Lufthansa: return on core business refocussing

March 2005

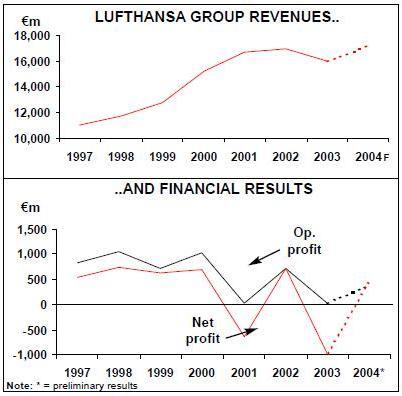

After delivering a €1bn net loss in 2003, the Lufthansa Group recovered well last year by focussing on its core businesses, selling off nonstrategic business units and driving through cost cutting. Has Germany’s flag carrier done enough in the face of a high structural cost base and a continuing challenge from the low cost carriers?

Lufthansa operates to more than 330 destinations in 90 countries, making it the third–largest European passenger airline — after British Airways and Air France — as well as the world’s second largest cargo airline, behind only Fedex.

Although passenger traffic rose by 1.6% in 2003, the Group was hit by not only SARS and the Gulf war, but also by losses at associated tour operator Thomas Cook (which the Group owns 50% of) and at catering subsidiary LSG. So while the Group made an operating profit of €36m on revenues of €16bn in 2003, the net loss for the year was a staggering €984m, of which €700m came from write–downs at LSG.

This prompted Wolfgang Mayrhuber, the new CEO and Chairman of Lufthansa Group (he took over from Jurgen Weber in June 2003), to instigate a twin strategy of cost cutting across the Group, allied with a refocussing on the core businesses of airline and cargo, supported only by subsidiary operations that added real value to these core business units.

Cost cutting targets

The Group targeted cost cutting of €1.2bn by the end of 2006, split evenly between staff, external suppliers, internal suppliers and "production framework/processes" (i.e. aircraft utilisation, regional airlines and Lufthansa’s hub operations).

Of the overall total, €430m of cuts was to be made by the end of 2004, and in October the Group said it was just about on target to meet that goal, with management concerned only by a delay in cutting labour costs.

Those concerns stemmed from marathon negotiations with pilots, which started back at the end of 2003. In October 2004 Wolfgang Mayrhuber threatened that future growth would be concentrated at low cost subsidiaries (such as Germanwings) or even fellow Star alliance members if agreement with unions couldn’t be reached quickly.

Not surprisingly, this wasn’t well received by unions, who described Mayrhuber’s statement as "completely incomprehensible".

Nevertheless, in December 2004 Lufthansa finally agreed a pay round with the pilots, which management estimates will reduce its cost base by €55m in 2005. The deal with the pilots' union Vereinigung Cockpit covers 4,400 pilots at the main airline, the cargo operation and at Germanwings, and includes a pay freeze until the end of March 2006, alterations to the pension scheme and the addition of an extra two hours to pilots' flight schedules every month.

In return, the union has an assurance that there will be no job losses over the period.

A separate deal with Verdi, the ground staff union that represents 37,000 Lufthansa personnel, was agreed in the same month. The agreement lasts until the end of 2006 and includes flexible working and overtime measures for existing ground staff as well as a reduction in holiday entitlement and other conditions for new staff.

In return, although pay scales will nominally remain frozen, ground staff will receive a bonus of 0.5% of their salary in 2005 and 1.6% in 2006, profit sharing has been introduced and — as with the pilots — Lufthansa has given guarantees that there will be no job losses over the period. Overall, Lufthansa expects the deal to cut ground staff costs by €150m over the next two years.

Lufthansa has also cut costs at its call centre in Kassel, western Germany, by 29% after an agreement with the 380 staff there that includes a longer working week, a reduction in overtime hours and a 75% cut in pay for working on Sundays and holidays.

This leaves 13,700 cabin staff, represented by the UFO union, as the last major group yet to agree a pay deal, although management is confident a deal will be agreed before the end of the first quarter of 2005, with terms similar to those agreed with ground staff.

