Air Canada: Quest to become

a “global champion”

June 2016

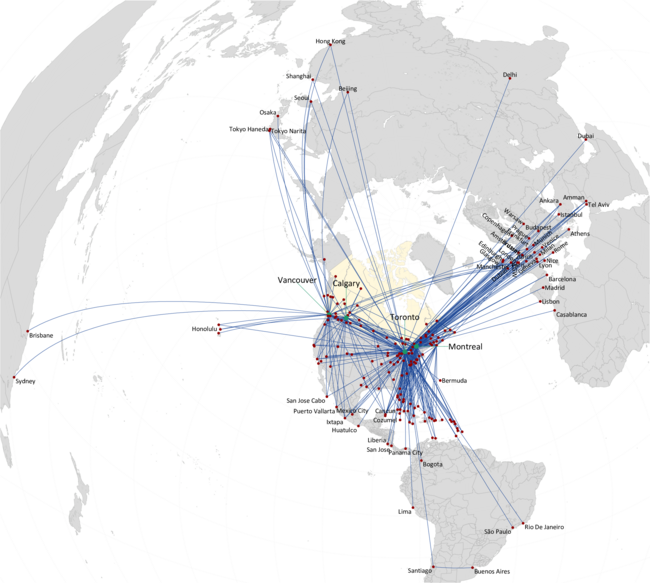

Air Canada and its lower-cost unit Rouge are in the midst of an aggressive international expansion drive. In the past month or so, Air Canada has launched three new intercontinental routes — Toronto-Seoul, Vancouver-Brisbane and Montreal-Lyon — while Rouge has entered seven new seasonal transatlantic markets (Gatwick, Glasgow, Prague, Budapest, Warsaw, Dublin and Casablanca). Since early May Air Canada has also launched 11 new US transborder routes, including four new US destinations.

Furthermore the strategy of trying to capture sixth freedom traffic between the US and Asia/Europe via Toronto and other Canadian hubs has gone into overdrive.

At a time when capacity restraint is the name of the game among global carriers, Air Canada is unashamedly going after market share. The management admitted it in the latest quarterly earnings call. One of the executives noted that Air Canada had ceded a lot of market share to foreign carriers in the past and now intended to recapture it.

Air Canada feels justified in stepping up growth because it has staged an impressive financial recovery since 2009 and has continued to meet or exceed its financial targets. The company insists that “sustained profitability” remains its key long-term goal.

Thanks to a combination of reduced costs, best-in-class premium offering and the “right transit programmes in place at key airports”, AC feels that it is well positioned to attract transit traffic. It enjoys network, scale and other benefits that position it well for such a strategy (more on that below).

But the financial benefits are somewhat questionable, especially at a time when the global economy is slowing and fuel prices are on the uptick. Also, although Air Canada is now profitable, its operating margins (10.8% in 2015 and 4.6% in Q1 2016) continue significantly to lag those of its North American peers.

There are three obvious reasons for the margin gap: Canada’s economic slump, a weak domestic pricing environment and the sharp weakening of the Canadian dollar against the US dollar in the past couple of years (though this year has seen a slight rebound). But Air Canada has also benefited from lower fuel prices. In the March quarter, its fuel bill contracted by 25%; yet, because of increases in all other cost categories and a weak revenue environment (systemwide RASM fell 5%), operating profit declined by 23% and adjusted net profit by 30%.

It is not the wisest strategy to embark on what Air Canada describes as its “most intensive period of international expansion” in the current environment. Then again, if one takes a long-term view, the potential payout may justify it.

Amazing transformation

Few global carriers have received as much help as Air Canada in terms of bailouts, restructurings (in and out of bankruptcy), labour concessions and pension relief in order to get their houses in order. After completing an 18-month bankruptcy reorganisation in 2004, Air Canada continued to be plagued by high costs and financial losses. When the global recession hit in 2009, AC almost ran out of cash but managed to pull itself out of that crisis thanks to labour and supplier concessions and some creative financings.

But Air Canada’s subsequent (post-2009) transformation has been nothing short of miraculous.

Calin Rovinescu, who took over as Air Canada’s CEO in April 2009, reminisced in a recent speech how he originally came up with the idea of “global champion” as a topic for a September 2010 speech. He noted that as Canada had just lost many prominent businesses, and given Air Canada’s dismal history, some in the audience thought he was delusional while others wondered what he was smoking.

