JetBlue: Recession? What recession?

June 2009

Many LCCs are currently performing better than legacy carriers, thanks to their more recession–resistant business models. In the US, with leading LCC Southwest facing some near–term challenges (see Aviation Strategy, April 2009), this year’s star performer is likely to be JetBlue Airways. New York’s hometown airline reported its first profitable March quarter in four years and is expected to return to 10%-plus operating margins in 2009 and 2010. Why is JetBlue suddenly outperforming its peers? How has its growth strategy changed?

Now in its tenth year of operation, JetBlue has entered what seems like a new chapter of its development: a maturing carrier, with sustained profit–earning potential and growing international ambitions.

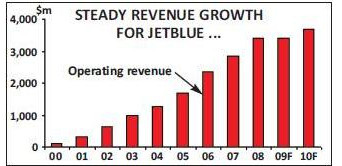

JetBlue had perfect credentials when it commenced operations from New York JFK in February 2000: ample start–up funds, a strong management team and a promising growth niche. It quickly attained Southwest’s efficiency levels, became profitable after only six months and went on to achieve spectacular 17% operating margins in 2002 and 2003. With its new A320 fleet, state–of–the–art technology and superior in–flight product, JetBlue set new standards in airline service quality in the US, which enabled it to attract price premiums and considerable customer loyalty. It also grew extremely rapidly, achieving “major carrier” status (with $1bn–plus annual revenues) in its fifth year of operation.

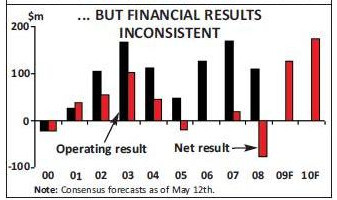

But after the spectacular start JetBlue stumbled financially, seeing its operating margin plummet to the low single–digits and net results turn negative in 2005 and 2006. The airline was struck by a host of negative factors, including higher fuel prices, a weakened domestic revenue environment, lack of international operations, an over–simplified pricing model and an over–aggressive growth plan. Furthermore, an operational meltdown in February 2007 highlighted serious shortcomings in its ability to deal with operational issues. JetBlue tackled its problems with great gusto, spending two years restructuring and refining its strategy with the help of a “return to profitability” plan, introduced in April 2006. Most significantly, it drastically slowed growth through fleet reductions, improved revenue generation through a multitude of initiatives and enhanced profitability through network changes. The February 2007 crisis also led to a leadership change, with president Dave Barger taking over as CEO from the visionary founder David Neeleman.

As a result, JetBlue returned to what was essentially “mainstream” profitability, achieving 6% and 3.2% operating margins in 2007 and 2008. Last year’s modest $23m pretax loss before special items was no mean feat in one of the toughest years in the industry’s history.

But now the signs are that JetBlue could return to substantial profitability – operating margins in the 10%-plus range – in 2009 and 2010, as long as there is no major spike in fuel prices. The airline reported its first profitable March quarter since 2005, earning a 9.3% operating margin in its seasonally weakest period. It was one of only a few sizeable US carriers to post a profit for the latest quarter.

Why is it outperforming?

In investor guidance dated May 21st, JetBlue predicted that it would achieve operating and pre–tax margins of 9–11% and 3–5%, respectively, in 2009. Current consensus forecasts expect even higher margins in 2010. Importantly, the company is on track to meet its 2009 goal of generating positive free cash flow (operating income less capex) for the first time in its history. JetBlue is well–positioned for a number of reasons. First, it has benefited enormously from the decline in fuel prices. Having restructured its out–of–money hedges late last year, JetBlue is now only 7% hedged for the remainder of 2009 and is therefore paying close–to market prices for fuel this year. Based on the forward curve in mid–April, JetBlue predicted that the lower prices would save it $475m in 2009 — roughly equal to 15% of its 2008 passenger revenue (the price of oil is currently somewhat higher, so the benefit could be less).

Second, JetBlue is benefiting because it has put its capacity growth on hold and significantly reduced capital spending through aircraft sales and order deferrals. It acted early to make the necessary adjustments (rather than leaving it till the last minute, like Southwest).

