Brazil's airlines: Azul and Avianca Brazil rise to challenge Gol-TAM duopoly

June 2013

The Brazilian aviation market has seen significant change in the past year or so, as demand growth has weakened, an unprecedented capacity discipline has taken hold and industry consolidation has reached new heights. Faced with financial losses domestically, the two leading airlines have been restructuring operations and have adopted many new strategies. How are the four main players – Gol, TAM (now part of Latam), Azul-TRIP and Avianca Brazil – now positioned for the remainder of 2013 and for the longer term? Is Azul, which filed for a global IPO in late May, on the verge of becoming a “third force” in Brazilian aviation? Will Avianca Brazil bid for Portugal’s TAP and also become a major player in Brazil?

The past year’s upheavals come in the wake of a tumultuous decade in the Brazilian airline industry. The 2000s witnessed the arrival of Gol as Brazil’s first LCC to stimulate and revolutionise air travel (2001), the demise of old-timers such as Transbrasil, VASP and Varig (the latter was acquired by Gol in 2007) and TAM’s rapid emergence as Brazil’s flag carrier on long-haul international routes.

The late 2000s saw the rise of a new generation of LCCs. Webjet, launched in 2005, and older-established small carriers such as TRIP and BRA ramped up growth (BRA did not make it, ceasing operations in late 2007). Azul, David Neeleman’s well-funded start-up, took to the air with JetBlue-style E190/195 operations in December 2008. And in 2010 Synergy Group began in earnest to build up Avianca Brazil, a small operator previously known as Oceanair.

The decade witnessed the beginning of the rapid rise of Brazil’s new middle class, made up of many people who had not flown before. The “C class” has expanded as a result of healthy GDP growth, rising incomes and effective anti-poverty policies. Definitions are not always clear, but according to data presented in Azul’s IPO prospectus from IBGE (Brazil’s Institute of Geography and Statistics), between 2005 and 2010 nearly 40m Brazilians entered the middle class and an additional

The Brazilian market was ripe for air travel stimulation also because long-distance travel alternatives are limited. Brazil is geographically similar in size to the continental US, but it has no interstate rail system and the road infrastructure is poor. Buses have traditionally been the only low-cost option for long-distance travel, but that mode is extremely time-consuming. Tapping that segment with low fares was the cornerstone of Gol’s strategy from the start (and a key theme later adopted also by other Brazilian carriers).

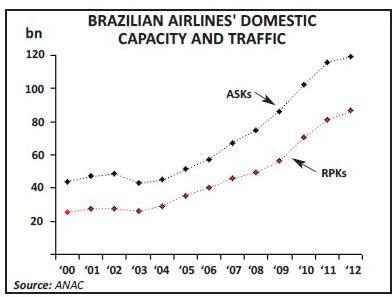

The growing middle-income segment, rising incomes and increasing availability of low air fares led to a surge in air travel. Domestic air passenger numbers in Brazil have increased from 28m in 2000 to over 92m in 2012, overtaking the bus passenger volumes in 2009. Growth was especially strong in the 2005-2010 period, when industry domestic RPKs doubled. 2010 and 2011 saw 24% and 16% RPK growth, respectively.

Not surprisingly, Brazil has struggled to cope with the sudden high air traffic volumes. Terrible ATC and infrastructure problems, exacerbated by two fatal accidents, reared their ugly head in the mid-2000s, setting the government on a course for infrastructure

Of course, a major part of the traffic boom especially in 2009-2011 was the result of significant capacity addition and intense fare wars, as Gol, TAM and the aggressive new-entrant LCCs battled for domestic market share. (In Brazil airlines are allowed to establish their own domestic fares without prior approval, though under 2010 regulations they are required to report their fares monthly to ANAC.)

In 2011, a combination of overcapacity, declining yields and a 30% hike in fuel costs led Gol and Tam to start losing money in domestic operations – a situation that has remained to this day. The airlines actually began to rein in capacity growth in late 2011, which led to a somewhat healthier pricing environment. But by then Brazil’s economic growth was stalling, which in combination with the higher fares led to reduced travel demand.

Brazil’s GDP growth stalled alarmingly in 2012 – just 0.9%, compared to the government’s forecast of 4.5% at the beginning of last year. This followed 2.7% growth in 2011, 7.5% growth in 2010 and a 0.3% dip in 2009 (the global recession year). Air travel demand (domestic RPK) growth in Brazil has also slowed dramatically: from 16% in 2011 to 6.8% in 2012 and into negative territory this year (down 1% in 1Q13 and down 3.4% in April).

So, Brazilian airlines now find themselves in a very different economic and demand environment. Over the past 12 months or so they have taken extensive remedial action, including capacity cuts. The key questions are: How long will the weak economic conditions last in Brazil? And have the airlines adjusted sufficiently to restore profitability in 2013?

Industry consolidation

The past couple of years have also seen a major industry consolidation phase in Brazil or involving Brazilian carriers. The biggest of the deals was LAN’s takeover of TAM, announced in August 2010 and completed in June 2012. TAM is now part of the powerful Latam Airlines Group, which dominates the Latin America region and could in the future capture market share from competitors in Brazil. On the other hand, the deal helped the overcapacity situation in Brazil. Latam has adopted very rational strategies for TAM Brazil, which it has kept as a separate business division.

