Continental: escaping the crisis so far

March 2003

Continental, the fifth largest US Major, has outperformed competitors on both the revenue and cost fronts over the past 18 months and, consequently, has escaped with relatively modest losses.

If the current industry environment does not worsen further, the Houston–based airline is likely to be among the first major hub–and–spoke operators to return to profitability (in 2004, at the earliest).

However, Continental has relatively weak cash reserves (only $1.1bn projected for the end of March) and limited financial flexibility (no credit line and no unencumbered aircraft).

This puts it in a vulnerable position if industry conditions deteriorate.

In other words, Continental has the potential to be a real winner — if the industry crisis does not worsen — or among the first to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy if there is a war with Iraq.

So far, the company has not been singled out for negative speculation (AMR has been the target in recent weeks). This is partly because there are no significant near–term debt maturities but also because Continental possesses special attributes that make it a textbook model of a survivor. It has relatively low unit costs, good labour relations, a flexible workforce, a balanced route system, great hubs, an acclaimed management team and promising alliance prospects.

In the short term, the key question is whether Continental will continue to find imaginative ways to raise liquidity. In December it managed to borrow $200m using spare parts as collateral, and the top management recently indicated that "other opportunities" were being pursued.

In the longer term, the key challenges will include coping with a heavy debt and lease burden, maintaining a labour cost and productivity advantage in the face of competitors potentially closing the gap, and successfully developing the three–way alliance with Northwest and Delta.

Outperforming the industry

Continental is probably the biggest 1990’s success story among the major carriers. After emerging from its second Chapter 11 visit in April 1993, the company staged an impressive financial turnaround. In the latter half of the decade, it consistently achieved high profit margins, despite rapid international growth and a process of bringing wages to industry standards.

Much of it was the result of a turnaround strategy put in place by a new leadership team, headed by Gordon Bethune, the current chairman and CEO. Also, the airline was fortunate in having "underdeveloped" hubs (Houston, Newark and Cleveland), with spare capacity and a large potential local traffic base.

The mid–1990s restructuring involved scrapping Lite (the low–cost airline venture launched in 1993), phasing out the 21–strong A300 fleet, eliminating 4,000 jobs, strengthening hub operations, bringing back first class, improving on–time performance and renegotiating debt, aircraft deliveries and leases.

Significantly, in the highly profitable late 1990s, when many other US airlines became lax about costs and saw labour expenses soar, Continental carried on with the cost cutting. When one target was exceeded, the goal was simply raised.

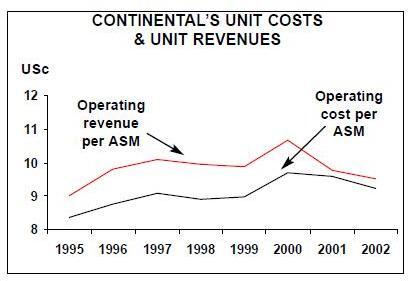

This, together with the benefits derived from fleet renewal, higher aircraft utilisation, productivity improvements and lower distribution costs, enabled unit costs to be kept in check despite considerable wage pressure.

After surging in 1996 in the wake of Lite’s disappearance, Continental’s unit revenues remained stable (around 10 cents per ASM) in the late 1990s and rose to 10.67 cents in 2000. The trend was due to a steady rise in the business passenger content of total traffic (reflecting consistently high operational performance and good employee morale), which compensated for the adverse effects of rapid expansion.

All of this meant that Continental was in pretty good shape when it entered recession and the post–September 2001 industry crisis — contrast that with the situations at United and US Airways (whose problems began long before 2001).

The Houston–based airline had also wound down the earlier growth phase in 2000.

In the past two years, Continental has posted the best operating and net margins among the large hub–and–spoke carriers. Its 2001 net loss was only $95m, or $266m excluding special items. Last year’s net loss was $451m, though the exclusion of fleet impairment and other special charges reduced it to $290m — the second–best result among the majors (after Southwest) on a "per ASM" basis.

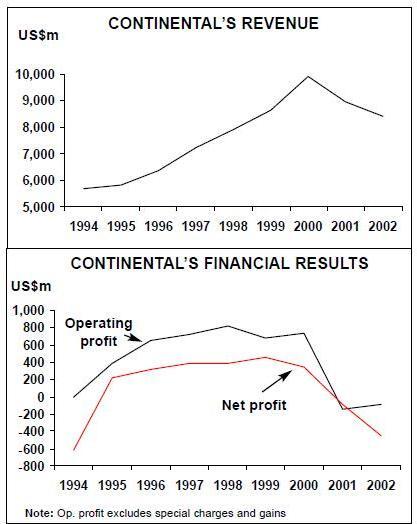

Continental has experienced just as severe revenue pressures as its competitors have in the past 18 months, as indicated by the 15% fall in its revenues between 2000 and 2002. But it has avoided the worst effects of the crisis thanks to successful capacity management and cost controls.

