CSA, Malev and LOT: the EU opportunity/threat

March 2004

The European Union’s expansion on May 1, 2004 brings in 10 new members, eight of which are from central and east Europe.

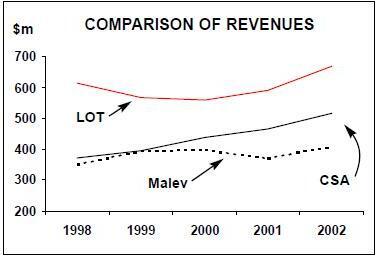

The three largest airlines from these new entrants — CSA, Malev and LOT — face both opportunity and danger from their countries' membership of the EU and the European Common Aviation Area (ECAA).

Having already been through one major change — from operating in Soviet command economies to the western capitalist model — how will they now cope with the liberal aviation regime of the EU and the LCC threat?

CSA Czech Airlines

Following the peaceful partition of Czechoslovakia into the Czech and Slovak Republics in 1992, CSA has emerged as one of the stronger airlines in Eastern Europe.

As the Czech Republic already has a relatively liberal air services regime and a small domestic market, CSA could also benefit by gaining access to the eastern and central European markets it has previously found difficult to penetrate — Poland and the Baltic countries.

Access to nearby markets would be of particular benefit to CSA’s declared strategy of developing Prague as a key hub, particularly for SkyTeam traffic into eastern and central Europe. Since joining the SkyTeam alliance in 2001, CSA has experienced significant increases in traffic, and the airline wants to keep developing Prague as SkyTeam’s gateway to the east.

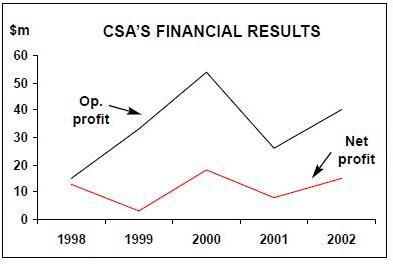

In 2002 CSA posted an operating profit of $40m and a net profit of $15m, both substantially up on the results for 2001, despite severe flooding in Prague in August 2002 that affected both leisure and business traffic. In the first half of 2003 CSA made a net profit of $4.1m, based on a 6% rise in passengers flown (although load factor fell by 2% due to an increase in capacity through fleet additions).

For full year 2003 CSA saw a 17% increase in passengers carried to 3.6m, though CSA will do well to beat its 2002 net profit figure.

CSA’s fleet comprises three A310s, 23 737–400/500s and nine ATR–42/72s, and the airline is considering renewal options for its Boeing and Airbus aircraft at the moment. On long–haul, the likely replacements for the A310s are A330s or 767s, which would be used primarily on routes to the hubs of SkyTeam alliance partners.

For medium–haul, the 737 300/400s will be replaced by an order for up to 40 737NGs or A320 family aircraft over the next decade, with the first deliveries needed in 2005. Given Boeing’s existing close relationship with CSA, the 737NGs should be the hot favourite.

However in the defence sector, Boeing has left a strategic partnership after a rocky six–year collaboration with fighter manufacturer Aero Vodochody amid accusations by Czech politicians that it "failed to deliver".

Perhaps of more significance is the Czech Republic’s imminent entry into the EU. What better way to ingratiate yourself with your new political and economic partners than by encouraging your national airline to place a major aircraft order with the continent’s sole manufacturer? CSA is giving nothing away at the moment — a tender was issued to both Airbus and Boeing at the end of last year, and CSA is reportedly in detailed discussions with the manufacturer sover an initial order for 15–20 leased aircraft.

On short–haul, CSA operates nine ATR42s and ATR 72s, and has another seven ATR 42- 500s on order — three due for delivery this year and the others in 2005. The ATRs provide regional feed into the Prague hub, which is becoming a key battleground for CSA as it tries to fend off increasing attention from low cost carriers. LCCs such as easyJet and bmibaby are eager to capitalise on the growing demand for leisure travel into Prague, largely from western European countries such as the UK and Germany.