Gol, having absorbed Varig in the late 2000s, took over Webjet, Brazil’s fourth largest carrier, in 2011. Since securing all the necessary regulatory approvals late last year, Gol has fully integrated the small low-cost carrier.

Azul, Brazil’s third largest airline, acquired regional carrier TRIP in May 2012. The two received their final antitrust approval in March and have been integrating under the Azul brand.

When the dust settles, the industry implications of these deals look likely to be as follows. First, there will obviously be fewer players in Brazil – something that should help the airlines cope better with the slower-growth period.

Second, the Azul-TRIP union has created what could soon be described as a “third force” in Brazilian aviation. It has weakened the TAM-Gol domestic duopoly, which had already declined steadily because of the rapid growth of Azul and other carriers but which still accounted for a combined 74.6% of domestic RPKs in April. Azul has described the TRIP acquisition as being equivalent to about four years of growth. The Azul-TRIP combine had 17.5% of the domestic market in April, and the share could be 20% or higher in full-year 2013, helped by Gol’s and TAM’s cutbacks.

Third, as a result of the consolidation, virtually all (99.3%) of Brazil’s domestic traffic is carried by four airlines. The “small LCC upstart/other carrier” segment, which contributed significantly to the price wars in recent years, has temporarily disappeared. Of course, in the longer term there are bound to be new entrants, especially when airport capacity constraints ease. (It is hard to picture there not being a “Virgin Brazil” eventually.)

Post-1Q12 recovery efforts

In early 2012 Brazil’s airlines were feeling the effects of multiple negative factors. In addition to the weaker domestic travel demand, fuel prices were high, labour costs had risen, airport charges had gone up by 150% in 2011, and the Brazilian real had depreciated against the US dollar (increasing the airlines’ dollar-denominated liabilities).

Gol, which also had serious balance sheet issues, began to take remedial action in March 2012 — scale back expansion, slash costs and raise capital. With the merger transaction completed, Latam’s new management followed Gol’s example in August 2012 and began to rein in TAM’s growth plans.

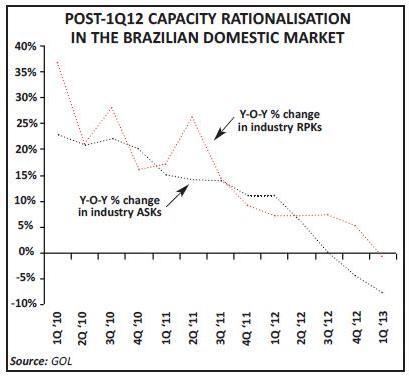

The result has been an unprecedented capacity discipline in Brazilian aviation. Gol’s domestic ASKs fell by 5.4% last year. The decision to dispose of Webjet’s fleet in December facilitated an even bigger reduction in this year’s first quarter: the combined Gol-Webjet ASKs were down by 15.7%. TAM’s domestic ASKs fell by 1% in 2012 and 9% in 1Q13. The airlines are now projecting domestic capacity declines of “up to 7%” (Gol) and 5-7% (TAM) in 2013.

The smaller carriers too are moderating their capacity growth. Last year Azul’s ASKs increased by 28%, but the combined Azul-TRIP capacity was up by only 11.2% in the first four months of this year. After almost doubling in size last year (up 82%), Avianca Brazil slowed its ASK growth to 30% in January-April.

The result was a remarkable 7.8% decline in domestic industry capacity in Brazil in this year’s first quarter. However, Webjet’s closure was a special factor in that period, and April saw a more modest 4.1% decline in industry capacity.

The capacity cuts have led to impressive load factor improvements. TAM, whose new Brazil strategy has emphasised yield management, has since the summer consistently seen monthly load factors running at least 10 points above the year-earlier levels. The pricing and yield environment has improved, restoring unit revenue growth. Gol has recorded 13 consecutive months of unit revenue growth and has seen double-digit PRASK and yield increases in recent months. Gol has also undertaken impressive cost cutting; its drastic measures have included a 20% workforce reduction over the past year.

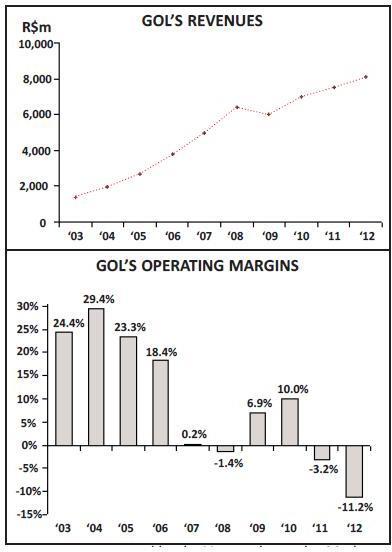

The downside has been the weak demand (the Brazilian market is highly price-sensitive). Also, Gol’s and TAM’s actions came too late to rescue last year’s financial results. Gol had a horrendous R$1.5bn ($750m) net loss in 2012, its second consecutive unprofitable year. Operating margin was a negative 11.2%, compared to 2011’s negative 3.2% and 2010’s positive 10%. TAM’s 2012 net loss was US$45.2m (on revenues of US$3.6bn); while more detailed results were not reported separately from Latam’s, it is known that TAM lost money in its domestic Brazil operations last year.