Rovinescu asked: “Why couldn’t Air Canada, a then 75-year-old company, be capable of really thinking big?” He believed that the key tactics would be to take some risk, play to strengths and be nimble.

The subsequent “global champion” strategy had four core components: cost reductions and revenue initiatives; pursuing profitable international growth opportunities; enhancing product/service differentials; and fostering cultural change.

Air Canada has made great progress on all of those fronts. There was an initial programme targeting C$530m of cost reductions and revenue enhancements in 2009-2011, but progress has been particularly swift since 2012 when more initiatives were adopted — boosting aircraft utilisation, ordering more efficient aircraft, setting up a lower-cost airline subsidiary and revising the contract with regional carrier Jazz.

The two most important moves have been, first, the introduction of the 787. There were 16 in the fleet in March, with 21 more to come by the end of 2019 (see fleet table). The type offers significant efficiency improvements over the 767-300ER and has opened up new opportunities for profitable growth.

Second, Air Canada set up Rouge in 2012. The unit first flew in July 2013 and has grown rapidly to 41 aircraft, operating 99 routes to 70 destinations. It has been deployed mainly to the Caribbean and European leisure destinations but also to Africa (Casablanca), South America (Lima), Asia (Osaka) and selected leisure-oriented routes in Canada and to the US. Some of the routes have been transferred from Air Canada but many have been new.

Rouge was a risky endeavour, given the potential fallout for Air Canada’s premium brand and conventional offerings and the dismal history of low-cost units operated by legacy carriers. But the venture has exceeded management expectations. It has enabled Air Canada to maintain or expand its existing leisure routes and enter new markets, and it has contributed to profitability.

Air Canada has said that Rouge offers 25% lower CASM compared to the mainline fleet. The cost savings arise from higher seat density, lower wage rates, more flexible work rules and reduced overhead costs. Also important is the coordinated approach that leverages the strengths of Air Canada, Rouge and Air Canada Vacations.

The problem now is that Rouge is nearing it maximum permitted size. Under a 2014 agreement with Air Canada’s mainline pilots, the unit is allowed to operate up to 50 aircraft (25 767s and 25 narrowbody aircraft).

Another profit-enhancing project is refurbishing the mainline 777-200/300ER and A330-300 fleets with new interiors and adding a premium economy cabin. The move will improve the economics and provide a product consistent with the 787’s. The 777 conversions were due to be completed this quarter, with the A330s following in the next 6-9 months. Air Canada expects to recoup the C$300m cost within three years.

Narrowbody fleet renewal from 2018 will also help reduce costs. Air Canada has an order in place for 61 737 MAXs, which will arrive from late 2017 through 2021, plus 48 options. The type will replace the mainline A320-family fleet, resulting in an estimated 10% CASM saving.

The airline is also targeting some narrowbody cost savings in the interim period. It is leasing some additional A321s and A320s so that 20 E190s can exit the fleet, and it is retaining five 767s that had previously been slated for retirement this year. Added together, those two moves will drive a 10% CASM reduction.

Continued cost reductions are critical because Air Canada’s yields and unit revenues will remain under pressure for the foreseeable future because of the increasing average stage length, expansion in leisure markets and a higher percentage of connecting traffic.

Air Canada has reduced its unit costs by 9.3% since 2014 and is apparently on track to meet its target of a 21% reduction in CASM between 2012 and 2018 (excluding the impact of foreign exchange and fuel prices).

Key revenue initiatives include a new passenger revenue management system, which is expected to boost profits by C$100m annually when fully implemented. And there remain opportunities to develop ancillary revenues.

As CEO Calin Rovinescu boasted to shareholders at the company’s AGM in May, Air Canada has staged quite a transformation since 2009. Its operating revenues have risen by 40% in the six-year period, from C$9.7bn in 2009 to C$13.9bn in 2015, which is impressive for a legacy carrier. EBITDAR margin has improved from 7% to 18.3%, exceeding the target of 15-18%. Adjusted net income has risen from a loss of C$671m to a profit of C$1.2bn.

In the same period, leverage ratio declined from 8.3x to 2.5x (the target is 2.2x by 2018). And Air Canada now has a pension solvency surplus of C$1.3bn, compared to a deficit of C$2.7bn in 2009.

ROIC was 17.4% in the 12 months to March 31, exceeding the 13-16% target for 2016-2018. Unrestricted liquidity was C$3.2bn (23% of last year’s revenues).