CSA is keen to develop low–cost operations of its own, particularly eastwards and in line with its gateway strategy at Prague.

Initially CSA considered buying a LCC, but in February 2004 CSA suspended longstanding talks with potential acquisition Travel Servis, a Prague–based charter airline with a fleet of five 737s. Negotiations were halted as Travel Servis announced its own plans — it will launch operations in May under the brand SmartWings. Unless another acquisition candidate is found, CSA will launch its own LCC sometime in 2004, it is believed.

Privatisation?

The Czech state owns or controls more than 90% of CSA, and privatisation has been on the agenda for a number of years. However, most observers believe it will be 2005 at the very earliest before an IPO is carried out. The government will be keen to avoid the fiasco of the early 1990s when the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development became a shareholder in CSA and the airline signed a strategic alliance with Air France. Just two years later, the "grand alliance" collapsed, and the two external stakes were resold to Czech state interests.

Privatisation largely depends on another couple of years' strong financial results at CSA, and to this end the Czech government replaced Miroslav Kula as CSA CEO with former Czech defence minister Jaroslav Tvrdik in September 2003.

Though Kula had been CEO for four years and had done well, he faced major problems last year with the airline’s staff. In 2003 CSA attempted to impose a single collective working agreement on its workforce, a move strongly resisted by the unions. Pilot union CZALPA threatened strike action, but at the last moment — in June 2003 — a compromise was reached under which it was agreed a collective agreement on broad terms and conditions would be accompanied by separate agreements with the seven main unions at CSA on specific details that affected their members.

But just a month later management became embroiled in yet another clash with workers after making four mechanics redundant — a move that mechanics union OOLM said was intimidating given the ongoing talks over the collective and separate working agreements. Until these agreements are completed, relations between the management and unions will continue to be strained.

But Kula’s departure may also partly be due to the government wanting a new face in charge as the country prepared for EU membership in 2004. The Czech press reported that the government wants CSA to become more "dynamic" in the face of increasing competition from the LCCs.

Kula wasn’t the only person to go — the entire board went as well, to be replaced by a new nine–person strong senior management team. It is now looking at CSA’s strategic options, and a new plan for 2004–06 was presented internally at the end of February, though it will not be unveiled formally until the summer.

It is reported that the new management is looking closely at CSA’s costs — which it believes are too high for an airline of its size — as well as labour productivity. Though costs are lower in the Czech Republic (and other eastern European countries) than western Europe, the legacy of command economies is a raft of business regulations that ramp up the cost base. Steps have already been taken — in November 2003 CSA reduced travel agent commission from 7% to 4%, giving agents less than two weeks' notice. As for labour costs, the Czech Republic’s entry into the EU is raising wage expectations among many sections of the economy, and this will provide a real test to CSA’s new management.

Malev Hungarian Airlines

Like CSA, Malev underwent a change of leadership in 2003 at the instigation of its government owner, with Laszlo Sandor taking over as CEO and chairman in May.

Sandor came from the state water company and became Malev’s fourth CEO in as many years — an indication of the problems facing Hungary’s national airline.

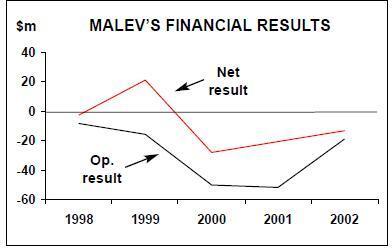

The Hungarian government acted despite Malev managing to reduce its net loss to $12.8m in 2002 from a $21m loss in 2001 following a major restructuring and route expansion programme carried out by Sandor’s predecessors, CEO Jozsef Varadi and chairman Andras Huszty.

Indeed at the end of 2002 management forecast a profit for 2003, based on a 5% rise in fares, increases in capacity and the implementation of a five–year strategic plan based around the airline joining a global alliance, obtaining a capital injection and becoming "commercial". Management was optimistic following a 2002 that saw Malev carry 2.2m scheduled passengers — 1% up on 2001 — and with a 3.6 point rise in load factor to 63.1%.

