Copa: creating that Latin American buzz

Feb/Mar 2006

Panama’s Copa (Compania Panamena de Aviacion) made its debut on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in mid–December, following decisions by its 49%-owner Continental and Panamanian shareholders to monetise part of their stakes via a public offering.

The IPO, which made Copa the third Latin American airline (after LAN and Gol) to trade in the US, generated considerable investor interest and was priced above expectations. The stock surged in the subsequent weeks, valuing Copa virtually on a par with the world’s most successful LCCs. Since early January the share price has fallen to a more realistic level as several Wall Street analysts called the company overvalued in their initiation reports. Notably, UBS launched coverage of Copa on January 6 with a "reduce" recommendation (before upgrading the stock to "neutral" two weeks later).

JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch — three of the five underwriters on the IPO — initiated coverage of Copa on January 24, followed by Calyon Securities on March 3.

Analysts have been somewhat divided on how Copa should be valued and what its longer–term prospects are. Merrill and Calyon, which have "buy"/"add" recommendations on the stock, have stressed the airline’s numerous positive attributes and the fact that it is now trading at discounts to Latin American airlines and North American LCCs. (Merrill calculated those discounts at 20% and 40% respectively, on a 2006 P/E basis, or 5% and 10% on an Enterprise Value/EBITDAR basis.)

But JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley and UBS, which have "neutral" ratings on the stock, have expressed more concern about potential risks. JP Morgan also pointed out that when an adjustment is made for the airline’s unusually low tax rate, on an Enterprise Value/EBITDAR basis Copa trades "directly alongside proven heavyweights Gol, Southwest and Ryanair". Because of its unique circumstances, unusual business model and relatively low profile before the IPO, Copa is probably less well understood in international investor circles than other Latin American carriers were when they went public.

It has been helpful to hear Copa’s top executives tackle directly some of the issues at recent investor conferences. CFO Victor Vial gave a presentation at Raymond James' growth airlines conference in New York in January, while CEO Pedro Heilbron spoke at JP Morgan’s aviation conference in late February.

In the first place, Copa created buzz because the Latin American airline sector is hot. Large untapped markets with huge growth potential within the region, the progress made by key economies, success stories like LAN and Gol, and the rising LCC phenomenon in the largest countries have all helped catch the attention of international investors.

Panama is a very small country, but its strategic location, special international status and strong and stable dollar–based economy have enabled Copa to develop its home base into the "Hub of the Americas". Some investors may have seen it as a safe way to participate in the rapidly growing Latin American airline industry.

Although Copa is not an LCC (it is 100% hub–and–spoke), it shares many characteristics with LCCs, including a track record of profitable growth, some of the industry’s highest operating margins, competitive labour costs, a strong management team and good labour relations.

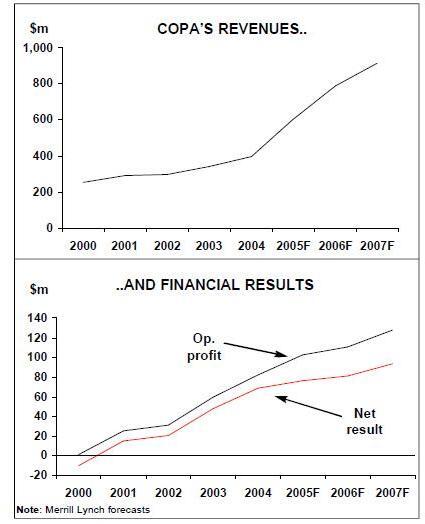

The airline has been profitable for five years, increasing its net earnings from US$14.8m in 2001 to an estimated US$77m in 2005. Operating margins improved from 8.6% in 2001 to 20.6% in 2004 — a level where it remained in 2005, which was among the best in the airline industry.

Like most LCCs, Copa is a growth airline. Between 2000 and third–quarter 2005, its ASMs increased by 74%. The airline plans to double its fleet to 50 aircraft by the end of 2009. And interestingly, like JetBlue, it has just introduced to service the Embraer E190 as its second fleet type.

