New Air Canada: its real prospects

March 2001

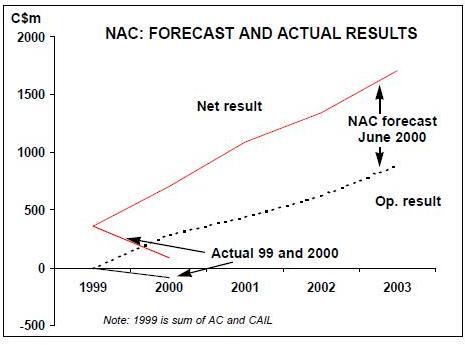

Last summer the management of Air Canada assured stock–market analysts that the merged Air Canada /Canadian, with its near–monopoly domestically, would rapidly produce positive financial results. In the event the net result for 2000 was a loss of C$82m against a forecast profit of C$286m. What’s gone wrong, and what are the real prospects for New Air Canada (NAC)?

In reality, the Air Canada / Canadian integration was going to be tough even in positive market conditions. Rationalising heavy route system overlaps while merging the remnants of the eight airline cultures that go to make up NAC was an enormous challenge, which should have been a red flag even to the most bullish. The re–alignment of Toronto operations (Terminals 1, 2 and 3) proved not only complicated but expensive. Serious customer dissatisfaction remains, which existing competitors and ever multiplying new entrants are hoping to leverage to their advantage. Also,the loss of oneworld feed to/from Canadian has diluted the value of that carrier to NAC.

Since the mid-'90s Air Canada had out–competed Canadian on newly liberalised Canada–US route sectors. Now the NAC faces a situation where US domestic growth is slowing while competitive intensity increases, with many US carriers rapidly adding RJs to their US–Canada operations. The United/US Airways deal, if it goes ahead, will cause a Star problem for NAC, as United will want to leverage the extensive transborder network it would gain from US Airways.

An alternative perspective

Meanwhile, NAC has begun cutting capacity, frequencies, routes and people. It has announced 3,500 voluntary layoffs but it now seems that about 10,000 total cuts will be necessary. Internally, union seniority arbitration will be difficult, especially in an environment of looming cutbacks. NAC is also being hit by the same things plaguing other carriers — fuel costs, slower than hoped Asian market recovery and a decline in US economic growth so steep even the US Fed seems to have been caught off guard. NAC management still seems intent on its strategic business unit (SBU) approach that will break–up the company into smaller more manageable chunks. So far limited tangible action has taken place on the SBU thrust, and the incremental costs of infrastructure duplication remain a real concern. Nevertheless, the standard political view of NAC is that it has been allowed to gain a monopoly situation in the Canadian market, and the integration costs are essentially teething problems. There is a pressing need therefore to protect the smaller Canadian airlines through the Commissioner of Competition’s special powers in the aviation sector — described in the following article.

An alternative perspective is that NAC is far from being in a potentially strong position; indeed, the political complications resulting from the take–over of Canadian may mean that NAC will find itself where Canadian was 12 months after its own acquisition of Ward Air (1991) — short of cash, in a recession, and saddled with a non–competitive cost profile.

Back in 1999 the government (both federal and some provincial) finally decided that it was unwilling to bail out Canadian again. Instead, it opted for a radical policy rethink, abandoning the key concept of maintaining a lopsided duopoly. By providing antitrust exemptions for merger talks and questioning the protective covenants on shareholder control contained in the Air Canada Privatization Act, the government signaled its willingness for others to bid for both Canadian and Air Canada. In the fall of 1999 air traffic growth was still strong and it seemed that nothing but synergies would emerge from some form of a merger or forced amalgamation of Air Canada and Canadian. Importantly, the government would be spared the embarrassment of mass redundancies should Canadian go out of business.

Onex Corp., backed by American Airlines and politically well–connected, could have provided the ideal suitor for both airlines, as well as alleviating some political difficulties.

Government could always claim that a market solution had prevailed over the traditional political subsidy alternative. A new crop of vigorous new entrants would, in the fullness of time, be counted upon to provide the newly merged beast with customer pleasing competition. Airline customers (voters) would see that this was the right solution and government would be happy to provide those competitive safeguards that would make the whole restructuring work.

However, Air Canada, backed by its Star partner Lufthansa, launched its own successful bid to take over Canadian, adding debt and a very weak operating brand to its own ineffective cost structure. Had Canadian been allowed to fail, which it was close to doing in late fall of 99, Air Canada would have been a strong contender for the few valuable Canadian assets remaining.

Canadian’s political legacy

But, distracted by the heat of the Onex battle, Air Canada was not only forced to buy all of Canadian but also to agree to a series of social commitments with the government.

These undertakings sought to calm both public and employee fears over massive lay–offs, abandonment of thinner domestic route, unbridled price rises, etc. Meanwhile, the government increasingly presented itself as a white knight who would ensure the new Air Canada would honour its commitments to employees and the public.

By winter 2000 the problems of merging Air Canada and Canadian were causing an uproar thereby fortifying the government’s role in defending the monopolisticallyimpaired traveller. The summer of 2000 is remembered as one of the worst in terms of service quality that Canadian air travellers have ever seen. The government now decided to create an airline complaints ombudsman post, appointing a former National Hockey League referee as its first office holder.

In late 2000 NAC decided to respond to new entrant Canjet by using the usual tools. Canjet complained and the government decided to restrict NAC from playing with fares or capacity too much lest they be considered predatory. So the deregulated market is now somewhat re–regulated, with a policy objective of increasing competition — a re–balancing of Canadian domestic market share to about 60% for NAC and 40% for the rest.

What gives?

Finding itself in this situation, NAC, the highest cost player in the market, has to cut routes, jobs and airplanes, but its ability to do so is curtailed by its public commitments to government. Thus voluntary job cuts and route capacity contractions, mostly internationally, are all NAC is allowed to do to get to a recession–survivable position. Soon something will have to give. Most likely will be a re–negotiation of some of those government commitments. Otherwise NAC will spill copious incremental amounts of red ink. In fact, in 12 months from now if no major internal synergies (C$700m was initially mentioned by NAC management), are allowed,and markets continue to slow, and competition continues to escalate, and fuel continued to rise, and Canadian debt continues to weigh heavily on NAC, then things look decidedly bleak. At that point NAC will be where Canadian was by mid- 1999 except this time there will be no other major Canadian carrier to merge or absorb NAC. So what then?

Some interesting options present themselves. By the fall of 2002 NAC will have the justification to do all the cost–cutting and structural synergising it can muster. Other lower cost domestic market carriers (WestJet, Canjet, Canada 3000, etc.) will have grown, and could conceivably have garnered 30%-plus of domestic point–to point traffic, thus making things seem less monopolistic.

With markets either at or close to their cyclical low it is not a major leap to posit that NAC financials would be precarious by the end of 2002. NAC’s need for further debt support or cash infusion could then possibly put the carrier in play once again.

Enter the government, which would presumably be searching for another market solution, so avoiding unnecessary government fiscal involvement. And the startling opportunity to repeat the events of the fall of 1999 emerges.

Onex or some other Canadian venture capital firm could step forward with the assurance of either formal or tacit government approval. To the acquirer the transaction would seem much easier to accomplish than the original Canadian buyout by Air Canada.

By fall 2002, domestic monopoly is no longer a hot potato, much of NAC’s cost re–alignment is done, markets are flat or turning up, customers’ memories of the terrible summer of 2000 are fading, and union integration issues are at least partly resolved.

If anything resembling this scenario were to materialise, then NAC shareholders would consider the merger a failure, but Onex or another VC firm might consider the longer term result a success. Time will tell as it always does.