM’s target of eliminating paper tickets by 2007.

Currently 70% of domestic passengers and 54% of international passengers "opt" for e–tickets, but the group will accelerate the take up by imposing a €15 surcharge for each paper ticket issued, to be introduced some time this year.

Despite this, relations between unions and management appear reasonably good, even though union members at Air France joined the general strikes in France last year to protest at the government’s economic policies (and which are continuing with another day of action in March). The relationship will be bolstered by a €500 bonus Air France is expected to give to each of its employees for the 2005/06 financial year. Unions protested vehemently last year after the airline only awarded staff a bonus of €45 for 2004/05 while at the same time giving senior management substantial increases in salary.Management has learnt a lesson from that, although the bonus is likely to cause trouble elsewhere in the group as it applies only to Air France workers, and not to those employed by KLM. In February Air France–KLM also announced it was setting up a pan–European works council, or "employee representatives committee" with a rather unwieldy membership of 37, drawn from across Europe and with each member appointed or elected for four–year terms.

Overall, although the merger of Air France and KLM is giving synergies and the two airlines are continuing to cut costs, essentially the group’s core strategy going forward is centred around growth and the winning of market share from competitors, particularly European ones. Spinetta says: "In the past, many mergers have failed because they have concentrated too much on cost–cutting and downsizing and not enough on growing market share and revenues. Right from the beginning, we decided on an offensive rather than defensive strategy — although some industry analysts were disappointed when we decided not to cut back on capacity and staff. But giving up slots and reducing capacity at airports with restricted capacity following a merger would be a great strategic mistake."

Fleet

The base for this growth strategy is the group’s massive fleet. Air France currently operates 253 aircraft (see table, opposite) with 35 aircraft on firm order — 11 A320 family aircraft, 10 A380s and 14 777s. The A320 family aircraft are replacing Air France’s fleet of 737- 500s, while the long–haul fleet will be boosted by nine 777–300ERs and 10 A380s, although the latter’s introduction is being delayed for a year, with the first flight now scheduled for April 2008.

"Half the blame" for the A380 delay is due to Airbus, says Air France–KLM, and the other half belong to the Franco–Dutch group itself, as although aircraft will be ready for delivery from October 2007, this is a traditionally a period of low demand for the Air France, and instead it preferred to receive the first aircraft in time for the summer 2008 season, when they will be used initially on routes to China and Japan.

For cargo Air France operates a fleet of seven 747–200Fs and five 747–400ERFs. The 747–200Fs are being phased out and will be replaced partly by five 777–200LRFs that will be delivered from autumn 2008 onwards and partly by three 747–400SFs that are being converted from passenger aircraft from 2007 onwards.

KLM operates 104 aircraft and has 14 aircraft on order. All but one of the orders are for long–haul models, with five outstanding A330- 200s due to arrive by March 2007 as part replacement for KLM’s fleet of 767–300ERs.

Air France–KLM also has more than 170 aircraft in four subsidiary airlines — the largest regional aircraft network in Europe — and the group is expected to place a large order for up to 100 replacement aircraft within the next few years. At this stage the only potential rival to an Embraer 170/190 order appears to be the proposed Russian Regional Jet and the Bombardier CSeries. Air France’s Régional subsidiary — which serves 45 destinations with a fleet of 66 aircraft, the majority of them being Embraer — is also receiving six 100–seat Embraer 190LRs from the first quarter of 2007.

Twin hub focus

Ever since starting its development of CDG as a hub in 1996 (which the airline admits was five years too late), Air France has concentrated primarily on improving frequency on connecting routes into the hub (the average number of weekly frequencies per route is up 82% in 2005 compared with 1996) over rises in capacity (seat capacity is up by 46% over the same period). Now however, Air France believes that its density of connections into CDG is sufficiently developed, and so over the next few years it will concentrate on boosting capacity on the existing medium–haul feeder routes.

CDG is set up with six waves of arrivals and departures a day, and in 2004/05 Air France had around 18,000 weekly connections (both ways) at CDG , defined by Air France as less than a two–hour gap between an arriving medium–haul and departing short–haul flight. This compares with 6,700 weekly connections for KLM at Schiphol, 12,000 for Lufthansa at Frankfurt and 6,600 for BA at Heathrow. For CDG, that translates into approximately 24,000–25,000 passengers arriving at the airport each day on one Air France flight and departing on another one.

