Japanese deregulation: Skymark and Air Do jolt JAL, ANA and JAS

March 1999

This year will see the curtain of deregulation finally rise on the domestic air transportation industry in Japan. 1998 saw the dramatic debut — at least in Japanese terms — of two new airlines, Skymark Airlines and Air Do. Skymark started operations on Haneda (Tokyo) to Fukuoka — the second busiest domestic route — on September 19, while Air Do started flying between Haneda and Sapporo — the busiest domestic route — on December 20. Their impact on the domestic aviation market was instant.

That’s because Skymark and Air Do are the first new entrants in 43 years (since JDA, now known as JAS, began operations in 1945) — and thus they have an importance way beyond their current small size.

Partial deregulation was introduced in Japan in 1985 when the government abolished the so–called 45/47 policy (named after the Japanese Showa year, equivalent to 1970/71), which had applied strict economic rules to all aspects of the Japanese airline industry. The three main airlines — JAL, ANA and JAS — were required to follow the Ministry of Transport’s (MOT’s) ‘administrative guidelines’ as to their business plans and domestic and international routes flown.

The partial deregulation enabled the three carriers to make their own decisions on capacity increases, introduction of new types of fares, routes to fly, etc. In 1997, the government further deregulated the business by allowing new entrants into the domestic market.

The new carriers

Skymark Airlines was set up by HIS, which is the number two Japanese tour operator in terms of overseas travellers handled. As well as developing into the airline business via Skymark, HIS is a major force behind changing the distribution system in Japan.

Air Do started up with 26 shareholders, owners of small- and medium–sized Hokkaido–based companies, plus professional individuals. The main shareholders are now Kyoto Ceramics, Reikei Co., Tokyo Marine and Fire Insurance and Hokkaido Electric. The company has made a direct appeal to the citizens of Hokkaido to support the new airline and bring more affordable fares to the region. So far 7,000 shares have been sold at Y50,000 each ($450) mostly on a one share per person basis, which has created a useful market of loyal passengers.

From the outset, Skymark Airlines and Air Do have been achieving load factors of around 80%, compared with the initially expected level of 70%. Moreover, Skymark Airlines has introduced a second 767 from November last year and has applied to the MOT to open two new routes Osaka- Fukuoka and Osaka–Sapporo, as Tokyo (Haneda) slots are virtually full at present. Air Do also plans to introduce a second 767 this year.

Impact on the domestic market

Skymark Airlines and Air Do introduced a new concept to the Japanese domestic market — no frills service and fares 36% cheaper than the incumbent in Skymark’s case and 50% lower in Air Do’s.

Japan Airlines, All Nippon Airways and Japan Air System have been forced to react to the entry of the two new airlines. They have been expanding FFP programmes aggressively in an attempt to tie up their customers; JAL has 4.3m members, ANA 3m and JAS 1.5m. Skymark and Air Do have no plans to introduce an FFP (though Air Do has the support of the 7,000 shareholders in Hokkaido).

Moreover, the three incumbents advertised 30–40% discount fares on the routes that the new entrants were going to operate, although the fares were limited to advance purchases of restricted seats. Yet such drastic discounting efforts did not prevent the drift of passengers to the new airlines. Passengers flown by JAL and ANA between Tokyo and Fukuoka in October were down by 5.0% and 6.5% respectively. Load factors dropped by some 10 percentage points; from 75.5% to 65% on JAL and from 75% to 66.2% on ANA, as against 81.3% for Skymark.

MOT statistics for the peak peak season traffic between December 25 1998 and January 4 1999 show that total passengers carried by all the domestic carriers registered a tiny growth of 0.3% on a year–on–year basis, but that total passengers carried by JAL, ANA and JAS fell by 1.7%.

Also, passengers on the high–speed Shinkansen train operated by JR Sanyo between Osaka and Kyushu Island, where Fukuoka is the major city, decreased by 8%. JR attributes the decline to competition from the new airlines.

In the latest development, JAL, ANA and JAS have extended reduced fares (which match those of the two new airlines) onto 50% of the frequencies where Skymark and Air Do compete.

This will inevitably squeeze profitability on their two main domestic routes. ANA, for example, generates some 16% of its revenue, and a higher proportion of its operating profit, on the two routes. On Tokyo- Sapporo, JAL alone operates 11 747 flights daily plus one DC–10 flight, and ANA and JAS have similar frequencies.

As Skymark and Air Do expand with the Osaka routes, the incumbents’ control of the domestic market will be further eroded. Domestic revenue as a proportion of total revenue is 26% for JAL, 70% for ANA and 94% for JAS. Unfortunately, there appears to be little prospect that the new entrants will stimulate the overall market because of the depth and extent of Japan’s recession. Their impact is therefore directly on the three incumbents’ traffic and yields. The high–speed Shinkansen train is also going to continue to lose passengers.

Cost breakdowns for the two new airlines are not yet available, but they seem to be pursuing classic low–cost strategies. They are minimising overhead costs by outsourcing, selling a simple fare structure and reservation system, offering no frills in in–flight service, using direct sales, and avoiding FFPs.

Skymark and Air Do have also entered into an agreement to share facilities at airport offices. Skymark has a maintenance agreement with ANA, but ANA is apparently claiming that it does not have capacity to handle more than a couple of Skymark aircraft.

Meanwhile, JAL, ANA and JAS are still operating on most of the non–profitable routes, a legacy of the MOT’s administrative guidelines. And the three airlines, or at least JAL, are no longer very high cost plus high yield airlines by international standards. Air fares in Japan have fallen by 17% on domestic routes and by 29% on international routes during 1990–1997. JAL’s staff cost is coming down to Western levels with the wage bill having been cut by 41% since 1990.

