Jet/Sahara vs Air India/Indian in the battle for international markets

June 2007

Following the imminent acquisition of Air Sahara by Jet Airways and the merger of Air India and Indian, two large airline groups will compete head–on for the growing international market to/from India. How successful will the integration of Air India/Indian and Jet/Sahara be, and how will they fare in the battle for international passengers?

The Indian market has long been recognised as having great potential but in the last three years the Indian government’s gradual liberalisation of the aviation industry has sparked a huge increase in capacity, particularly domestically. Until four years ago only Jet Airways and Air Sahara provided domestic competition to Indian, but in 2007 competition comes from Air Deccan, Kingfisher, Go Air, SpiceJet, Paramount, Indus and IndiGo, and at least four new airlines are seeking approval to being domestic services.

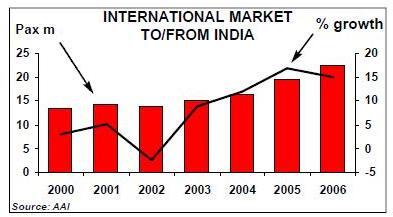

According to the Airports Authority of India (AAI) passengers carried on Indian domestic routes have risen from 13m in 2002 to more than 25m in 2006, with domestic traffic increasing by around 28% in 2006 compared with 2005. The domestic rate of growth is expected to slow down to "just" 15%-25% per annum over the next few years, but it will continue to be fuelled by the expansion of the Indian urban middle classes (who number around 300m at present) and a steady conversion of passengers from rail to cheap air routes. Longer–term, many analysts see further potential from the tourism market, which is relatively underdeveloped.

However, in the short–term, as more domestic capacity has flooded into the market and fares have dropped, the industry has had to contend with falling domestic yield. So while over the last three years the size of the fleet at Indian airlines has more than doubled, from 130 aircraft to approximately 300, and although passengers carried have risen almost as fast, load factors still hover in the mid–60s, and the Indian aviation industry is expected to report a collective loss of some $400m-$500m in 2006/07 (at least for the full–service airlines).

On international routes, according to AAI, passengers have risen from 14m in 2002 to more than 22m in 2006 (see chart, left), and international traffic is expected to keep rising in the double digits per annum over the next few years.

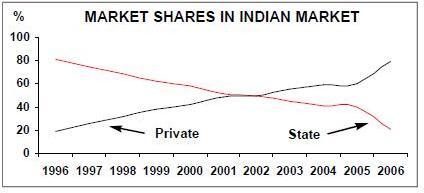

Until recently the government has been reluctant to encourage international competition, and non–domestic routes were offered by just the two state–owned carriers (Air India and Indian Airlines) and two private airlines (Jet Airways and Air Sahara). But increasingly liberal bilaterals and a recognition of the fact that Indian airlines have just a 25% market share of international traffic to/from India have prompted the government to ease restrictions on other Indian airlines that want to operate internationally. At the moment only airlines with a minimum of 20 aircraft and a five–year track record of operating domestically are allowed to apply for international route licences, but the Indian civil aviation ministry is reviewing these rules, and it is likely that the five–year regulation will be the first to be eased, although on certain international sectors only.

Those sectors will include south Asia — on which any private Indian airline is now allowed to compete (although within the existing restrictions as listed above) — and the Gulf region, the latter of which the government plans to open up to more private Indian airlines in 2008.

Jet and Sahara

In preparation for this opening up of the international market, the government has finally pushed through the long–awaited merger of Air India and Indian Airlines, but at the same time Jet Airways is completing its on/off acquisition of Air Sahara (the only private airlines currently allowed to operate internationally). The scene is now set for what will be a hard–fought battle between these two airline blocks internationally, with each wanting to establish itself on the most lucrative international routes before competition from other private Indian airlines pours in.Mumbai–based Jet Airways was launched in 1993 and initially flew a handful of 737- 300s on domestic routes, before becoming the first private airline to launch an international route, to Colombo in 2004. Jet carried out an IPO on the Bombay stock exchange in early 2005, with 20% of equity currently on free float and 80% held by Tailwinds, which is owned by Naresh Goyal, the billionaire (in US$ terms) chairman of Jet.

