American and United: are the turnaround plans viable?

March 2003

Senior management at American and United presented turnaround business plans to employee groups in February, including requests for immediate labour cuts of at least $2bn a year at each carrier. The need for major labour cost relief, and the risk of bankruptcy and insolvency is accepted by the key employee unions.

Regardless of the causes of the financial crisis or future industry prospects, the short term profit and cash flow gaps can only be bridged by reductions in variable input costs, and the gaps cannot be closed without major cuts in wages, benefits and staffing.

It is also widely accepted that above average labour costs is the largest of the many problems facing the troubled carriers.

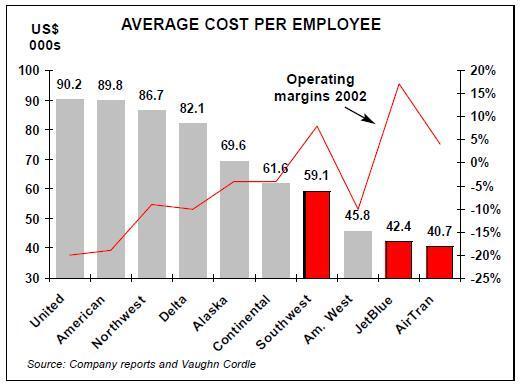

Vaughn Cordle, who has been analysing the crisis over the past two years, prepared the graph (page 3), showing the near–perfect negative correlation between average employee costs and operating profitability among the traditional Big Hub carriers.

United and American both have the highest labour costs ($90,000 per person) and the worst financial performance (negative 20% margins). If all of the Big Hub carriers had the $60,000 average employee costs of Continental or Southwest, the industry as a whole would have made a small profit last year (except for non–recurring costs), despite the adverse demand conditions.

United’s analysis suggests that roughly 30% of the labour cost problem is due to inefficient work–rules that inflate staffing requirements, 20% is related to pension and benefit costs, and half is wage related.

Lacking normal access to capital markets, the two parties most responsible for the current mess — management and labour — must reach a common agreement before the cash runs out. Management’s objective is to reduce labour costs to market levels, the most critical step to an eventual reorganisation and profit recovery, but must convince its employees and unions to accept its specific proposals. Employees and their unions will take the position of prospective investors deciding whether to "invest" these billions in the hope that management’s proposals can restore sustainable profits across future business cycles.

The employee/investors will ask the same questions that any strategic investor or outside observer would consider:

- Have the causes of the current crisis been fully addressed?

- Will the proposals really drive a long–term profit turnaround?

- What are the major business risks and the sensitivity of key assumptions?

- How will the overall risks and returns be shared?

While a failure to invest could doom these airlines, employees will be reluctant to contribute the billions they are being asked to "invest" unless they are confident that the plan will actually save their companies and provides the maximum possible protection for the returns (jobs and earnings) they are looking for. Employees and their unions will be acutely aware that the major concessions granted at several airlines during the financial crisis of the early 90s did not lead to sustainable improvements in either full–cycle financial returns or the process of distributing those returns between stakeholders.

At one level, the two plans are strikingly different (see boxes on pages 4 and 5 for details). United argues that fundamental changes in corporate structure and collective bargaining arrangements are needed in order to drive a major cultural "transformation", while American’s plan stays strictly within current structures. At another level, the proposed changes to cost structures and network operations (that would be visible to customers) are virtually identical. United’s pilot union has already signalled that it is fundamentally dissatisfied with both the business logic and the investment risk of management’s plan, and may attempt to propose an alternative plan.

Strict focus on cost reduction

Employees hoping that management would put forward a comprehensive explanation of how competitive forces have altered the prospects for future earnings (and thus sustainable cost levels), and their plans of how to maximise future earnings given these changes, will be badly disappointed.

Aside from noting the growth of Southwest and other LCCs, and that operating costs are well above current revenue levels, neither presentation attempts to explain the root causes of the crisis or demonstrate an overall approach to solving those issues. The analysis presented is static. Here is today’s gap between costs and revenue, and here are the cuts that would close that gap.

Cost reduction is the only action proposed by management.

United proposes a two–tier cost reduction, with more draconian cuts for employees operating flights directly competitive with LCCs. Although huge marketplace shifts have occurred in the last five years, neither presentation mentions the possibility of further changes, or whether the proposed cost cuts will be adequate if negative trends continue.

At United, the crew on the flight from O'Hare to Baltimore would simply be paid 25% less than the crews flying from O'Hare to LaGuardia, while American’s proposed cost cuts would be spread more evenly and would not be route–specific.

No attempt is made to distinguish between cost cuts needed to address cyclical issues versus structural or permanent declines in competitiveness. United notes labour’s wildly disproportionate current share of economic value, given the wage increases granted at the peak of the dotcom bubble, but the unions might not readily accept new levels based on an extreme down–cycle. The broader (but more complex) question of how labour compensation should be structured vis–à-vis other stakeholders over a full business cycle is not addressed.