As an indication of good capacity management, last year Continental achieved the industry’s highest domestic load factor (73.8%) and the second–highest system load factor (74.1%, after Northwest’s 77.1%).

This was despite the fact that its 5.2% capacity reduction was less than the 7–10% contraction seen at the three largest majors.

Continental also claims to have achieved a significant length–of–haul adjusted unit revenue (RASM) premium over competitors last year, possibly because of its continued superior operational performance. Its calculations suggest that the adjusted RASM was about 10% higher than the industry average.

Of course, Continental’s actual RASM has fallen by 11% in the past two years, from 10.67 to 9.52 cents.

The airline managed to reduce its unit costs (CASM) from 9.68 cents in 2000 to 9.22 cents last year, indicating that it has maintained a cost advantage over other large hub–and–spoke carriers.

Like many of its competitors, Continental has exceeded its earlier cost performance targets. In the fourth quarter of 2002, it reduced its mainline ex–fuel CASM by 6.6%, rather than by 4–5% as planned. The various cost and revenue initiatives under way boosted last year’s pre–tax results by $130m, compared to the initial target $80m, and are now expected to contribute at least $400m to the bottom line this year.

The impressive fourth–quarter CASMreduction was driven by a new package of small belt–tightening initiatives implemented last autumn, including charging additional fees for paper tickets, eliminating certain discounted fares, rigidly enforcing fare rules and the collection of excess baggage and change fees, and modifying certain employee programmes.

A further 4% domestic capacity reduction this year (on top of last year’s 6.5% cut), to be achieved by retiring an additional 11 MD- 80s, will contribute to the cost savings.

However, at this stage Continental is still hoping to avoid additional furloughs.

The company expects another significant loss in 2003. Under a best–case scenario, it could return to marginal profitability in 2004, but there are obviously significant near–term challenges.

Now that the prospect of a war with Iraq is dragging on into the spring, it is a point of concern that Continental has no fuel hedges in place beyond the first quarter. That is in contrast to its 95% hedge position; with petroleum call options averaging $33 per barrel, for January–March.

One worst–case scenario is that a war with Iraq — and hence the temporary period of extremely high fuel prices — might spill into April and that Continental, with its already weak liquidity, would quickly run out of cash (even before the government released any assistance to prevent multiple bankruptcies).

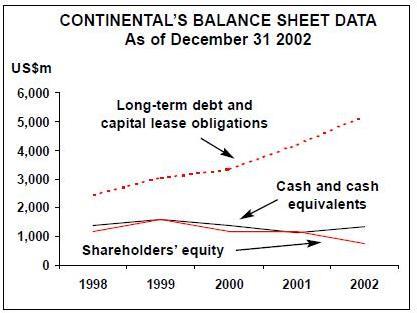

Weak liquidity, soaring debt Continental had $1.34bn in cash and short–term investments at year–end, which included $62m of restricted cash and $121m of cash held by ExpressJet. This was well above the company’s earlier $1bn target thanks to the $200m debt offering in December.

Cash burn in the current quarter has been similar to the December quarter’s $1.5m a day on an "all–in" basis (including debt payments and capital expenditures).

There has been no cash–raising, so the cash balance is forecast to amount to $1.1bn at the end of March.

On the negative side, Continental has no bank credit line (part of its financial policy — the airline’s top finance executives believe that credit facilities are not there when one needs them the most). Nor does it have any unencumbered aircraft or Section 1110–eligible spare parts.

The company still holds a 53% stake or 34m shares in ExpressJet, which it is committed to selling. The stake represents a good potential source of liquidity, but Continental would be loath to sell it until it can get a decent valuation in better market conditions. In the meantime, ExpressJet has continued to contribute nicely to Continental’s bottom line; it posted a net profit of $84.3m for 2002.

On the positive side, Continental has very modest capital spending requirements and no significant debt payments on the horizon. This year’s debt maturities are $468m. Some debt covenant issues may arise in July, but the worst–case scenario would be to have to pay off about $158m of debt.

Pension under–funding is less of an issue for Continental than for many other US major carriers, because its pension plan is smaller. Last year it also (wisely) used $150m of the ExpressJet IPO proceeds to boost the plan.

At the end of 2002 it had a total pension liability of $1.1bn. This year’s pension expense is estimated to be $325m and the cash contribution only $200m.

Even if there is a cash crunch due to continuation of high fuel prices, Continental may find novel ways to raise funds; after all, it has been extremely successful in the debt and equity markets in the past. When the times were good, the airline always completed the lowest–cost aircraft financings in the industry.

In the tough climate of the past 18 months, it has deployed a variety of cash–raising methods. Post–September 2001 transactions have included a $172m secondary share offering, a $200m convertible note offering, public and private offerings of $475m of EETCs, the ExpressJet $447m IPO, and the $200m spare parts debt offering.