Azul disclosed in its preliminary IPO prospectus that it has had marginal operating profits but continued net losses in the past two years. Last year it earned a R$8.6m (US$4.3m) operating profit and a R$170.8m (US$85.4m) net loss on revenues of R$2.7bn (US$1.4bn). The operating margin was only 0.3%, down from 1.5% in 2011. In the past three years, Azul’s net losses have totalled R$373.9m (US$187m).

According to the prospectus, TRIP (which is now part of Azul) had operating losses of R$131.2m and R$99.4m in 2012 and 2011, respectively, on revenues of R$1.4bn (US$700m) and R$1.1bn. However, TRIP had a R$70.7m operating profit in 2010 (9.4% of revenues).

While Avianca Brazil does not formally disclose its financial results, according to local press reports, it has not yet attained profitability. Its revenues reportedly grew from US$575m in 2010 to US$1.35bn in 2012, making it about the same size as Azul before TRIP.

But all of the airlines are now anticipating positive results in 2013. Latam executives have made it clear in recent conference calls that they expect TAM to be profitable in Brazil this year. In late April Avianca Brazil executives were widely quoted saying that they expected 2013 to be the airline’s first profitable year. Gol, the only carrier to disclose specific targets, was in mid-May projecting a 1-3% operating margin in 2013.

Outlook: 2013 vs. longer-term

But the near-term outlook for Brazil’s airlines is not encouraging. Over the past 9-10 months GDP growth forecasts have been steadily revised down. The economy grew by only 1.9% in the first quarter. In early June S&P cut its outlook on Brazil to “negative”, noting that the country is seeing modest economic growth for a third consecutive year, with GDP currently projected to expand by only 2.5% in 2013. S&P also warned of a risk of a “more persistent slowdown in household spending” in Brazil. Despite the slow growth, inflation remains high at around 6%.

Brazil’s airlines continue to face significant cost pressures, in part because of unfavourable exchange rate developments. In May and early June the Brazilian real weakened further against the US dollar, continuing a trend that has been evident for some time. Since March the real/dollar exchange rate has moved from R$1.94 to around R$2.14 (up 10%).

All of this has dampened Brazilian carriers’ near-term profit prospects. 2.5% GDP growth represents the bottom end of the range that Gol’s 1-3% operating margin forwcast is based on. One analyst estimated that if the real/dollar exchange rate remained at R$2.13, Gol’s 2013 operating margin would be one percentage point lower (thus in the 0-2% range) and its 2013 net loss would increase from R$161m to R$387m.

Also, even though Gol and TAM seem committed to continued capacity discipline, it could fall apart. It is now low season in Brazil (the second quarter is historically the weakest) and there have been instances of aggressive fare discounting. The airlines have all adopted different revenue strategies. As some analysts have noted, it is a point of concern that Gol wants to maximise the yield and TAM seems to want to maximise the load factor. This has meant TAM gaining domestic market share – something that may not be acceptable to Gol.

But there are indications that the Brazilian airline industry is reaching a new level of maturity and wants to focus on sustainable growth. Last year the airlines got their act together to create their own association, ABEAR, which has taken on key industry issues such as airport costs and fuel taxes.

Of course, because of the burgeoning middles class, air travel in Brazil is expected to continue growing this year. ABEAR’s latest forecast projects 7% demand growth in 2013 (in line with the historical relationship of traffic growth exceeding GDP growth two or three times), down from an earlier forecast of 9%. Also, this year and in the medium-term, there will be the boost provided by the major international sports events hosted by Brazil – the FIFA Confederations Cup this summer (June 15-30), the World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016.

In the longer term, Brazil continues to be one of the most attractive aviation markets in the world because of its size and growth potential. Total (international and domestic) enplanements per capita are still relatively low — about 0.5, compared to the US’s 2.3. In 2010 Brazilians still boarded interstate buses 67m times instead of flying. According to Azul’s IPO documents (citing Business Monitor), Brazilian nominal GDP per capita, having risen from US$7,200 in 2007 to US$11,354 in 2012, is projected to reach US$20,564 by 2020. And an increasing share of the GDP is going to the middle or lower income classes.

In the Brazilian international markets, open skies ASAs with key world regions should help keep traffic growing at a robust rate. A Brazil-US open skies ASA is being implemented in stages and should be fully in force by 2015. A Brazil-EU open skies ASA is expected to come into force in 2014.

While Gol and TAM are well positioned for long-term growth in Brazil because of their many competitive advantages, including formidable slot holdings at the main airports, Azul and Avianca Brazil also have good prospects. First, the domestic market is so large that there is probably enough traffic for everyone. Second, the smaller carriers tend to focus on different segments or specific niches – something that will help them survive (though there is enough overlap to ensure competition). This is especially true with Azul, which focuses on regional routes and currently operates only E190/195s.

Third, the Brazilian government is determined to level the playing field a little, to ensure competition and low fares. Much of the attention has focused on Sao Paulo’s Congonhas, the busiest domestic airport in Brazil and currently the only one where slots are necessary. The airport, which cannot be expanded because it is bound by built-up areas of the city on all sides, is dominated by TAM and Gol (90% of the slots), but newcomers like Azul are keen to secure a foothold there.