But perhaps the most amazing achievement is the turnaround in labour relations. Achieving a good culture is one of the toughest challenges for airlines; yet, it is critical for the success of a service-oriented company. Air Canada has historically had difficult labour dealings and a culture that was “rule-bound and process-driven”. But, according to Rovinescu, it now has an “engaged” workforce and a “culture of entrepreneurship and performance orientation”.

Air Canada has been named one of Canada’s top-100 employers for three years in a row. It was also recently named one of the best places to work in Canada in “Glassdoor’s 2016 Employees’ Choice Awards”, which are based on a vote by employees. Who would have thought that possible six years ago?

Importantly, Air Canada now has 10-year agreements in place with most of its unions; the key deals with pilots, flight attendants and mechanics were signed in 2015.

It is not entirely clear how such major shifts in labour relations were accomplished, though back in 2010-2011 the management seemed pretty determined to instigate change (see Aviation Strategy, June 2011). Other factors that may have helped: stabilisation of pension plans, resumption of growth and the new career opportunities associated with the global expansion.

The long-term labour deals give Air Canada unprecedented labour stability, and the happy and engaged workforce positions it well for retaining premium traffic.

Becoming a “global champion”

Since 2009 Air Canada has launched nonstop service to more than 30 new destinations around the world. US transborder and long-haul international operations now account for almost two-thirds of its passenger revenues (65% in 2015). That percentage will continue to increase as about 90% of this year’s capacity growth will be international.

One major benefit has been to diversify risk — especially helpful in the past couple of years as Canada’s economic growth has slowed, the currency has weakened and the domestic pricing environment has deteriorated.

Air Canada’s international growth has focused on two specific strategies: competing effectively in the leisure market to and from Canada (which has been accomplished with Rouge) and tapping sixth freedom traffic via Air Canada’s international gateways, especially Toronto and Vancouver but also Montreal and Calgary.

Tapping sixth freedom traffic to and from the US makes much sense because the Canadian domestic market is limited in size and already quite mature. The US market is 10-12 times larger.

Air Canada estimates that at present it has 1% of the international connecting traffic to and from the US carried by non-US airlines. The management makes the point that just increasing that share to 1.5% would translate into 1.68m extra passengers per year or around C$605m incremental revenue.

The sixth freedom strategy is successful and has further potential because Air Canada enjoys the following benefits (in no particular order of importance):

Geographically well-positioned hubs, with efficient transfer processes

Toronto Pearson, Air Canada’s main hub for global traffic, is well located near the centre of North America and in close proximity to the densely populated major markets in the US. The city also has significant local traffic.

There is strong competition for global traffic from rival hubs in New York and Chicago, but Air Canada and the airport authority have worked closely to create a fast and efficient connection process that compares very favourably with the US hubs. For example, the elapsed travel times via Toronto for someone going from Philadelphia to Asia would be “very competitive, if not the fastest”. An added benefit is that Air Canada and its Star partners operate from the same terminal in Toronto.

Vancouver, in turn, is a natural gateway to Asia Pacific, offering some of the shortest elapsed travel times to that region from North America. Air Canada is growing it into a premier Pacific gateway. And Montreal is being “invigorated” as a “francophone hub” — a gateway to French international markets. An example is the recently added five-per-week Montreal-Lyon service, utilising 767-300ERs.

To illustrate the strengths of Air Canada’s four hubs, at year-end 2015 the hubs offered the following total daily departures: Toronto 349, Vancouver 148, Montreal 144 and Calgary 110.

US-Canada open skies ASA

Canadian airlines benefit from a full US-Canada open skies regime. The transborder services were initially liberalised in 1995, and the ASA was further relaxed in 2007 to allow sixth freedom via Canada.

Extensive traffic rights and slot holdings

Canada has extensive traffic rights around the world that in the past were largely unused as Air Canada struggled financially. So now, unlike US airlines in many cases, Air Canada does not have to wait for ASAs to be liberalised; the opportunities are there to be cherry-picked.

Also, Air Canada claims that it benefits from extensive holdings of slots at favourable times at busy airports, including Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Tokyo Narita, Tokyo Haneda, Paris, Frankfurt, London Heathrow, London Gatwick, New York LaGuardia and Washington Reagan.

Canada’s multi-ethnic population

Canada is a common destination for immigrants from around the world and has large communities of different ethnic groups. There are strong historical ties especially with the UK and France. All of that means significant VFR traffic and steady demand.

