AirTran: the airline formerly known as ValuJet

March 1999

AirTran Airlines has reported a profit for only one quarter in the past three years but has survived thanks to enormous cash reserves. Is it now nearing a liquidity crisis? Over the past year the low–cost carrier has gone up–market and will be the first to introduce the 717 this summer. Will its new CEO — Joseph Leonard — get the costs down and restore profitability?

AirTran has had a brief but chequered history, even by US new–entrant carrier standards. It began life as ValuJet in October 1993, offering low–fare services in competition with Delta in leisure markets out of Atlanta, and became an immediate success in the marketplace.

Its June 1994 IPO and subsequent spectacular financial success made it a favourite on Wall Street and set a favourable trend for new entrants generally. The rapidly expanding carrier earned net profit margins as high as 16–18% in 1994 and 1995, as its yields were among the best and unit costs the lowest in the US airline industry.

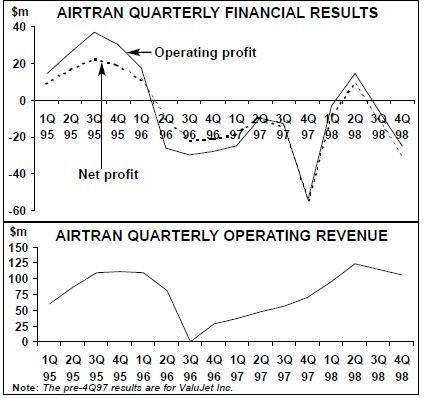

Then it all went wrong. A crash in May 1996, followed by a safety review by the FAA and a four–month grounding, changed ValuJet’s fortunes in a short period of time. However, there had already been signs that rapid growth and Delta’s more aggressive pricing would reduce ValuJet’s profit margins. The net effect was a $41.5m net loss for 1996, in contrast to the previous year’s $67.8m profit.

ValuJet was able to weather the crisis because of its exceptionally strong financial position: it had $254m in cash in April 1996. But when it was finally allowed to resume scaled–down operations at the end of September that year, it faced formidable challenges. On the revenue side, it faced a severe image problem resulting from the negative publicity and the extended debate about maintenance practices — something that affected the low–cost industry sector generally. ValuJet found that it had to discount heavily to win back passengers, which depressed yields, and even then load factors were unsatisfactory.

The problem on the cost side was twofold. First, the carrier was handicapped by a reduced fleet size (just 15 initially) and was not allowed to build up the fleet fast enough. In the summer of 1997 it was still five aircraft short of the 30 considered necessary to restore profitability.

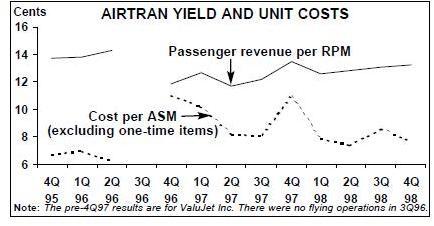

Second, increased maintenance needs and structural changes required by the FAA had an adverse impact on unit costs, which surged from under 7 cents/ASM in 1995 to 9.40 cents in 1997. To tackle the new challenges, in November 1996 ValuJet strengthened its leadership by appointing former TWA and Continental president Joseph Corr as president/COO. The two top executives and original founders of ValuJet, Robert Priddy and Lewis Jordan, focused on overseeing the operations of a newly–created holding company.

The leadership believed that the higher costs would be largely offset by efficiency improvements. But some of the cost increase was permanent, because the changes implemented in maintenance, organisational structure and compensation methods made ValuJet a more conventional type of operation. On the positive side, it passed all the subsequent FAA inspections with flying colours.

After $48m net losses in October 1996–June 1997 and when facing a further loss in the critical third quarter of 1997, the company grabbed the opportunity to buy AirTran Airways for $62m and give up the ValuJet name. The merger, completed in late 1997, retained key directors from both companies and gave Joseph Corr the job of CEO. It also spawned a new business strategy designed to attract a broader customer base.

The high costs associated with the merger, aircraft refurbishment, product rebranding and an aggressive advertising campaign contributed to the doubling of the net loss to $96.7m in 1997. But hopes were high that cost synergies would kick in and that profitability could be restored in the summer of 1998.

One of the biggest potential benefits was an immediate substantial increase in scale from 32 to 43 aircraft. ValuJet also benefited from AirTran Airways’ maintenance facility in Orlando. However, a mix of DC–9s and 737s did not make any sense.

By March last year AirTran reported that a turnaround was well under way and that it would be “solidly profitable” in 1998. A $8.6m net profit was posted for the second quarter — the first positive result in two years. But the important third quarter saw an unexpected $10.9m loss, which was blamed on predatory pricing by Delta, higher maintenance costs and expenses associated with threatened job action by flight attendants.