Copa also benefits from a strategic alliance with Continental — one of the healthiest legacy carriers. The unusually comprehensive pact is regarded as one of the most successful airline alliances in the Americas.

Immediately before the IPO, the deal was extended by ten years until 2015.

However, analysts have mentioned several potential problems related to growth. First, there is the challenge of managing rapid growth while also integrating a new aircraft type to the fleet.

Second, there is the challenge of successfully integrating AeroRepublica, the Colombian carrier that Copa purchased for US$23.4m in April 2005. AeroRepublica potentially offers an excellent growth opportunity, but Copa will have to replace the smaller carrier’s old fleet and turn it around financially, while fending off growing competition. Third, there are concerns that the lack of a good home market and excessive reliance on connecting traffic leaves Copa particularly vulnerable to competition from other network carriers like Taca, Avianca and LAN, as well as future LCCs.

US experience has shown that an airline is skating on very thin ice if it does not have a solid local market that it can dominate — that relying on connecting traffic means not just lower yields but an uncertain future. But is the situation in Panama different?

Copa’s background

Copa’s background and growth path have been unusual. Established in 1947 as a joint venture between Pan Am and local Panamanian investors, the airline led a very quiet existence until new owners and management arrived in the late 1980s. The Motta Group — a major economic force in Panama with interests in banking, insurance and telecommunications — acquired a majority stake in Copa in 1986, which led to a growth phase in the 1990s.

A new management team, led by the current CEO, took over in 1988. The US–educated, bicultural and highly regarded leadership initiated and guided the airline through several important strategies.

First and most significantly, the new management saw an opportunity to develop connecting traffic via Panama’s Tocumen Airport, and Copa began a hub operation there in 1992. The hub has grown to become the airline’s most valuable asset, now offering connections between 800–plus city pairs.

Second, in 1998 Copa’s management secured another unique growth opportunity by forging the alliance with Continental, which also involved the Houston–based carrier acquiring a 49% stake in Copa. Since Panama signed an open skies ASA with the US in 1997, the alliance enjoys antitrust immunity in the US, which has enabled the airlines to conduct joint pricing, scheduling and revenue management, in addition to co–branding, code–sharing and FFP cooperation.

However, the alliance goes much deeper, in that it also includes cooperation on information technology, coordination of maintenance programmes and joint purchasing of insurance, aircraft, spare parts etc. Copa believes that it has been able to achieve economies of scale that would be difficult to achieve for an airline of its size; for example, its insurance costs have probably halved. In addition, Copa has benefited from a transfer of know–how from Continental.

Third, in 1999 the management initiated a vital part of Copa’s transformation into a successful modern airline: complete fleet renewal. The process, which was completed last year, replaced the carrier’s 737–200 fleet with brand new 737–700/800s and E190s.

The December IPO

This very interesting decade of so in Copa’s history culminated with the opportunity to go public in December simply because Continental needed cash. The Houstonbased airline and the Panamanian 51%- owner CIASA (Corporation de Inversiones Aereas), which is controlled by members of the Motta, Heilbron and Arias families, each sold about 9m Class A common shares in the IPO (including over–allotments) at US$20 a share.

The sellers each collected about US$172m in total proceeds, which for Continental represented a nice gain on the US$53m it paid for the 49% stake in 1998. Furthermore, Continental has collected an estimated US$70m in profits from Copa in the past two years, plus US$10m in dividends.

The IPO reduced Continental’s ownership in Copa to 27%, which gives it the right to designate two of the 11 directors. CIASA, which now has a 29% stake, remains in control through its ownership of 100% of the Class B shares, which carry voting rights, and the right to designate six directors (the remaining three directors are independent, pursuant to NYSE rules). CIASA also has the right of first offer for any shares that Continental may propose to sell in the future.

