British Midland: sweating its assets, but where next?

March 1998

British Midland is a relatively small airline yet has managed to challenge British Airways in the lucrative business travel market — and turn in a steady stream of profits at the same time. But what does the airline do now — more of the same, or, given that it has just applied for long–haul routes to the US, are there other viable strategic options?

British Midland Airways is the UK’s second largest scheduled airline, with 14% of all slots at London Heathrow (although its head office is in the Midlands). British Midland’s history can be traced back to 1938 but it was only in the 1980s — when the airline successfully appealed for the right to operate services in competition with British Airways out of London Heathrow — that the airline became a major player. The first European services began in 1986 (to Amsterdam), and today the airline operates 41 aircraft to 19 European destinations.

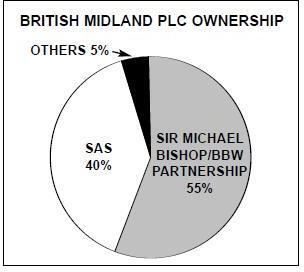

The airline employs 4,750 and is a 100% subsidiary of British Midland PLC, formerly known as Airlines of Britain Holdings. This is controlled by Sir Michael Bishop, via the BBW Partnership (in which he has two other partners). SAS bought a 24.9% stake in ABH in 1988, which increased to 40% in 1994.

The holding company also owns a number of other companies, most of which are aviation–related. In March 1997 the group de–merged British Regional Airlines (Holdings), which includes Business Air, Manx Airlines and Loganair. According to Austin Reid, British Midland PLC’s managing director, this was because these airlines followed a different strategy to British Midland Airways, which may have led to some conflict in the future. Now British Regional Airlines is owned directly by BBW Partnership and operates independently to British Midland PLC.

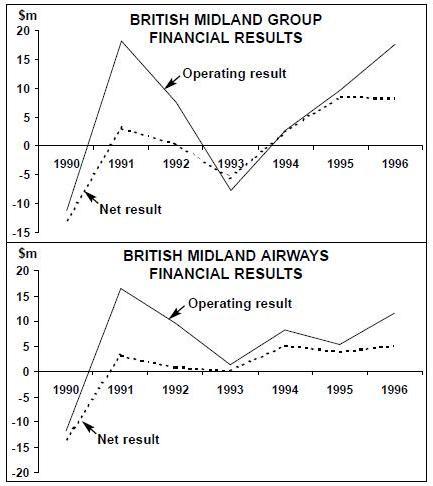

Even before the sale of these airlines, it was British Midland Airways that was the core of British Midland PLC. In 1996 more than three–quarters of the holding company’s revenues came from the airline, as did 65% of operating profit and 60% of net profit. In turn, 88% of the airline’s revenue ($739m in 1996) comes from scheduled passenger services, and only 5% derives from charters and leasing. (The rest comes from aircraft handling services, cargo, duty free sales etc.) 43% of revenue is earned on domestic UK routes.

Slot power

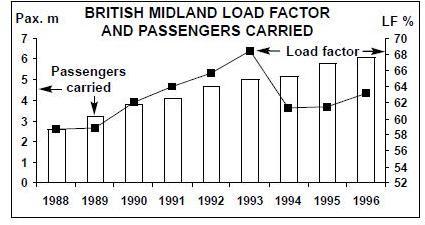

The airline has managed to post respectable operating and net results since the early 1990s (see graphs, right), but Reid is keen to improve the operating profit margin (1.6% in 1996). British Midland’s strategy to improve margin is twofold — to trim costs where possible and, more importantly, to sweat key assets.

These key assets are its slots; therefore the immediate strategic goal for the airline is to maximise return on these slots (while acquiring new slots where it can). In practical terms that means adjusting its portfolio of routes, so that the airline launches routes that it believes will be more profitable than the worst–performing of its existing routes. A prime example is London Heathrow–Manchester, which is launched later this month (on March 29). British Midland claims that this is currently the largest volume route in Europe (one million passengers per year) where the customer has no choice of airline. British Midland will operate eight return flights per day, using 737–500s.

This service will use slots freed up by British Midland’s withdrawal from a Zurich service on March 28 (where Reid says the airline was never allowed to put in place the product it wanted, with the result that break–even would have taken as much as five years to achieve).