Elsewhere, distribution is another area where Lufthansa has been making real progress in cut–ting costs, although — inevitably — travel agents have tried to resist the measures imposed by the airline.

In September 2004 Lufthansa stopped paying commission to German travel agents on all flight tickets (payments averaged 5%-9% per ticket face value), forcing agents to charge their customers separately for their time and advice. Around 660 travel agents staged a three–day boycott of Lufthansa flights in protest, but they had little choice but to accept the move.

However, the simmering ill–will of German travel agents towards Lufthansa became worse when in January this year the airline reduced its online booking fee from €30 to €10 for tickets to European destinations, and from €45 to €15 for intercontinental destinations.

The cuts in the fees are in addition to the €10 discount that Lufthansa gives on all tickets booked via the internet, which effectively means that European tickets can be booked via Lufthansa’s web site for no additional cost at all — as opposed to the service charges that travel agents levy when customers book tickets through them.

German agents immediately lodged a complaint with the German cartel office, but it’s unlikely the office will overturn Lufthansa’s policy, particularly given the precedent set in Austria, the next most important market for Lufthansa.

There, Lufthansa ceased paying 5% commission from November 2004 but, after Austrian travel agents filed a lawsuit against Lufthansa, in January an Austrian court ruled that the airline was doing nothing illegal.

Also in January, Lufthansa ended its ongoing dispute with Dusseldorf airport over an increase in landing fees. The airport had imposed a 7.1% increase, but after a boycott of the fee by a dozen airlines — of which Lufthansa was by far the most important — the airport backed down and introduced a 3.5% rise instead.

Profit recovery

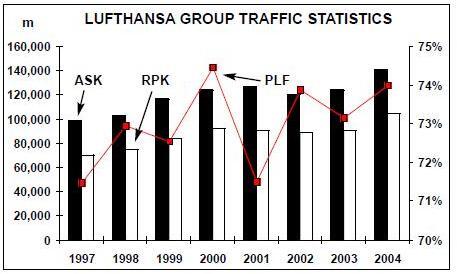

The cost cutting through last year helped Lufthansa Group record an operating profit of €251m in the nine months to September 2004, compared with an operating loss of €154m in 1Q- 3Q 2003. Turnover rose 7.7% to €12.7bn in the period. The Group’s passenger business saw RPKs increase by 16.2% in the three–quarters, year–on–year, ahead of a 14.3% rise in ASKs and resulting in a 0.8 percentage point increase in passenger load factor to 74.3%.

Of the 1Q–3Q Group operating profit, the airline division was responsible for €237m, representing 94% of the total. But other than engineering specialist Lufthansa Technik, all of the Group’s other subsidiaries either made losses or small profits at best. Most worryingly, in 1Q–3Q 2004 LSG Sky Chefs — the catering division — and Thomas Cook (which Lufthansa owns jointly with German retailer KarstadtQuelle) made €114m and €142m operating losses respectively.

These are worrying figures, although the underlying performance of the subsidiaries has to be taken into account. While a restructured Thomas Cook is expected to break even for the full year, the prospects for LSG are not so good. Radical restructuring at the catering subsidiary over the last 12 months — including more than 8,000 job losses and the sale of Chef Solutions, which made bakery products for the North American market — appears not to have made much of an impact.

In November 2004, Hanns Rech — the CEO of LSG — resigned with immediate effect, reportedly after the Lufthansa Group cancelled plans to float off the subsidiary yet again (an earlier attempt to launch an IPO had to be abandoned after September 11). It appears that LSG will continue to drag down Group results for the foreseeable future.

Nevertheless, the Group is pushing on elsewhere with its strategy of disposing what it considers to be non–core assets. In November 2004 Lufthansa Group added another substantial sum to its coffers from selling its 31% stake in Tank & Rast, a German motorway services firm, which was acquired by Terra Firma, a UK private equity company, for €1.1bn.

