Republic Airways: rising star of the US regionals

March 2005

Republic Airways Holdings, the parent of Chautauqua Airlines and yet–to–be–certified "Republic Airline", has been described as a rising star in the US regional airline sector.

With its all–RJ fleet, growing 70–seat operations, super–low cost structure and diversified customer base, the Indianapolisbased company is well positioned to benefit from the restructuring that is likely to take place in the regional sector in the next few years. After going public last year, Republic raised additional funds in a secondary offering in February — something that would allow it to be opportunistic. It is rumoured to be seeking to buy US Airways' owned EMB- 170s. It is also talked about as a potential acquirer or investor in Independence Air, which is facing increasing pressure from shareholders to revert back to the fixed–fee regional model.

On the negative side, Republic faces significant partner risk and uncertainty. Of its four major airline code–share partners (US Airways, United, Delta and American), two are in Chapter 11 bankruptcy and one (Delta) still looks very fragile after averting Chapter 11 in late 2004. It is worth bearing in mind that the recent legacy carrier rescue deals may have only moved their troubles by one year.

There is also growing asset risk associated with 50–seat RJs, for which the market is weak. At year–end, all but 11 of Republic’s 111–strong fleet were 50–seat RJs. Unlike some other US regional airlines, Republic actually owns 51 or about half of its 50–seat RJs, and many of the others are on long term leases.

As illustrated by recent events, there is also the risk of being out–manoeuvered by other regional carriers. In mid–February Air Wisconsin secured the right to place up to 70 CRJ–200s in US Airways Express by providing $125m of DIP financing to US Airways, to be converted into equity when the airline emerges from Chapter 11.

This could potentially mean Republic and Mesa losing some of their US Airways business.

However, Air Wisconsin is unlikely to exercise those rights because the CRJ–200s are currently in United Express — evidently, the US Airways Express deal represents merely a contingency plan. Even so, the prospect of some the legacy carriers allocating RJ flying on the basis of regional carriers' willingness to provide debt or equity funding, rather than the traditional criteria of low costs or high service quality, is intriguing.

How will Republic deal with such challenges? What are the key components of its business strategy and chances of long–term success?

Six-year transformation

Republic has been extremely fortunate in attracting both a right–calibre owner and a uniquely talented management. In the late 1990s Chautauqua was still a small turboprop operator, albeit with a 23–year history of reliable operations as a feeder for US Airways. In May 1998 Wexford Capital, a private investment firm, purchased it for $20.1m in cash. Wexford brought in a new management team, established a holding company structure and began to aggressively grow the airline.

The top three executives of the new management team, led by Bryan Bedford as CEO, joined the company in July 1999 from another regional airline, Mesaba. They had an impressive track record there but were frustrated by the lack of growth opportunities.

At Republic, they have implemented a rapid transformation that has seen major RJ growth with US Airways, addition of new code–share partners, introduction of a "single- fleet" regional model, establishment of a platform for 70–seat and larger RJs and a significant lowering of operating costs.

After the 1999 launch of RJ service for US Airways (initially supplementing turboprop operations), new partners were added at a dizzying pace: TWA in 2000, American in 2001 (after its acquisition of TWA) and America West also in 2001. Delta followed in 2002, and in 2003 Delta replaced America West after the latter closed its Columbus (Ohio) hub. United was added in early 2004 — significantly, for Republic’s first 70–seat EMB–170s — and in December the Delta agreement was expanded to include 16 EMB–170s between mid–2005 and mid- 2006.

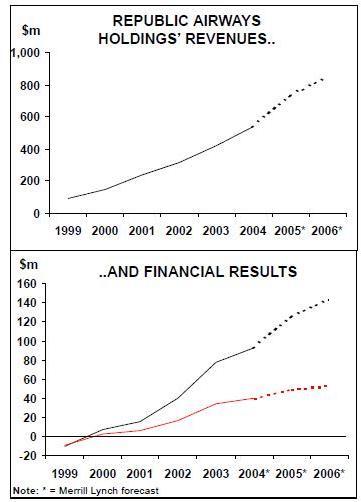

All of that has meant extremely rapid capacity growth even by regional airline standards. Between 2000 and 2004, Republic’s ASMs grew at a compounded annual rate of 50.2%. Its revenues have multiplied six–fold, from $88.3m in 1999 to just under $541m last year.