Following the IPO, Jet began to expand its fleet and both its domestic and international network, and today the airline has almost 10,000 employees and operates to 51 destinations (with Brussels the latest, added in May), of which seven are foreign, and with hubs at Calcutta, Chennai, Delhi and Bangalore. Jet is easily the largest private airline in India and it is now the market leader domestically, with a 28.4% share as at September 2006 (according to Indian government figures), ahead of Indian Airlines (21.7%), Air Deccan (19.3%), Air Sahara (9.1%), Kingfisher (9.4%) and SpiceJet (6.8%).

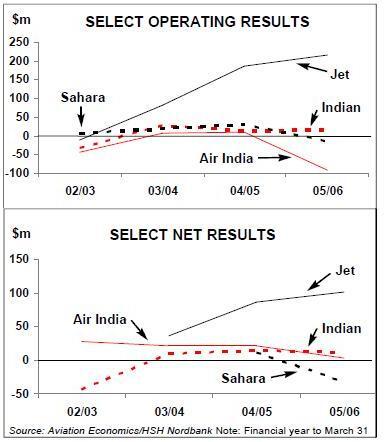

In 2005/06 (with the financial year ending on March 31), Jet reported a 17.4% rise in both operating profit, to $218m, and in net profit, to $102m, and in the third quarter of Jet’s current financial year (October- December 2006, which is the company’s busiest quarter), revenue rose 35.4% to Rs20.3bn ($457.3m), of which international revenue accounted for 22% (up from 14% in September–December 2005). However, EBIT fell 10.4% to Rs2.3bn ($52.9m) in the quarter, and net profit fell 34.4%, to Rs400m ($9m), thanks to increasing competition and higher fuel costs, which rose 36% in the quarter, to Rs6.1bn ($138m). Passengers carried in the quarter rose 14% to 2.7m, with traffic growth of 31.6% just behind a 33.3% rise in capacity, leading to a 0.8 percentage point fall in load factor, to 69.3%.

Domestic load factor of 70.1% was down 2.4% compared with October–December 2005, reflecting the increase in domestic competition, with Jet’s domestic capacity up 15%. Pre–tax profit on domestic services was Rs733m ($16.5m), 43.7% down on the same quarter in 2005. International load factor was 67.6%, 5.2% down on the previous year, but international routes made a pre–tax loss of Rs113m ($2.5m) in the quarter, an improvement on the $7.7m loss in 3Q 05/06. Jet hints that all its international routes are profitable other than those to the UK, and it is addressing those routes through better yield management

However, these 3Q net profits were wiped out by losses in the first two quarters of the financial year (April–September), and for the first three–quarters of the FY (April- December 2006), although revenue rose 32.7% to Rs55.3bn ($1.2bn), EBIT fell 51.2%, to Rs4.1bn ($92.4m), and the airline recorded a net loss of Rs601m ($13.5m), compared with a Rs2.2bn ($50.7m) net profit in 1Q–3Q 05/06. In the first three quarters of 2006/07, Jet made a pre–tax loss of $44m on international routes, and a $28m pre–tax profit on domestic routes (with a $28m loss internationally and a £108m profit domestically in 1Q–3Q 05/06).

The trend in domestic business is clear, and in the third quarter of 2006/07, while Jet’s overall yield fell 2.4% compared to a year earlier, international yields rose 18.2%, thanks to a higher proportion of business class passengers. Unsurprisingly, the airline sees its future profitability driven by international expansion, and in April this year Jet finally agreed terms to buy Delhi–based Air Sahara, after a saga that had gone on since January 2006, when a "deal" between the two was first unveiled, at a price of around $500m. But that agreement collapsed over the summer of 2006, leading to a fierce legal battle between Jet and the Sahara Group, the conglomerate owners of Air Sahara, with the Group accusing Jet of walking away from the deal.

An arbitration panel was assembled to rule on the legal dispute, and the end result was the surprise resurrection of the deal this year, although at reduced price. The acquisition is expected to be completed formally by the summer, and Jet has agreed to pay the Sahara Group a total of Rs14.5bn ($327m) in instalments (with the last payment due to be made in March 2008).

Some analysts are critical of the rationale and pricing deal for a loss–making airline that has seen its share of the domestic market fall by 2.4% over the year to September 2006. But increasing domestic competition has hit Jet too, with its market share falling from by 12.6% over the same period. Together however, the two airlines will have around a 37% domestic market share (after some domestic rationalisation).