But the strategic plan soon ran into trouble, and the Gulf War led to a 20% drop in passengers carried. A cost–cutting programme was introduced with the aim of saving more than $4m a year, but the government decided more urgent action was needed and management was replaced.

Allegations of an improper audit tendering process at Malev played a part in the decision, it is believed, but the government was also keen to get a new management team in place ahead of another attempt at privatisation.

Through the privatisation agency APV, the Hungarian state owns 97% of Malev, but it is keen to offload a majority stake. A previous privatisation attempt in 2001 failed after little enthusiasm from potential investors was found.

Like CSA, Malev attempted an equity alliance with a western carrier following Hungary’s emergence from the Soviet Bloc in the early 1990s. Then Alitalia purchased a 35% stake but — like CSA/Air France — the linkup was entirely unsuccessful, and Alitalia divested its stake in 2000 as a minor condition of its state aid injection. This time around a successful IPO or the finding of a potential acquirer will depend on a significant improvement in financial results, a task made harder by the fact that net losses are expected to increase to around $30m in 2003.

The continuing losses are due partly to Malev’s extensive route network, which includes North America, Asia, Africa and the Middle East — indeed Malev’s exposure to the latter market was a serious disadvantage during the Gulf War.

Few of these long haul routes are thought to be profitable, and to make matters worse some of Malev’s regional routes in Europe struggle to make a profit as well.

Despite this, Malev launched four new routes out of its Budapest hub in 2002 (to Odessa, Timisoara, Bologna and Venice) and three more in 2003 (to Pristina, Split and Geneva).

However, there is expectation that some of the loss–making routes will become profitable as new equipment is introduced.

Malev operates a fleet of 26 aircraft, and in January 2003 Malev received the first of 18 737NGs it is leasing from ILFC to replace earlier 737 models and Fokker 70s, whose leases expire in 2003 and 2004. Eight aircraft are outstanding, and they will arrive over the next two years, which will then give the airline one of the youngest fleets in Europe. On long–haul, Malev has just two 767–200ERs, and the airline has begun the process of finding replacements.

For short–haul, the government provided loan guarantees to the European Investment Bank for Malev’s purchase of four Bombardier CRJ–200ERs that were delivered in 2003.

Six more CRJ–200s or -700s are on option.

The CRJs are flown by Malev Express, which was launched in July 2002 as an operator of regional routes and a feeder carrier into Budapest. Budapest appears key to the future of Malev, though the airline’s attempts to turn the airport into an east–west hub may be difficult to achieve given similar ambitions for Prague by CSA. And competition will grow at Budapest anyway. The first LCC in the region — Bratislava–based SkyEurope has established itself as Eastern Europe’s first genuine LCC, operating a fleet of three 737- 500s and six Emb 120s from its main base in Bratislava, Slovakia.

With aggressive and competent management, under Chairman Alain Skowronek and CEO Christian Mandl, SkyEurope has expanded by setting up a second base in Budapest, flying to London, Paris, Amsterdam and Rome and is now targeting Poland.

Alliance need

Malev feels the need to sign up with a global alliance, as do all the Eastern European airlines, though whether this is in expectation of real commercial benefits or simply a desire to have a Western stamp of approval is unclear.

Malev is the only one of the three major central/east European carriers not to be part of a major aviation alliance.

Indeed part of the reason CSA joined SkyTeam in 2001 may have been due to concern that SkyTeam might link up with Malev instead. LOT is part of the Star alliance, which also includes Austrian Airlines, a carrier with large network in eastern and central Europe.

Oneworld also appears happy with Finnair and Swiss’s coverage in the region, leaving little option for Malev but SkyTeam. Malev has close ties with SkyTeam’s KLM, with which it started code–sharing in 2001, and in early 2001 talks between Malev and CSA on general co–operation led to speculation about the intriguing possibility that Malev could also join SkyTeam as well. This was confirmed in January 2004 when CSA became an official "sponsor" of Malev in negotiations to join SkyTeam.

Whether Malev would join as an associate or full member of SkyTeam is unknown, but a formal link appears probable unless there is last–minute interest from oneworld.