In 2004/05, this represented 52.9% of all Air France passengers each day at CDG — although, interestingly, this number has been flat for three years, not improving since a fall from the 58% figure that Air France recorded in 2001/02. Air France says the step fall in 2002/03 (to 52.7%) was due to Iraq, SARS, a depressed economic environment and air traffic controller strikes, but it offers no explanation for why the airline has not regained this level over the last three years.

Air France believes that percentage will be improved by infrastructure developments at CDG, which is one of the few hubs in Europe that has room for expansion. Feed comes into CDG from regional subsidiaries Brit Air, Régional and Irish carrier CityJet (which between them connect to more than 20 European destinations), and Air France has recently agreed to rent its own regional terminal (to be named 2G) at CDG for a 19–year period from 2008. The deal with Aeroports de Paris (ADP) will cost Air France–KLM an upfront fee of €89m, and the move comes despite criticism from Air France over the government’s decision to approve ADP’s proposed increase in fees at CDG by 5% a year until 2010. The group believes that exclusive access to a terminal that will be able to handle 20 regional aircraft at any one time (equating to 3m passengers a year) will help it develop much better feed for its long–haul flights. Air France–KLM had contemplated buying a minority stake in ADP (as Lufthansa did with Fraport), but has now decided that directly funding the terminal it needs would be a better use of its money. This policy may extend to an Air France investment in new satellite S3, which is due to open in 2007 in order to handle A380 operations.

Feed also comes into CDG via the TGV high speed rail network (via a station at CDG) and a strong regional train network through SNCF. On the other hand, the Eurostar train service has eaten into what was previously a lucrative Paris–London market. Eurostar now has a 71% share of passengers on the route, compared with 10%- 12% for both Air France and British Airways, and apparently Air France only continues London–Paris flights in order to pick up connecting business passengers that resolutely refuse to take the delay–prone Eurostar. Altogether, connecting passengers account for more than a third of all Air France’s passengers coming from the UK.

For Air France, dominating CDG is key to its strategy. Connecting passengers represent 56% of all passengers on Air France’s long–haul flights to North America, rising to 63% for routes to Asia, and those connecting passengers come not just from France, but from all over Europe. An analysis of Air France’s connecting passengers at CDG shows that only 24% live in France — 40% are from other European countries, 24% from North and South America, 7% from Asia and 5% from Africa/the Middle East. And 31% of connecting passengers are classified as senior managers (defined as director level of a company), which is why Air France believe its medium–haul mainline feed must keep a business class product.

Following the merger, initial route and service restructuring between Air France and KLM took place through 2004 and 2005, but the "final" overhaul and co–ordination of the two airlines' timetables will take effect this summer. In particular, flight arrivals and departures from the "non–country" airline partner are being adjusted to optimise connection times with long–haul flights out of CDG and Schiphol. However, the twin hub strategy is not about each hub specialising in routes to certain parts of the world, with the group eliminating overlapping routes to the same destinations.

Instead, Spinetta insists each hub is being built up on its own merits, maximising incoming feed from both Air France and KLM. What the group will not do is "develop one at the expense of the other", says Air France- KLM — which reflects the political realities behind Europe’s first merger of flag–carriers.

Air France–KLM argues that the long–haul networks of the airline are complementary, and indeed — as of the summer 2005 season — of 111 long–haul destinations offered by Air France and KLM, just 32 were served by both airlines, with the figure for medium–haul being 45 out of 126. Inevitably there will be some rationalisation of the network (long–haul destinations with moderate demand will only be served by one of the group’s two airlines) but, as Air France puts it, there will be no "sawing off branches". Instead the group is encouraging "fluidity" between the networks via combinable fares that allowing outbound flights on one carrier and inbound on the other. The group is building feed from France and elsewhere into Schiphol — for example, wholly owned Air France subsidiary Régional launched a Strasbourg–Schiphol route in October 2005. As a result, in 2005 Air France- KLM passengers carried through Schiphol rose 5.4% to 27.4m, representing 62% of all passengers at Schiphol last year. That proportion is increasing, as Air France–KLM passenger growth at Schiphol is rising faster than Schiphol overall passenger growth (3.8% in 2005). KLM hopes to repeat the trend through a 5% increase in capacity this summer, mostly via extra frequencies on existing routes, although some routes are being dropped, such as Amsterdam–Tbilisi. This summer KLM is also realigning its economy product to that of Air France’s, including the introduction of in–flight wine and beer.

