British Airways/Iberia: Quest for synergies

June 2010

BA + IB = IAG + ?

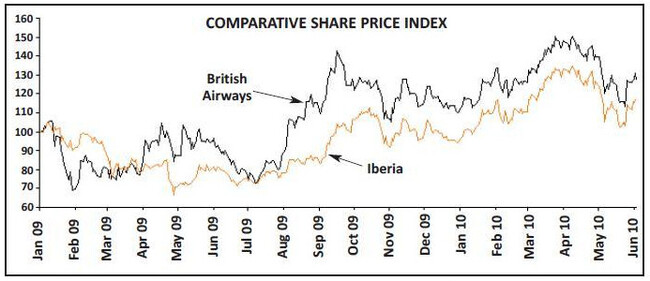

Last month British Airways held its annual Investor Day – unusually at the same time as publishing its annual results. With memories of volcanic ash hanging in the atmosphere over Heathrow and under the cloud of industrial action by one of the cabin crew unions the announcement that the company had achieved a slightly better than expected net loss of only £425m for the year to March 2010 (against a net loss of £358m in the previous year) may have been relatively good news. The main focus of the day however was on the two strategic developments that BA hopes to effect this year to put it once again in a comparatively competitive position with long term rivals Air France–KLM and Lufthansa: the planned merger with Iberia; and the likelihood of finally achieving Anti Trust Immunity (ATI) with long term partner American on the Atlantic.In December’s issue of Aviation Strategy we highlighted the strategic and organisational elements of the proposed merger. Following the formal signing of the agreement between the two in April, little has changed from our exposition then, save that the two have decided on the name of “International Airlines Group” as the controlling entity (slightly more imaginative than the original TopCo). Having been leapfrogged by its main competitors' strategic moves in recent years, this deal will put the combined group in position as the fifth largest global airline group by revenues – albeit still some two thirds the size of Air France–KLM or Lufthansa and a little way behind the new United and Continental combine and Delta after its absorption of Northwest. The two networks are basically complementary: BA’s strength on the North Atlantic, being based at the prime European gateway to North America at Heathrow; Iberia’s strength in the Latin markets in South and Central America with flows over Madrid Barajas.

The company made the usual expected statements, reiterating its comments made at the end of last year; the deal would

- give them a strong strategic position in the global airline sector

- provide complementary networks and hubs

- provide enhanced customer benefits

- maintain existing leading brands

- generate significant synergy savings (estimated at €400m annually by the fifth year – an estimate unchanged in the past six months)

Synergies

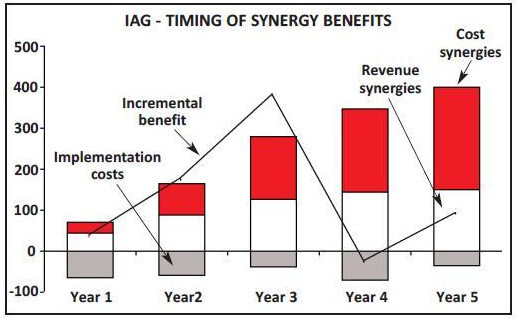

- encompass effective governance and management In the two years of negotiations the two have had a little more time than usual to work out the potential synergistic benefits of the merger – and have at least had the opportunity to benchmark their operations against the results particularly, presumably, of the Air France–KLM merger in 2003. They estimate that by the end of five years they should be able to generate an annual run–rate of benefits approaching €400m – or 2% of revenues – incremental to that already achieved through the long standing UKSpain JV and $1 $2 alliance coordination. Of this total around one third, €150m (less than 1% of combined revenues), would come from revenue enhancements, and of this 78% from passenger revenue improvements; the remainder from cost savings.

Is this realistic? In comparison with the gains achieved by Air France and KLM the revenue estimates may appear conservative – their revenue synergies are currently possibly running at over 3.5% of combined revenues, some 50% higher than their own estimates at the time of the merger. Despite this, Air France/KLM’s operating loss for 2009/10 was €1.3bn, a -6.1% margin on revenue, compared to British Airways’ -2.9%.

No doubt in the analysis of synergy calculations BA and Iberia (or their consultants) relied heavily on the benefits of examples of multiple hub operations in Europe at AF–KL through CDG and Amsterdam, or the slightly less visible example of Lufthansa/SWISS through Frankfurt, Munich and Zurich: the ability to redirect traffic, coordinate schedules to widen market attractiveness, and offer joint fare structures (what used to be known as interlining?).

There is one major difference of course – both KLM and Air France relied heavily on their hub operations and were competing aggressively for the same transfer traffic; their hubs being only 400km apart. Air France had used the capacity available through the four runways at Roissy CDG to grow into the cost savings it needed a decade ago through developing a strong wave system in order to create an attractive transfer hub to add to its relatively strong O&D markets into and out of Paris (being the only other destination in Europe after London with a good sized catchment area to generate good levels of point–to–point demand). KLM in contrast, lacking the strength of good point–to–point demand into and out of Amsterdam had grown through the regulated era from creating and relying on the network transfer capability provided through sixth freedom operations.