Third, JetBlue has been very successful in developing ancillary revenues to offset some of the fare weakness. Key initiatives such as “Even More Legroom” (a new “front cabin” product introduced on the A320s in March 2008), second checked bag fees and increases in change fees helped almost double ancillary revenues to $350m last year (10% of total revenues). In the March quarter, when JetBlue’s average fare fell by 1.7% to $133, ancillary revenues per passenger rose from $12 to $19.

Many of the ancillary initiatives have shown less sensitivity to the weakened economic environment. There is further potential to develop those revenue sources; in particular, adding a first checked bag fee could be lucrative (JetBlue and Southwest are the only holdouts). JetBlue expects its ancillary revenues to grow by 20% in 2009.

Fourth, in the past 18 months JetBlue has also produced industry–leading passenger revenue performance. Its PRASM rose by a stunning 14% in 2008, reflecting a 13% increase in the average fare. When the recession began to bite in the March quarter, JetBlue’s PRASM remained flat.

As a result, JetBlue has led the industry in monthly year–over–year unit revenue growth in the past 12 months. In the March quarter, its RASM was up by 2.7% (thanks to ancillary revenues), compared to the domestic industry average decline of 10%. The current (May 21) expectation is that RASM will fall by 2–5% in 2009. With load factors holding up, especially in peak travel periods, JetBlue’s revenue outlook is clearly not that dire.

Like other LCCs, JetBlue is avoiding the worst effects of the recession because of its lack of exposure to global markets and premium traffic generally. Some 84% of its operations are in the domestic market, which is seeing the benefits of large industry capacity reductions. The remaining 16% of its capacity is in the US–Caribbean/Latin America markets, where PRASM growth has remained strong despite capacity addition. Those markets also have significant VFR traffic.

But JetBlue is also attracting new business customers looking for value in a tough environment. It is seeing anecdotal evidence of especially small and medium–sized businesses switching over from the legacies.

JetBlue is well–positioned to attract business traffic because it is probably the most upscale of the US LCCs. It offers a unique value proposition, strong brand and great customer service. The basic value proposition, as stated in JetBlue’s annual reports, is that “low fares and quality air travel need not be mutually exclusive”.

In the past two years, JetBlue has moved aggressively to cater for the higher–yield segment with strategies such as Even More Legroom, offering refundable fares and listing fares in all four major GDSs. At the same time, JetBlue continues to aggressively woo the leisure segment with fare sales and gimmicky offers aimed at stimulating demand and attracting new customers. Recent efforts have included a “Promise” programme that guarantees a full refund to anyone who loses their job prior to their trip and one–day “sample sales” that offer transcon flights for only $14 each way or “less than what other airlines charge for a single bag”.

Promotions like that have minimal negative impact on yield – certainly much less than the extensive fare sales initiated by other airlines in recent months; rather, they encourage product trial and awareness. The offers are based on the premise that the product is so attractive that people only need to try it once and they become loyal customers.

Of course, the key factor behind JetBlue’s improved revenue performance is that it now has much more flexibility in yield management and revenue generation, having upgraded its systems and revamped its revenue management team three years ago.

But JetBlue faces significant non–fuel cost pressures. Its ex–fuel CASM surged by 9% in the March quarter and is projected to be up by 9–11% in 2009. This could well be the industry’s worst cost performance in 2009.

In the current circumstances that does not really matter, because total CASM is likely to fall significantly in 2009 due to lower fuel prices (which would offset by a wide margin the expected RASM decline). But non fuel costs could become an issue at JetBlue if oil prices surge without a corresponding improvement in the demand/revenue environment.

The hike in ex–fuel CASM in the first quarter was attributed to two factors: the shrinking ASM base (down 5%) and a shorter average stage length (down 6%, as JetBlue shifted capacity from the transcon to shorter haul markets). Maintenance unit costs were up by a substantial 19%, due mainly to the first of the E190 fleet entering heavy maintenance checks.

JetBlue is seeing cost pressures also because of its no–furlough policy. Like Southwest, JetBlue wants to protect its brand and culture, as well as keep making investments in the infrastructure necessary for growth.

Disciplined growth

The management is particularly mindful of these issues at the moment because of a recent unionisation threat. JetBlue has no unions, but this past winter its pilots sought to organise, not because they had any problem with the current leadership but because they wanted to ensure a strong position with a future management that may be less friendly to labour. The effort failed, with only 33% of the pilots voting for union representation. The management noted recently that a direct relationship with workers is a huge competitive advantage and that important lessons had been learned from the pilot campaign. and spending Slower growth has been the key factor behind JetBlue’s financial recovery. The airline reduced its ASM growth from an annual average of 25% in 2003–2006 (when it was one of the fastest growing US LCCs) to 12% in 2007 and only 1.7% last year. The current plan envisages flat capacity in 2009.