There were suggestions that Continental may have considered this to be a good time to exit Copa, given the future risks associated with growth and competition in the Central American markets. But that is unlikely; Continental simply needed cash to meet its pension obligations — it immediately contributed US$50m of the IPO proceeds to its pension plans. The airline said that it wanted to keep its promises to employees, even in these difficult times.

JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker described Continental’s remaining 27% Copa stake as its "last and final liquidity raising option, should fundamentals deteriorate". Continental’s lock–up period expires in June. While Copa received no proceeds from the IPO, it established a foothold in the US capital markets, which it can tap in the future for growth funds.

The Panama hub advantage

Back in the early 1990s, Copa’s management saw an opportunity to develop connecting traffic from multiple points in the Americas via Panama because of the unique advantages offered by the country and its main airport.

First of all, the Panama hub is geographically well located, allowing 737–700s to fly nonstop to practically anywhere in the Americas. The airport benefits from a sea level location — the two key competing airports in the region are at hot and high locations — and favourable weather, which has given Copa excellent on–time performance and completion factors.

Because of its manageable size and Panama’s policies accommodating transfer passengers, the airport offers easy transfers and short connecting times.

Tocumen has two parallel runways (something that is not common in Latin America), is not gate–constrained and has ample room to grow. The US$70m first phase of an expansion project launched in 2004, due to be completed this April, has added eight new gates with jet bridges, to bring the total gates to 22, along with extra parking positions and improved facilities. The second phase of the expansion could add another five gates.

According to Copa executives, Tocumen Airport is also in the lowest third in terms of costs in Latin America and probably in the world. The geographic reach provided by Panama’s location has allowed Copa to develop a nicely diversified revenue base. In 2004 its revenues were generated as follows:

Panama 16%, rest of Central America 15%, the Caribbean 13%, Colombia 10%, rest of South America 29% and North America 17%.

Copa also benefits from having its home base in an attractive business environment.

Panama’s stable, dollar–based economy has meant low inflation, and GDP growth has been strong in recent years. Copa faces less currency risks than many other Latin American carriers, and the low tax environment has meant only a 10% basic tax rate.

Copa benefits from Panama’s role as a major financial, trade, shipping and international business centre, arising from the existence of the Panama Canal. The country is home to many regional offices of multinational corporations and international institutions. As a result, it generates international business traffic way beyond the size of the population (3m, the majority living in Panama City).

A planned US$6bn–plus Panama Canal expansion project, which will go to a referendum this year, would further benefit Panama’s economy and Copa. And the country is a growing tourist destination, following in Costa Rica’s footsteps. The past couple of years have seen an accelerating construction boom, fuelled by tourism and retirees from the US, Canada and Spain buying second and third homes in Panama.

Through its "Hub of the Americas", Copa currently operates about 80 daily flights to 30 destinations in 20 countries. Another 120 destinations are served via code–shares mainly with Continental and to a lesser extent with Mexicana, Gol and Gulfstream International Airlines. Copa flies to cities as far north as New York and Los Angeles and as far south as Sao Paulo and Buenos Aires. Substantially all of its flights either depart or arrive in Panama. Transit passengers account for an estimated 80% of total traffic.

Copa does not currently provide a domestic service. Travel within Panama is mostly by ground transport, as distances are short, though there are two local airlines — Turismo Aereo and Aeroperlas — operating turboprops of less than 30 seats. Those airlines operate to a domestic terminal in Panama City that is a 30–minute drive from Tocumen.

The business model

Copa is a hub–and–spoke carrier, catering primarily for high–fare business passengers in connecting markets that typically lack nonstop competition, but it also has a reasonably competitive cost structure arising from a labour cost advantage.

Business passengers account for around half of Copa’s traffic, which means higher yields, better ability to pass along fuel costs and less seasonal variation.

Copa has a strong brand and a reputation for quality service, based on an award–winning in–flight service and operational metrics that are among the best in the world. Significantly, the airline appears to have succeeded in creating a Southwest/Gol–style employee culture "based on teamwork and focused on continuous improvement". The highly motivated workforce benefits from the best training practices, performance–based profit sharing etc.