Jet refutes comments that the deal was effectively forced upon it, for fear of losing the legal argument and having to face costly litigation and financial penalties, and insists that that not only does the deal shore up Jet’s domestic position, but that it also allows Jet to benefit from Air Sahara’s order for 10 737–800s, which are due for delivery in 2009–2011. Additionally, Jet says that Air Sahara traffic should feed into some of Jet’s international routes and — crucially — Jet will gain valuable slots for both domestic services (in 2006 the Indian government passed a law allowing slot transfers between merged airlines) and for international services, including some key Air Sahara slots at London Heathrow.

As the only other private Indian airline that has permission to fly internationally, Air Sahara operates to Colombo, Kathmandu and Singapore, had planned to launch a Delhi–London Heathrow route in July, and wanted to expand into other destinations, such as Guangzhou and Dhaka. However, Jet is to axe all of Air Sahara’s international services (some of which will be transferred to Jet) and rebrand and relaunch Sahara as JetLite in July, using it for domestic operations only. The intention is to use Air Sahara/JetLite as a "complement" to Jet Airways' domestic operation, with the rebranded airline positioned between full–service airlines and the swathe of domestic LCCs (though formally it will not be a LCC, as it will offer frills such as free in–flight catering and entertainment). Air Sahara currently has a fleet of 23 737s and CRJs, although the latter will be replaced by ATRs, Jet’s preferred short–haul aircraft.

Under a team parachuted in from Jet and led by Gary Kingshott, Jet’s chief commercial officer, JetLite will operate as a separate entity, and Goyal says his team will make JetLite profitable within a year, due to lower unit costs and synergies with Jet. At least Rs4bn ($90m) will be invested in "upgrading" Air Sahara as JetLite, including improvements in basic areas such as engineering support and maintenance, with Jet executives saying that Sahara’s maintenance standards are not as high as at Jet.

Financial stretch?

But there will be difficulties: Sahara’s pay and conditions are lower than at Jet, and Jet wants to keep salaries at those levels, while the culture of Sahara is described as "lax" by one analyst, and the integration of Sahara employees into Jet’s operational practices may lead to some staff departures. Although Air Sahara has a higher employee to aircraft ratio than Jet (see chart, page 16), pilots in particular are in short supply in India, and Jet has had to open a pilot training school in Brussels, which will train up to 200 pilots per year. How Air Sahara’s pilots will react to the takeover by Jet is hard to predict, as last year a number of Air Sahara’s pilots went on a "sick–out" in protest at the impending deal. Some analysts also believe JetLite will cannibalise Jet’s revenue, where around 20% of economy capacity is already offered at very low fares, but perhaps more of a concern is that the acquisition will stretch Jet financially. As of the end of 2006, Jet had debt of Rs53.4bn ($1.2bn), some 72% up on a year earlier, and in 2006 shareholders gave approval for the airline to raise up to $800m in equity and bonds in order to finance the acquisition of Air Sahara, improve the balance sheet and fund fleet purchases. This year Jet aims to raise $400m of that, but after initially talking with private equity companies, it now plans to raise the cash via a rights issue.

The cash raised will be used partly to pay for deposits on $3.7bn of new aircraft that Jet will receive over the next few years. Currently Jet’s fleet of 62 aircraft have an average age of just over five years (while Air Sahara’s 23–strong fleet have an average age of more than eight years), but between April this year and October 2008 Jet will take delivery of 20 widebodies. 10 777–300ERs are on order (with a further 10 on option), the first of which will arrive this June and with eight due to be delivered in 2007, while the first of 10 A330–200s arrived this April. Jet also has outstanding orders for 10 787s for delivery from 2011 onwards, although these are switchable for other Boeing models.

By March 2011, Jet (excluding Sahara) plans to have a fleet of 97 aircraft, and this new capacity will be used primarily to underpin a huge push on international routes, with Goyal aiming for revenue of $3bn-$4bn by 2012, with half of that from international routes.

Currently Jet operates to Colombo, Kathmandu, London Heathrow, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Bangkok (launched in January from Delhi and Kolkata, the former in competition with Air India, Indian Airlines and Thai Airways) using its fleet of 28 737–800s as well as five leased A330s and A340s but, as the widebodies arrive, routes into North America, Europe, Asia and Africa will be added.

