TWA: burning fewer dollars, but can it make a profit?

March 1998

TWA is still reporting losses, but recent operating improvements and successful cash–raising efforts have given it a new lease of life. Is the carrier now set for financial recovery and are its longer term prospects any better?

TWA emerged from the first of two Chapter 11 reorganisations in November 1993 with reduced debt, $200m cash and no labour problems, but by the following summer it was again in a sorry state. It was over–leveraged with a high cost structure, an old fleet, antiquated operating systems, a weakened route structure, a tarnished market image and an unfocused competitive strategy.

An eight–week Chapter 11 reorganisation in the summer of 1995 accomplished some meaningful financial restructuring, even though long–term debt remained at a substantial $1.26bn. For a while it looked like TWA was staging a recovery, but the process came to a halt in the second–half of 1996 because of over–ambitious expansion, operational problems, the tragic crash of Flight 800 and renewed management turmoil.

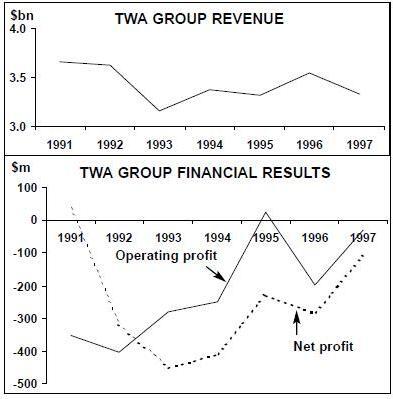

The combined effect of all of that, plus the hike in fuel prices (which hit TWA hard because of its old fleet), was to cause costs to soar and the yield to plummet, sending the company into a tailspin from which it seemed incapable of recovering. TWA made a net loss of $285m in 1996 and a net loss of $111m in 1997, bringing the total net losses accumulated since 1989 to $2.4bn.

Throughout much of last year the company was in an almost constant cash crisis. In March it was rescued by a St. Louis business organisation, Civic Progress, which made a $26m advance purchase of tickets. TWA also received a surprise confidence–booster when Prince al–Waleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia purchased 2.1m of its shares (about 4% of the total) on the open market — a purely speculative move taking advantage of the rock–bottom share price.

These expressions of confidence in TWA’s future helped the company raise $50m in a private offering later that month, enabling it to scrape through the remainder of the winter season. But as losses continued, it finished the second quarter with only $103m in cash, down from $304m a year earlier.

The situation became alarming when TWA failed to build up its cash reserves in the peak season. It entered the fourth quarter with a cash balance of just $105m. Since it traditionally burns through $100-$170m of cash in the October–March period, the chances of making it through the winter seemed pretty slim indeed.

However, operational performance began to improve in the late summer and TWA actually reported a sharply improved $64m operating profit and a marginal $6m net profit (up from a $14m loss) for the third quarter. And, during the final months of the year it became increasingly evident that a recovery was under way.

Although operating and net losses were still reported for the full year ($29.3m and $110.8m respectively), TWA turned in a marginal $0.5m operating profit for the fourth quarter, compared to a $232m loss a year earlier. The $31m net loss, which included $10m of special charges, represented a massive improvement over the previous year’s $263m loss.

The gradual reduction of debt since December 1995 had freed up enough collateral for TWA to raise funds through asset–backed securities late last year. The company completed three transactions in December 1997, raising $326m, $178m of which was used to refinance debt and to pay or prepay interest, leaving a useful $148m cash cushion.

At the end of December, TWA had $237.8m in cash reserves which, assuming that operational performance continues to improve, is probably enough to last at least until the next economic downturn.

Although TWA’s debt now again exceeds $1bn and its credit ratings are still in the junky CCC–CC range, S&P’s recent decision to upgrade the ratings outlook from "negative" to "stable" is a promising sign.

An added benefit of the December financings was the ability to repay the remaining $60m debt to Icahn–affiliate Karabu Corporation (a total of $190m was originally borrowed in 1993). However, the company could still not totally shake off its former owner Carl Icahn as he has rights to buy and resell discounted TWA tickets.

TWA’s share price rose sharply in early December 1997, from the $6-$8 it had hovered at since late 1996 to a high of $11.50-$12. After briefly falling to around $10-$10.50 in the early part of January, the shares soared to over $13 after the fourth–quarter earnings were released on February 13. The Saudi prince’s original $14m investment in TWA has roughly doubled in value in 11 months.

The company attributes its "dramatic operational turnaround" mainly to the past year’s efforts to renew and right–size the fleet, as well as improved operational reliability and numerous initiatives designed to attract full–fare passengers.