The relationship with Continental has further enhanced the brand. Copa’s "Clase Ejecutiva" is virtually identical to Continental’s executive class, except that it has "a Latin flavour". Aircraft liveries and aircraft interiors are also similar, while Copa benefits from access to Continental’s OnePass FFP and airport lounge programmes.

According to the IPO prospectus, Copa’s fare structure is "designed to balance load factors and yields in a way that maximises profits" and the aim is also to "maximise total revenues while remaining generally competitive". This is very US legacy–style.

Copa participates in all the major GDSs, including Sabre, Amadeus, Galileo and Worldspan. In 2004 about 75% of its sales were through travel agents or other carriers. The airline operates 78 ticket offices, plus 17 co–branded with Continental.

The goal is obviously to boost Internet sales. Copa began accepting ticket purchases through its web site in January 2003, reducing the cost of each booking to 25% of a travel agency booking, but in 2004 still only 0.8% of the airline’s total sales were through the site. Copa is in the middle of the pack in terms of unit costs. Its CASM, at 8.7 cents per ASM in 2004 or 9.1 cents in the first nine months of 2005 (7 cents and 6.5 cents excluding fuel), was similar to WestJet’s — lower than the unit costs of the US legacy carriers but higher than most LCCs'.

The cost structure is excellent for a hub–and- spoke carrier that operates in a relatively healthy revenue environment. Copa attributes it to its young fleet, efficient operations (including high aircraft utilisation resulting from high average stage length) and Panama’s low labour costs.

However, JP Morgan’s Jamie Baker argued in his initiation report that Copa’s cost advantage is almost entirely driven by what he called the greatest labour cost advantage he had ever witnessed at an airline. In Baker’s estimates, Copa’s unit labour costs are nearly 30% below those of JetBlue, the US labour cost leader.

That differential reflects lower wages and salaries in Latin America. According to Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg, a Copa pilot earns about US$35,000 in annual salary, compared to the average pilot salary of well above US$100,000 in the US. However, Heilbron indicated recently that the labour cost advantage over other Latin American carriers arises from better productivity, because "we pay better than most countries in Latin America".

Copa benefits from excellent labour relations and does not foresee labour cost pressures. However, some analysts feel that because 59% of the workforce is unionised and because contracts are currently amendable with the flight attendants and mechanics, with the pilots following in 2008, the situation warrants monitoring.

Copa’s total CASM has been on a declining trend since 2000 and the airline continues to seek cost reductions. There is scope to reduce distribution costs through increased web and direct sales, as well as improving efficiency through technology and automated processes. Challenges include re–fleeting and modernising AeroRepublica to give it the right cost structure. The growth of Copa’s E190 fleet will have some negative impact on CASM, but that will probably be offset by the impact of significant ASM growth.

Copa’s business model works well because the airline operates in a relatively stable competitive environment. The main competitors are Taca and its partner American, and to a lesser extent Colombia’s Avianca and Chile’s LAN. However, competition in the region can be expected to progressively intensify.

First, there are the network carriers in neighbouring countries that are keen to strengthen their own hubs. Copa noted in the IPO prospectus that Taca had recently made aggressive fare–cutting moves, to which it had been forced to respond. However, Avianca may pose a bigger longer–term threat, now that it has emerged from bankruptcy with the help of new owners who want to aggressively grow the airline and the Bogota hub.

Second, there will be the LCCs keen to offer low–fare point–to–point services that bypass the network carriers' hubs. The theory, based on what has happened in the US, is that Copa will be particularly vulnerable to such competition because of its small home market and reliance on connecting traffic.

However, Copa’s leadership believes that the airline’s focus on the thinner intra–Latin America markets, rather than trunk routes, will keep it from much contact with LCCs, which typically prefer high–demand routes. In other words, not many of Copa’s markets are large enough for hub bypass service.

