Can TAP Air Portugal survive long-term?

March 2003

2003 is a vital year for TAP Air Portugal. The Portuguese government hopes that an airline that has struggled to adapt to a subsidy–free existence, will complete a successful privatisation, transforming itself from a sleepy, third–tier European airline into a profitable carrier that can survive tough competition.

But is TAP Air Portugal a worthwhile investment, or — regardless of ownership — will the airline only ever be on the periphery of Europe’s aviation industry?

Portugal’s flag carrier was founded in 1945 and since nationalisation in 1975 it has remained firmly in the grip of the state.

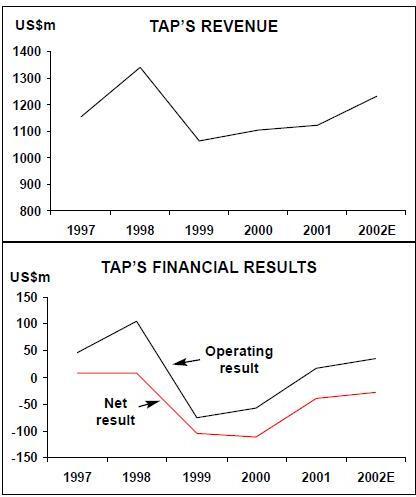

As with other state–owned airlines in Europe, whenever TAP’s finances became precarious the government was more than happy to step in and give or loan large amounts of state aid, particularly in the mid–1990s. In 1997, however, this all changed when the Portuguese government decided it had no choice but stop the subsidies.

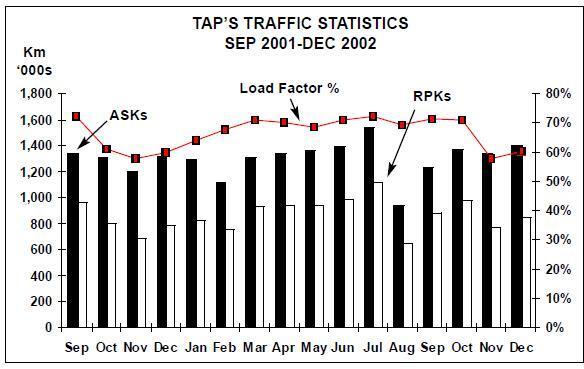

Not surprisingly, as the 1990s came to a close TAP started racking up substantial losses (see graph, right), and it soon became apparent that the future of the airline might be in doubt.

With further cash injections from the state ruled out, the Portuguese government decided an external saviour was needed. Unfortunately, the white knight that came to the rescue was Swissair, in retrospect just about the worst choice the government and its advisors could have made. In March 2000 Swissair promised to buy a 34% stake in TAP for just over $150m, an investment that would tie the airline into a major European player and secure its future for some years to come.

It didn’t turn out that way of course and the collapse of Swissair in 2001 was a severe blow to the airline and the government. Not only did TAP lose its financial saviour, but it also lost an important traffic feed from Sabena and Swissair flights, as well as its global airline alliance (TAP was one of the founders of Qualiflyer in 1998).

In the months after Swissair pulled out the Portuguese government searched frantically for a replacement Portuguese investor, but this effort was doomed once September 11 occurred (although, ironically, the attack was beneficial to TAP as passengers switched to it from other airlines).

To compound matters even further, the impending Portuguese general election of May 2002 precluded any restarting of the search for new investors in the first half of that year, so the airline had no alternative but to consolidate and focus on operational matters. In terms of finance, TAP arranged some short–term solutions.

In 2001 an existing $400m+ loan from the Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi was renewed for another two years, while in the summer of 2002 TAP arranged a €100m loan with PK Airfinance, a subsidiary of GE Capital, secured on three A340s in the TAP fleet. The European Commission no longer considers aircraft backed financing as being state–aid, but loans and aircraft remortgaging are only short- and medium–term expedients. The need to find firmer financing still existed for TAP,and the only real alternatives were, (and are), substantial new equity and/or positive cash flow.

In one sense, through 2002, the airline’s management knew that it only had to worry about short–term financing, as privatisation — the usual assumed panacea for troubled flag carriers — was always going to be revived by the government. Ideologically, the new centre–right government in Portugal was guaranteed to be keen on selling off the state’s assets, but in any case the EU’s Growth and Stability Pact forced the government to reduce its substantial deficit by all means possible.

