LCC growth: implications for the suppliers

March 2003

The growth of Low Cost Carriers (LCCs), is affecting many areas of the industry: consultants at AeroStrategy have examined the implications for the LCC’s suppliers.

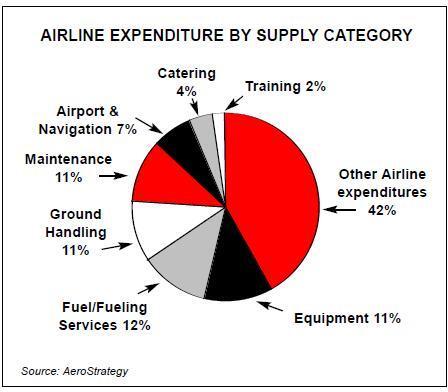

Suppliers are here defined as original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and suppliers of the major aviation service categories that account for just over half of a typical airline’s expenditure (see chart below).

OEMs

An important implication for OEMs is a changing fleet mix with an increasing requirement for short to mid–haul narrow bodies. AeroStrategy’s fleet forecast model predicts that the 737NG and A320 family aircraft together will grow from 21% of the fleet today to 34% in 2013. The LCC market tends to be an "all or nothing" opportunity.

These carriers stick with one type of equipment, be it an airframe, engine or component system. This focus on a single type, combined with the scaleability of their business model, means that the most successful LCCs can become very significant customers in a relatively short period of time. Witness Ryanair’s 250 orders and options for Boeing aircraft since January 2002. This will force OEMs to make significant bets and take a long–term perspective. The easyJet decision to buy Airbus in addition to Boeing is an exception and most LCCs are unlikely to follow.

Other than low price, what do LCCs seek from OEMs? The imperative of high asset utilisation means that OEMs must place a strong focus on aircraft availability and reliability of equipment, spare parts supply and technical support.

The imperative of simplicity and the propensity of LCCs to outsource means that support in training, spares, logistics and maintenance services has to be world–class. Some OEMs, and in particular Airbus and its vendors with their entry into the European LCC market with easyJet, will have to step up to the mark. With the growth of the LCCs, the OEMs product support network and product will become even more important — and will itself have to be scaleable.

The OEMs must also not forget their core customers — the majors / flag carriers. While the traditional airlines seek to learn "low cost" lessons from LCCs (e.g. higher aircraft utilisation), they will continue to need to differentiate and redefine their product.

This is particularly important as they strive to attract back the business traveller and develop new value propositions. The cabin product and environment will be a key area of attention for all OEMs.

Ground handling

LCCs should be good news for ground handling suppliers, as they generate movements, passengers and generally outsource this activity. The winning suppliers will be those who can simplify and adapt their processes to the very tough demands of a high utilisation, short turnaround environment. Furthermore, one of the key value propositions marketed by the new "global" ground handling companies such as Swissport or Penauille is a single source, common standards service proposition. This should be an ideal match with LCCs if this supplier model is indeed correct and can be delivered.

The challenge is to demonstrate the value of a network approach and convince carriers not to shop for the best rates by airport.

Additionally, the current turmoil may be a one–time catalyst for major airlines to outsource this labour intensive, non–core business activity — particularly in the United States. US majors employ tens of thousands of ground handling employees and should not ignore the cost reduction opportunity represented by this large pool of relatively unskilled labour.

Maintenance

Like ground handling, maintenance suppliers should benefit from the growth of LCCs given their tendency to outsource.

They are under no illusion whether or not extensive maintenance capability is core to the airline: it clearly is not.

This means they are more dependent on their maintenance suppliers than typical customers, as they demand services such as component management, technical services and planning support.

The reason that easyJet has an engineering organisation of less than 10 managers is that it has long–term "full support" contracts in place, including the unique easyTech concept that provides third party yet dedicated line maintenance and maintenance control. This is not to say that LCCs will outsource all maintenance activity: even Southwest finds it necessary to perform line maintenance and airframe "C" checks to maintain desired levels of dispatch reliability and operational flexibility.

Does the low cost focus imperative mean that LCCs will invariably choose the lowest price supplier? Not necessarily.

Their focus is on high asset availability and productivity, and life–cycle costs are important. Suppliers need to demonstrate how they will deliver the optimal blend of reliability, flexibility, quality, support and performance to win LCC business. In some cases this will benefit independent suppliers, in other cases OEMs and airline maintenance organisations.

All suppliers should anticipate aggressive negotiation on service levels for aircraft availability and reliability, and on total price.

Finally, a real challenge for maintenance providers is to grow with the carrier. The services required are not new but they have to be delivered to customers with increasing size and the highest demands for low costs, responsiveness, efficient processes and incentivised performance.

Fuelling services

The lions' share of expenditures in this service category is for fuel, the supply of which is virtually totally dominated by the oil companies. This will not change. But what are the implications for into–plane fuelling services? In Europe and Asia the oil companies also dominate this part of the fuelling supply chain. The cost benefit of unbundling into–plane services from fuel supply only becomes substantive when an airline has significant scale.

So it will be a while until any of the European or Asian LCCs reach this point. Meanwhile, the LCCs will impose high demands on their into–plane suppliers as they continue to focus on short turnarounds.

The incumbent oil companies need to satisfy this requirement or face losing business. In contrast, in the United States the oil companies are generally "off–airport" and into–plane services are provided by independents such as ASIG or by the airlines themselves. The most important observation here is that the US airline recession could be a catalyst for some US major airlines to re–examine the necessity of their in–house into–plane fuelling capability.

Airport and navigation

Airport business models have become increasingly commercial in recent times and competition between airports has grown.

LCCs have important implications for this supplier group. First, LCCs have shown they can generate new traffic and significant growth — hence they provide new opportunities for regional and local airports. Examples abound, from the impact of Southwest Airlines at Baltimore Washington, JetBlue at Long Beach, and Ryanair at multiple secondary and even tertiary airports.

A second implication for airports is that LCCs are in some instances using their negotiating leverage to achieve lower landing fees, traditionally a sacred cow of controlled costs. Ryanair’s success in this area with several European airports is well known. However, with the world’s top 50 airport groups showing a comfortable net margin of 11% in 2001, while the top 50 airline groups averaged a 4% net loss, the issue of airport charges has moved to the front burner for airlines.

What about navigation services? This is not an area of expenditure where airlines have a lot of choice or much opportunity to negotiate on charges. However, once again, an LCC is taking a lead and Ryanair is now actively campaigning for greater accountability and charges based on achieving appropriate service standards.

Catering

LCCs are generally bad news for the catering suppliers, as their emphasis on simplicity reduces catering demand. In contrast to major airlines that spend 3–4% of their budget on catering services, LCCs typically spend less than 1%. Clearly, they are not a major growth opportunity for catering suppliers, which will need to focus on large, long haul airline customers and help them to redefine and improve their product and value–add to the passenger.

Training

Again, LCCs are natural out–sourcers that provide business opportunities for training suppliers. And many of the larger airlines have also recognised that they do not need to own and manage very expensive flight simulators. These trends have already resulted in increased outsourcing and a consolidation of supply, with the simulator OEMs aggressively expanding into this market.

Traditional practice in pilot training is to buy in simulator time but in the interests of quality and operations and safety standards, use in–house instructors. LCCs are again innovators in this area — easyJet this time, with its unique relationship with CTC, where the latter provides instructors not just for the classroom and the simulator, but also for recurrent and line training.