After years of studies, SAC recently came up with proposals on redistributing slots at Congonhas and held public consultations earlier this year. BofA Merrill Lynch analysts estimated in February that Gol and TAM could lose perhaps 27 daily slots to the smaller carriers, which would see their slot share increase from 9% to 20%. But the exercise is fraught with difficulty. For example, a slot transfer to Azul would have the undesirable effect of reducing total seats offered at the capacity-constrained airport, because Azul operates smaller aircraft. The government may be hesitant to hurt TAM and Gol when they are losing money or to rock the boat too much just before Brazil hosts a series of major international sports events. Nevertheless, SAC now intends to release the findings of the public hearings by the end of June and to come up with slot distribution rules this year that can be applied to any airport that reaches saturation.

As an interesting twist, in late May DECEA (Department of Airspace Control) submitted a study commissioned by SAC suggesting that Congonhas has room for 25% expansion. All that the government would need to do would be to reverse restrictions imposed after a 2007 fatal crash and to ban non-commercial flights at the airport. The study reportedly argues that Congonhas could safely handle 38 movements per hour, four more than currently, and that its annual passenger handling capacity could rise from 16.7m to 20.7m.

Separately, the Brazilian government is concerned about the airlines’ continued financial losses. In early April SAC asked ANAC and BNDES (the state-owned bank) to carry out studies on the financial health of Brazil’s airlines and to suggest ways to help the industry. The results of those studies are not yet known. There are also moves in Congress to try to ease the airlines’ fuel tax burden.

In recent months Brazil’s airlines have been campaigning through ABEAR for reductions in VAT rates on jet fuel. In Brazil VAT (“ICMS” tax) is set and collected at state level and varies greatly by state and by product (7%-25%). In April the state of Brasilia reduced its VAT rate on jet fuel from 25% to 12%, the same as in Rio de Janeiro. The airlines now want the state of Sao Paulo to also reduce its VAT rate on fuel from 25% to 12%. This would have material positive impact on most airlines’ finances, because SP is the country’s most important hub and a large part of the fleet is refuelled there. ABEAR’s longer-term goal is to equalise the VAT at 12% throughout Brazil.

On the foreign ownership front, Azul suggested in its IPO documents that there was a “significant possibility” that the Brazilian Aeronautical Code could be amended in 2013 or 2014 to permit foreign investors to hold up to 49% of the voting shares of Brazilian carriers (compared to a maximum of 20% at present). The issue has been under discussion since 2009 and there is a draft bill making its way through the Brazilian House of Representatives. In the short term the impact would be minimal, because under the existing rules Brazil’s airlines can issue preferred shares to raise more equity from foreigners. But in the longer term it would obviously make it more attractive for foreign investors to help launch new airlines in Brazil.

Infrastructure provision

The biggest single factor that could limit Brazil’s airlines is inadequate airport infrastructure. A particularly damning assessment of the situation came in late May in a presentation from CADE. A senior executive from the agency reportedly argued that without major investments in the next two years, competition at the country’s eight largest airports will be “near-impossible”. Sao Paulo’s Congonhas and Rio’s Santos Dumont (the two main domestic airports, both operated by INFRAERO) are already effectively closed to new entrants, but growth in air travel in the next two years will mean that six other airports too will not be able to accommodate new entrants or additional air service. Those airports are Belo Horizonte’s Confins, Brasilia, Campinas, Curitiba and the international airports in Sao Paulo and Rio (Guarulhos and Galeao).

Fortunately, three of those six airports (Guarulhos, Campinas and Brasilia) were handed over to private consortia on 20-30 year concessions in 2012, and another two airports (Confins and Galeao) are due to be privatised this autumn, leaving only Curitiba under INFRAERO’s management. Substantial and timely capital investments to expand the airports and improve their facilities were a key condition in the transactions. The three airports privatised in 2012, which handle some 30% of the country’s passengers, will get a combined minimum investment of R$18.1bn (US$9.1bn), of which R$2.9bn (US$1.4bn) must be in time for the World Cup. Each of those airports will get a new terminal, as well as expanded runways, aprons and parking areas.

Under the preliminary terms released for this year’s privatisations, Galeao will get a R$5.2bn investment over 25 years, to facilitate its growth from the current 17.5m passengers a year to a projected 60m by 2038. Confins will get a R$3.5bn investment over 30 years, to take it from its current 10.4m passengers a year to 43m by 2043.

The government pocketed R$24.5bn from the first three privatisations and has said that it will use part of the funds to improve airport infrastructure across the country. According to Azul, of the 67 Brazilian airports managed directly or indirectly by INFRAERO, some 13 airports are currently receiving infrastructure investments and upgrades. This year INFRAERO is boosting its own airport investments by 40% to R$2.8bn.

Starting in 2014, much of the revenue collected from the large privatised hubs will be invested in regional airports. It will be part of a comprehensive package of incentives for the regional aviation industry that the government announced in December 2012. The package includes investments of up to R$7.3bn in regional aviation infrastructure, expanding the number of commercial airports from 129 to 270 in the next ten years, and subsidies and airport fee exemptions for regional flights.

There has been much speculation about whether all the facilities currently under construction will be ready for the World Cup. But some important benefits are already evident. The new expansion projects at Sao Paulo’s Campinas since its privatisation in February 2012, which include R$1.4bn worth of investments by 2014 and a new runway by 2017, have already created attractive potential growth opportunities for Gol and TAM. Gol recently filed with ANAC to begin six new daily flights from Campinas, which would double its operations at the airport; the goal is to attract new traffic from the Campinas area, rather than divert traffic from Sao Paulo. TAM is reportedly also studying expansion at Campinas.