The US is the prime target for Jet, although the launch of routes into the US has been delayed by a US State Department investigation into allegations that the finances of the airline and its chairman were linked to Dawood Ibrahim, an Indian–born terrorist suspect. Once the State Department found the allegations baseless, the US DoT gave approval at the end of 2006, and this May Jet unveiled plans for a European hub at Brussels airport, which it is setting up in partnership with Brussels Airlines. Starting in August, Jet will operate 777–300ERs on a route from Mumbai to Newark, stopping at Brussels, and later in the year it will add a daily Delhi–Brussels–Toronto service.

The medium–term goal is to build services up to 10 flights a day between India and North America via Brussels, and among the destinations that may be connected are Los Angeles, Chicago and New York in North America, and Delhi, Bangalore and Chennai in India. The link with Brussels Airlines entails adding Brussels' code to selected Jet flights, with Jet code–sharing on five Brussels' routes into Europe, which they aim to expand to 25 routes.

Elsewhere in Europe, and encouraged by liberalisation of the India–UK bilateral, Jet has plans for direct routes into the UK regions, most likely to commence with Birmingham. Jet currently operates to London Heathrow from Mumbai, Delhi, Amritsar, and Ahmedabad, most of which compete against Air India. Jet is also in talks with Lufthansa over co–operation on routes to Germany, with Munich the most likely destination, and is also negotiating with the German carrier on both a maintenance tie–up in India as well as a cargo venture, with Jet intending to launch a cargo subsidiary some time before the end of 2007.

As long–haul capacity increases, Jet will expand onto other destinations, such as South Africa, Kenya and Mauritius. A Mumbai to San Francisco via Shanghai route will launch at the end of 2007, also using 777–300ERs, while several routes will be launched into the Gulf in 2008, with likely destinations to include Dubai, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Doha.

On all these routes the new widebodies will incorporate revamped products in three classes (including first–class for the first time) on the 777s and two classes on the A330s. The 777s will include flat beds in an attempt to raise Jet’s first and business class products to the same standards as British Airways and Virgin Atlantic, and Jet’s focus on business travellers includes more than 1,300 deals with Indian–based corporates, which Jet wants to increase to 2,000 by March 2008. Jet also introduced a new booking engine for corporates and travel agents earlier this year, to complement existing distribution agreements with Indian travel portals such as Yatra.

Along with the push into intentional markets, in April Jet unveiled an updated livery and branding (designed by brand consultants Landor Associates), which will be used in a new marketing campaign being planned by agency M&C Saatchi (which won an account worth $11m in January, and is opening up an office in Mumbai to service Jet). And an indication of the growing rivalry with Air India came in March when Jet poached Perfect Relations — Air India’s PR company — which according to sources has deeply angered Air India executives.

Air India and Indian Airlines

Jet isn’t yet a member of a global alliance, but over the last year has expanded code–sharing to Qantas, Continental and United, and also has FFP partnerships with Air France and South African Airways. Wolfgang Prock–Schauer, Jet’s CEO, was previously head of alliances at Austrian Airlines, part of Star, and the Star alliance has said it would like Jet to join. However, Jet has so far not been drawn into any commitment, and both it and the global alliances will want to see how successful Jet’s costly international expansion will be before they commit to any partnership. Air India dates back to 1932, and launched its first international route in 1948. Today the international flag carrier operates from 14 Indian cities to 31 destinations around the world, the majority of which are in the Asia–Pacific (10 destinations) and Gulf regions (nine). The 100% state–owned airline has hubs at Mumbai and Delhi, and employs more than 15,000 staff. In the 2005/06 financial year, ending in March 2006, Air India posted revenue of Rs87.5bn ($1,971m), 15% up on the previous year, although net profit fell 82% to Rs163m ($3.7m), due largely to increasing competition and a 44% rise in fuel costs.

The underlying problem that Air India faces is that it just does not have the ability to compete with the private sector, and as a result its market share continues to fall. In an attempt to find a solution the Indian government finally approved, in March, the long–awaited merger of Air India and Indian Airlines, the 100% state–owned domestic carrier (which sometimes drops "Airlines" from its formal name for marketing purposes) that made an $11m net profit in 2005/06 (down by a quarter on 2004/05).

A merger has been on the government’s agenda for many years, but fierce resistance has come from unions and politicians, who feared substantial job losses. However, a ministerial panel appointed in 2006 to consider the merger decided in its favour in early 2007 (with — crucially — a recommendation that there should be no job losses at the merged airline, and no changes to pay and conditions), and formal government approval followed soon after, in March this year.

