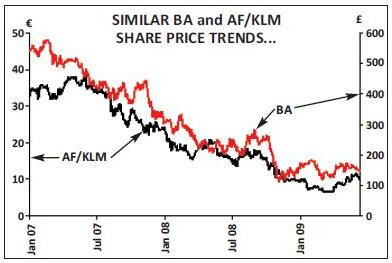

British Airways and Air France/KLM: Different prospects?

June 2009

In the past month both British Airways and Air France/KLM have published their annual results for the year to the end of March – and they were as dire as expected. So what are the prospects for these two European giants?

Air France/KLM reported full year net losses of €814m, down from a restated €756m profit in 2007/08, and BA revealed net losses of £358m in 2008/09, down from profits of a restated £726m in the previous financial year. These results showed the disastrous impact of an external shock to the fragile economics of running an airline – and neither company was willing (or even able) to provide the markets with guidance for profitability in the current financial year; quite reasonably the management of each have very little visibility of economic performance in the medium–term.

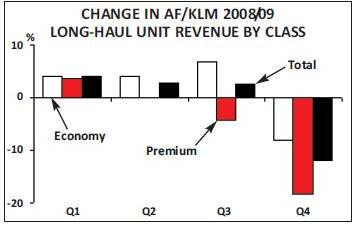

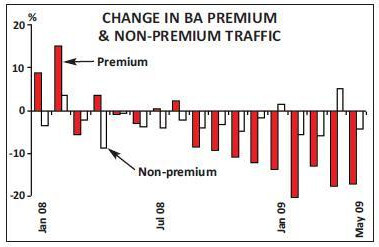

There are many similarities between the two airlines’ performances. Both companies displayed disastrous revenue performance in the weak fourth quarter of their financial years, with double digit unit revenue declines and extraordinary weakness in the important premium passenger segments. Both registered significant losses on fuel hedges as well as recording losses as a result of the mark–to–market rules. Both airlines had to suffer the apparent negative consequences on the balance sheet of the ridiculous new accounting rules for frequent flyer liabilities (albeit positive to the P&L). Both emphasised further reductions in capacity plans for the short run, deferrals of aircraft orders and acceleration of aircraft disposals in an attempt to bring the supply of capacity closer into line with the recent drop in demand. Finally, both highlighted their plans to emphasise cost reductions.

Air France/KLM

The differences between the airlines probably reflect national characteristics. AF/KLM appeared to be more optimistic in expecting a recovery in traffic demand towards the end of this year. In contrast, BA appeared to believe that the economic doldrums will last some while longer – and even emphasised the oft–held view (and arguably mistaken because it all depends on how you draw the trend lines) that industry growth never returns to previous trends after a major shock to the system, and that a year or two’s growth has been permanently removed from the trend by this recession. Both companies, however, show the extreme difficulty of running an airline when the revenue base disappears, and are likely to find it exceedingly hard to avoid further significant losses in the current year. Air France/KLM reported fourth quarter revenues some 12% down on the prior year period at €5bn, and an operating loss of €574m, down from losses of a restated €37m last time. This includes the first–time full consolidation of Martinair from January 2009 (after decades of trying, KLM finally managed to get agreement to buy in the 50% it did not own), which added 3% to total group revenues and losses in the quarter.

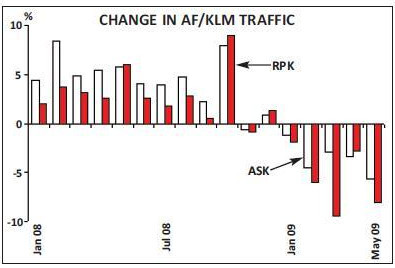

In the passenger division, capacity in the period was down by 2.7% year–on–year while traffic in RPKs fell by nearly 6% and unit revenues fell by 9% (with European short–haul particularly badly hit, registering an underlying 18% drop in unit revenues). Total passenger revenues fell by 14% to €3.7bn. Operating losses came in at €402m, down from profits of €8m last time. Cargo operations were even worse hit, but the interpretation of the results is a little confused by the inclusion of Martinair, which added some 10% to total group cargo capacity and some 20% to traffic in RTK. Total capacity (which includes the passenger division’s belly–hold capacity) was up by 11.5%, while cargo traffic was on a par with prior year levels. Excluding Martinair, however,capacity was down by 10% and traffic demand by a whopping 21%.

Unit revenues – somewhat affected by the removal of fuel surcharges from the end of calendar 2008 – fell by nearly 30% and total divisional revenues (after including the results from Martinair) fell by 19% to €550m. Operating losses came in at €165m, down from a near break–even last time. The maintenance business meanwhile reported a modest 1% improvement in revenues and recorded a €47m profit after a small loss last time – helped no doubt by the strength of the dollar in the period.