The latter looked like a major blunder: the company had spent $3m to reconfigure aircraft so that they could be operated with fewer crew members in the event of work stoppages by flight attendants, which seemed likely when a 30–day cooling off period expired in early September. But the threat was averted when agreement was reached on a new contract.

In an attempt to rescue the situation, a major route realignment was implemented in September that eliminated several cities from the network but boosted service in key business markets. This necessitated some furloughs, including pilots and flight attendants.

But AirTran reported a $40.8m net loss for 1998. That included a $27.5m charge to write off the 737 fleet, but the previous year’s results included a similar amount in shutdown, rebranding and other special charges. Nevertheless, the 1998 loss was less than half of the previous year’s and, when the fleet charge is excluded, AirTran was close to break–even in the fourth quarter.

The past year’s trends in operational performance have been in the right direction. Unit costs fell significantly at long last, from 9.40 cents per ASM in 1997 to 7.90 cents in 1998 (excluding onetime charges), helped by a 16.4% decline in fuel prices. Traffic and revenues more than doubled, while the load factor rose by 6.7 points to 59.6%. Yield and unit revenues rose by 3% and 15% respectively in 1998, though the average fare and yield trends reversed in the fourth quarter when AirTran faced the same considerable pressures on the pricing front as the rest of the industry.

A turnaround is all the more critical because AirTran’s previously substantial cash reserves have whittled down to almost nothing. The reserves have fallen at a steady rate from $254m in April 1996 to just $43m at the end of September 1998. On the basis of the fourthquarter loss, the year–end cash figure (not released) could be as low as $10m.

On the positive side, the company has kept its debt burden moderate by selling surplus DC–9s (which were kept in pristine condition during and after the 1996 grounding by sending them to the Mojave Desert) and refinancing or retiring debt, which has helped offset initial payments for the 717s. But the continued losses and uncertainties have had an adverse impact on credit ratings.

AirTran’s share price fell from a peak of $25- $30 in early 1996 to less than $5 at the end of that year and has since then barely risen above that level. In mid–February the price was just over $3.

New leadership

The failure to return to profitability, as well as debacles like the spending on possible job action by flight attendants, cost CEO Joseph Corr his job — he resigned in January. The company said that Corr, a turnaround specialist, had been taken on the understanding that he would only lead the air–line through the restructuring process, but he would have obviously preferred to see profits. AirTran named a prominent AlliedSignal executive, Joseph Leonard, as chairman, president and CEO.

Leonard, a 30–year airline industry veteran with stints at Northwest, Eastern and American, is extremely highly regarded in the industry. He has been described as a strong and aggressive leader, with a record of improving profitability. He has been given a clear line of authority in his new position, which many think bodes well for AirTran.

Leonard has indicated that, in addition to continuing Corr’s focus on safety, reliability, caring customer service and market image as a value producer, his immediate focus will be on the basics: reducing AirTran’s unit costs to around 7.50 cents per ASM and improving liquidity.

Fleet plans

Fleet strategy plays a critical role in AirTran’s cost–reduction and financial recovery efforts. First, there is the ongoing process of simplifying the existing fleet. Second, the 717 will offer substantial cost savings — the airline says that it will be 20% cheaper to operate than the DC–9–30 and up to 35% cheaper at peak periods.

Having earlier standardised the DC–9 fleet from as many as 11 different configurations to just one and disposed of the MD–80s, AirTran has now accelerated the retirement of the 10 737–200s gained in the merger. Five will leave the fleet in the second half of this year, and the remaining five (of which four are owned) are expected to retire early next year. The 40–strong DC–9–30 fleet will remain unchanged in the short–term.

Both the DC–9 and the 737 will be replaced by the 100–seat 717–200 — the former MD–95 ordered by ValuJet. There are 50 firm orders and 50 options, with deliveries beginning this summer. In addition to securing good prices, AirTran’s launch customer status has given it useful publicity — the aircraft rolled out in its colours in late January.

The speedy 737 retirements mean that there will be no net addition to the fleet this year. From next year, the plan has been to retire one aircraft for every two 717s delivered. However, fleet growth may well be slowed by liquidity considerations or a desire to halt growth temporarily in order to restore profitability.

Route network strategy

AirTran has returned to most of the old ValuJet markets. Its network now covers 29 cities throughout the Southeast, Florida and the East coast, including many in the Northeast and Midwest. The hubs are at Atlanta and Washington Dulles. The merger meant a relocation of headquarters from Atlanta to Orlando — apparently due to incentives provided by the state of Florida.