According to Air France–KLM, the double hub strategy, with feed coming in from more than 150 European destinations, will result in additional revenue of around €60m in 2005/06, and this figure is expected to rise to almost €100m in 2008/09.

Long-haul

The other side of Air France–KLM’s twin hub strategy is the building of an even stronger long–haul network out of CDG and Schiphol to the Americas, Asia, Africa and the Middle East, to which Air France and KLM currently serve 112 destinations. In the winter of 2005/06 capacity grew by 6.4% at Air France- KLM, focused mostly on routes to Latin America (up by 25%) and Asia (up by 13%), and this summer group capacity is rising by 5.6% compared with a year ago. The summer increase is coming largely through increased frequencies and the use of aircraft with greater capacity, with a 6% rise coming on long–haul routes (with Asia up 11%, Africa 11% and the Middle East 20%). In comparison, mediumhaul capacity is rising this summer by 6.3% (with new routes to Yerevan, Leipzig and Katowice), while domestic capacity will grow by just 1%.

Spinetta says that the group’s annual revenue growth target is 5%-6% for the next five years, based on capacity increases of 4%-5% per annum, but with long–haul the focus of growth, with 5% growth in capacity each year until the end of the decade, compared with 2%-3% p.a. at medium–haul. Up to 2010 particularly strong annual growth rates are planned for Latin America and the Middle East (both 8%) and Asia excluding Japan (7%).

Most of this increase will come from higher capacity aircraft such as the 777–300 and thA380, which will replace long–haul aircraft that are currently experiencing load factors approaching the mid–80s. The introduction of larger aircraft and the "efficiency of our connecting hubs" will also cut units costs on longhaul by 3.5% by 2010, the group estimates. Among the specific long–haul markets targeted is China, to which the group currently operates just four routes, with a Schiphol- Chengdu route being added by KLM in May. Air France and China Southern (which is joining SkyTeam later this year) currently code–share between CDG and Guangzhou and the two airlines are keen to extend their relationship, perhaps even to a joint venture based on cost and revenue sharing between the two countries. Air France–KLM would also like to operate a route direct between Schiphol and Taipei (without having to stop at Bangkok, as KLM does at present) but to do that it needs to overflow China, and the group will apply for permission soon.

Another area targeted for growth is India, and Air France plans to increase capacity there by 20%-25% a year for the next three years. Air France currently operates 29 flights a week (a tripling of capacity in less than two years), to New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad and Bangalore but will increase frequency, add new routes and increase code–sharing.

The Bangalore route was launched in November 2005 but already has a load factor of more than 90%. Much of the demand for Air France’s flights from India is for connecting traffic onto other European destinations, Africa and North America. If passenger growth is maintained Air France will analyse operating A380s into Delhi or Bombay from 2010. Elsewhere on long–haul, in December 2005 Air France agreed a joint hub deal with TAM to allow Air France passengers onward connections throughout the continent from Sao Paolo and Rio de Janeiro, while in October 2005 KLM started an all business class service between Schiphol and Houston in partnership with Swiss–based PrivatAir (which provides similar services for Lufthansa), taking advantage of increasing demand for business class by oil company executives.

In terms of product, this winter season Air France has axed first class on all long–haul aircraft others than 777s, with the premium product remaining only on routes to selected Asian and North American destinations such as Tokyo, Singapore and Hong King. All A330, A340 and 747 aircraft will instead now have economy and the new business class launched last year, which includes a telephone and flat bed, and which with development and fitting will cost Air France around €300m.

This product improvement is vital for Air France–KLM as senior Air France managers are becoming increasingly concerned at proposed long–haul capacity increases from competitors, particularly from Emirates. Air France estimates that if it was able to benefit from the same fees and charges in Paris that Emirates does at Dubai, it would improve its operating income by more than €800m, but the key fear is that the planned long–haul capacity increases from Emirates will depress fares and yield for everyone on routes from Europe to Asia.

Air France is also beginning to realise that long haul markets may be as price sensitive as short–haul — when Air France reduced its return fares on one route to North America route by just €14, it immediately gained 10% in market share.

LCC challenge

While Air France–KLM is concerned at potential competition in long–haul, the group appears much less worried about the threat from LCCs. That appears dangerous given the steady steps that both easyJet and Ryanair have made into the French market. easyJet is already the second largest airline in France, carrying some 5m passengers a year out of Paris and in total offering 39 routes from Paris CDG (nine routes, with Lisbon starting on March 1st), Paris Orly (10, with Rome Ciampino being added in April), Nice (13), Grenoble (three), Toulouse (two), Lyon (one), and Marseilles (one, with Liverpool launching in April).