Further sell–offs could include Lufthansa’s 30% stake in bmi, which it bought in 1999 and 2002.

A UK newspaper claimed in January that Lufthansa was looking to sell its stake, partly in order to release the airline from a binding put option that obliges Lufthansa to buy the 50% plus one share that belongs to Michael Bishop, bmi’s founder.

Bishop can exercise this option anytime from the end of 2005 until 2009, at a fixed cost to Lufthansa of €325m — a sum that analysts estimate is significantly higher than the true market worth of the airline.

Lufthansa is reported to be negotiating with both Virgin Atlantic and British Airways, although the German airline will not comment, and sources suggest both potential acquirers would require a very low price in order to relieve Lufthansa of its investment. However, this may be part of the negotiating game, as bmi controls 85 slot pairs a day at London Heathrow, giving it a valuable 14% share of all slots at the airport.

Even without a forced purchase of further shares, Lufthansa’s involvement with bmi has been nothing short of disastrous.

The original intention of the deal was to secure feed from bmi’s operation at London Heathrow into the Lufthansa network across Europe. However, since Lufthansa bought its stake, bmi has racked up three successive years of operating losses, forcing the German airline to write off the book value of the investment and take its share of the losses, which were €66m in 2002 and €76m in 2003.

Although Lufthansa Group’s avowed strategy is to divest rather than increase its portfolio, it may be tempted to make investments in specific circumstances.

For example, although Lufthansa’s stake in CRS Amadeus is now down to 5.1%, in January a Spanish financial newspaper claimed Lufthansa wants to raise its stake back up to11% by acquiring parts of the equity held by Air France and Iberia. At first sight this would appear to be an odd move given that Lufthansa raised €394m (giving it a book profit of €292m) when placing a 13.2% stake with institutional investors on the Madrid stock market in February 2004.

But at the time Lufthansa said it would hold on to its remaining stake, and its strategy may be influenced by the fact that two UK equity funds — Cinven and BC Partners — are trying to acquire the CRS in a complicated deal that involves the de–listing of Amadeus and the setting up of a new holding company.

While Air France and Iberia would reduce their stake, the deal may be structured so that the three airlines end up with more equal shares than at present, hence leading to speculation that Lufthansa’s stake will increase.

Another possible investment may be in Deutsche Flugsicherung, the German air traffic control service, which the government plans to privatise in 2005. However, this would be a reluctant investment by the Lufthansa Group, going against its disposal policy and essentially forced on it by a fear that the service might become a privately held monopoly.

Less feasible should be an investment in a fellow European flag carrier, which would be expensive, divert management and help consolidate the industry to the benefit of rivals.

Analysts were concerned when Lufthansa attempted to acquire Swiss International Air Lines in 2003, before the Swiss airline decided it wanted to join the oneworld alliance. Lufthansa was particularly interested in acquiring Swiss’s long–haul routes, a prospect that at the time was not well received by Swiss’s management and shareholders, who wanted to retain the independence of the airline. After Swiss’s flirtation with oneworld came to nothing following a disagreement with British Airways on FFP linkage, in January 2005 Lufthansa insisted it was no longer interested in acquiring the airline. However, reports to the contrary persistently come out of Switzerland, and the Swiss finance minister stated earlier this year that a partnership between Swiss and Lufthansa is an option the government is considering.

Unconfirmed Swiss sources say a informal deal has been already been agreed whereby as long as Swiss can fulfil certain conditions — including a recapitalisation of at least €200m from existing shareholders, new agreements with pilots and ground staff, and the cancellation of existing aircraft lease contracts — then a partnership will be announced by the two airlines this autumn, potentially leading to a full merger in the summer of 2006.

And in September 2004 Pietro Lunardi, the Italian transport minister, said that Alitalia would do better by aligning itself with Lufthansa than by pursuing closer links with SkyTeam partner Air France.