Understandably, neither carrier attempts to forecast the specific risks of an Iraq war, but they do not even attempt to explain the link between GDP forecasts and profit recovery or how future revenue projections reflect the permanent changes in the pricing environment.

Neither plan mentions the impact of the massive dotcom over–expansion on pricing nor whether supply/demand or pricing conditions are likely to change. Both carriers assume its current network size and shape is optimal, or would become optimal with lower costs. Although Southwest has steadily taken share from the Big Hub carriers, and maintains a huge cost advantage, the magnitude of further share losses is not estimated.

There is no discussion of the type or scope of markets where United and American might have sustainable advantage versus the markets where Southwest has a clear advantage, nor of any factors that might affect relative advantage other than cost.

United explicitly argues that it "must respond to the LCC threat" and that Starfish is required for this purpose. American says it wants to retain its Hub focus and limit direct LCC competition. In practice, both carriers plan to continue to operate today’s route network with relatively minor changes.

The extreme emphasis on cost reduction is appropriate in the short–run as management has no other meaningful way to leverage this year’s financial performance. But the static approach to target setting, and the failure to put this cost reduction in any broader strategic context may give the employee/investors cause for concern.

Many employees have already voiced concerns that the current concessions will prove inadequate and management will need to return with further demands. While future profitability could be affected by changes to aggregate capacity, pricing, market and competitive focus, both airlines have proposed plans strictly limited to major reductions of costs to market levels, without explaining why that would be the best approach and why other elements of strategy did not need major adjustment in light of market changes.

Future revenue premiums?

Both the American and United employee presentations point to historical unit revenue premiums and both plans assume that those premiums are structural and will continue. American’s assumed 30% unit revenue premium is the starting point of its entire request for labour concessions. Although this may not be intuitive to front–line staff, no effort is made to explain the assumption or why it would be sustainable as the industry undergoes major changes. Management thinking appears virtually the same: American says the premium comes from "loyalty and brand strength", United says the premium is due to the value of their "brand, schedule, frequent flyer program and product".

Both American and United are saying, that "given an equivalent choice, people will pay more money to fly with us".

Customers like the brand, think the product is superior, and proactively demonstrate loyalty.

In reality, most of the observed revenue premium comes from operating in markets with less price competition. In many cases, the higher prices are sustainable as the markets have inherently higher costs.

New entrants have little prospect of achieving lower costs on low demand domestic O&Ds, long–haul international markets or the full range of O&Ds served from dominant hubs such as Minneapolis or Atlanta. Some of the premium comes from niche products such as First Class, and from Big Hub pricing and yield management approaches that more aggressively prices peak capacity and more aggressively discounts off–peak seats.

Southwest currently never charges more than $158 St Louis — Baltimore, even the day before Thanksgiving, but American will charge a lot more when demand outstrips supply.

Big Hub carriers will continue to observe higher unit revenues than Southwest, but on a diminished basis as LCCs expand and pricing structures are simplified. But it will not come from customers loyally choosing United/American over Brand X. AAdvantage loyalists may have routinely called American without price shopping in the days when industry price differences were much, much narrower and the chance of finding a price/schedule alternative that offered clearly better value was much, much lower. Those days are long gone.

Bubble era $1,000 business fares destroyed any sense of customer value (much less loyalty), and people are now well trained to search for alternatives.

But you would not guess that from the American or United presentations, which treat revenue and competition in wholly static terms, relying on assumptions developed when LCCs were less than 2% of the industry.

Customers will continue to value the strong Big Hub networks, but revenue forecasts cannot assume any significant customer value beyond the basic schedule.

Higher unit revenue results from a combination of competitive conditions and the willingness of customers to pay more for a service they value (much more service than Cincinnati or Fargo could support under the Southwest business model, greater last minute seat availability on Friday evenings).

These more aggressive revenue assumptions might give investors reason to doubt that management has fully appreciated the major competitive and pricing changes of recent years. Another danger is that when management implies that people deliberately pay more to fly on American or United, it may reinforce the sense of entitlement traditionally used to justify above–market labour compensation.

United's new airline-within-an-airline

United’s unions have announced their opposition to Starfish, which would operate 35% of the domestic narrowbody fleet. Starfish is intended to give United two different cost platforms, and would presumably be the platform for future growth.

Starfish would be a new start–up airline, with separate operating licenses, management, union contracts and seniority lists.

United argues that full segregation of operations and collective bargaining terms is necessary to make a clean break with the labour–management attitudes of the past and to prevent Starfish practices and cost levels from rapidly reverting to the higher United Mainline levels. While conceding the seriousness of the cost problem, the unions object strenuously to the breakup of the current United seniority system, and are concerned that management would continue to move aircraft and staff out of Mainline.

The unions have also objected to Starfish as unworkable from a business perspective. The task of starting up an airline with 134 aircraft, with all of the attendant hiring, transfers, training and logistical work would be daunting under the best of circumstances. It would burn cash at a time of critical liquidity.