Ryanair has 47 routes out of France, from Paris Beauvais (nine routes), Carcassonne (five), Nantes (four), Nimes (four), Limoges (three), Bergerac (three), Biarritz (two), Marseille Provence (two), La Rochelle (two),Dinard (two), Montpellier (two), and one route from each of Brest, Tours, Poitiers, Rodez, Perpignan, Toulon, St. Etienne, Grenoble and Pau.

Both easyJet and Ryanair are believed to be talking with Lyon–Saint Exupéry airport about setting up an operational base there centred on a new, dedicated LCC terminal with capacity of between 1.2m–1.8m passengers each year. This would be a major challenge to Air France–KLM as Lyon is its second most important French hub, out of which it carries 3.2m passengers each year. The airport’s owner, the Lyon chamber of commerce, is apparently offering to convert a charter departure building into a "basic" terminal for LCCs with fees per passenger of around €1.50, compared with €7.95 levied to Air France–KLM passengers at the existing terminal. easyJet currently operates 17 flights week out of Lyon to Stansted, but it carries 2.1m passengers a year out of nearby Nice airport, and would look to build up a similar level of business out of Lyon if it agreed a suitable deal.

Naturally Air France is complaining bitterly about the proposed terminal, and has filed a legal case not only against Lyon’s low–cost terminal but also against similar plans at both Geneva and Marseilles airports. In October 2005 Spinetta said that LCCs were obtaining airport facilities at much lower price than Air France–KLM even though "runways and control towers" were paid for by other airlines (such as Air France).

This is nothing more than a normal competitive reaction by Air France–KLM, but the group’s only other response to the LCCs appears to be ongoing cost cutting and a (somewhat reluctant) dropping of fares where necessary. For example, in November and December 2005 Air France offered 4m seats for flights in 2006 at promotional fares up to 72% lower than normal (domestic routes were available from €89 return and Europe flights from €139 return).

When pressed on the point, the response from Air France–KLM’s management is that as long as the group keeps building its long–haul business, the impact of the LCCs will be minimal. Air France considers that LCCs have a totally different business model, and its calculations show that 65% of the difference in unit costs are due to two factors: denser seat configurations and better aircraft utilisation. In these areas — according to Air France — a "typical LCC" is 15% and 24% cheaper respectively (in terms of unit cost) than Air France. But Air France believes these differences are "acceptable", as its lower aircraft utilisation is inevitable due to the peaks of CDG, while lower seat density per aircraft is a result of business seats that are essential for securing feed into long–haul flights out of CDG. In other areas — particularly distribution (only 9% of ticket sales to the French market come via the Air France website, for example) — Air France is working hard to reduce its costs down to an LCC’s level, but as a whole Air France believes it would be a mistake strategically to be drawn into a bitter product, cost and fare battle with LCCs on point–to–point markets.

Instead, Air France prefers to concentrate on its hub strategy. Spinetta quotes a figure from a 2005 study by the Boston Consulting Group that on long–haul flights out of Europe, connecting passengers accounted for 70m out of a total of 125m passengers in 2003, and that in 2013 connecting passengers will account for 115m out of 215m passengers.

Although the proportion of connecting passengers falls over this period (from 56% to 53%), Air France–KLM is basing its strategy on the fact that in absolute terms there will always be a huge market for connecting passengers, and that in CDG and (to a lesser extent) Schiphol, Air France–KLM has key assets in securing this connecting business.

The future

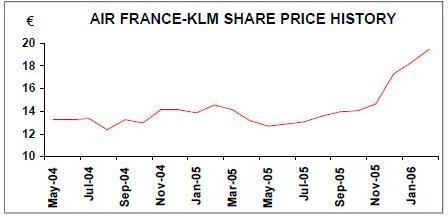

For the moment, Air–France–KLM’s strategy seems to be working. On release of March- December 2005 results (in mid–February), Air France–KLM’s share price rose to more than €20 — its highest level since the group was formed in May 2004 (see graph, opposite). Results for the financial year to end of March are released in May, and barring the unexpected, the group will reveal a record profit margin.