In contrast British Airways is based at a severely constrained airport. It does have the advantage of being at the best O&D market in Europe – and the principal European gateway to North America — and has spent the last decade concentrating more on the higher yielding point–to–point demand and premium transfer traffic while de–emphasising Economy transfers; although there is a significant amount of transfer traffic through Heathrow, and the company can switch its sales focus relatively easily — as it has done in the last two years (helped importantly by its move into the new Terminal 5).

Iberia also had a relatively constrained airport until the opening of the two new runways and fourth terminal in 2006; and while concentrating on its natural “niche” into the Latin American markets (with relatively strong point to point demand) has only since then really been able to develop Barajas as a transfer hub. There is also very little overlap in the respective route networks: of the 100 long haul destinations served in 2009 they only have twelve (or 12%) in common. This compares with a 33% duplication for Air France and KLM in 2003 of their then 102 long haul destinations (and a near 60% duplication on Asia/Pacific routes); intriguingly, by 2009, Air France and KLM had rationalised their offerings by hub so that this overlap had been reduced to nearer 24% overall (and 35% on the Far East).

So perhaps this consolidation move is unusual in Europe – it may be that it bring together more opportunities for access into new markets for each carrier than the competition that it removes; although there are natural reasons for the existence of the relative lack of destination overlap – consider the world map had the 1588 Spanish attempt to topple an undesirable heretical regime succeeded. For BA in particular – now with the likelihood of any further runway capacity expansion scotched at Heathrow for the foreseeable future (even though there may now be increasing pressure to move to mixed–mode runway usage to get some increase in capacity of the two runways) – there may be some rationale in expecting that Madrid could provide long run growth potential; one of the corollaries following on from the long term constraints at Heathrow may well be an increasing and perhaps accelerating shift away from short haul European operations and a gradual dismantling of the hub system.

The main passenger revenue benefits are expected to come from:

- Combining point of sale strength Apart from the natural positions in their home markets, British Airways' strengths lie particularly in North America and Iberia’s in Latin America. Combining sales activities in either region is expected to generate enhanced market access. Where neither are strong (such as France and Germany) it may be possible, as they claim, to create a credible alternative to the home carrier.

- Cross-selling to each other's customer base As distribution moves increasingly to own–site on–line internet booking the ability and incentive to present the other’s schedules should be incrementally beneficial. At the same time the ability to combine corporate accounts and account management should help redirect new forms of “captive” demand.

- Increased connectivity and optimised scheduling The alignment of schedules to optimise spread of flight timings naturally should increase attraction of demand flows. At the same time there may be opportunities to use the double hub to improve customer choice and flexibility – an example given was that there could be a mere 2% difference in trip timing for a flight from Rome to New York via Madrid compared with one through London (even though the premium passenger would probably want to fly direct — perhaps even on American?).

- Best practice in revenue management and selling processes Undoubtably the group will aim to move the revenue and capacity management systems to a core group back office function – the integration of IT systems will no doubt take time – and there should be some reasonable opportunities to align pricing, inventory management, revenue integrity, corporate and agency dealings and direct channels.

- Enhanced FFP proposition The combined 10m membership of BA’s Executive Club and Iberia’s Iberia Plus frequent flyer plans fall well short of the those of either Air France–KLM’s 13m Flying Blue or Lufthansa’s 15m Miles & More members – although there are a further 11m signed up to BA’s UK–based Airmiles programme. As the FFPs move increasingly towards ancillary revenue generation programme membership size becomes increasingly important. In addition the attractiveness to the members should increase as the earn–and burn potential on either carrier becomes more transparent.

By far the lion’s share of anticipated synergy benefits come from cost savings – but as usual it may be that they will take longer to achieve (and cost more to implement) than the anticipated revenue benefits. The group expects that almost a third (€70m) will come from IT integration: joint procurement of hardware and maintenance; elimination of duplication of infrastructure and development projects; move to common business processes and single best applications for key functions; and reduction of IT overhead through common IT strategy, simplification of processes and administrative tasks.