It seems that Brazil is at long last fully committed to ensuring adequate airport capacity and facilities. Improving airport infrastructure is a major focus of the “Growth Acceleration Program” launched by President Dilma Rousseff’s government. INFRAERO expects Brazil’s annual passenger traffic (domestic and international) to more than double between 2014 and 2030, from 146m to 310m passengers.

Gol: Recovery in 2013?

Gol has staged quite an impressive restructuring in the past year, much like it did in 2009-2010 following the Varig acquisition, which many considered a strategic mistake. This time, though, the top management has changed. In June 2012 founder Constantino de Oliveira Jr. stepped down as CEO, and Paulo Kakinoff, formerly Audi’s Brazil head and a Gol board director, took over. The idea was to have a truly experienced industry executive steer Gol back to profitability.

Despite the sharp reduction in ASKs and many cost headwinds, Gol managed to keep its ex-fuel unit costs flat in the first quarter. This feat was attributed mainly to a 20% headcount reduction. Analysts say that there is still room for improvement on the cost front.

Despite the contraction, Gol’s revenues declined by only 4% in 1Q. The load factor improvement was much smaller than competitors’, but the low-70s load factors are adequate and Gol is outperforming its peers in yield and RASK.

The main benefit of the R$70m Webjet acquisition was that it strengthened Gol’s slot holdings at six key airports: Guarulhos, Brasilia, Galeao, Santos Dumont, Confins and Porto Alegre’s Salgado Filho. It was also a defensive move. And the acquisition helped in the rationalisation efforts, because Gol opted to end Webjet’s operations and dispose of its 20 “uneconomic” 737-300s. It seems to have been a relatively quick and successful integration. Brazil’s antitrust regulator CADE made it a condition that the Gol-Webjet combine meet certain performance standards – namely that they operate from Santos Dumont with “85% efficiency” (a measure of the frequency a slot is used, on-time performance and load factor).

Earlier this year Gol implemented what it described as a “new route network” – a collection of changes and strategy refinements to coincide with the merger of the Gol and Webjet networks. Gol has eliminated some routes, reduced night flights, strengthened Guarulhos hub operations, improved connectivity with partners (especially at GRU) and increased focus on the corporate market. As of late February, the Gol-Webjet network covered 51 domestic and 14 international destinations.

Gol is currently keen to expand internationally, to diversify revenue sources (given the sluggish demand in Brazil) and to gain a natural exchange rate hedge. It is indicative that while cutting capacity domestically this year, in January-April Gol’s and TAM’s combined international capacity was up by 15.6%.

Notably, in December 2012 Gol entered the Brazil-US market with daily Sao Paulo-Orlando and Rio-Miami flights, which are operated via Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) because the 737-800s need a fuel stop. The flights are timed to arrive in Santo Domingo at about the same time, allowing passengers to switch. In 2007 Gol briefly tried to maintain Varig’s Brazil-US 767 fights but the services were not viable.

Gol has good reasons to be in the Brazil-US market. As the management explained recently, the idea is to exploit what has been a high-growth market, offer customers more options and “reroute domestic capacity to the international market”. But Gol faces many challenges in those operations. It has less of a cost advantage on long haul and international routes, the US operations are more expensive and the one-stop economics are questionable. TAM and American have nonstop flights in those markets and offer more frequencies and a better product, so Gol has to discount very aggressively. TAM will also soon be able to connect to American’s huge domestic network at Miami, where Gol’s partner Delta does not have much of a presence. Gol’s daytime flights do not even connect effectively with its own vast network in Brazil. Santo Domingo does not have much of a local market, certainly less than Caracas, which was Gol’s original choice for the intermediate stop (before those plans were scuppered by the Venezuelan authorities).

But Gol executives called the first five months’ results in the US operations “encouraging” and noted that load factors were in the mid-80s. Gol is sticking to its plans to build a hub in the Dominican Republic and has already presented its expansion plans to the DR government, which were “very positively received”.

In late May Gol announced another unusual-sounding expansion idea: scheduled flights to Africa. The airline is studying the possibility of adding a Recife-Lagos route, which it would be able to operate with 737-800s. It would be Gol’s first long-haul intercontinental route. At first glance this would seem like a totally unnecessary diversion from the “back to basics” strategy of being an LCC, but Gol has already diverted from that model with the US and DR operations. It could be another useful way to diversify. Brazil and Nigeria have strong ties and there is longstanding demand from businesses for direct air links, which could prove lucrative.

Gol has also continued to add new intra-Latin America international service. Last year it benefited from the demise of two small carriers, Uruguay’s Pluna and Bolivia’s Aerosur, which gave it the opportunity to serve Montevideo and San Cruz from Sao Paulo. Gol is only interested in markets that can be operated with 737s and is looking to grow its international operations to eventually account for 15-16% of its total capacity, compared to 8% at present.

This year Gol is also building its codeshares with Delta, which in December 2011 paid $100m for a 3% stake in Gol, also securing a board seat, an exclusive codeshare agreement in the Brazil-US market and two 767s. From September all of Delta’s services to Brazil will be connected to Gol’s network and sales channels. Otherwise, Gol has an “open architecture” type alliance strategy similar to JetBlue’s and WestJet’s and is not interested in entering into a global alliance.