Importantly, Air France–KLM’s cash position stood at a relatively healthy €4.3bn as at the end of 2005, compared with €3.1bn a year earlier, with €817m of the increase in cash coming from the sale of 23.4% of global distribution system Amadeus. More importantly, net debt fell by €1.1bn in the first nine months of 2005/06, to stand at €4.5bn as at 31 December 2005.

That’s not to say everything is going according to plan. In January, after continuing opposition from the US Justice Department, Air France–KLM, Delta and Northwest admitted defeat in their exhaustive efforts (which were initiated back in 2001) to secure antitrust immunity from the US for their SkyTeam alliance. Air France–KLM now claims that the existing bilateral agreements between Air France and Delta, and between KLM and Northwest, will continue irrespective of antitrust immunity, and that code–sharing and other permissible links between the airlines will produce around 70% of the benefits they would have gained if antitrust immunity had been secured.

But there’s no doubt that the failure to win immunity is a setback for Air France–KLM, and the inability to harmonise both fares and timetables across the SkyTeam members (particularly between Delta and Northwest) will cut many millions of euros from revenues at the respective airlines.

In any case, Delta and Northwest both went into Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in September 2005 and while Air–France KLM says this does not impact upon the Franco- Dutch group, at the very least the moves signify that Air France–KLM’s SkyTeam partners are in no position to grow and become major players in the global aviation industry — let alone within the SkyTeam alliance — even though Delta, for example, wants to focus on the transatlantic market. A Northwest–Delta merger may be the best result for Air France–KLM in the long term.

With transatlantic moves blocked, speculation will inevitably grow on potential equity deals this side of the Atlantic, or even further afield. Thanks to historical strategic and political reasons, Air France currently has an eclectic portfolio that includes, among others, stakes in Air Caledonie (2%), Air Madagascar (3%), Air Mauritius (3%), All Africa Airways (51%), Air Tahiti (7.5%), Austrian Airlines (1.5%), Cameroon Airlines (3.5%), CCM Airlines (12%), Royal Air Maroc (3%) and Tunisair (5.5%).

At the start of the year the press speculated on a possible bid by Air France for Alitalia, after it invested €20m to maintain the 2% stake in the Italian flag carrier that it has held since 2002 (see Aviation Strategy, January/February 2006). Air France denied the bid rumours, and it makes little sense for Air France to get entangled with the mess of Alitalia. Among the other airlines Air France has been linked with in terms of an equity stake are THY (the airline is supposedly in negotiations to buy 51% from the Turkish state), and Garuda — both of which have been dismissed by Air France–KLM.

Air France–KLM will probably steer clear of risky investments and instead concentrate on a declared strategy that is clear, consistent and which — for the moment at least — appears to be working. Analysts are prepared to give group management the benefit of the doubt over its assessment of the threat from LCCs, but nevertheless Air France–KLM must continue to drive down costs where possible. Excluding currency fluctuations, Air France has kept its cost per ASK in the Euro–cent 6.5 to 7 range for the last seven or eight years, and unit cost would be lower by at least 10% over that period if oil costs are stripped out. While this is not as good as the LCCs it’s a fair performance, although there is no room for complacency in the drive to cut costs.

The main uncertainty in the short–term may be a change in top management. Spinetta is contracted until 2010, but French sources suggest he may step down before then for "personal reasons".

| Fleet | Orders | |

| Air France | ||

| A318 | 11 | 7 |

| A319 | 44 | 2 |

| A320 | 67 | |

| A321 | 13 | 2 |

| A330 | 16 | |

| A340 | 20 | |

| A380 | ||

| 737-500 | 13 | |

| 747-200B | 3 | |

| 747-200F | 7 | |

| 747-300C | 2 | |

| 747-400 | 10 | |

| 747-400C | 6 | |

| 747-400ERF | 5 | |

| 777-200ER | 25 | |

| 777-200LRF | 5 | |

| 777-300ER | 11 | 9 |

| Total | 253 | 35 |

| KLM | ||

| A330 | 3 | 5 |

| 737-300 | 14 | |

| 737-400 | 13 | |

| 737-800 | 15 | 1 |

| 737-900 | 5 | |

| 747-400 | 5 | |

| 747-400C | 17 | |

| 747-400ERF | 3 | 1 |

| 767-300ER | 9 | |

| 777-200ER | 10 | 7 |

| MD-11 | 10 | |

| Total | 104 | 14 |

| GROUP TOTAL | 357 | 49 |

| Note: Excludes regional subsidiaries | ||