For the full year, total group revenues were little changed on 2007/08 at €24bn while the group achieved operating losses of €129m, down from peak profits of €1.4bn. In the passenger division, full year capacity was up by 2%, demand down by 1% and unit revenues down by 4% (or 2% excluding currency movements). Total divisional revenues fell by 1% and the previous year’s record €1.3bn profit turned into a €21m loss. Cargo operations for the full year showed capacity up by 2%, demand down by 5% and unit revenues down by 4.7% (or 4% excluding currency), with modest operating profits in the previous year of €40m turned to a €200m loss. Total group operating losses came in at €193m, down from profits of €1.3bn. Finance charges were little changed from the previous year, but the real financial killer for the year was a book entry charge for currency losses and the mark–to–market of fuel and currency hedges of a massive €894m (against a mere €6m last time), while associate company losses doubled to €42m (even though the company stated that their 25% stake in the “new improved” Alitalia had no impact on the 2008–09 results). Altogether, the previous year’s peak profit of €750m turned into a loss of €814m.

While overall group revenues were at a similar level to the previous year, unit costs grew by 3% and total costs rose by 6%; with fuel costs up by 25% year–on–year to €5.7bn (or 23% of total operating costs). In the fourth quarter there was an underlying 9% reduction in the cost of fuel (excluding Martinair) and a near 5% decline in unit costs. Air France/KLM had started earlier in the year to accelerate cost savings as part of the “Challenge 10” targets (see Aviation Strategy, November 2008) and the management stated that it had achieved a full year target of €675m against initial plans of €430m – with €185m additional savings achieved in the fourth quarter alone.

Operating cash flow for the year consequently slumped to €798m from €2.6bn in the previous year (after allowing for the €225m cargo pricing cartel fine), while capital expenditure was only 15% lower at €2bn. There was a net cash outflow of €1.1bn for the full year, but this still left the group with cash of €4.3bn (still a reasonable 17% of revenues), although net debt of €4.5bn was up from €2.7bn last time. The group’s shareholders' funds, however, fell sharply; the implementation of IFRIC 13 removed some €640m but there was also a massive €3.3bn swing from the mark–to–market in the value of hedging derivatives. Published shareholders' funds slipped to €5.7bn, producing gearing levels around 70%.

Lower exposure to premium

In its presentation management highlighted its strategic focus as “adapting to the current environment while maintaining a platform for future growth”. In the passenger division the group has cut further its capacity plans; with an overall 4.5% reduction in ASKs for the summer season; this includes an 8% reduction on the North Atlantic, 7% on Asian routes, 5% on European, 6% on French domestic routes, 4% on the DomTom routes to the Caribbean and Indian Ocean, 3% on the Middle East, a 1% reduction on the south Atlantic (although this may be reduced further after the tragic loss of an A330) and a 5% increase in capacity on African routes. Almost for the first time, the company took delight in emphasising that the group has a far lower exposure to premium traffic (or at least that its long–haul premium cabins are far smaller) than the other main network carriers – although it will be installing a premium economy cabin, with all its 777s refitted by March 2010. In the cargo division it is parking six freighters (out of its total fleet of 16) providing an overall 11% reduction in capacity. The acquisition of Martinair in this context may appear a little bit of bad timing: nine of its 13 aircraft are full freighters and 75% of its annual €700m revenues (last year at least) came from cargo operations. However, being merged in with Transavia there should be some long term synergies, while there are seen to be strong operational benefits at Schiphol.

Air France/KLM doesn’t exactly have the same flexibility on staffing levels as British Airways may appear to have, but it has reacted as best it can. Last year it halted recruitment and encouraged early retirement; this and natural wastage provided a 2.5% reduction in headcount (and 3.6% reduction since September 2008) and an underlying fall of 2% in employee costs in the fourth quarter. Recent wage agreements with the unions provide a modest salary uplift of only 1% (slightly less at AF), while the group is trying to encourage early retirement, furloughs and part–time working. The aim is a further 3% manpower reduction in the current year and an underlying reduction in full–year staff costs. Meanwhile, depending on volatility, although fuel has been creeping up again, there should be a near $2bn reduction in total fuel costs in the current year.

In the longer run the group will be trying to reinforce its “Challenge 12” cost reduction plan as it continues to try to achieve the cost synergies from the merger with KLM. Cumulative annual savings so far have been identified at some €1.2bn, with an additional €600m targeted for the year to March 2010. By the year ended March 2012, the group hopes to have achieved total cumulative savings of €2.6bn.