On about 600 of the 800 city–pairs, Copa transports fewer than 10 passengers a day. The airline consolidates traffic from numerous points via the hub to achieve a satisfactory load factor to every destination city.

The Sao Paulo–Managua (Nicaragua) market provides an example of how Panama’s location and market size come together to make the business model work. The passenger has three choices: flying via Miami (elapsed time 12 hours 45 minutes), via Lima and San Jose (over 15 hours) or via Panama (less than 10 hours; straight line, no immigration or customs). Of the four daily passengers in that market, three choose Copa. A similar thing happens in 600–plus markets daily.

Consequently, Copa considers its business model "defensible", one that is hard to duplicate. Nevertheless, the airline must brace itself for having some traffic siphoned off by LCCs in its largest and most lucrative markets in the future.

Growth plans

After retiring its last two 737–200s in 2005, Copa’s 24–strong fleet at year–end included 18 737–700s, four 737–800s and two E190s. There were firm orders for seven 737NGs (700/800s) and 10 E190s, plus options for 18 E190s and purchase rights for ten 737NGs.

The current plan is to double the fleet to 50 aircraft — 30 737NGs and 20 E190s — by the end of 2009. This would mean 19% average annual capacity growth, which would be not dissimilar to the growth seen in recent years. There would still be 19 options at the end of 2009, adding flexibility to the fleet plan.

Those figures exclude AeroRepublica, which operated 11 MD–80s and two DC–9s at year–end. The fleet had an average age of 22.4 years at the end of September. Copa’s executives said in late February that they were in the final stages of analysing the re–fleeting of the Colombian carrier. The company indicated earlier that additional aircraft orders for AeroRepublica were likely.

Copa chose the E190, which it will operate with 94 seats, essentially for the same reasons as JetBlue — because its small size and highly efficient operating characteristics made it the ideal aircraft to open new mid–sized markets that could not be served profitably with 150- seaters and to add frequencies on existing routes.

The overall growth strategy is simple: to continue to strengthen the Panama hub with increased frequencies and new destinations. Copa believes that it has significant growth potential because a large number of cities in Latin America do not have connectivity within the region — they may have domestic service and nonstop flights to the US but not adequate intra–regional links. In late February Copa announced the addition of three such cities — Manaus (Brazil), Santiago de los Caballeros (Dominican Republic) and Port of Spain (Trinidad) from June/July, to be served with E190s.

The airline expects to de–peak the hub, to add two new flight banks to the present two (morning and evening), as it grows over the next few years. That will help improve asset utilisation.

Copa executives consider AeroRepublica as a "very interesting growth opportunity", providing access to Latin America’s third largest country that has a population of 45m and a relatively undeveloped aviation market. Panama was part of Colombia until 1903 and the two countries have strong links. Copa already serves six cities in Colombia. AeroRepublica is Colombia’s second–largest carrier, with a domestic network of 11 cities and a market share of 30%.

In the first place, AeroRepublica will provide feed to Panama — a process that began in December with services from Cartagena and Medellin. The airline has also added frequencies within Colombia and will introduce Cali as a new domestic destination later this year.

AeroRepublica represents a demanding project for Copa, requiring capital spending and management time. While recognising the acquisition’s longer–term strategic value, some analysts believe that the carrier will represent a drag on Copa’s profit margins for several years. However, Copa can afford it. The company is set to continue to post strong earnings, though operating margins are expected to decline to the 14–15% level this year and in 2007. The balance sheet is healthy, with cash of US$129m (24% of annualised revenues), total assets of US$846m and total debt of US$430m at the end of September 2005. The lease–adjusted debt/capitalisation ratio was 73% — lower than JetBlue’s and AirTran’s. Contractual obligations on aircraft purchases, operating leases and debt amount to a manageable US$200–300m annually over the next three years.

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

| 737-200 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 737-700 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| 737-800* | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| E190 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 15 | 20 |

| Total | 22 | 24 | 30 | 37 | 43 | 50 |