But AirTran remains firmly committed to Atlanta Hartsfield, the world’s busiest airport where it is the second largest carrier. Much of the growth over the past two years has focused on Atlanta, most recently to boost frequencies in key business markets.

Most significantly, the carrier began serving New York LaGuardia at the end of 1997, after testing that market briefly (just before its grounding) in May 1996. This time around, it had adequate slots thanks to the DoT’s intervention. According to analysts, the six–per–day service has been successful.

But the strategy of operating non–stop flights between Orlando and various points in the Northeast turned out to be a mistake, as the low frequencies did not attract sufficient traffic in those fiercely competitive markets. In September AirTran discontinued all Orlando non–stops except for its 11 daily flights to Atlanta, so all Orlando traffic is now routed via the main hub.

In that same month, AirTran also eliminated all service to five smaller cities (Allentown, Des Moines, Islip, Syracuse and West Palm Beach) in favour of boosting frequencies in bigger and more profitable markets and introducing new service to Newark, Miami and Quad Cities/Moline from Atlanta. The carrier said that the benefits of this major schedule realignment would not be fully realised until early this year.

In an interesting new move, the company has announced a joint marketing partnership with Beau Rivage Resort to operate daily non–stops to Gulfport (Mississippi) from six major Southeast cities from mid–March, to coincide with the opening of a $675m resort. But otherwise the new leadership looks likely to continue to focus resources on Atlanta, where AirTran has 18 gates and the ability to expand to 22.

Going up-market

AirTran’s new post–merger strategy of catering better for the business passenger was broadly in line with the strategies already adopted by low cost carriers like Reno and Frontier. It includes a “no–frills” business class which offers larger seats, more legroom and assigned seating, plus full refunds in the case of cancellation (none of its fares have round trip purchase or Saturday night stay requirements), for a $25 fare supplement on non–stop flights and $40 on multi–stop flights. AirTran has also joined all major CRS systems and begun paying commissions to travel agents.

In an innovative and aggressive approach to boosting customer loyalty, a year ago the carrier began offering an FFP that gives passengers the option of redeeming awards on 14 competing airlines. Since AirTran does not have agreements with the other airlines, it has to purchase the award tickets on the open market.

But is going up–market producing benefits for AirTran? It is probably too early to tell, though yields have improved and in June last year, when the carrier had completed the installation of business class seating, it won Entrepreneur magazine’s 1998 award for “Best domestic low–fare airline”.

Like its competitors, AirTran probably felt that it did not have much choice, because the environment has changed and it is no longer possible to compete as a pure low–cost, low–fare, no–frills, ValuJet–type shoestring operation. But the carrier is not abandoning its basic low–fare strategy and leisure market orientation — it likes to think of itself as an “affordable fare airline”.

Although analysts were initially sceptical about the business class strategy, many now believe that that is precisely where low–cost carriers can make the biggest impact. This is because the major carriers can easily offer just as low leisure fares but cannot afford to match the low cost carriers’ business class fares.

Like many other low–cost carriers paying extremely low wages, AirTran has seen its workforce unionise in recent years. Since 1994 its pilots, mechanics and flight attendants have all voted to be represented by various unions. The pilots and the mechanics never posed problems because they were offered satisfactory overall compensation packages.

But relations with the flight attendants, who are among the lowest–paid in the industry and were previously refused the same benefits and provisions as the pilots, have always been difficult. Tentative agreement on a first contract was reached in early September, but only after the flight attendants had reached the end of their tether after three years of unsuccessful, federally–mediated negotiations and were threatening work slowdowns and stoppages.

The four–year deal, ratified by union members, granted an immediate 10% pay increase, 4% annual rises and longevity increases. AirTran’s 500 flight attendants also secured the same per diem rates, vacation and sick pay, merger protection and grievance procedures as the pilots.

Prospects

AirTran’s immediate priority now is to become profitable, and analysts believe that will be achieved in 1999 thanks to last year’s restructuring and marketing initiatives. The current First Call consensus forecast is a net profit of about $6.5m for the second quarter and marginal profits for the third quarter and the year, followed by a $23m profit in 2000.

But there could be some further restructuring to avoid a cash crunch. AirTran’s CFO Dick Schroeter indicated recently that the cash flow may not be sufficient to cover the costs of owning and operating the planned fleet. It is not clear whether this might mean order cancellations or deferrals — at this stage the airline is merely talking about selling some excess aircraft to raise cash. As is the case with Frontier at Denver, AirTran’s biggest asset is probably its Atlanta hub. But it now has a leaner and much more aggressive Delta to compete with, as well as Delta Express and more East coast–oriented Southwest. Like other low–cost new entrants, AirTran will have a hard enough job coping with legitimate competition, let alone practices that may be predatory.