This may be somewhat more advanced thinking than that approached by AF–KL in 2004 (when both were concentrating on their independent post 2001 cost savings programmes) – but also probably one of the more difficult to implement well. The next largest element is expected to come from maintenance. There is at least some element of fleet commonality and there should be the opportunity for joint inventory control giving significant reductions in working capital requirements. At the same time benefits are expected to accrue from the sharing of best practices; coordination of engineering, planning and control better to absorb fixed costs; joint procurement of materials and components; and optimisation of common capabilities. A new group corporate centre is planned in order to take on the duplicated common back office functions – such as finance and commercial activities. Increase in size usually brings improvement in supplier bargaining power and the two expect to generate some €28m from savings in data and distribution costs, flight related costs such as on–board services, catering, HOTAC expenses; fuel purchasing at joint stations; aircraft insurance costs. Other costs synergies are anticipated from the integration of operations at common out stations – particularly sales and call centres, ground handling and ground operations, CIP lounges (what they have not yet done under $1 $2?) — as well as coordination of cargo operations, handling and trucking contracts. Longer term there could be significant benefits from fleet acquisition and combination of the fleet renewal plans.

ATI+BA+IB+AA=?

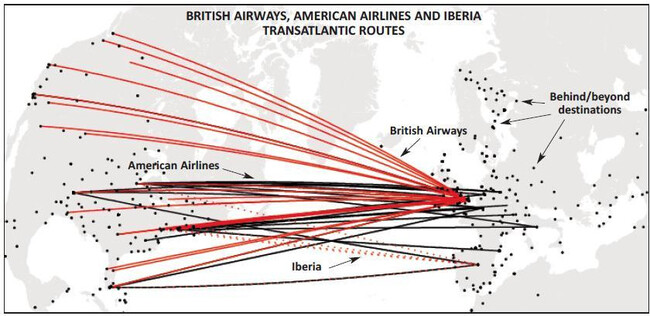

The merger agreement may have been signed but there is still quite some time before it is delivered. BA has to come to an agreement with its pension trustees over the deficit – with a deadline for the end of June – and Iberia still has an option to withdraw (on the basis of the pension) until the end of September. The regulatory approval process is likely to continue to the end of September, and on the basis that Brussels will not impose unbearable restrictions (and so far the only deal that the EU has meaningfully blocked was Ryanair’s attempted acquisition of Aer Lingus) shareholders' meetings to approve the merger are anticipated for November with a planned completion date in December. This deal has been long in gestation – some at British Airways have been working on it for the past eighteen years – but by the emergence of 2011 the new International Airlines Group SA should be a reality. It is ever a danger signal for a company, let alone an airline, to change its corporate name – witness United’s attempt to emerge as Allegis in the 1980s or Swissair’s attempt to reinvent itself as SAirGoup – but this one may well be a pattern for survival and growth, and one as a base for further cross border deals to foster the long held dreams of consolidation in the industry. The second plank of strategic developments highlighted at last month’s Investor Day was a discussion of the long–awaited transatlantic joint venture. On the basis that Anti Trust Immunity will be granted at the end of July – tentative approval was granted by the US DoT in February subject to the modest disposal of four slot pairs at Heathrow (which the group will no doubt recover quite quickly) – British Airways,Iberia, American (along with Finnair and Royal Jordanian as members of the $1 $2 alliance) will finally be able to coordinate on the Atlantic (AA already had been able to coordinate with Finnair under existing ATI agreements). The group plans to move quickly to a full contractual “Joint Business” covering all services between North America/Mexico and Europe, with deeper coordination on beyond and behind routings. BA and American have argued that they have been competitively disadvantaged by the inability to combine forces in face of the ATI granted to the other major European players – and particularly in light of the creation of the four–way joint venture by Air France, KLM Delta (and Northwest) established in 2008 and the expanded Star Alliance ATI in 2009 – and have been trying to gain approval with minimal concessions on and off since 1997. Of course it was the final dismantling of “Fortress Heathrow” — or at least the raising of the portcullis from EUUS open skies two years ago – that allowed the DoT to reconsider in their favour.

Since the opening of the skies over Heathrow, BA has seen a shift of competitor action from London Gatwick into its home base, and the $1 $2 share (aka BA and AA services) of Heathrow–US capacity decline from 61% to 58% in the period. Between Summer 2007 and Summer 2009, the number of daily services between Heathrow and the US has grown by 15% overall – with a 33% jump in services from operators other than BA or American (who combined increased serviced by 6%): equivalent to the growth in the number of operators on the route, as Continental, USAir, Delta and Northwest have gained access (mostly through acquiring or leasing slots at vast expense from their alliance partners). This has changed the competitive landscape sufficiently perhaps to allow the regulators to accept the BA–AA arguments in favour of greater coordination.

The deal is described as a contractual joint venture and referred to as a “Joint Business”. The initial deal is for ten years with declining penalties over time for withdrawal. It is apparently a capacity–based revenue share agreement (rather than a full profit share agreement as with the AF–DL agreement, or BA’s agreement with Qantas on the Kangaroo route) with some excessively complicated agreements for the share of capacity, relative capacity growth and allocation of revenues. Total revenues for the join operations are estimated at $7bn (£7bn or €7bn?) and account for a third of BA’s total revenues, while accounting for some 20% of the Europe–US market. As with the other two joint ventures on the Atlantic the principles involve:

- Metal neutrality – who cares (apart from the customer) what flag is painted on the tail?