The privatisation plan was therefore resurrected in the second half of 2002, with a completion date set for 2003. In late 2002, the government appointed Rothschild, Banco Portugues de Investimento and McKinsey to oversee the process. An initial trade sale of between 34–39% has been widely flagged as the preferred option, but sources suggest that a larger sell–off is also being considered. In principle the government would prefer to offload all the state’s stake anyway — but it also makes financial sense as it would get a much better price per percentage sold for selling a majority stake rather than a minority one. And as the government intends to use all the proceeds to reduce public debt, investors are going to have to dig deep again in order to find development finance — a move they are much more likely to do if they have a majority stake rather than a minority one.

TAP's assets

So what will investors get for their money? TAP currently serves 36 destinations in Europe, Africa and the Americas, using a relatively modern fleet. Operating thin long–hauls profitably is always a major problem.

TAP should be profitable on Angola where it has had little direct competition and benefits from a restrictive bilateral (though it will have lost connecting traffic as BA has resumed direct flights from London to Luanda). On Brazilian routes TAP should benefit from Varig’s parlous financial situation. The service to New York is probably operated for partly political reasons.

On the European network TAP’s challenge is to find a niche on scheduled routes to main cities and capture a good proportion of the business traffic. While TAP inevitably still benchmarks itself against other, mostly northern, AEA airlines, competition is increasingly coming from the LCCs and the scheduled subsidiaries of the charters, with which it cannot begin to compete on cost.

Ryanair, which previously had avoided the Iberian peninsula because of high airport charges, has now started flying to Faro from Dublin (as well as entering Spain at Girona–Barcelona airport).

Domestic competition comes from Portugalia. In existence for just 13 years, Portugalia today accounts for 20% of the Portuguese market, and this would be even higher if its expansion plans hadn’t been delayed by an aborted flotation in 1998 and the saga of a proposed sale to Swissair in 1999.

The latter was investigated by the European Commission on competition grounds, given Swissair’s links with TAP, leading to Swissair withdrawing its offer in August 2000 (which was fortuitous from Portugalia’s point of view, as it turned out).

Competition apart, the underlying problem is that Portugal’s market — whether measured by domestic or international traffic — is small when compared with almost all its rivals (the Portuguese market as measured by ASKs is a tenth the size of the UK market and a quarter the size of the Spanish market), and even smaller if business travel, a key profit driver, is considered. This home market weakness is a major handicap for TAP, and one that the airline’s management is stuck with.

So for the two years that Fernando Pinto, the TAP CEO, has been in charge, the airline has been making the best of its situation, and indeed its operational performance has seen significant improvement. Daily aircraft utilisation rates have increased by 30% over that period, with staff levels down by more than 10% (to just over 8,000) as part of a general drive to cut costs.

Yet by most criteria, TAP is still behind its European rivals. Productivity is still poor; with ASK per employee some 30–40% higher at TAP than the AEA average (although the gap has closed over the last couple of years).

There is still much work to be done, and some tough strategic decisions that the airline’s management has not taken (or, given its current ownership, cannot take). For example, capacity on some loss–making short–haul routes in Europe is too high. A new owner is likely to be ruthless in weeding out the loss–making routes and increasing capacity elsewhere, although in the short–term the scope for these moves will be constrained by the fleet mix.

All of TAP’s 38 jet aircraft are Airbuses of which eight or nine are on operational leases from the major leasing companies. The reliance on Airbus aircraft is a strategy that brings operational savings to TAP but makes it vulnerable to price creep from the European manufacturer.

TAP executives argue that this isn’t the case, and that they keep in close contact with Boeing all the time in order to keep the pressure on Airbus. However, this is not a current issue as TAP has recently completed a fleet revamp, replacing older A320s and 737s on short–haul routes with new A320 family aircraft, the last of which arrived in 2002. The long–haul fleet is more varied age–wise, with A310s and A340- 300s, and the A310s will be replaced at some stage. However, the current plan is that TAP will not place any new aircraft orders for the next two or three years — although it’s almost certain that this timeframe will change once the privatisation of TAP is completed.

When that happens, the need for more long–haul capacity to exploit under–served routes will most likely lead to an early decision between A330s and 777s, the leading candidates to replace the A310s. The TAP Group also has a ragbag of other airline investments that need to be rationalised.

They include a 51% stake in Yes Charter Airlines, which TAP launched in 2000 in partnership with Viagens Abreu, a Portuguese tour operator. The two–aircraft airline is loss making and a strategic distraction, although perhaps not as troublesome for TAP as its 15% stake in Air Macau, which it acquired in 1994. This latter investment is more to do with Portugal’s colonial past than with any serious traffic or financial strategy, and TAP withdrew its services to Macau when the territory was handed back to China in 1999. The Air Macau shareholding is held indirectly via a Macau–based company, and negotiations have been held with the Macau government (which is Air Macau’s major shareholder) over a graceful TAP exit.