Lufthansa Technik acquired 40% of Alitalia’s maintenance subsidiary in 2003, but the suggestion of a link with the German airline was refuted by Giancarlo Cimoli, Alitalia’s CEO, and given Alitalia’s continuing financial woes it’s unlikely that Lufthansa is interested, particularly as Lufthansa owns Air Dolomiti and code–shares with Romebased Air One already. In any case, in October 2004 Lufthansa joined seven other airlines in complaining to the European Commission about the Italian government’s planned rescue of the flag carrier.

Upmarket push

With the brakes applied to significant new portfolio acquisitions, Lufthansa Group is instead investing in its airline product and aircraft. On the former, Lufthansa traditionally has the highest proportion of first and business class customers among the European majors — historically around the 20% level. However, this dropped to 16% during the first nine months of 2004, and the airline is making a determined effort to recapture its former position.

Lufthansa invested €15m in Frankfurt’s new first and business class terminal, which opened in December 2004, and is launching a similar terminal at Munich, scheduled to open in 2006.

However, Lufthansa says that no more than 350 passengers will use the Frankfurt facility each day, and analysts are divided as to whether Lufthansa’s push for business and first class is a good move, given that these markets may be in a steady and permanent long–term decline.

But Lufthansa is pushing on regardless. The Group already offers an executive jet service between Munich and Dusseldorf to Chicago and Newark using aircraft from Swiss charter airline PrivatAir, but this year a European corporate jet service is being launched, enabling first and business class customers to connect to/from Lufthansa’s hubs from across Europe.

German sources suggest Lufthansa is in talks to launch this service with NetJets, the US corporate jet business that offers fractional ownership to corporations and small companies.

Other product moves include the introduction of broadband internet connection on long–haul services and the launch of an exclusive FFP within the Miles and More scheme, to be called "Hon Circle". It will be open to passengers that fly more than 600,000 miles in a two–year period, giving them privileges such as access to the new first/business terminals at Frankfurt and Munich.

Fleet development

| Fleet | Order | Options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lufthansa | |||

| A300-600 | 15 | ||

| A319 | 14 | ||

| A320 | 33 | ||

| A321 | 26 | 6 | |

| A330 | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| A340 | 40 | 7 | |

| A380 | 0 | 15 | |

| 737 | 59 | ||

| 747 | 30 | ||

| Total | 225 | 26 | 14 |

| CityLine | |||

| CRJ100/200 | 43 | ||

| CRJ700 | 20 | ||

| RJ85ER | 18 | ||

| Total | 81 | 0 | 0 |

| Lufthansa Cargo | |||

| MD-11F | 16 | ||

| 747-200 | 3 | ||

| Total | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Air Dolomiti | |||

| CRJ200 | 5 | ||

| ATR500/700 | 16 | ||

| Total | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Group total | 346 | 26 | 14 |

The Lufthansa Group currently has a fleet of 346 aircraft (see table). On short–haul, the main airline has 59 737s and 73 A320 family aircraft, but some of the 737s–300s and -500s are more than 16 years' old, and now that a pay deal has been done with the majority of airline staff, a short–haul order is likely to be placed sometime this year.

Lufthansa is keen to boost it short–haul network, the improvement of which took a lower priority last year as a result of both pay negotiations and a focus on long–haul expansion (see below).

However, this does not necessarily mean a large increase in capacity, as the Group’s short–haul plans are linked to the general effort in cost–cutting.

From the summer of 2004 Lufthansa improved short–haul fleet productivity by 10% through cutting turnaround time by five minutes and reducing aircraft scheduling complexity. Peaks at the Munich and Frankfurt hubs were flattened slightly by spreading some peak departures to other parts of the day,

In March 2003 Lufthansa carried out a strategic review of its regional operations, largely as a response to the encroachment of the LCCs (see Aviation Strategy, December 2004 and January/February 2005).

The result of the review was the launch of Lufthansa Regional in October 2003 to manage the operations of Lufthansa CityLine, Eurowings (49% owned by Lufthansa), Air Dolomiti (in which Lufthansa increased a 21% stake bought in 1999 to 100% by November 2003) and turboprop partners Augsburg Airways and Contact Air. All these airlines, other than Air Dolomiti, use Lufthansa Regional livery, and they coordinate operations and routes within and to/from Germany. Lufthansa Regional replaced the former Team Lufthansa partnership, which included the same airlines (as well as Cirrus Airlines and Cimber Air, which decided not to join the new structure) in a looser regional alliance arrangement.