Gol does not have any liquidity issues, because it has made it a policy to maintain strong cash reserves ever since it narrowly escaped the post-Varig cash crunch. Including the R$1.1bn ($550m) proceeds from the late-April IPO of its Smiles FFP unit and another R$400m ($200m) of proceeds from a separate mileage sale, Gol will have around R$3.1bn ($1.6bn) in cash at the end of June – a very healthy 39% of lagging 12-month revenues and roughly the same amount it has in debt obligations.

Gol remains highly leveraged, though, with adjusted gross debt (including leases) of R$9.7bn ($4.9bn) at year-end 2012. But since there are no major repayments due in 2013-2014, Gol merely intends to “prepay what is reasonable” and due in the short term while keeping a strong cash position. The airline hopes that growth in EBITDAR will reduce its debt ratios to satisfactory levels.

The management feels that the fleet plan has been trimmed to what is needed in the next few years. Gol is taking 16 new aircraft in 2013, some on sale-leasebacks. In October 2012 Gol ordered 60 737 MAXs, for delivery from 2018. The $6bn order did not go down well with analysts, given Gol’s losses, but the aircraft will be mainly for replacement and will ensure competitive costs in the long term.

It seems likely that Gol’s losses bottomed out in the fourth quarter, when the EBIT loss margin sank to a dismal -16.9%. The March quarter saw a promising 4.9% positive operating margin. If the economy and exchange rates cooperate, Gol has a chance to roughly break even operationally in 2013. However, a net loss is expected for a third consecutive year.

TAM: The new Brazil strategy

The Brazilian market is very important to Latam because it accounts for 30% of the group’s revenues. Brazil was also one of the key areas where Latam hoped to grow and obtain early merger synergies (the other was cargo), so it became an immediate focus after the merger closed. However, turning around the Brazil passenger operations has been Latam’s biggest challenge.

Among the first integration moves, Latam strengthened its intra-Brazil cargo operations by blending LAN subsidiary ABSA Cargo’s Brazil operations and two 767-300Fs into TAM Cargo and investing in cargo infrastructure in Brazil. In turn, TAM Cargo’s international operations were blended into LAN Cargo’s international operations. As a result, Latam is now a stronger cargo force in Brazil and internationally, better able to capitalise on growth opportunities when the cargo sector recovers.

On the passenger side, Latam’s TAM Brazil unit has followed Gol’s example and sharply cut capacity in the domestic market. But TAM follows a different strategy from Gol in that it is trying to boost revenues through higher load factors and better yield management. Like Gol, it is striving to cut costs and improve efficiency. As a result, TAM’s load factors have risen to around 80% from the 65-70% historical range and recent months have seen low double-digit PRASK growth.

But it is hard to assess the financial success of that strategy because Latam no longer discloses yield, cost and operating margin information for TAM. In a February 19 report, JP Morgan analysts said that they believed the Brazil domestic operations were still unprofitable — that most of TAM’s PRASK improvement has been driven by ASK reductions, rather than passenger revenue improvement.

In recent conference calls, Latam’s management has merely stated that TAM Brazil has made significant progress in its turnaround and seen sequential improvement. The executives have said that they remain convinced that capacity discipline and adequate market segmentation are the key. The strategy makes sense when considering that TAM has always been a full-service carrier, trying to cater for all segments. And it obviously has benefited from LAN’s expertise in market segmentation.

It would seem that much work remains to be done on the cost front. According to Latam’s 2012 annual report, the group is exploring opportunities to apply aspects of the low-cost model that LAN has utilised in other Latin American countries to TAM’s domestic operations in Brazil.

LAN launched its version of the low-cost business model in 2007 to increase the efficiency of its domestic operations in Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and to some extent Argentina. The model features higher aircraft utilisation through more point-to-point services, more night flights and faster turnarounds; use of a standardised fleet of A320-family aircraft; lower sales and distribution costs through higher internet bookings, reduced agency commissions and increased self check-in; and simplification in back-office and support functions. Some of the cost savings are passed to consumers through fare reductions, which has stimulated traffic and enhanced profitability.

There is obviously nothing unique about this model – just a collection of the best and perhaps easiest-to-apply components of the standard LCC business model – but it has worked well for LAN in the Spanish-speaking domestic markets, as indicated by Latam’s continued rapid capacity addition in those countries. If the model can be applied to TAM Brazil, Gol better watch out.

Of course, in addition to its 42-point network in Brazil (as of February 28), Latam has international operations out of Sao Paulo and Rio. From Brazil it operates to eight other Latin American countries, as well as the US, France, Germany, the UK and Italy. The management has reportedly said that one of their dreams is to turn Sao Paulo into a major international hub.

Last year, as Brazil’s domestic growth slowed, Europe stagnated and TAM was expecting four new 777-300ERs, Latam expanded significantly in the Brazil-US market. Among other things, TAM added a Rio-Orlando route and boosted seats on Sao Paulo-Miami by upgauging from A330s to 777s. This strategy backfired when competitors grew just as recklessly, leading to excess capacity and heavy discounting. Latam has seen sharp falls in its international load factor and RASK in the past two quarters, which was largely attributed to the long haul routes from Brazil.

As a result, Latam is now scaling down international expansion from Brazil. It has terminated the Rio-Orlando route and in August will pull out of the Rio-Paris and Rio-Frankfurt markets (opting to route those passengers via Sao Paulo).