Domestic yield is no longer completely out of line with the US industry. In 1997 revenue per RPM was 22.3 cents for domestic Japanese service (at US$=Yen130) which could be compared to US Airways’ average yield of 17.2 cents.

But 25% of the unit revenue goes to pay user charges in the case of Japanese airlines, while it is only 3% in the case of US airlines. A comparison of average landing charges, for example, reveals that prices at Narita, New Kansai and Tokyo–Haneda are two and a half times higher than at JFK–New York.

However, the entry of the two new airlines is helping to accelerate the reform and rationalisation of the distribution system in Japan. Publishing discounted fares is an innovation in Japan where passengers looking for reasonable fares have traditionally had to search around buckets shops in the hope of finding a tour package to fit their schedule. As already mentioned above, HIS is the leading tour operator in selling promotional tickets directly to the Japanese flying public.

The incumbents’ strategies

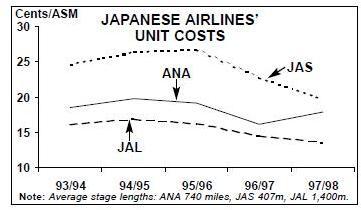

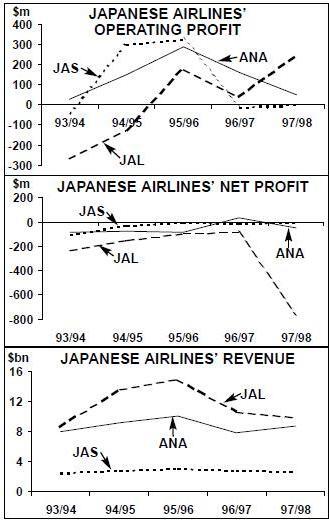

As the graph on page 15 illustrates, the three main incumbent airlines have been consistently loss–making over the past five years, and the Asian downturn is unlikely to improve matters in the 1998/99 financial year.

JAL’s 1998/99 half–year year results (the six months ending September 30 1998) included a 6.5% fall in net profits — despite a 10% fall in fuel costs. In the half–year international passengers carried rose by 1%, but this was the only good news in the face of a 0.7% fall in domestic passengers (with overall passenger load factor dropping by 1.7 percentage points) and a 3% fall in total cargo carried.

As a consequence of these results and the ongoing Asian crisis, the airline has halved its 1998/99 full–year forecasted profit to Y10bn ($85–90m).

The obvious reaction is cost–cutting, which JAL is trying to implement as much as possible. In 1997 JAL had announced a four–year medium–term restructuring plan for 1998–2001, but the worsening Asian situation forced the airline to reshuffle its medium- term plans in October 1998. The new measures included:

- Advancing the target year for a 10% cut in units costs from 2001 to 2000;

- Further reducing planned aircraft purchasing (by another 10 units) in order to improve cash flow by a predicted Y12,000m by 2001;

- Cutting staff numbers further, with 2,300 staff going by 2001 instead of 1,500 in the initial plan; and

- Putting much greater emphasis on restructuring domestic operations, increasing services on profitable routes and cutting loss–making routes. More domestic services are to be handed over to the subsidiary JAL Express.

In January 1999 JAL announced that as a corollary to domestic restructuring the airline would be expanding its international services — particularly transpacific. Codesharing ties with oneworld members will increase substantially this year, including with American in the second quarter and with British Airways and Cathay Pacific in the third quarter (although JAL may be wary of getting too close to the oneworld grouping).

ANA, on the other hand, reported a 68% increase in net profit for the first–half of 1998/99. ANA’s domestic load factor fell 1.1 percentage points while its international load factor rose 1.5 points in the half–year. Domestic cargo revenue rose 9.3% while international cargo revenue rose by 7.5%.

ANA claims that, although it faced the same domestic and international pressures as its rivals, it managed to weather the Asian storm better due to successful, continuing restructuring. On February 19 ANA announced a plan to transfer unprofitable routes to/from New Kansai and local cities — some 20% of its current 100 routes — to subsidiary Air Nippon (ANK) over the next three years. ANK has smaller aircraft types and its staff costs are some 15% lower than that of ANA.

Although conditions will remain difficult in the second–half of its fiscal year, ANA says that it is confident that its restructuring will leave the airline well–positioned once the Asian crisis improves.

Japan Air System appears to have suffered the most out of the three incumbents from the Asian downturn.

In the half–year to September 30 1998 JAS recorded a net loss of Y237m ($1.9m), compared with a profit of Y700m in April- September 1997. This result effectively means it will be very difficult for JAS to break–even this year, despite deep cost–cutting measures that have included the planned transfer of all international routes to subsidiary Harlequin Air. JAS also agreed a 3% wage cut with unions, although initially management has wanted a 10% cut in wages.

The future for ANA, JAL and JAS

Despite all the cost–cutting and restructuring, it will not be at all easy for the three incumbent airlines to make their operations profitable until the Japanese economy recovers.

Perhaps their profitability long–term depends on collaboration, rather than continuing fare wars that damage everybody. Last month (February) JAL and JAS announced plans for a CRS joint venture that will take effect from April 2001. Equity will be split 50:50, and the two airlines forecast that the CRS joint venture — which will also handle FFPs and yield management — will cut $100m from joint costs over an eight–year period.

ANA will not be part of the joint venture, stress the two other airlines, although ANA, JAL and JAS signed an unconnected agreement in November 1998 for the sharing of domestic computer infrastructure (but not content).

Inevitably perhaps, the CRS joint venture move has prompted some analysts to speculate that it may lead to further operational/ marketing tie–ups in the future, perhaps leading to an eventual merger between JAL and JAS. A merger might make strategic sense (although ANA and the two new airlines would disagree), but any such equity linkage remains — for now — a long way in the future.