British Midland’s target on Heathrow- Manchester is a 35% market share, and break–even within a short period of time. Although the route will initially be flown by two 737–500s, they will be upgraded to A321s as demand grows. If British Midland is successful in winning 35% of a million passengers a year market, it is not likely to please British Airways. Nevertheless, Reid does not expect BA to respond by lowering fares. Although British Midland is promoting a headline price differential with BA’s fares, in reality fare structures and levels are not that much different.

In any case British Midland has clearly signalled how it would react to a fare war — it would retaliate in kind. BA is much more likely to be concerned about loss of feed than direct revenue loss, and airlines flying onwards from Manchester will now have a choice of code share partners.

Outside the UK, the main gaps in British Midland’s European network are to Italy (Milan and Rome) and Spain (Barcelona and Madrid). British Midland did exercise fifth freedom rights via a London Heathrow–Cologne/Bonn–Rome Fiumicino route last summer, but for all new routes the slot problem is ever–present.

Where next?

Over and above asset sweating and cost control, what are the options for British Midland in the medium–term? Reid says there are two obvious choices — the first of which he calls "the BA strategy". This is to take the less critical routes and switch them to other airports, thus freeing up slots at London Heathrow. The second is to start up an entirely new operation at another airport. The problem with the first option is that, for British Midland, its "less critical" routes depend on connecting traffic, of which there would be little or none at other airports.

And starting up elsewhere is not a viable option either — at least not with anything approaching lowish costs. A few years ago British Midland ran the numbers on whether to start or convert to a "low–cost" operation. Its analysis found that low–cost airlines need four conditions: cheap aircraft, good deals with airports, cheap labour and direct bookings.

The first and last of these conditions would be no problem for British Midland, but existing labour agreements would make the third condition difficult to achieve, and as for cheap, or even cost–free deals with airports, Reid believes that first–mover advantages are considerable. The days of low–costs persuading second–tier airports to grant almost free access are gone, particularly now that Ryanair is showing a profit. "Airports want to reclaim some of that margin," says Reid. So British Midland decided against the low–cost route, and moved into the business market instead, where margins are more robust.

As for the challenge of low–costs to British Midland itself, Reid says that the airline is not afraid of competition, and that it will compete vigorously wherever challenged. Competition stimulates the market, he says, although there is some evidence that after an initial market uplift passenger flows do slow down. But he is sceptical about the challenge of the low–costs long–term. BA can afford to gamble $80m on Go, but Ryanair aside, there is very little evidence that the UK and Ireland–based low–cost operators are making money. And Reid questions how airlines like easyJet can afford such vast aircraft orders.

So, if starting operations at other airports is ruled out, what other options are available to British Midland?

Alliances and/or long-haul

One possibility is a major alliance or alliances. British Midland has never been big on alliances, over and above tactical code–sharing on specific routes. It code–shares with 17 airlines at Heathrow, including part–owners SAS and, from April 1997, Lufthansa. The SAS connection alone has very tangible benefits — in 1996 British Midland had net receipts of $11m from SAS for interline billing, handling and other services, but the biggest code–sharing benefits come from United. With the Lufthansa code–sharing the Star alliance is the obvious candidate if British Midland decided it did want to move from tactical code–sharing to strategic alliance.

Talks are ongoing with Lufthansa, particularly about British Midland operating some Lufthansa routes. But the chances of an agreement recede as Sterling strengthens against the Deutschmark, thus reducing the differential between the lower UK cost base and the higher German one. Nevertheless, Reid says that British Midland is “clearly closer to Star than any other grouping”. However, with its strong position at Heathrow, it makes little sense for British Midland to tie itself to an exclusive alliance, however strong the partner(s).

A key determinant of British Midland’s alliance strategy (if it decides to have one) will be the outcome of the BA/AA saga. Open skies between the UK and US would transform the transatlantic market, and on February 24 the airline applied to the UK CAA for route licenses to 10 destinations in the US. The proposed routes would be flown on the slots that BA would have to give up in order to allow the BA/AA tie–up to go ahead. If the application is successful, British Midland would use long–haul aircraft delivery slots freed up by Asian airlines.

But applying for routes is not the same as flying them. According to Reid, British Midland would prefer to wait 3–5 years before launching medium and long–haul routes. Even with open skies it would take 12–18 months before the first British Midland aircraft departed for the US. And if UK/US open skies does occur and if British Midland also joins Star, there could be complex route swapping between the Star partners.

The long–haul application raises the question of whether the airline would be able to make major and instant strategic leaps if it had to. British Midland has made all the right moves so far, but only after extensive analysis of situations. Is the airline’s culture flexible enough to react to major change such as a UK/US open skies deal? The long–haul application would suggest that it is, but the impression is that the airline would not be prepared to risk its steady stream of profits by making major gambles.