Management would not be drawn on the plans for the coming winter capacity (although it seems to suggest that the current suspension of the 80/20 rule — allowing it to reduce frequencies into London and Frankfurt this summer — may well be extended into the off–season and allow a greater level of flexibility). In the medium–term, helped by the flexibility in the fleet ownership mix, the group has reduced its fleet plans; through renegotiation and deferral of delivery slots and non–renewal of expiring leases it now plans no growth in its 180–strong long–haul fleet in the next two years (although the A380s will be creating seat capacity increases), with the number of aircraft some 14 below original plans. This will have a useful impact of deferring capital expenditure with an anticipated spend of €1.4bn in the current year and €1.8bn in 2010–11 compared with original plans of €2.9bn in each year.

One distinct competitive advantage for Air France/KLM is the start of the full joint venture on the Atlantic with Delta from April 2009. Signed for an initial 10 year contract (as the original KLM–Northwest joint venture was 20 years ago), this encompasses a fully–integrated cooperation on all routes between North America and Europe, and close coordination on routes between Europe and South America and between North America and Middle East, Africa and India.

BA: opaque quarter

The fully immunised joint venture (although Brussels is still not really sure how to treat these ATI alliances) claims a 25% share of the Atlantic market and an operation of $12bn in revenues involving a network linking six main hubs of CDG, AMS, ATL, MSP, DTW and JFK. Of course they miss out on access to London — still the principal gateway on the Atlantic — but incidentally the SkyTeam partners will all be moving into Heathrow’s Terminal 4 in the autumn. Management conservatively expects to be able to generate additional annual network benefits from the joint venture on the order of €145m. Coincidentally the management also stated that it expects to extract some €160m in synergies from its 25% stake in the reborn Alitalia by 2012. BA meanwhile reported its fourth quarter revenues down by 8% to £1.9bn and an operating loss for the period of £309m, down from a profit of £134m last time. Since the move to reporting “interim management statements” and the withdrawal from the NYSE, BA’s quarterly reporting is somewhat more opaque than some of its competitors, and even more than usual the interpretation of the individual quarters through the year requires more head–scratching, or at least some decent spreadsheet modelling.

However it looks as if the company also fell into an EBITDAR loss of over £100m in the quarter. In the three months capacity fell by 3%, demand by 5.6% and unit revenues by 6%. In this it was helped significantly by the weakness in the exchange rate (particularly against the Euro) and excluding currency effects unit revenues probably fell by nearer 20%. Cargo plays a smaller part in BA’s operations. Cargo demand fell by 15% year–on–year although — helped by currency — yields were only down a couple of points and total cargo revenues were down by around 17%.

For the full year, seat capacity was only 1% down on the prior year period, passenger traffic down by 3.4% and unit revenues up by 3.3%. Total passenger revenues consequently for the year grew by 3% to £7.6bn. Full year cargo operations meanwhile experienced a 9% growth in revenues – mainly because of fuel surcharges to £673m. Below the operating line the company only had a £106m book entry charge for the idiocies of current accounting rules. Pre–tax losses for the year came in at £401m (including £75m restructuring costs), down from a restated peak £922m profit for 2007/08.

BA had the additional burden of the transfer to Terminal 5 at Heathrow, with a particular impact in the first half of the year. Total unit costs (per ATK) excluding fuel were up by nearly 10% year on year – although when accounting for the decline in Sterling this comes down to an underlying 3% increase. Having built manning levels at Heathrow in anticipation of the move to the new terminal, the company was able gradually to improve efficiencies through the year, while the improvements in operational performance provided by the new facility helped significantly reduce avoidable costs (particularly relating to baggage). In the fourth quarter of the financial year underlying unit costs (excluding fuel and exchange) were actually down marginally year–on–year. Fuel costs in the fourth quarter were still up by more than a third and for the full year by 45% to £3bn – an uncomfortable 32% of operating costs – with the hedging gains in the first half of the year offset by similar losses in the second. With 55% of the current year fuel burn covered (at a break–even of $75/bbl equivalent, and heavily weighted to the first half of the year) the company expects the total fuel bill in 2009/10 to be some £400m lower.

Gross operating cash flow in the year fell to £474m from £1.5bn, while capital expenditure fell by 10% to £550m and cash and cash equivalents ended the year at £1.4bn (or 17% of annual revenues), down from £1.8bn at the end of March 2008. As at Air France, BA ended the year with a significant reduction in equity on its balance sheet: the introduction of IFRIC 13 — the new accounting rules for FFPs — had the impact of reducing shareholders' funds by £206m, but ironically this was more than offset by a boost of £235m for the adoption of IFRIC 14 (accounting for employee benefits). However, BA also suffered a reversal in the fair value of derivatives of some £988m and balance sheet equity more than halved to £1.4bn from £3.1bn. As a result net gearing at the year end had risen to 125% from 40% a year ago.