Scale and network benefits

Air Canada has a strong route franchise and leading market shares in the Canadian domestic, US-Canada transborder and long-haul international markets. In 2015 Air Canada and its units accounted for about 55% of domestic ASMs (compared to WestJet’s 37%), 41% of total ASMs (including US carriers) in the US-Canada market (compared to WestJet’s 20%) and 37% of total ASMs (including foreign carriers) in the Canadian long-haul international markets (compared to WestJet’s 4%).

Air Canada offered as many as 53 US destinations from Canada at year-end 2015 — and that list will grow this year. The mainline, Express and Rouge operations are coordinated to maximise connections. Such scale, dominance and critical mass in North America adds up to impressive connectivity.

Star and transatlantic JV benefits

Air Canada is a founding member of Star and benefits greatly from belonging to what is arguably the strongest of the three global alliances. Other benefits include a revenue-sharing transatlantic JV with United and Lufthansa and codesharing with United in North America.

Superior product and well-known global brand

Air Canada stands out for its industry-leading product offering and service quality. That has been the case historically and the airline continues to maintain the differential; one recent example is the introduction of a “next-generation cabin” in international business class. Air Canada is the only North American airline to offer a true premium economy cabin, and it is the only international airline in North America to be rated four-star by Skytrax.

All of that, in combination with the iconic global brand, bodes well for profitable international growth and for attracting connecting traffic.

New traffic management tools

Air Canada has new tools at its disposal that enable it to pursue international growth opportunities more profitably. In particular, its new O&D management system enables it to “better optimise traffic flows we select to carry, be it point-of-sale in Canada, US or international”.

Solid fleet plans

Air Canada has the fleet plans in place to facilitate robust international expansion. Its C$9bn capital investment programme (mostly on new-generation aircraft) will ensure both sufficient aircraft numbers and one of the youngest fleets in the industry.

In addition to the continuing 787 deliveries and the substantial 737 MAX orders, Air Canada is expected to in the near future firm up an earlier letter of intent for up to 75 Bombardier CS300s (45 firm and 30 options, with some CS100 substitution rights). The first 25 of those aircraft will replace the mainline fleet of E190s; the rest are for growth.

All in all, Air Canada seems uniquely well positioned to grow internationally and attract sixth freedom traffic. But it is less certain that the strategy will help it attain the goal of “sustained, long-term profitability”.

It is a low-yield growth strategy that will require continuous relentless cost reductions. Those in turn depend on rapid fleet renewal and mean heavy capital spending at a time when profitability is not yet that strong and when margins may have peaked. But there is flexibility in the fleet plan (via lease expirations, for example) to slow growth if necessary.

| Year end | |||

| March 2016 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Mainline | |||

| 787-8† | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 787-9† | 8 | 13 | 22 |

| 777-300ER | 17 | 19 | 19 |

| 777-200LR | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 767-300ER | 17 | 15 | 10 |

| A330-300 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 737 MAX‡ | 2 | ||

| A321 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| A320 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| A319 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| E190 | 28 | 25 | 25 |

| Total mainlineφ | 167 | 169 | 175 |

| Air Canada rouge | |||

| 767-300ER | 17 | 19 | 25 |

| A321 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| A319 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Total rouge§ | 41 | 44 | 50 |

| Total mainline & rouge | 208 | 213 | 225 |

| Air Canada Express¶ | |||

| E175 | 20 | 20 | na |

| CRJ-100/200 | 27 | 27 | |

| CRJ-705 | 16 | 16 | |

| Dash 8-100 | 24 | 19 | |

| Dash 8-300 | 26 | 26 | |

| Dash 8-Q400 | 36 | 47 | |

| Beech 1900 | 17 | 17 | |

| Total Air Canada Express | 166 | 172 | |

Notes: † Air Canada has ordered a total of 37 787s for delivery by year-end 2019. ‡ Air Canada has firm orders for 61 737 MAXs for 2017-2021 delivery; the associated narrowbody retirements have not yet been determined. § Rouge can operate a maximum of 50 aircraft under a 2014 pilot deal. φ Air Canada has signed an LoI to acquire up to 75 Bombardier CSeries aircraft for mainline operations for delivery from 2019. ¶ Jazz, Sky Regional and other airlines under capacity purchase agreements with Air Canada.

Source: Air Canada

Note: The results are on a Canadian GAAP basis up to and including 2009; 2010-2015 results are on an IFRS basis. Source: Company reports

Note: equidistant map projection based on Toronto.