Republic is currently the fifth largest US regional airline in terms of 2004 revenues, behind ExpressJet ($1.5bn), SkyWest ($1.2bn), Mesa ($897m) and Pinnacle ($635m). At year–end, it operated about 700 flights daily, serving 73 cities in 31 states and the Bahamas.

The ASM growth has been paralleled by strong and steady profit improvement in the past five years, helped by a transition from revenue–sharing to fixed–fee feeder agreements. In Merrill Lynch’s estimates, Republic earned a pretax profit of $66.5m in 2004, which would represent a margin of about 12.4% — among the highest in the industry (the actual results will be out on March 3).

Republic’s operating margins are much higher than those of other regional carriers mainly because it owns a larger percentage of its fleet (paying interest, rather than lease expenses).

Republic first filed for an IPO in early 2002, as Wexford wanted to recoup (and profit from) its 1998 investment and the airline needed funds to meet progress payments on RJs. However, it took the company more than two years to get there, in what reads like a chronology of everything that went wrong in the US airline industry in that period.

Like Pinnacle, Republic was unable to proceed in the wake of ExpressJet’s disappointing market debut in the spring of 2002. The IPO was relaunched that summer but had to be withdrawn due to poor market conditions and key partner US Airways' first Chapter 11 filing. A third attempt, made in late 2002 just two days after US Airways secured DIP and equity funding, failed because of the Iraq war and uncertain industry prospects. In the autumn of 2003, when market conditions were ideal, Republic was in the middle of pilot contract talks and had no longer–term growth in feeder contracts.

Finally, in May 2004, Republic successfully went public despite a relatively weak market.

The IPO accomplished several important goals. The company raised $75m in gross proceeds and obtained a listing on the Nasdaq under the symbol "RJET".

It was able to repay Wexford fully ($20.4m) and boost its cash position to $42.9m at the end of June 2004, from just $1.2m three months earlier. After the IPO Wexford retained a controlling 74% stake in the company.

At the IPO price of $13, that stake was worth $247m — quite a return on a $20.1m investment.

Secondary share offering

In early February Republic completed a secondary offering of 6m shares, with Merrill Lynch, Raymond James and UBS as underwriters, again raising $75m in gross proceeds.

The offering was increased in size by 1m at the last minute and could raise another $11m if the over–allotment option is exercised fully.

The offering, which came soon after the expiry of the 180–day lockup period after the IPO, seemed very purposefully timed.

It was launched immediately after US Airways clinched important labour and financing deals that should enable it to survive at least another year, while waiting longer could obviously have meant potential investment opportunities disappearing at US Airways and Independence Air. The prospectus listed "potential strategic acquisitions and/or investments" as one of the possible uses of the proceeds.

However, contrary to some suggestions that Republic is now flush with cash to spend on acquisitions, the secondary offering merely restored its formerly relatively weak cash reserves to a healthy level (which is not to suggest that it could not afford acquisitions).

Cash and short–term investments have more than doubled from the September 30 level to about $134m, which is 27% of annual revenues — similar to Mesa’s but much lower than SkyWest’s 48%. The latest share offering reduced Republic’s lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio by a few percentage points to 84%, which is similar to the regional carrier average.

The offering reduced Wexford’s stake to 61.2%, or 59.5% if the over–allotment option is exercised. Despite the inevitable concerns about the size of that holding, as well as potential conflicts of interest (Wexford owns turboprop operator Shuttle America and is likely to invest in other airlines), Wexford’s backing is viewed as a very big positive in the current aviation environment.

Business strategy

Republic’s business strategy is an eclectic mix of the fixed–fee regional airline model, some key concepts adapted from LCCs and many unique strategies developed by the talented management team.