The Lufthansa Regional airlines concentrate on providing feeder flights into the Frankfurt and Munich hubs, although increasingly they also offer regional, point–to–point routes.However, the rise of the LCCs in Germany — both domestic and foreign — is a severe threat to Lufthansa’s regional operations, and the airline is "struggling to keep regional routes alive" according to Werner Korr, senior vice president of Lufthansa Regional. The regional subsidiary, which has a combined fleet of around 160 aircraft, is looking to make a substantial order for aircraft in the near future. New aircraft are critical given the cancellation (after the collapse of the manufacturer) of an order placed by Lufthansa CityLine back in 2002 for 100–plus Fairchild Dornier 728s, which had been scheduled for delivery from 2003 onwards.

Bombardier and Embraer types are now being examined, after the A318 was excluded as a possibility early in 2004.

But the order is complicated by the fact that CityLine, which operates a fleet of 63 jets and 18 turboprops to 60 destinations throughout Europe, has an agreement with pilots' union Vereinigung Cockpit that prevents the airline from operating more than 18 aircraft with capacity of greater than 70 seats. However, Lufthansa wants to increase the capacity of its regional feeder routes through a greater average set size per aircraft, so the two sides have to agree a new deal for CityLine equipment.

Unions and management are to start negotiations shortly, and if agreement is reached, expansion at other parts of Lufthansa regional is likely to be offset by a smaller fleet at CityLine (by up to 14 aircraft), which will start using larger capacity Embraer 170s and 190s.

The pilots' union is wary because Lufthansa also has a target of reducing costs at regional operations by €100m in 2004–05. CityLine pilots and cabin crew agreed a pay deal in early 2004, including a pay freeze for 30 months, which — along with greater staff flexibility and other productivity improvements — is cutting around €40m from the CityLine cost base. The union is worried that a switch to aircraft with larger capacity may be used as an opportunity by the Group to make further cost cuts at the expense of its members.

At Eurowings, where Lufthansa increased its stake from 24.9% in 2001 to 49% in April 2004, the Group plans to dispose of 15 ATR–72s and concentrate on RJ operations, some of which will transfer over from Air Dolomiti. The RJs will be partly replaced at the Verona–based airline by five 100–seat BAe 146–300s, which are expected to be ordered shortly.

Once the fleet readjustments are made, it’s unlikely that Lufthansa Regional and the mainline operation in Europe will ramp up capacity, at least in the short–term. In 2004 overall capacity rose by 13.4%, but RPKs grew by 14.7%, resulting in a 0.9 percentage point rise in load factor to 74%.

However, within this, short–haul capacity rose by only 4.5%, and traffic by 5.6%. In 2005 Lufthansa plans to increase overall capacity by just 5%-6%, and it appears as if short–haul capacity will be level at best.

If there is any increase in capacity, it’s likely to be to eastern Europe. In the summer of 2004 routes were launched to Gdansk, Poznan, Krakow, Bratislava, Tirana and Tallinn, while Lufthansa saw an 11% increase in passengers carried between Germany and Russia/CIS in the first three–quarters of 2004. Russian observers believe that Lufthansa is examining a switch of airports in Moscow in the winter of 2005/06, from Sheremetyevo to Domodedovo, a claim that Lufthansa has not denied. Lufthansa operates more than 50 flights a week from Munich, Frankfurt and Dusseldorf, but Domodedovo is upgrading its facilities and wants to attract foreign airlines. Also in eastern Europe, Lufthansa is sponsoring Adria Airways and Croatia Airlines as members of the Star alliance’s new "regional membership" scheme.