Starfish staff would be asked to adapt to a totally new style of operations immediately following huge pay cuts and career disruption. The unions do not believe that Unitedmanagement is up to the task of managing this totally new operating approach, noting that it must simultaneously manage the financial reorganisation, and massive layoffs and changes in every other part of the company.

United’s entire plan is based on the need to counter attack the LCCs, who have undermined their traditional core business revenue base, while expanding leisure demand, where United is uncompetitive. United’s plan rejects the approach used by both traditional airlines and LCCs who attempt to serve a broad range of business and leisure demand on every route. It believes that customers on some (Mainline) routes primarily value "recognition and improved process" while customers on other (Starfish) routes focus on "value for money".

Once again this suggests that United thinks there are customers who not only prefer United to Brand X, but are not highly focused on "value for money" and are content paying higher fares for normal economy service. United proposes operating Mainline "business" routes such as Chicago- LaGuardia with two–class aircraft and tight connections while Starfish "leisure" routes such as Chicago–Baltimore would use high density aircraft that would be scheduled for maximum utilisation, not connections. United’s plan not only rejects its longstanding approach which maximises network utility and scope at its hubs, but also rejects key features of the Southwest approach to operations which maximises product standardisation and simplification and totally avoids operational complexity such as connections to a wide range of international, regional and interline flights.

United acknowledges that every previous "airline–within–an–airline" attempt has failed, but fails to provide employee/investors with a clear explanation of why this attempt might succeed. The more rigid segregation of operations and union contracts may prevent backsliding, but will also impose huge start–up and overhead penalties. A more gradual approach would reduce short–term savings and preclude the cultural "transformation" that United says is critical. United notes that other recent variations on this strategy (Zip, GermanWings, Song) have market focus and branding totally distinct from their parent, but Starfish will be tightly integrated into United’s hubs and brands.

Lessons from Southwest

United explicitly acknowledges that no US carrier other than Southwest has provided strong, steady financial returns to all stakeholder groups, and that only Southwest has a robust business model incorporating best–in–class costs, clear value propositions for both customers and employees and disciplined growth in target markets.

But instead of Southwest’s disciplined focus on a target market where it has sustainable competitive advantage, United still seems attached to the thinking of ten years ago, and wants to be all things for all customers, with a product for every segment. It is unclear how United’s plan would create new value for any customer segment, critical issues such as pricing are not mentioned, and traditional network strengths might actually be reduced. There is no attempt to demonstrate competitive strengths that could earn returns over a full business cycle. Instead, the plan appears motivated by the loss of market share to LCCs and focuses narrowly on this year’s gap between revenue and costs.

While United’s presentation devotes thirty slides to the need to provide a strong value proposition for employees, and to tightly align staff motivation and corporate strategy, it ignores the practical problems of achieving this while also laying off tens of thousands of staff, gutting past collective bargaining agreements and pension plans and facing a serious threat of liquidation.

American’s plan retains its traditional Hub based strategy, which is widely understood and accepted by staff, but offers no guidance as to how that strategy can be improved or sustained in the coming years.

While United’s plan for countering LCC growth is unconvincing, American simply does not address the question of whether it can compete successfully at either its current size, or some smaller size. It would be quite fair to argue that the need to rapidly implement major cost reductions outweighs the need to calibrate longer–term strategies, but management has offered these as structural solutions. The employee/investors are openly concerned that they have been asked to contribute billions towards what is only an interim first step.

The labour dilemma

Neither airline has hope of attracting critical outside investment without bringing labour costs in line with market rates.

If the unions were to agree to the cuts management has requested, existing creditors would have a much greater chance of full repayment and new investors would have the prospect of reasonable returns.

But it is unclear why the employees would agree to totally gut their collective bargaining agreements and pension plans and end the careers of perhaps 30% of their colleagues and then allow all of the future benefits to go to outside investors.

Neither plan mentions any future compensation or upside benefits should the employee investments succeed in restoring the airlines' financial health. American acknowledges that it is open to negotiation on any approach that would provide the needed savings, but also explicitly states that preservation of the current ownership and capital structure is a major objective.

United’s unions have a more difficult decision as there is no recapitalisation plan so they are being asked to contribute billions without any way of knowing who will control the company in the future.

None of the available alternatives at this point offer huge cause for optimism. Employees may accept especially painful cuts if management makes a powerful case clearly based on the changes in the marketplace, proposes a convincing new business model that responds to those changes, demonstrates that it has made a major break with the failed approaches of the last five years, and was serious about achieving a Southwest–type solution where all major financial stakeholders could earn reasonable, reliable returns over the full business cycle.

However it is yet to be proven that the unions will freely agree to the magnitude of cuts needed to drive a full profit recovery, even under the pressure of the bankruptcy process. Management could attempt to permanently break the unions, and this would certainly facilitate new outside investment, but might undermine already fragile service and productivity levels.