The business market

Another key question for British Midland is whether it can retain competitive advantage in the business market. With the launch of Diamond EuroClass in 1993, British Midland became the first airline to offer a separate business cabin on all its European routes, at headline fares up to 40% cheaper than rivals'. With subsequent product and fare enhancements, such as the Diamond Club FFP or the Diamond Pass season ticket, British Midland has worked hard to maintain its reputation among business travellers. In addition, Diamond EuroClass was upgraded in 1996 and introduced onto UK domestic routes in October 1996.

Following analysis, the airline concluded that business travellers are prepared to pay a little extra for a better business class product. But while business customers appreciate all the extras that, say, Diamond EuroClass can deliver, what they really value — and what they are prepared to pay a margin for — is what Reid calls "space". That means space on the ground — i.e. a segregated business lounge — as well as space on the cabin. Hence British Midland’s decision to go from six–abreast to five–abreast.

This can cause short–term pain, as on peak routes revenue is foregone, but British Midland sees a longer–term gain in customer loyalty, which leads to added margin via the concept of customer lifetime value. The only problem for British Midland is that if its analysis is correct, the idea of space could easily be copied by BA (although BA has not yet followed British Midland’s two–class domestic UK service). British Midland would then have to find other business class innovations.

But at least British Midland is helped (so far at least) by the reputation that Sir Michael has built up for being the business travellers’ champion, battling away to increase choice on some of Europe’s busiest routes. It’s a shrewd image, but sceptical observers may detect a hint of Branson–type hype in the image Sir Michael puts forward.

Reid believes a boost will be given to its business class service by new Airbus equipment. The $1bn deal was signed in July 1997, for 11 A320s and 9 A321s (subsequently increased to 12 and 10 respectively), to be delivered over 1998–2003. Four of each type will be bought direct from Airbus and the remainder will be acquired under a lease agreement with ILFC. The airline often mixes and matches leasing and purchasing in order to achieve the right balance of both cash flow and balance sheet effect. In March 1996 it purchased seven 737–500s it had previously leased, but only a few months' later — in May 1996 — it sold and leased back four of the same aircraft.

The fleet decision came down to the A321 versus the 757 (and depending on that decision, A320s or 737s would also be ordered). Reid says he likes to think that the A321 was chosen solely because it was the best operational choice, but he admits that price too was a factor. But even if Boeing had beaten Airbus on price, British Midland would probably have gone for Airbus anyway due to flight deck commonality between the A321 and A320. In any case, says Reid, "BA has the 757, so the A321 is yet another point of differentiation". On the turboprop front, on March 29 the airline is launching a sub–brand, British Midland Commuter, which will use Saab 340s on existing British Midland routes and some ex- Business Air routes.

The future

In the medium–term, British Midland’s profit improvement will continue. In the ten months to October 31, 1997, airline turnover increased 16% on the same period in 1996 and passengers carried rose by 7%. Passenger load factor increased 2.8 points to 70.1%. According to Reid, British Midland will report pre–tax profits for 1997 of "at least” $24.5m, compared with $9.5m in 1996.

Longer–term, however, there remains one key question — what will become of British Midland, both the airline and the group, once Sir Michael Bishop retires? Just when Sir Michael will exit from his shareholding is anyone’s guess, but the form it takes could have a tremendous impact on the future of the airline. For example, SAS has pre–emption rights and might have very different plans for British Midland if it took control. On the other hand, a flotation might pressure management into short–term profit maximisation.

But all this is no more than speculation, and until the day Sir Michael retires British Midland is likely to continue its steady, if conservative, progress.

| Current fleet | Orders (options) | Delivery/retirement schedule | |

| Saab 340s | 6 | 0 | |

| Fokker 70 | 3 | 0 | |

| Fokker 100 | 6 | 0 | |

| 737-300 | 8 | 0 | Precise plans for the 737 fleet (i.e. how |

| 737-400 | 5 | 0 | many will be kept and how many will be |

| 737-500 | 13 | 0 | released) have yet to be announced. |

| A320 | 0 | 12 | From April 1998 to 2003. Four from |

| Airbus and eight on lease from ILFC | |||

| A321 | 0 | 10 | From April 1998 to 2003. Four from |

| Airbus and six on lease from ILFC | |||

| TOTAL | 41 | 22 |