Strategically, having two central/east European members of SkyTeam is rather difficult to justify, even though Malev is stronger towards the southern part of Eastern Europe and CSA has a larger route network to the north. A tough decision may have to be made about whether two east–west hubs — Prague and Budapest — are sustainable.

Sacrificing Budapest in favour of a SkyTeam east–west hub at Prague would be a hard decision for Malev, but probably a price worth paying in exchange for the passenger uplift and security that joining SkyTeam would bring. And membership of a major alliance would be a timely boost ahead of a renewed privatisation attempt.

In order to improve both its privatisation prospects and attractiveness to SkyTeam, Malev’s new management unveiled a major restructuring plan in December 2003, designed to cut costs by $37m a year and put Malev back into the black for 2004.

The programme includes reduced capex (now that the medium–haul fleet renewal is almost complete), greater use of direct distribution and staff redundancies.

The latter may be particularly difficult to achieve given the difficulties caused by earlier redundancies, made in 2001. There was serious strike action in February 2002, and action by flight attendants over daily allowances was narrowly avoided just over a year ago only after the airline agreed to a 15% rise in allowances in return for a similar increase in hours flown.

But management’s ability to avoid union trouble may be strengthened by redundancy payments derived from the final cash injection by the Hungarian government that will accompany the current cost–cutting.

The state is giving F10bn ($46m) as a final handout before the country’s entry into the EU in May.

It’s unlikely that this will be the last major cash injection that Malev will need — but once the airline is privatised this burden will then rest with the private sector.

LOT Polish Airlines

LOT underwent a traumatic period in 2003 after CEO and president Jan Litwinski resigned suddenly in March following media speculation that LOT board members had been paid "extra salaries" by shareholder Swissair. Litwinski had been CEO since 1992, but his departure was followed by the other board members in April as the Polish government decided to appoint a fresh management team.

Marek Grabarek, an executive from the Polish state treasury, replaced Litwinski on an interim basis but this appointment was met with dismay by LOT’s unions, who threatened to strike if someone so closely associated with the Polish government was appointed as CEO. The Polish government ignored the unions and in June appointed Grabarek permanently, with a remit to cut costs and establish the airline as a consistently profitable airline ahead of a further sell–off of the state’s shareholding.

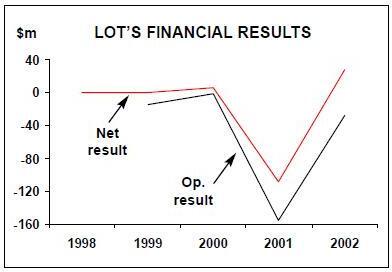

LOT racked up a substantial operating loss of $155m in 2001, which resulted in a raft of cost–cutting measures that reduced the loss to $27m in 2002, helped by a 5% rise in passengers carried to 3.9m, with load factor rising by eight points to 70%. In the first–half of 2003 LOT made an operating profit of $2.3m, and for full–year 2003 LOT is expected to report a small operating profit.

During 2003 LOT experienced sluggish long–haul traffic, though short- and medium–haul traffic is believed to have been much better.

Although the trend is in the right direction, the improvement appears not to be enough for the government, which recently announced that a float or trade sale is not on the agenda for LOT for the next two or three years. The Polish government sold a 10% stake in LOT to the SAirGroup in 1999, which increased its share to 38% in 2000, though was diluted down to 25% following a capital injection by the state in 2001. The government now owns 68%, with employees holding the remaining 7%.

Further privatisation is complicated by the fact that LOT is more than just an airline — it owns stakes in many other diverse companies, such as a casino company and a horseracing concern — but the Polish government would like to reduce its stake to 51%.

But before a 17% tranche is sold, not only do LOT’s results have to improve but also the fate of Swissair Group’s 25% shareholding has to be resolved. This stake is currently with Swissair’s administrators, and one airline reportedly interested in acquiring it is SAS, which is keen to extends southwards its dominance in Scandinavia and the Baltic region (SAS owns 47% of Air Baltic and 49% of Estonian Air). As SAS and LOT are both Star alliance members, the deal would make sense, though there are other contenders for Swissair’s stake in LOT, including Lufthansa, which also code–shares with LOT and was the prime mover behind LOT’s membership of the Star alliance.