The ASM growth reduction has been achieved through a combination of older aircraft sales, lease terminations, order deferrals with Airbus and Embraer, reduced utilisation and aircraft gauge reductions (substituting E190s for the A320s). JetBlue is fortunate to have one of the industry’s highest A320 utilisation rates, still averaging 12 hours daily in the first quarter (down from 12.9 hours a year ago).

JetBlue initially focused on aircraft sales – a tactic that also raised useful extra liquidity in 2006 and 2007. As the A320 resale market softened last year, the focus shifted to order deferrals. Having already rescheduled some near–term deliveries in 2007, during the first half of 2008 JetBlue deferred the delivery of 37 A320s and 10 E190s from 2009–2011 to 2012 and beyond. Recent months have seen a further modest trimming of the E190 commitments – some delivery deferrals and the sale of a few E190s to Azul.

Overall, JetBlue has managed the rapid capacity pull–down rather well in a tough environment, selling lots of aircraft when the market was strong and taking advantage of its special relationships with Airbus, Embraer and Azul. JetBlue’s top executives commented in late April that they were happy with the current size and composition of the fleet – 110 A320s and 37 E190s, totalling 147 aircraft, as of March 31st. Further aircraft sales will be considered if opportunities arise, but any such sales would probably be offset by option conversions.

JetBlue now has extremely modest firm order commitments for 2009 and 2010. After adding three A320s and two E190s in the first quarter, the airline is taking four E190s in the current quarter and has no further deliveries in 2009. One A320 lease return is scheduled for November. Next year JetBlue is committed to taking only three A320s; with one lease return and assuming no aircraft sales, the fleet will grow by only two aircraft in 2010. Commitments for 2011 are also modest: five A320s and four E190s.

All of that means a significant reduction in aircraft capital spending: only $315m in 2009, $215m in 2010 and $470m in 2011. By comparison, JetBlue had aircraft capex of $1.1–1.3bn annually in 2005–2006.

Of course, JetBlue retains a significant aircraft order book that will facilitate growth in the longer term. Currently, firm deliveries are picking up sharply in 2012 and will average around 25 aircraft (evenly split between the A320 and the E190) and $1bn spending annually in 2012–2014. At the end of March, the total firm order book consisted of 55 A320s and 64 E190s for delivery through 2016, plus 21 A320 options and 83 E190 options for delivery in 2010–2015.

However, as a maturing carrier, JetBlue is not likely to return to double–digit annual ASM growth. The management suggested recently that 5–10% might be a sustainable future growth rate.

Like other LCCs, JetBlue wants to maintain the flexibility to respond to market opportunities that might crop up during this recession. At the other extreme, if economic conditions worsen significantly, the high aircraft utilisation rates give JetBlue flexibility to further reduce capacity.

In addition to the goal of achieving free cash flow this year, JetBlue is focused on maintaining a strong balance sheet. The past 18 months have seen an impressive liquidity–raising spree. First, JetBlue found a unique solution to the cash concerns it had in late 2007: selling a 19% ownership stake to Lufthansa for $300m. That transaction restored JetBlue’s cash reserves to a very comfortable 20%-plus of annual revenues.

After the Lufthansa investment, JetBlue continued to take actions to bolster liquidity and strengthen its financial position. Among other things, it raised $201m through a public convertible offering, obtained a new $110m secured bank credit line, refinanced debt and repaid as much as $500m in debt last year.

Those actions, first of all, significantly reduced this year’s debt maturities. JetBlue expects its scheduled principal payments for debt and capital leases to be only $160m in 2009, down from $700m last year.

Second, JetBlue has maintained a solid liquidity position. It had $634m in cash at the end of March – 18.7% of last year’s revenues, which was slightly better than the legacy carriers’ and Southwest’s positions.