Latam feels that the US growth was justified because most of the routes are strategic and will be profitable in the long run. The performance of the long haul network from Brazil is expected to improve in the second half of this year, in part because of the remedial actions and because of the planned TAM-American codeshares.

Latam announced its long-awaited global alliance decision on March 7, opting to remain in oneworld and for TAM to leave Star and join oneworld (expected in 2Q14). Although there are likely to be negative implications for the combine’s Brazil-Europe business, the decision was a major positive for the group’s Brazil-US operations. The US is the number one international destination for Brazilians. American is the largest carrier on those routes and operates a major hub in Miami, the key destination for Brazilians. T AM will benefit enormously from the codeshares with American (which secured final regulatory approvals in May), because it will get significant feed from American’s domestic network through Miami and New York. Star may be a bigger global alliance, but it has not helped TAM penetrate the US market, because United does not have a hub in Miami.

Latam is only just getting started in the process of realising the projected $600-700m annual merger synergies (not expected in full until June 2016), so there is much scope for financial improvement in many areas, including Brazil. While LAN’s and TAM’s fleet plans have already been rationalised as a result of the merger, Latam is in the process of further adjusting the fleet plan to match the weaker demand trends in Brazil.

TAM’s financial results and balance sheet have already benefited from the merger in various ways. All hedging and new aircraft financing are done at the consolidated level, and TAM’s aircraft and related debt are likely to be moved to the Latam balance sheet, which has the US dollar as its functional currency. This reduces earnings volatility caused by external factors such as foreign exchange. Even with the loss of Latam’s investment-grade credit rating (the biggest negative in the merger), TAM’s aircraft financing costs have been reduced. Latam is working to recover the investment-grade ratings, though it could take a couple of years. Following approval from shareholders in early June, the company is planning a $1bn equity offering in the second half of 2013.

Azul-Trip: the

emerging “third force”

Azul was uniquely well-funded when it began operations in December 2008, having attracted US$200m in capital from US and Brazilian investors. It has also grown extremely rapidly, achieving $1bn revenues in its third year (2011) and capturing a 13.4% domestic market share in April – or 17.5% when its Webjet acquisition is included. Even though it has only attained marginal profitability (and only on an operating basis), the story is compelling enough for an IPO. Azul filed plans on May 24 to list preferred shares in Brazil and the US in offerings that could raise up to R$1.1bn (US$550m) mainly for fleet expansion.

Azul has been able to grow so rapidly, first, because it has developed a new hub at Viracopos Airport in the city of Campinas, about 70 miles from Sao Paulo. Second, Azul has avoided too much overlap with Gol and TAM, because it focuses on regional markets and operates smaller aircraft (E190/195s and ATR72s).

Third, Azul has been well-received by Brazil’s travelling public. Its low fares, nonstop flights that bypass hubs and reduce travel time, superior JetBlue-style offerings (leather seats, more legroom, free LiveTV at every seat) and its customer-focus and fresh approach have gone down well in the marketplace. Like JetBlue, its has built a strong brand.

According to the preliminary IPO prospectus, Azul’s model is to stimulate demand by providing frequent and affordable air service to underserved markets throughout Brazil. Because it operates smaller aircraft, it can serve cities the larger competitors cannot. These attributes have enabled it to attract both business traffic and cost-conscious leisure travellers, build the largest airline network in Brazil in terms of destinations (103 – roughly the same as Gol and TAM combined in Brazil) and dominate the markets where it is present. Azul is the only airline on 70.7% of its routes and the frequency-leader on another 10.1% of its routes.

The leading network position has enabled Azul to achieve significantly higher unit revenues than the other domestic carriers. The PRASK premium, load factors consistently around the 80% mark, high efficiency and a competitive cost structure offset the poorer economics of smaller aircraft. Azul also gives credit to its “proprietary yield management system” for maximising revenue generation.

Brazil may be an especially suitable market for this type of business model, because it has a large number of medium-sized cities scattered around the huge country that have much economic power, and hence travel demand, but cannot support regular operations with 150-seat aircraft. Azul has tapped opportunities in such underserved regional markets, many of which had considerable pent-up demand and have continued to see double-digit growth even as Brazil’s GDP growth has slowed.

Azul seems intent on focusing on such markets at least for the medium term, first, because in 2010 it ordered up to 40 ATR 72-600s. The 70-seat aircraft enable it to add regional routes that are too small even for its 106-seat E190s and 118-seat E195s. Second, there was the May 2012 acquisition of regional carrier TRIP.

The all-stock merger with TRIP offered cost savings and major revenue benefits through the expanded network. The two airlines had uniform fleets, similar strategies and little overlap. TRIP brought 46 additional cities, strategic slots at Guarulhos and Santo Dumont, a leading position in Belo Horizonte (Brazil’s third largest metro area) and substantially improved network connectivity all around. Azul and TRIP have codeshared since December, received final antitrust approval from CADE in March, have fully integrated all administration and back-office functions and expect to receive a single operating certificate from ANAC by July.

At the end of March, Azul and TRIP had a combined operating fleet of 118 aircraft – 41 E-195s, 22 E-190s, five E-175s, 39 ATR 72s and 11 ATR 42s. Firm order commitments totalled R$2.4bn – 23 E-jets and 20 ATR 72s, for delivery in 2013-2016.