Star move

LOT’s entry into Star in October 2003 gave the Polish airline a psychological uplift, and LOT predicts that the combination of Poland’s EU entry and the admittance of LOT into Star will boost business traffic 10%, and developing high margin business traffic is a key priority for LOT over the coming year. LOT hopes that Warsaw will be developed within Star as an east–west hub, though whether this is a realistic prospect long–term is open to doubt.

Instead, LOT may become no more or less than a north European feed airline into Lufthansa’s hubs, a prospect that LOT’s management is keen to dismiss.

Star entry didn’t come cheap for LOT. The airline had to abandon code–share deals with oneworld members British Airways and American, but these were replaced by deals with BMI British Midland and United, the latter giving LOT code–sharing on flights to 29 beyond–gateway destinations in the US.

Interestingly, this is a one–way deal at present, as United code–shares to Poland with other Star members.

Currently LOT operates a 36–strong fleet. For long–haul, LOT uses two 767–200ERs and two 767–300ERs, and for medium–haul it has 17 737–3/4/500s. A decision on replacements for both categories is expected soon, and LOT is likely to choose a single manufacturer.

The choice is between 737NGs/767- 400s/7E7s and A320/330s, and again, like CSA, Boeing’s track record with LOT may be balanced by the Polish government’s wish to appear at the heart of the EU — although Poland’s political ties with the US administration should not be discounted (and Chicago, Boeing’s management HQ has a very strong Polish influence). Negotiations with manufacturers are due to begin any time now.

In May 2003 LOT ordered 10 Embraer 170s, the first of which was delivered in January 2004, with the order due for completion in 2005. Some of these will be used for new routes, such as from Warsaw to Dublin and Venice. Eleven other aircraft are on option, though these can be 170s or 190/195s.

Regional feed is provided by subsidiary EuroLOT, which was launched in 1997 and now operates a fleet of eight ATR 72–200s and five ATR–42s on mostly loss–making domestic routes.

This fleet renewal is part of the strategy to improve the Warsaw hub. Domestic passengers account for 20% of all passengers flown by LOT, intra–European 55% and transatlantic 13%. However, approximately 60% of domestic LOT passengers transfer onto international services, and LOT has a 50–55% market share of international traffic out of Warsaw.

That’s a market position that other airlines are keen to erode. Poland is the largest of the 10 countries joining the EU in May, and with a population of 39m the country is a key target for both LCCs and other national European airlines.

At present, the foremost LCC threat comes from Air Polonia, which under ex–LOT CEO Jan Litwinski has turned itself into a low cost operator. The airline operates two 737- 400s, but has plans for further aircraft after launching routes in December 2003 between London Stansted and Warsaw, Poznan and Katowice and domestically on Warsaw- Wroclaw and Warsaw–Gdansk.

SkyEurope, as mentioned above, intends to add Poland (Warsaw and maybe Katowice) to its Slovakian and Hungarian–based operations. Another Polish LCC is GetJet, a subsidiary of Silesian Air that started operations in February 2004. Also Wizz Air, headed by Joszef Varadi, ex–CEO of Malev, has ambitious plans for an A320 operation based at Katowice, flying from Krakow and also Budapest in the future.

After initially dismissing the threat of Air Polonia and the LCCs, in December 2003 LOT reacted by introducing a raft of low fares on domestic routes out of Warsaw — a signal that it is facing up to the reality of the LCCs.

What a long–lasting fare war will do to 2004’s financial results can’t be judged yet, but the imperative for LOT’s new management is to keep the airline in profit. Despite the boost of joining Star, finances are tight.

In July 2003, LOT took out a $70m loan from a consortium of eight Polish and East European banks in order to refinance an earlier share issue but, like its east European neighbours, LOT would greatly benefit from a substantial injection of fresh equity.