Network and alliance plans

With lower fuel prices, extremely modest capex and financial obligations, this year’s aircraft fully financed and only three deliveries scheduled in 2010, JetBlue seems well positioned to weather this recession. JetBlue has been optimising its network and expanding strategically. The past year has seen three broad themes. First, the pace of Caribbean/Latin America expansion has intensified. Second, last winter JetBlue removed a significant chunk of its transcontinental capacity. Third, JetBlue is growing in selected focus cities, including Boston, Orlando and Los Angeles.

The Caribbean, which JetBlue has called “a natural out of New York”, has been a brilliant move for the carrier. The markets have year–round demand, have matured quickly, generally require minimal up–front capital, generate higher revenue than domestic flights of comparable distance and, in spite of limited daily frequencies, are relatively low cost. Those markets have continued to see strong RASM improvements.

The past six months have seen significant new Caribbean/Latin America expansion. JetBlue has added Bogota (Colombia) as its first South American city, San Jose (Costa Rica) and Montego Bay (Jamaica). It has also been “connecting the dots”, giving focus cities such as Ft. Lauderdale, Orlando and Boston numerous new Caribbean connections. The 100–seat E190 has played a key role in facilitating service in some of the Florida–Caribbean markets.

Although JetBlue has had to temporarily reduce its Cancun (Mexico) schedule this summer because of swine flu, its rapid expansion in that market gives an indication of the success of the Caribbean operations. The JFKCancun service was launched in late 2006; now, with Ft. Lauderdale getting its connection in June, JetBlue will be operating to Cancun on a nonstop basis from six US cities.

JetBlue is adding Barbados and Saint Lucia to its network this autumn, bringing its international destinations to 13. By year–end the Caribbean/Latin America region is expected to account for more than 20% of JetBlue’s ASMs, up from 10% two years earlier.

In contrast, transcontinental markets have been particularly weak because of aggressive fare sales. JetBlue stepped up capacity cutting on those routes in mid–2008, even though it had already significantly reduced its exposure to transcon in the previous two years. East–West services had accounted for 55% of its ASMs at the end of 2005, but by late last year the percentage had fallen to the mid–30s. The removal of a big chunk of capacity in the first quarter brought East–West’s share down to 27%, though it is expected to be around 30% at year–end. The management feels that 27- 30% is “in the right range”.

It would seem that the recession has helped JetBlue achieve a more balanced network, with East–West accounting for 30%, Caribbean/Latin America 20%, Northeast- Florida around 32% and other/short–haul the remaining 18% of ASMs.

Of course, transcon remains a core part of JetBlue’s network, a market that it is going to defend. JetBlue is actually launching two very high–profile transcon routes this month. It will start serving Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) from JFK and Boston on June 17 to complement its existing transcon operations to Long Beach, Burbank, Ontario and San Diego in Southern California. The new services were originally due to start last summer but were postponed due to fuel costs.

The move is partly a response to Virgin America, which began operations out of San Francisco in August 2007, and is aimed at maintaining JetBlue’s position as the leading LCC in the key transcon markets.

The decision to serve all three LA Basin airports (LAX, Long Beach and Burbank) is an interesting one. It partly reflects the fact that LA customers have strong preferences for particular airports because of severe congestion on the roads. Then again, JetBlue has a similar strategy for the New York area, where its operations cover JFK, LaGuardia, Newark, Newburgh and Westchester airports. This “multiple airport area” strategy may sound unusual for an LCC, but it is probably very effective in protecting market share from inroads by new entrants.

Of course, JetBlue’s greatest strength is its dominant position in New York, the world’s largest air travel market. The airline intends to continue to leverage its presence at JFK, which accounts for 60% of its operations. The key development on that front was the opening of JetBlue’s new Terminal 5 in October 2008.

The JFK base makes JetBlue perfectly positioned to develop alliances with international carriers. The airline has not commented much on this subject in recent months, but back in January it provided an update on the two existing relationships. The internet booking partnership implemented with Aer Lingus in April 2008, which currently covers JFK and Boston, is meeting expectations and may be extended to Orlando this year. Commercial cooperation with Lufthansa, JetBlue’s largest investor, is expected to start in the second half of 2009.

The basic message coming from the leadership is that JetBlue is open to alliances with more international carriers. Like Southwest, JetBlue has needed time to develop the technology to handle multiple international partnerships and possible code–shares. One important new development is that over the next year JetBlue will be switching from Open Skies to the more sophisticated Sabre reservation system – a move that reflects its growing presence in near–international markets and a serious intent to forge global partnerships.