Since Azul-TRIP will continue growing in 2013, albeit at a somewhat slower rate, while Gol and TAM contract, the combine could have 20% or more of the domestic market by the end of this year. Azul is keen to gain better access to Sao Paulo’s centrally-located Congonhas Airport, and it could be a major beneficiary if the slot redistribution takes place. Longer-term progress will depend on the infrastructure being there at the mid-sized cities to facilitate growth, though the government seems to be making regional air services and infrastructure a priority and Azul does not anticipate any problems.

The interesting question now is how soon Azul-TRIP will order a third, larger aircraft type and/or venture into the intra-South America international markets. Neeleman indicated last year that the fleet plans were set through 2015 but that after that the airline could consider other aircraft types.

The IPO will enable key investors such as the US private equity firm TPG, which bought a 10% stake in Azul in January 2010, to exit, if they so choose. But Neeleman, who currently holds 67% of Azul’s stock and voting rights, will remain firmly in control. He will continue to control all shareholder decisions, including the ability to appoint the majority of the board of directors. Neeleman, who was also JetBlue’s visionary founder, has indicated in several interviews in recent years that he did not like the way he was ousted from the New York-based carrier by its board of directors after one fateful snowstorm in early 2007.

Avianca Brazil:

Future link with TAP?

While industry consolidation has left Avianca Brazil in a more distant fourth place in the domestic market, this airline too has potential to be a major player in Brazil. First, it has grown extremely rapidly in the past couple of years, to account for 7.1% of the domestic market in April. Second, when TAM leaves Star, Avianca Brazil could play a key role in ensuring other Star members access to Brazil. Third, Avianca Brazil is a potential future bidder (or a partner) for Portugal’s TAP.

Compared to Azul’s impeccable pedigree, Avianca Brazil’s background is more colourful. Established in 1998 as an air taxi company, Oceanair began scheduled services in 2002. Brazil’s Synergy Group acquired it in 2004 and grew it rapidly in the wake of Varig’s contraction in late 2007, even taking it to international markets with 767-600s. That was a mistake and led to a sharp contraction in 2008. Oceanair ended international flights and shed its 737s, 757s and 767s, leaving only a fleet of 14 Fokker 100s. There was no growth in 2008-2009.

In early 2010 Oceanair was rebranded as Avianca Brazil (its 100%-owners also hold a controlling 60% stake in AviancaTaca Holdings). The airline resumed expansion with the help of A318s leased from GECAS and with A319s and A320s that came from its sister company. Its fleet has grown from 14 aircraft at year-end 2009 to 32 at present.

The business model is slightly unusual and not proven. Avianca Brazil is very up-market, offering full service even on the shortest hauls. It operates single-class but offers the most generous domestic economy seat pitch, superior in-fight entertainment and free meals. It has won many “best airline” type awards. It achieves extremely high load factors — usually around the 80% mark; in March the load factor was 82.2%, 11 points above the industry average. In other words, by offering a better product at the same price as competitors, Avianca Brazil captures more traffic, which it claims covers the higher costs.

Avianca Brazil benefits from extensive slot holdings at key airports. This has enabled it to build a 24-point network focusing on trunk routes. It has a large operation at Sao Paulo’s Guarulhos airport (its main base) and it operates on the lucrative Rio de Janeiro-Sao Paulo shuttle route, offering 10 or so daily flights in each direction.

Since profitability has been elusive, the management is trying to rein in growth in the short term. Or, as Synergy’s owner German Efromovich recently put it, the airline has a plan of “orderly and sustained” growth. Avianca Brazil is committed to taking five A318s in 2013 – the last batch of the 15 aircraft coming from GECAS. But there is much flexibility with the Fokker 100 retirement schedule, which is now being accelerated to keep the fleet size roughly flat (though there will still be 30%-plus ASK growth as the A318s replace the smaller aircraft).

Should it become desirable to boost the growth rate – say, if Gol’s and TAM’s cutbacks lead to attractive market opportunities – Avianca Brazil could also receive more A320s from its sister company. Synergy and AviancaTaca have a strong A320 orderbook, so Avianca Brazil need never be short of aircraft.

In the longer-term Avianca Brazil is likely to reintroduce international services. It is not part of the recently-launched AviancaTaca single brand, but it is considering joining the FFP and at some future point is likely to be integrated into that group. But even before that happens, Avianca Brazil is expected to join the Star alliance and fulfil an important role as possibly the only Star member in Brazil. Because of its presence at Brazil’s main airports, it is well placed to connect to other Star carriers.

There is also the intriguing possibility that Avianca Brazil could secure TAP as a sister company – or even be a bidder for TAP — when the Portuguese carrier’s privatisation process restarts, which could be this autumn. TAP’s extensive service to Brazil would be a great match with Avianca Brazil’s domestic network.

| % of total domestic RPKs | ||

| April 2013 | April 2012 | |

| TAM | 38.4% | 39.9% |

| GOL | 36.2% | 34.8% |

| Webjet | 0.0% | 5.3% |

| GOL+Webjet | 36.2% | 40.1% |

| Azul | 13.4% | 9.9% |

| TRIP | 4.1% | 4.3% |

| Azul+TRIP | 17.5% | 14.2% |

| Avianca Brazil | 7.1% | 5.0% |

| Others | 0.7% | 0.8% |

| TOTAL | 100% | 100% |