At a time when other regional carriers are considering going independent or returning partly to revenue–sharing, Republic wants to be a pure 100% fixed–fee operator. To diversify risk, it seeks to build relationships with a diverse group of airlines. Like LCCs, its key goals are to maintain extremely low operating costs and a well–trained, highly skilled and motivated workforce.

The unique aspects of the strategy include moving aggressively into 70–seat RJs and developing subsidiary platforms for different RJ sizes.

- 100% Fixed-fee operation Republic has been 100% fixed–fee since 2002. The benefits of the "fixed–fee" or "fee–per- departure" feeder agreements are well known: effectively eliminating the regional carrier’s exposure to fluctuations in fuel prices, fares and load factors. Some 58% of Republic’s costs are fully compensated for by its partners, including fuel, aircraft ownership, landing fees and insurance.

The agreements generally provide for minimum aircraft utilisation levels and include an agreed profit margin, which Republic can exceed if it can reduce costs below contractually agreed levels. The agreements facilitate a healthy revenue stream and a high level of earnings stability.

However, United’s bankruptcy has shown that the fixed–fee model does not work so well when a major carrier is in financial trouble.

Once in Chapter 11, the legacy airlines can reject the long–term feeder agreements and demand new ones that incorporate rate reductions. The new contracts have invariably meant reduced profit margins for the regional carriers that retain the business.

The best–positioned regionals in this new environment are obviously the lowest–cost operators, which can accept the rate reductions and still make decent profits. In that regard, Republic is probably the ideal candidate to continue to focus on the fixed–fee business. However, it obviously also makes sense to go some extra way to try to diversify risk.

Republic has disclosed in SEC filings that, over the past couple of years, it has granted some type of economic concessions even to its solvent partners, including America West, American and Delta. However, it has invariably negotiated something in return.

For example, in October 2003 it granted American a temporary reduction in monthly fees, in exchange for an extension in the date of American’s early termination right.

And in December 2004 it agreed to reduce Delta’s payments on ERJ–145s by 3% through 2016, in exchange for Delta extending the term and cancelling previously issued warrants for 2m shares.

Of course, the original decision to grant Delta the warrants was the equivalent of granting concessions or providing incentives to attract the business. As Republic explained it in last month’s prospectus: "To induce Delta to enter into the code–share agreement with us, we paid Delta a contract rights fee in the form of a warrant to purchase shares".

Examples like that illustrate that, among various other important attributes, Republic may have more imagination and aptitude than the other regionals to do what it takes to attract new growth.

- Lowest-cost producer It is hard to compare regional airline operating costs, but most analysts believe that Republic’s CASM is probably the very lowest. According to the IPO roadshow presentations, discussed by Raymond James analyst Jim Parker in his August 2004 report, Republic’s 2003 CASM, including interest costs, was 10.5 cents — the lowest among seven RJ operators, whose CASM ranged between 12.1 cents (Mesa) and 16.1 cents (Independence Air). Significantly, Republic has reduced its CASM by about 25% since 2001.

Republic believes that its cost advantage is due to four factors: low overhead costs, high labour productivity, high aircraft utilisation and a single fleet type. According to the latest prospectus, the low overhead costs arise mainly through flying for different partners (spreading overheads over a larger base) and operating in a geographically concentrated region.

The latter basically means eastern US — Republic flies for American at St.

Louis, for US Airways at the key Northeast cities plus Indianapolis, for Delta in Florida and for United at Washington Dulles and Chicago. It enables the airline to "leverage our maintenance and crew base overhead and cross–utilise our employees and also improve the scheduled efficiency of our aircraft".

In contrast, some other regional airlines (such as Mesa) operate for different partners in different, far–flung corners of the nation. Republic has indicated that, to avoid potential conflicts of interest with its strategy, it would consider operating for different partners under different subsidiaries.

Republic pays competitive wages and incentives in exchange for high productivity rates. Labour productivity is high also due to fleet commonality and lack of unproductive work rules.