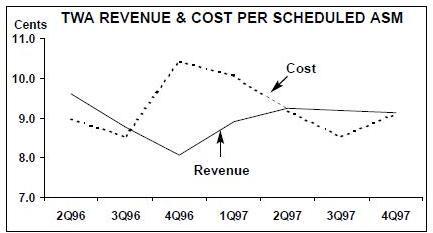

The biggest improvements were on the revenue side. While capacity and operating costs fell by 10.2% and 21.6% respectively in the fourth quarter due to fleet downsizing and other cutbacks, revenues actually rose by 1.2%. This was primarily due to an 8.6% surge in yield, though a four–point rise in the passenger load factor, to a respectable 66.8%, also helped.

The positive trends have apparently continued in the current quarter and TWA expects its cash burn to be roughly half of last year’s level. According to First Call, analysts currently estimate the first–quarter net loss to be somewhere between 40 and 70 cents per share, down from last year’s $1.51. Through the first half of the year, comparisons will also be helped by the fact that in the same period in 1997 a lot of aircraft were out of service.

But to what extent have the economics of TWA actually improved? Has it restructured itself sufficiently to become profitable and catch up with the other major US carriers?

Fleet renewal and right-sizing

About a year ago TWA decided to phase out its inefficient, old 747s and L–1011s and substitute the smaller, newer 767s and 757s on transatlantic and transcontinental routes. This process is now complete — the last L–1011 retired in September 1997 and the last 747 on February 20 — and the benefits in terms of yield and load factor improvement will continue to be felt through the best part of this year.

Most other US carriers retired their domestic widebodies years ago, so TWA is a little late in the game. Downsizing aircraft on the Atlantic routes makes particularly good sense for TWA because it previously had to carry what it described as "junk yield traffic from all across America" to fill the 747s. Now the smaller 767s can be filled with higher–yield traffic from the New York area.

The lack of a larger widebody will limit the carrier’s future expansion opportunities in long haul markets — the 767 is not ideal for the Honolulu or the hoped–for Tokyo route — but the yield and other benefits in most existing markets obviously outweigh that disadvantage.

TWA is in the process of taking delivery of $2bn–plus worth of new or recent–vintage aircraft. Deliveries of 20 ordered 757s began in 1996 and 12 arrived last year. A new 767–300 has just joined the fleet and another will arrive in March (15th and 16th, both on lease from ILFC). The carrier also began taking delivery of 15 new and nine almost–new MD–80s last summer, while continuing to hush–kit its DC–9–30s.

The impact of the 747 and L–1011 retirements and the addition of 26 new aircraft last year was to reduce the average age of TWA’s aircraft from 19 to 17 years — still some way to go to catch up with competitors. Twelve new aircraft are currently contracted for delivery this year, though there will apparently be more.

After last year’s 10.2% capacity contraction, which was sharpened by the route cutbacks, TWA expects its ASMs to decline by 4% in 1998. This is mainly due to the L–1011 retirements, and domestic capacity will start to inch up in the fourth quarter. However, there will be a similar (4%) rise in the number of departures, in line with the aim of offering a better service for the full–fare traveller.

Yield-boosting efforts

Yield has been one of TWA’s main problems in recent years — it used to have a strong brand name but lost it gradually due to a host of factors.

The carrier has tried hard to remedy the situation over the years but to no avail. It blamed the second–quarter 1997 losses squarely on its inability to "reclaim its share" of the premium fare business travel market.

Much of the current turnaround must be attributed to TWA’s remarkable success in improving its on–time performance, which, along with convenient schedules, ranks high among business travellers' priorities. TWA moved up from last position in 1996 to second position in 1997 in the DoT’s domestic on–time performance rankings. It actually came first in the second and third quarters.

Many of the US carriers have focused heavily on the business passenger over the past year or two but TWA’s efforts since the summer really stand out. Most significantly, the carrier decided to reconfigure its 155–strong domestic narrowbody fleet to offer 60% more first class seats (mainly to improve passengers' chances of securing an upgrade). The move meant no overall reduction in the number of seats because new slimmer first class seats were installed and the coach class seat pitch was reduced.

Since the MD–80 part of the programme has only just been completed and the DC–9 part is just beginning, the results will be seen in the current year. However, TWA has reported a measurable increase in first class revenues as the reconfigured aircraft entered service and even before the product was properly marketed.

The other first class incentives already introduced or under way include new domestic menus, FFP enhancements, revamped Ambassadors clubs at St. Louis, JFK and LaGuardia, new ticket counters and check–in areas and numerous improvements at JFK’s Terminal 5.