A decision also has to be made on global alliances. Sensibly, TAP has decided not to rush in to any new alliance agreement as a replacement for Qualiflyer. Instead it has signed more than 10 code–sharing agreements, which keeps all TAP’s options open and, more importantly, does not preclude any airline investor from one of the global alliances.

The major code–sharing deal signed with Iberia in 2002 (to more than 20 destinations), has led many analysts to believe oneworld is the eventual destination for TAP, but the question cannot be resolved until the identity of the new investor is known. Conversely, TAP is dropping a code–share agreement with American Airlines from the end of March, but too much should not be read into this as the move is primarily due to TAP switching its sole North American route from JFK to Newark airport, where American does not have a strong presence.

Reported results for 2002 have been encouraging, and in the third quarter of 2002 (July–September), TAP recorded a 23% increase in net profits to $43.6m, with operating profit up 27% to $59.9m. In the January- September period, net losses fell by half to $21.8m, while operating profit rose 56% to $25.9m.

At the end of last year TAP claimed it was still on course to just about reach its target of a small net loss of around $5m for 2002.

However, it is probable that the loss will be slightly larger than that due to — among other things — the effects of the December general strike by workers across Portugal in protest against the government’s plan to erode laws protecting workers' rights.

It must also be remembered that TAP group results include not only the airline but also ground handling, maintenance and engineering units, the last three of which are profitable and hence mask a continuing loss for the underlying airline operations. (Tentative plans to sell–off ground handling have met union opposition, and in February, 3,000 TAP employees staged a protest march in Lisbon against any break–up of TAP’s business units).

Profits and strategic fit?

They key question, therefore, is whether TAP’s core airline operations can ever be profitable? The options for TAP’s current management and/or the new owners are limited.

Looking to 2003, TAP aims to shave another $30m off its cost base via initiatives such as a hiring freeze, but will this be enough? Headcount could be reduced further and loss–making routes axed ruthlessly, and it is feasible that this sort of action would make the airline profitable long–term — but only at the cost of angering the workforce and shrinking the airline to a size that guarantees it becomes a viable niche carrier on the margins of the European airline industry.

That may or may not be the best option for TAP, although whether the myriad of advisors to the government are likely to recommend this option now that the green light for privatisation has been given is very doubtful.

Indeed the very rationale for finding a trade buyer is that there must be some king of strategic fit between TAP and one of the European mega airlines, based around network complementarity.

Yet that may be a very dangerous assumption.

Virtually all of the potential European acquirers have deep troubles of their own at present, and the investment case for a major external acquisition at this stage would need to be very persuasive indeed. Just what exactly does an airline at the periphery of Europe and with debts approaching $1bn have to offer airlines such as Iberia, Lufthansa or Air France? Much has been made of the code–sharing agreement between Iberia and TAP, which many believe makes the Spanish flag carrier the front–runner in the investor race (if there is more than one interested party, that is).

Culturally there should be a close fit and Iberia has admitted it is studying an investment in TAP, but what would Iberia get from an equity link–up that it is not currently getting from a code–sharing deal? Theoretically, TAP’s and Iberia’s European networks could be rationalised while TAP’s long–haul flights could be redirected to Madrid, with a Lisbon–Madrid shuttle serving Portuguese O&D passengers.

Politically, redirection of flights from Lisbon to Madrid will not be appealing, even to a centre–right government. And of all Europe’s airlines Iberia has the strongest South American network anyway, so does TAP really have enough additional business passengers to make it worth Iberia’s while to spend at least $150m in securing them? The key to the privatisation may be TAP’s long–haul network, which contain some of the most and least profitable routes at the airline.

As a basis for setting up or enhancing an existing European–South America route network in competition to Iberia’s, they may be attractive, particularly for Air France. Yet in November 2002 Pierre Gourgeon, Air France executive director, said that the airline was not interested in investing in TAP, preferring instead to look at other opportunities. In any case Air France has recently extended a code–share agreement with Portugalia. And an investment by Lufthansa would be very problematical given Varig’s status in the Star Alliance. Would Lufthansa and Star really be prepared to ditch Varig in return for acquiring TAP?

If this analysis is correct it would leave TAP with just Iberia as an airline suitor. Local business leaders are also rumoured to be interested but whether that interest will transform into an investment is uncertain.