Average aircraft utilisation, at 10.5 hours per day in 2004, is among the highest in the regional airline industry. Republic said that its agreements with the major airlines include incentives for the partners to increase utilisation.

One reason explaining the strong profit growth is that the airline was able to move quickly from a 33–strong turboprop fleet at year–end 1999 to an all–jet fleet by the end of 2002. It operated an all–ERJ–145/140/135 fleet until October 2004, benefiting from LCC–style efficiencies in crew training, aircraft maintenance and spare parts inventory associated with a single fleet type.

Such benefits will be retained, because the plan is to operate the 70–seat EMB–170s in a separate subsidiary — somewhat confusingly called "Republic Airline" — once it obtains an operating certificate.

- Move to 70-seat RJs Alongside with its low cost levels, Republic’s greatest competitive strength is its early move to 70–seat RJs. It is so far the only EMB–170 operator among the independent regionals, having introduced the type into Chautauqua’s United Express fleet in October. By year–end Republic had received 11 EMB–170s out of a total of 100 ordered and on option. Significantly, the company has the right to convert the options for the 100–seat EMB–190s, which have a high degree of commonality with the EMB–170s.

Aircraft in the 70–90 seat category represent the next major growth area for regional airlines. There are still pilot scope clause issues, but things are moving in the right direction. Some analysts have suggested that JetBlue’s introduction of the EMB–190 later this year could spur the legacies to press for scope clause relaxation to accommodate that aircraft.

- Single-fleet platform Republic has to operate the EMB–170 in a separate subsidiary to avoid scope clause issues. American’s pilot contract prohibits the carrier from using regional airlines that operate larger than 50–seat aircraft.

Consequently, the plan was to operate the United EMB–170s at Republic Airline right from the outset (originally from August 2004), with Chautauqua continuing to operate the 50–seat RJs.

However, Republic Airline has still not completed the certification process — the current expected date is June 2005 — so the company has had to negotiate a special arrangement with American. Under the deal, Republic paid American $500,000 through February 19 and will pay $1.1m through April 22 for the temporary right to operate up to 18 EMB–170s for United through Chautauqua. It will not be able to start flying the EMB–170 for Delta this summer if Republic Airline is still not certified.

Prospective start–up airlines be warned — even the seasoned Republic executives found the certification process "lengthy and complicated". They evidently significantly underestimated the difficulty of obtaining a new airline certificate.

Growth prospects

Assuming that all will go well with the Republic Airline subsidiary, the company has exciting growth lined up through 2006. The plan is to expand the fleet from 111 aircraft at year–end 2004 to 139 by the end of 2006. All 28 new additions will be EMB–170s under firm contract for United and Delta.

The United firm orders currently cover 23 aircraft through this June, while the Delta orders cover 16 aircraft through mid–2006.

The new Delta agreement in December was significant in that it gave Republic its first fleet growth in 2006 (the only other US regional that currently has growth beyond this year is ExpressJet). It also helped reduce exposure to US Airways, which last year accounted for 43% of Republic’s revenues.

The Delta deal followed expanded scope relief — the 70–seat RJ limit was raised from 58 to 150 aircraft. On a less positive note, Delta wanted out of eight 50–seat RJs that were due this year.

US Airways' troubles have kept a firm lid on Republic’s share price since the IPO.

While that may not change, the late–January lifelines that were extended to US Airways certainly removed much of the immediate concern about the fate of the 35 50–seat RJs that Republic currently utilises for its largest partner. Now it even seems plausible that US Airways could emerge from Chapter 11 by the June 30 target date agreed with creditors.

However, US Airways still has much work to do, not least of all to find more equity capital, and it is possible that it may need to sell some assets. Jim Parker suggested in a February 23 report that Republic is actually in negotiations with US Airways to purchase assets, such as some of the 25 owned EMB- 170s, which it could operate for other legacy carriers. Parker also said that be believed Republic would insist on US Airways affirming its existing feeder contract as part of any deal reached.