TWA is now going for an "all–out marketing push" to improve its share of business traffic in 1998. It began marketing the new Trans World First domestic product in mid–January. The FFP will be completely relaunched in the near future. This month (March) the carrier will launch a new branded business class product that offers shuttle- type service in eight or so business markets out of St. Louis.

The recent trends suggest that TWA is closing the historical yield gap with its competitors. In the fourth quarter of 1996, its yield of 11 cents per RPM was way below the 12–13 cents reported by the six largest carriers. Now its yield (12.02 cents in the fourth quarter) is virtually the same as Northwest’s and not that much lower than US Airways' 12.36 or United’s 12.51. The gap will narrow further if TWA achieves its 10% yield improvement target this year — not an unrealistic proposition in the light of its current efforts.

Costs and productivity

TWA’s decision in December 1996 to reduce transatlantic and some domestic services out of JFK in January was an emergency measure aimed at stemming huge losses and conserving cash in the winter months. The move involved consolidating activities at JFK into one terminal and furloughing about 500 workers. The company hoped that the cutbacks would generate cost savings to the tune of $400m annually — exactly the amount that total operating costs fell in 1997.

The fleet changes prompted another round of 1,000 job cuts in the second half of last year. This involved furloughing some 450 mechanics (as 23 domestic line maintenance stations were consolidated into 13) and eliminating 550 positions in airport operations, reservations and other areas through attrition. However, that may be the extent of the cost cuts for the time being at least.

Unit cost reductions do not feature in TWA’s recovery plans, which is understandable as capacity cuts and fleet downsizing tend to have a negative impact in that respect. TWA’s costs per ASM rose from 8.76 cents in 1996 to 8.97 cents in 1997. The focus now is clearly on productivity improvements.

The biggest challenge on the cost side is to ensure the continuation of favourable labour agreements, which may no longer be possible in the current industry climate. All of TWA’s union contracts became amendable in September and the long–suffering workforce has been angered by the past year’s furloughs. Talks with the pilots are reportedly not going well, and the flight attendants are likely to adopt a tougher stance now that they are represented by the more powerful machinists' union.

Structural problems

The past year’s network restructuring efforts have involved downsizing the loss–making JFK hub and strengthening further the profitable St. Louis hub, which TWA believes still has some growth potential.

The JFK moves have won much praise from outsiders, particularly since they have been accompanied by measures designed to improve image and yields — it is just a pity that those actions were not taken earlier.

However, the cutbacks have enabled competitors such as Delta to further strengthen their positions in the transatlantic market. It seems that, despite the continuing investment in JFK facilities, that hub is becoming less important for TWA with every passing day.

After years of trying, TWA has only managed to secure two relatively insignificant (though high–quality) transatlantic partners, Air Europa and Royal Jordanian, and can therefore not compete effectively with the mega–carrier alliances that may build up operations via the important JFK gateway. TWA may find itself in the difficult predicament of needing to pull out but not knowing how to deal with the employee problem. One of the most significant new achievements at St. Louis is the elimination of seasonal fluctuations. Because of the heavy reliance of east–west traffic, TWA’s operations have traditionally been more seasonally peaked than those of other major carriers. The peak summer day/trough winter day capacity variance used to be as high as 50%, but increased north–south flying reduced the variance to 25% in 1996 and the aim now is to effectively eliminate it (4%) this year.

While TWA has succeeded much better than expected in developing a lucrative Midwest franchise and retaining a dominant position at St. Louis, the strategy has only limited potential. Increased reliance on a single hub makes the carrier vulnerable in the longer term.

The next move?

TWA’s immediate priority now is to become profitable, but there is no clear indication as to when that might be achieved. The uncertainty is illustrated by the wide disparity in analysts' estimates: the three brokers reporting on TWA to First Call predict the company’s 1998 earnings to be anywhere between a loss of 50 cents per share and a profit of 80 cents a share.

The key question is: can TWA move fast enough to take advantage of the current economic boom? If it cannot make money in this environment, it has no hope of surviving a downturn.

But even if it stages a sustained recovery, TWA’s long term fundamentals have not changed. Its limited route structure and weak balance sheet make it an unlikely long–term survivor.

TWA needs a domestic alliance probably more than any of its competitors. It is not at all attractive as an equity partner at present because of its weak balance sheet, high share price, old fleet, unusual governance structure and tough contract negotiations with the unions. But since many potential partners are interested in the St. Louis hub and TWA’s image has clearly improved, there seems no reason why domestic code–share and marketing cooperation could not be implemented.