Meanwhile, code–sharing is being extended within Europe. In December 2004 Lufthansa extended its longstanding code–sharing agreement with fellow Star member Singapore Airlines (which started in 1998) to flights between Spain and Germany, while in February 2005 Lufthansa began code–sharing with TAP Air Portugal on all the airlines' flights between Germany and Portugal.

Lufthansa and TAP — which is joining the Staralliance this year — aim to extend code–sharing to long–haul routes into the Asia–Pacific region later this year.

Long-haul plans

The main Lufthansa airline has a total of 93 long–haul–aircraft, but despite increasing long–haul capacity by 18% in the summer of 2004 through extra services on a number of routes, some are still operating on close to 100% load factors.

New aircraft are a priority. Lufthansa has 15 A380s on order, which will start arriving at the end of 2007 and be used on routes out of the Frankfurt and Munich hubs to North America and the Asia- Pacific region using a three–class 550–seat layout. At the launch event for the A380 in January, Wolfgang Mayrhuber said the airline would order further A380s, though he gave no indication of the timing. In December 2004 Lufthansa ordered seven A340–600s, for delivery in 2006 and 2007.

These will join 40 A340s in the fleet, with Lufthansa also holding options for eight A340–300s.

Much of the new capacity will be put onto Asia- Pacific routes. Lufthansa currently operates to 19 destinations in 10 Asian countries, with more than 150 flights per week, and after passengers carried on Asia–Pacific routes rose by 25% in 2004, Lufthansa is aiming for double–digit traffic growth again this year.

A key area for expansion is China, with a target of a 50% increase in revenue on services to/from the country over the next two years following a revamped China–Germany air services agreement signed in September 2004, as well as a relaxation of visa requirements. Lufthansa operates more than 40 flights a week to Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong, making it the leading European airline to China. Lufthansa also code–shares with Air China on international routes and with Shanghai Airlines on domestic routes to 15 code–share destinations, and under the terms of the revised ASA it can double the amount of code–share destinations.

However, the Air China code–share deal will be under threat if the Beijing–based airline goes ahead with a plan to sell a 9.9% stake to Cathay Pacific at the same time as it IPOes on the Hong Kong stock exchange later this year. An MoU for this deal was announced in October 2004, but it caught analysts unaware as the Chinese airline previously had close ties to Lufthansa and was expected to join Star in due course. Only two months' before, Lufthansa and Air China had agreed to extend their joint venture agreement for the Aircraft Maintenance and Engineering (Ameco).

The profitable Beijing–based Chinese maintenance company was launched in 1989 and is 40%- owned by Lufthansa. The two airlines agreed to extend the company until 2029, along with an injection of $100m in capex between them over the next four years.

Following that deal, it is believed that Air China asked Lufthansa Group to invest in the Chinese carrier — a request that Lufthansa turned down, thus leading Air China to approach a rival airline. And while in public the Star alliance insists that it still wants Air China to join, it’s inevitable that the Chinese airline will link with oneworld, thereby forcing Lufthansa to find another code–share partner into China.

With China Southern expected to join SkyTeam, the only realistic candidate left for Lufthansa is Shanghaibased China Eastern. It had had previously been looking to join oneworld, but will now look elsewhere for a global alliance following the proposed Air China–Cathay deal, which Li Fenghua — chairman of China Eastern — described with typical Chinese understatement as "a little bit unexpected".

India is another long–haul market that interests Lufthansa, as it’s the second–fastest growing market for the airline. Lufthansa started an extensive code–sharing partnership with Air India for the 2004/04 winter timetable, with code–sharing on both airlines' routes between Germany and India to be followed later this year by FFP linkage, sales and marketing co–operation and co–ordination on planning new routes. At present Lufthansa operates routes to Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Bangalore from Frankfurt or Munich, but plans to double capacity over the next two years.

A three–times–a week Frankfurt–Hyderabad service started in February, and extra frequencies are being added on Munich–Delhi and Frankfurt–Bangalore. Lufthansa’s weekly flights between Germany and India now total 35, bringing Lufthansa’s share of the European–Indian market to more than 15%.