Survival short-term, competitiveness long-term

An additional idiosyncrasy (in the European market) is BA’s pension fund position, and it is hardly surprising that the Iberia board has found it difficult to understand. At the end of March it appears on the balance sheet that BA has a surplus of benefit assets to obligations: this reflects the oddities of the accounting treatment which among other things discounts the liabilities according to corporate bond rates (which through the financial crisis have been unusually high in real terms); if the full accounting deficit were shown the balance sheet equity position would be significantly worse. The actuarial valuation (which determines the annual payments into the funds) is likely to show a significant further increase in deficit — meaning that the company will have tough negotiations with the trustees to keep payments into the fund at affordable levels. Although management naturally would say nothing, this gives rise to the question of whether the company will need to raise equity through a rights issue. Somewhat similar to its French rivals, the BA management in its presentation emphasised a dual focus but managed to express it more pithily: short–term survival, long–term competitiveness. Not unfairly stating that this current environment reflects the “toughest economic climate” in its history, the company outlined its medium–term plans – but would not be drawn on giving any forecasts.

Capacity this summer has been trimmed back again by an additional half a point, showing a reduction of 2.5% — taking advantage of the suspension of the “use it or lose it” rules. For the winter season the company has decided to ground an additional eight 747s and eight 757s (and recently announced the sale of the whole of the 757 fleet, for disposal into the cargo markets next year), providing a preliminary 4% reduction in capacity (having originally planned a 5% growth).

Unlike AF/KLM, however, the BA team deems it unlikely that Brussels will allow the suspension of the 80/20 rule to continue into the winter season: if it does expect BA to reduce short–haul capacity even more aggressively. In the medium to longer term BA retains flexibility to reduce capacity further as more of the older 747s achieve their 20th birthdays, while it has also deferred the replacement of its aging 737 Classic fleet at Gatwick, originally slated for 2012/13. As always, cash is king and the company is reviewing all its fleet plans, and no doubt is in negotiation with both manufacturers to defer deliveries (and address the resulting timing mismatch between capex and arranged financing).

In hand with this, the company is clamping down on non–essential capital spending and is taking an extreme focus on all costs, aiming for a significant cut in its annual £5bn external supplier spend (CEO Willie Walsh even apologised for banning the hiring of consultants). BA has apparently had reasonable success in negotiations with most unions (with the exception of the cabin crew) to address pay, productivity and working practices, while emphasising a pay freeze and offering furloughs and part–time working. At least with the move to Terminal 5 there is now a substantial improvement in the underlying efficiency of the BA base of operations – not least of which is the improvement in the baggage handling performance (down from more than 80 missed bags per 1,000 passengers in 2007/08 to under 50, and a current year target of 35/1,000; the company expects to save some £12m annually in compensation payments).

One additional benefit is that BA’s transfer offer through Heathrow becomes significantly more competitive, ironically helped by the weakness in Sterling, and noticeably since November last year BA has been targeting connecting traffic (particularly attacking flows in strong currency markets) – with significant increases in the proportion of its traffic using Heathrow as a transfer.

The future

Meanwhile, the management said very little about its industry consolidation moves – hardly surprising in the circumstances. The application for anti–trust immunity with American has now been finalised and before the regulators. Both BA and AA appear fairly confident that approval will be granted on both sides of the Atlantic and expect a result by the end of October. The deal with Iberia meanwhile appears to have stagnated – Willie Walsh stated that the two sides are still discussing corporate governance issues. No doubt the Iberia board is also still confused by the whole issue of the pension deficit. This current worldwide recession and cyclical industry downturn has been swift and deep. But BA and AF/KLM (and Lufthansa) are substantially better prepared than many, and have possibly introduced a greater level of flexibility into their operations (notwithstanding the natural cultural differences) than many others have been able to do. They had succeeded in developing sound balance sheets before the crisis hit, while this very crisis should help to allow them each to go even further. There should at some time be an economic recovery, businesses will at some point start travelling again, trade will start to flow and consumers at some point will regain confidence. When that happens, both airlines should be able to bounce back stronger than before.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| A380 | 12 | 2 | |

| A330 | 25 | 2 | 21 |

| A340 | 19 | ||

| 747* | 35 | ||

| 767** | 6 | ||

| 777 | 69 | 21 | 3 |

| MD-11 | 13 | ||

| A320*** | 150 | 16 | 16 |

| 737 Classic | 22 | ||

| 737NG | 68 | 16 | 4 |

| Regional aircraft | 203 | 29 | 31 |

| Passenger total | 610 | 96 | 77 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 747F | 10 | ||

| 777F | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| MD-11F | 4 | ||

| Freighter total | 16 | 3 | 3 |

**Including three Combi aircraft.

***Including six A319LRs.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| A380 | 12 | 7 | |

| 747 | 55 | ||

| 777 | 42 | 7 | 8 |

| 787 | 24 | 18 | |

| A320 | 80 | 12 | 136 |

| 737 | 22 | ||

| 757* | 9 | ||

| 767 | 21 | ||

| TOTAL | 229 | 55 | 169 |