If Continental makes it through the next few months, the longer–term challenge will be to repair a balance sheet that has been considerably weakened by the cash drain and increased borrowing. Total debt and capital leases amounted to a substantial $5.7bn at the end of 2002, up 25% from the year–earlier $4.55bn.

Fleet plans

As part of the post–September 2001 restructuring, Continental deferred 28 of the 48 Boeing aircraft that were previously slated for delivery in 2002. The deferrals gave Continental a 16–17 month break from new deliveries. Continental plans to take the first four deferred aircraft (all 737–800s) as early as the fourth quarter of this year, while American, Delta and others have deferred deliveries right through 2004.

Continental points out that retirements and lease expirations will more than offset the new deliveries. Under the current plan, the mainline fleet is expected to shrink from 366 aircraft at year–end 2002 to 357 at the end of 2003.

The airline is rationalising and modernising its fleet, which in 1998 included nine different aircraft types. After the grounding of the 25–strong DC–10–30 fleet in late 2001 (and the subsequent decision to permanently retire those aircraft), the number of types was reduced to five. It will go down to four when the 737–800s will have replaced the MD–80s over the next couple of years.

Continental listed 82 grounded aircraft at year–end, of which 30 were owned and 52 were leased. The owned aircraft are being carried at an aggregate fair market value of $68m. The eight owned ATR–42s have been sold, and the airline continues to explore sublease or sale opportunities for the other aircraft that do not have near–term lease expirations.

The total firm orderbook at year–end stood at 67 Boeing aircraft, valued at $2.5bn and all due for delivery by the end of 2008. ExpressJet had firm orders for 86 ERJs, valued at $1.7bn, of which 36 will arrive this year.

Labour productivity advantage

Continental’s biggest competitive advantage is its high labour productivity — one of the achievements of the early 1990’s Chapter 11 visit. For example, its flight and ground crews work longer hours, take fewer vacation days and have more flexible job duties than their counterparts at other major network carriers. The productivity advantages have been maintained while the workers' wages have been restored to industry standards.

The differentials between Continental and the least productive carriers are so large that it seems unlikely that carriers like American and United can rewrite their labour contracts to fully close the gap.

Continental is in talks with its own pilots on a contract that became amendable in October 2002, but not much progress is expected until the scope of the change is known at United and American. Its mechanics recently ratified a new four–year contract that grants them competitive wages and benefits, while maintaining the company’s labour productivity advantage. Interestingly, the deal recognises current industry conditions in that, while establishing work rules and other contract items through 2006, it includes a provision to reopen negotiations about wages, pensions and health insurance benefits in January 2004.

Alliance plans

The addition of Delta to the Northwest- Continental code–share and marketing alliance will give Continental further opportunity to strengthen its domestic market position.

The three–way deal was first proposed last summer and is now being rapidly implemented, with FFP and lounge cooperation introduced in the current quarter and code–sharing following this spring and summer.

Quantifying the financial benefits of alliance is always a nebulous exercise. Nevertheless, Continental predicts that the addition of Delta will improve its pre–tax results by $50–75m annually, after taking into account the estimated impact of the United- US Airways alliance. This would be on top of the $200m of annual benefits it claims that it already derives from the Northwest alliance.

The venture had an uncertain start in January, because the airlines chose to proceed without addressing the competitive concerns of the DoT (after the DoJ did not object on antitrust grounds). However, by March 3 the airlines had resubmitted their application, accepting three of the DoT’s six conditions and proposing amendments that would address the other concerns.

Resolving the regulatory issues will obviously enhance the alliance’s longer–term prospects.

| Orders | ||

| operation | (Options) | |

| 777-200ER | 18 | (3) |

| 767-400ER | 16 | 0 |

| 767-200ER | 10 | (2) |

| 757-300 | 4 | 11 (11) |

| 757-200 | 41 | 0 |

| 737-900 | 12 | 3 (12) |

| 737-800 | 77 | 38 (35) |

| 737-700 | 36 | 15 (24) |

| 737-500 | 65 | 0 |

| 737-300 | 58 | 0 |

| MD-80 | 29 | 0 |

| Total Mainline | 366 | 67 (87) |

| ERJ-145XR | 18 | 86 (100) |

| ERJ-145 | 140 | 0 |

| ERJ-135 | 30 | 0 |

| Total RJs | ||

| (ExpressJet) | 188 | 86 (100) |

| Out of service | Owned | Leased |

| DC-10-30 | 4 | 7 |

| MD-80 | 8 | 8 |

| 737-300 | 0 | 5 |

| 747-200 | 2 | 0 |

| EMB-120 | 8 | 10 |

| ATR-42-320 | 8 | 22 |

| Total Out of | ||

| Service | 30 | 52 |