The code–sharing partnership may also be a pointer to eventual Air India membership of the Star alliance, which currently doesn’t have a member in the Indian sub–continent. And India is a potential destination for Lufthansa’s A380s when they arrive in 2007, although there would have to be substantial improvements to the airport infrastructure.

Also as part of the continued long–haul push, in October 2004 Lufthansa launched a Munich–Kuala Lumpur route and added seven flights each week on its Munich–Bangkok service and three flights on the Munich–Ho Chi Minh City route. Frequencies are also being raised this year to Nagoya in Japan, and Singapore, while Lufthansa is launching a route between Frankfurt and Port Harcourt, an oil port in south Nigeria, from April. And in January this year Lufthansa extended an existing code–sharing deal with United and United Express to 154 extra domestic North America routes.

Cargo boom

Lufthansa Cargo became a separate operation in 1996 and today operates a fleet of 16 MD–11Fs and three 747–200Fs. After losing market share in the early 2000s (its share of the German cargo market dropped from 30% to 25% in three years) through a policy of boosting profitability at the cost of expansion, Lufthansa Cargo has now done a strategic about–turn. It plans to expand capacity through the year and is acquiring four more MD- 11Fs, converted from Lufthansa’s passenger fleet, as well as contemplating becoming a customer for Boeing’s planned 777–200LR. The freighter variant of the A380 is also under consideration, as well as further MD–11Fs and 747–400Fs. However, fleet expansion comes as the cargo airline cuts another 300 staff through this year, on top of the 180 it shed in 2004, as part of the Group cost cutting push.

This represents 10% of the mid–2004 workforce of 4,800. Although revenue rose by 11% in January- September 2004, Lufthansa Cargo made an operating profit of just €4m in the period, due to a combination of the weak dollar, rising fuel prices and tough price competition from other cargo airlines Lufthansa Cargo traffic has almost doubled since 2001, and is likely to rise again within the first quarter of 2005 after weekly cargo flights between Germany and China rose from 14 to 28 a week in just four months. A cargo service between Frankfurt and Guangzhou was launched in October 2004, and the following month Lufthansa Cargo agreed to set up a joint venture with Shenzhen Airlines and Germany’s DEG Bank.

Based in Shenzhen, Jade Cargo International will start operations this year using leased A300–600Fs on routes to the US and Europe. Lufthansa Cargo has a 25% stake in the airline, the maximum allowable for this type of JV in China. Last year a joint venture was also established with the Shenzhen Airport Company to operate an air freight terminal at the airport. Both these deals take advantage of the Chinese government’s relaxation of rules governing joint ventures with foreign companies.

40% of Lufthansa Cargo’s revenues are generated in the Asia–Pacific region, and half of that comes from China. In the first nine months of 2004 a boom in cargo business led to a 4% increase in cargo yield. Martin Schlingensiepen, Lufthansa Cargo’s VP for Asia sales, says: "In just over six months the air cargo industry has gone from excess freighter capacity parked in the desert to full utilisation of capacity worldwide." In particular there was been a surge of goods manufactured in China and destined for European and North American retail outlets in the run to Christmas.

Trouble ahead?

At the end of last year Lufthansa said it was on target to report an operating profit of €300m for 2004, despite the ailing German economy and the increase in fuel prices. In the nine months to September 2004 fuel costs rose by 30% (to €1.3bn) compared with 1Q–3Q 2003, and that was after hedging that saved the company approximately €160m in the period. After resisting the move for several months, in August 2004 Lufthansa introduced fuel surcharges on both short- and long–haul routes. In October these surcharges were increased further, with charges on short–haul flights increasing from €2 to €7, and on long–haul from €7 to €17.

Though the Lufthansa Group appears to have overcome the financial blip of 2003 and is weathering the recession in the Germany economy well, as Wolfgang Mayrhuber says: "The current improved figures cannot hide the fact that we need significantly better operating results in future in order to ensure our company’s viability".

