Air Arabia versus Flydubai

and Abraaj

June 2019

Air Arabia’s record of profitably since its inception 16 years ago was shattered in 2018 when it reported a net loss of AED 579m (US$156m). However, the cause of this loss was a one-off write-off of its investment in Abraaj Group, a private equity fund, totalling AED1.1bn ($300m).

Air Arabia is a conservative company, making this write-off even more unusual. But until last year the Dubai- based Abraaj Group appeared to be a leading private equity fund, specialising in health care, clean energy and transport (indeed, it was an early investor in Air Arabia, as well as in Nasair in Saudi Arabia). Its collapse was a major shock with creditors now owed at least $1bn. Disturbingly, accountants PwC’s preliminary investigation found that Abraaj’s revenues hadn’t covered its operating costs for years, and investors’ funds were being used to fill that gap rather than for investment. Another Big 4 auditor, KPMG, had signed off on Abraaj’s accounts for the entire period that this activity was taking place — a sadly familiar story. Now Air Arabia, and many others, are suing the Abraaj founder, Arif Naqvi, in the hope that if any funds are recovered, which is very uncertain, Air Arabia will be able to write them back into its accounts as exceptional profit.

If it hadn’t been for Abraaj, Air Arabia would have recorded a net profit (there is little difference between operating and net profit) of about AED 555m, a 13% margin on revenues, a respectable result though well down of the years of super-profitability a decade ago.

The airline retains many of the characteristics of a classic LCC:

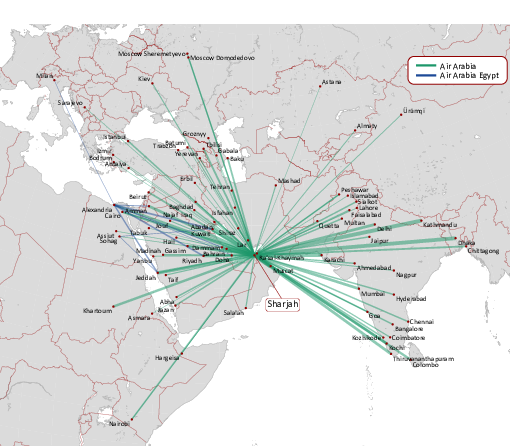

- It operates from a low-cost airport — Sharjah — owned by the Emirate, which retains an 18% stake in the carrier (82% is floated on the Dubai stock exchange). Air Arabia enjoys a dominant position and has an attractive passenger and ground handling contract with the airport authority. Sharjah itself is less than an hour’s driving time to downtown Dubai. Air Arabia is also in the process of building a secondary hub at Ras al Khaimah, another of the smaller Emirates.

- According to Airbus, Air Arabia is the global leader in terms of A320 utilisation — 13 flight hours a day compared to a global average of 8.8 hours. Sharjah — like other airports in the region — operates 24 hours a day, so Air Arabia can schedule an overnight trip to, for example, Colombo in Sri Lanka after operating flights in the Gulf region throughout the day. Dispatch reliability at 99.7% is also one of the highest in the industry.

- The product is of good LCC standard: aircraft are configured with 162 economy seats (a bit below the maximum for A320), which allows a 32" pitch, which is slightly better than the average space for economy products in the region. Load factor is around 81%. Meals are sold on board but there are no alcohol sales as Sharjah is a dry state, which limits ancillary income, which is only about 5% of total revenue.

- Air Arabia has had to operate in a regulatory regime that is largely based on bilateral ASAs, although the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) states do have an open skies regime. But Air Arabia is also a flag-carrier of the UAE (along with Emirates, Flydubai and Etihad), which greatly facilitates its negotiating position.

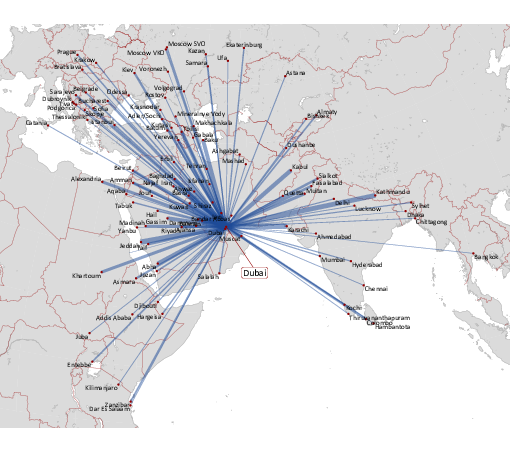

Air Arabia’s big challenge has been the emergence of Flydubai as Dubai’s own LCC. Although not a subsidiary of Emirates Airline, the two airlines are both owned by the state, and since 2017 have offered a connecting service at DXB which now covers 84 mutual destinations.

As the graphs indicate, Flydubai has been outpacing Air Arabia in revenue growth — from 2102 to 2018 Flydubai increased turnover from AED2.8bn to AED6.2bn while Air Arabia’s revenues grew from the same total, AED2.8bn, to AED4.1bn. However, this is a little misleading as Air Arabia has been growing at its Associates’ bases — Air Arabia Morocco, Air Arabia Jordan and Air Arabia Egypt — and has leased out 13 of its aircraft to these airlines. As Air Arabia holds a minority stake in these airlines, (40-49%), they are accounted for on an equity basis, ie their proportionate profit contribution shows up in Air Arabia’s accounts, not their revenues. (Only Morocco makes a profit, and Air Arabia’s share of that was only AED27m in 2018.)

In 2018 Flydubai carried 11m passengers while Air Arabia flew 8.7m, but it claims over 11m in total when the Associates are included. From airports less than an hour apart, the two airlines operate very similar networks — see maps.

Flydubai has never achieved the same level of profit margin as Air Arabia, averaging 5-6% in the early 2019s when the financial results were unaudited. In 2018 it reported a net loss of AED166m, a -3% margin on revenues of AED6.2bn, blamed on fuel prices,

A tentative comparison of Air Arabia and Flydubai 2018 results shows Air Arabia’s average fare to be 18% below that of Flydubai, which has a business class on its flights. Total revenue per passenger was about 14% lower at Air Arabia. On the other hand, Air Arabia has a substantial advantage on the cost side. Operating costs per passenger were 26% lower in 2018.

Flydubai is the second most important 737MAX customer (after Southwest) and currently has 237 units on order. Unfortunately, it has had to park 14 MAXs, and has threatened to cancel and switch to Airbus for at least part of its order. Meanwhile, Air Arabia has announced that it will place an order for at least 100 aircraft this year, probably a combination of A320s and A321s.

So together Flydubai and Air Arabia will have a firm order commitment of about 340 narrowbodies by the end of the year compared to their current A320/737 fleets of 59 and 55 units respectively. Although some of the new orders will be for replacement, this does look like potential over-capacity in a market which has reverted to much more modest traffic growth and where the super-connectors are going through a painful rationalisation process. And when the MAXs and A321s eventually come fully into service, the two LCCs may find themselves in direct competition on longer routes with the super-connectors, offering their own narrowbody connecting, or self-connecting, services.