- Balanced growth – we can’t upset the exacting unions can we?

- Coordination of key functions – sales, marketing, scheduling and pricing. Neither unions nor passengers will see this – although potential passengers may be glad to see more schedule choices on the website booking engine, while ruing (without knowing) the restrictions on pricing that consolidation should bring.

- Expanded code sharing. 100 transatlantic daily flights, 500 destinations daily in 100 countries, an extensive network developed through the key base hubs of Heathrow, Gatwick, Madrid, New York, Miami, Dallas and Chicago. Departure boards working overtime?

Alliance hopes

- Customer benefits from an expanded network and enhanced service offerings. But perhaps customer confusion from product differences – seat pitch, on–board F&B charges, blanket colours? Intriguingly, the preliminary approval from the DoT in February may have been significantly positive for the future existence of the $1 $2 alliance: JAL, in the process of administration, was debating whether to switch alliance partners (which would have destroyed the strategic entry into North Asia) and being actively courted by Delta to join SkyTeam. American successfully put up a strong fight to retain the Japanese flag carrier – and under the potential of the impending open skies agreement between Japan and the USA should now be able to achieve ATI on the Pacific and create a similar joint venture agreement for traffic between North America and Asia. As with Air France–KLM and KLM’s long standing JV with Northwest, BA can claim significant experience from its decade–long agreement with Qantas on the Kangaroo route, and bring this experience to bear. With ATI it will no doubt be able to share the experience with its North American partner.

One of the key elements of the JV on the Atlantic will be the hub coordination between the networks. At Heathrow the $1 $2 operations will be concentrated on a combination of Terminals 5 (BA only) and Terminal 3 (BA “not so important” + partners). The new T5C satellite (geographically situated between T5 and T3) should open next year along with a baggage transfer tunnel to facilitate network transfers between T5 and T3.

In New York, where American appears to be driving significant growth at Kennedy to compete against Delta’s expansion there (and Continental’s at Newark) there is the potential for BA and IB to co–locate at Terminal 8 – with BA relinquishing its long held terminal 7 at JFK (which it still shares with United after the abortive 1988 link) – to create a single $1 $2 terminal operation, seamless transfer proposition and “leading edge” lounge and premium services. They also say that they should be able to “adopt the very best of (LHR)T5 at JFK”. In the longer term – something not mentioned by the other alliances (yet at least) – is the opportunity for further “optimisation”: selective common procurement (aircraft, fuel, airport charges, GDS and credit card fees); lower per passenger costs through use of larger aircraft on major routes; harmonisation of product; extended collaboration to “include best practices across the groups”.

The hope naturally is to be able to generate combined improved earnings – but not having ATI has precluded them from yet being able to give any hard numbers of the potential. As with all these joint ventures however it will be exceedingly difficult to see in the published figures where the real financial benefits lie – as by their very nature there will only appear a balancing cash movement in the accounts. It may well be that having the three major alliance groupings operating joint ventures on the Atlantic and controlling in excess of 60% of the market will remove sufficient competition to allow each to improve returns; it may be that with all three operating in a “level playing field” that it becomes a zero sum game. In any case, these joint ventures are a poor substitute for full capital mergers – but in the absence of any real political willingness to abandon ownership restrictions it is the only game in town.

| Region | Unique | Unique | Jointly |

| to BA | to IB | served | |

| Asia/Pacific | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| C. America/Caribbean 12 | 7 | 1 | |

| Europe | 40 | 46 | 45 |

| Middle East | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| North America | 19 | 0 | 5 |

| Northern Africa | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| South America | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| Sub-Sahara Africa | 17 | 2 | 2 |

| €m | % | |

| IT | 70 | 28% |

| Maintenance | 58 | 23% |

| Corporate Centre | 35 | 14% |

| Purchasing | 28 | 11% |

| Fleet | 18 | 7% |

| Sales | 15 | 6% |

| Other | 25 | 10% |

| TOTAL | 250 | 100% |

| In Service | On Order | On Option | ||||

| BA | IB | BA | IB | BA | IB | |

| A318 | 2 | |||||

| A319 | 33 | 23 | 1 | |||

| A320 | 39 | 36 | 11 | 9 | 31 | 63 |

| A321 | 11 | 19 | ||||

| A340 | 33 | 1 | 2 | |||

| A380 | - | 12 | 7 | |||

| B737 | 19 | |||||

| B747 | 49 | |||||

| B747-F | 3 | |||||

| B757 | 8 | |||||

| B767 | 21 | |||||

| B777 | 46 | 4 | 4 | |||

| B787 | 0 | 24 | 28 | |||

| Avro RJ | 3 | |||||

| Emb 170/190 | 9 | 2 | 18 | |||

| Total | 243 | 111 | 53 | 11 | 88 | 65 |