The cost cutting exercise appears successful,with only cabin staff yet to sign a new pay round. On the other hand, the jettisoning of non–core assets has been less successful, primarily because LSG is still on the books and continues to rack up a horrendous loss.

Presuming the LSG losses will be resolved one way or another, the one problem that will continue to dog Lufthansa is the intense competition from low–cost airlines — particularly as the Group still gives the impression that it is underestimating the impact of the LCCs (see Aviation Strategy, July/August 2003) and is seeking to avoid confrontation where possible, instead allowing Germanwings (the LCC owned by Eurowings, 49% of which is owned in turned by Lufthansa) to engage in the messy business of competing on price.

Other than by cutting costs, Lufthansa’s only other discernible tactic towards combating the LCCs appears to be the trimming of capacity. Whereas in the summer of 2005 Lufthansa will increase overall capacity by 1.5%, long–haul seats will rise by 2.4% while short–haul seats will fall by 0.9%. This comes on top of a 2% cut in short–haul capacity in the winter 04/05.

But this begs two questions, the first of which is whether the Group has the discipline to keep doing trimming short–haul capacity over the next few years. More than 50% of Lufthansa’s airline revenue comes from short–haul, a higher proportion than at either British Airways or Air France, and at some point revenue erosion may start to worry executives, even if the reward of doing that is better margins on the remaining short–haul routes.

And as Lufthansa is planning to increase the size of its workforce through 2005 via 500 extra cabin staff and 240 pilots, if there is any slowdown in long–haul growth then the Group may be tempted to switch resources back into short–haul — particularly if larger aircraft are ordered for Lufthansa Regional.

The second question is: even if Lufthansa sticks to a strategy of cost–cutting and trimming back on loss–making European routes, will this make any difference to the advance of the LCCs? Both Ryanair and easyJet have unit costs that a German–based airline with the legacy of Lufthansa will surely find impossible to copy.

Lufthansa’s current cost drive follows immediately behind an earlier one — "D–Check", which was carried out over 2001–2004 and lowered costs and/or raised revenue by €1.6bn. But given its geography and historical legacy, it’s becoming harder and harder for Lufthansa to cut costs (as evidenced by the recent struggle to get new agreements with unions).

There are simply some costs that Lufthansa can never lower to the level of the LCCs. For example, airport and air traffic infrastructure costs are the second–largest cost item for Lufthansa, but according to an internal analysis by Lufthansa, moving its operations from Frankfurt and Munich to London Heathrow would reduce costs by some 30%. Of course the LCCs, largely based at secondary UK and Irish airports, also have a cost advantage over Heathrow. And when Lufthansa’s cost–cutting starts to level–off, yields will continue on their relentless drive downwards. In July–September 2004 — traditionally Lufthansa’s strongest quarter of the year — the average yield on the Group’s European passenger traffic fell by 4.8% compared with 3Q 2003.

Financially, the Group is strong, although in January Lufthansa revealed that as at the end of 2003 it had set aside €491m in reserves to cover the liability on "Miles and More", its FFP that has more than 10m members. However, it is not expected that all of this reserve will have to be used, since approximately 20% of its FFP miles lapse without being redeemed. And in June 2004 Lufthansa raised more than €750m by a rights issue, which will be used largely in paying for the airline’s A380 order — although the move was unexpected, and Lufthansa’s share price fell sharply on the announcement. Indeed Lufthansa’s share price has fallen from €27 in early 2001 to €6.91 in early 2003, although it has since recovered to above the €11 level.

Bullish analysts

On the other hand, analysts are bullish on Lufthansa. As at the end of February, of 21 analysts covering Lufthansa Group, all but four recommended buying or going overweight on the stock.

HypoVereinsbank set a medium–term target of €13.50 for Lufthansa shares, WestLB set a price of €13 and CSFB topped the lot by forecasting a target of €14, up from its previous target of €8.

In fact CSFB rated Lufthansa as its key European flag carrier tip for 2005. Only time will tell whether this bullishness is deserved, or whether analysts have underestimated the long–term impact of the LCCs on Lufthansa.