The government has an ambitious target of July 15th for the merger’s legal completion, although operational integration could take another two years to carry out. Although there will be no job losses, many analysts expect the merger will be slow and painful at times — particularly as the airlines have different networks, operational procedures and fleets — but it’s a process that the two airlines have to drive through if the state–owned entity wants to have any hope of survival against private competition. This includes domestic LCCs, full–service Jet Airways and foreign airlines on international routes, and this competition has already eroded the combined international/domestic market share of Air India and Indian from 81% to 21% in a decade (see chart, page 13).

The Indian government has chosen to keep "Air India" as the name for the merged airline, with Air India’s logo also retained (although the airline will have a new livery), and with its corporate headquarters in Mumbai (the base of Air India) rather than Delhi (where Indian is located). Following lots of speculation, the new chairman and "joint" managing director will be Vasudevan Thulasidas, who holds the same positions at Air India, while Vishwapati Trivedi, chairman and managing director of Indian, will also become a "joint" managing director. However, Thulasidas is due to retire in March 2008, and it is not yet clear whether Trivedi will replace him at that time, or whether someone new will take over.

The joint managing directors will have much to do, although they will have considerable support from the government, which is amending tax and finance laws so that Air India and Indian can carry forward past losses and unabsorbed depreciation into the merged entity, thereby providing a tax shield against future profits. The enlarged airline will also benefit from a waiver on stamp duty, and altogether these measures will save the merged airline around $171m.

Crucially though, the managing directors will have their hands tied in terms of cost–cutting. Air India currently employs 15,535 and Indian 19,300, and the combined workforce of around 35,000 fares badly when compared against its main rival, in terms of employees per aircraft (see chart, page 16). Under the terms of the merger these figures will not come down, with Air India insisting it will not even introduce a voluntary retirement scheme. Earlier this year Air India did cut the number of cabin crew on international flights, which many analysts had long criticised as being over–manned (e.g. Air India used 19 cabin crew on 747–400s as opposed to the 16 normally assigned by other airlines), but although Air India says this reduction in crew per aircraft will reduce costs by $11m per year, the "cut" staff have been reassigned elsewhere, so their costs will reappear elsewhere as well.

However, the merged airline will have separate "strategic business units" for full–service, cargo and LCC functions, as well as for functional business such as maintenance, ground handling and catering, and this will at least identify the areas that are the most overstaffed, so that action in the future may be slightly easier to implement. At the very least, when the airlines merge there should be substantial non–staff cost–savings made in the fields of maintenance and ground handling.

In terms of fleet size, the merged airline will become one of the top five carriers in Asia, with a combined fleet of 118 aircraft (see table, page 17), approximately a third of all aircraft registered with Indian carriers. More importantly, the two airlines have more than 100 aircraft on order, which is vital given that Air India’s fleet has an average age of more than 16 years (with its 16 A310s having an average of more than 20 years), while Indian has an average age of 14 years. Until recently Air India had not ordered aircraft for a decade (instead relying on expensive leased aircraft), and the need for urgent fleet renewal was highlighted in April when two Air India aircraft (an A310 and a 767) made emergency landings on the same day, with an Indian civil aviation official saying that "poor maintenance is the major cause behind the two incidents".

That’s why in early 2006 Air India placed the largest ever order by an Indian airline, for 68 Boeing aircraft with a list price of $11.6bn. Altogether 15 777–300ERs, 27 787s, 18 737- 800s (for Air India Express) and eight 777- 200LRs will be delivered by 2012. The first aircraft — a 737–800 — was received in December 2006 (becoming the first new aircraft to be delivered to Air India since 1996), while the first 777 is due to be delivered this June. Altogether 17 of the 50 long–haul aircraft on order will arrive by early 2008, and the rest will be delivered by 2010.

Pilot worries

These new aircraft will replace everything in the current fleet other than six owned 747- 400s (which will continue in service until at least 2014). Indian also placed an order for more than 40 Airbus aircraft in 2005, at a value of $2.2bn and for delivery by 2011, and did have plans to acquire up to 10 widebodies, although this will have to be confirmed now that the merger is going ahead. At the moment, with leased aircraft being phased out (around 60% of Air India and Indian’s fleet are currently leased), the merged airline plans to have a fleet of around 125 by 2010. Although the merged airline will receive an aircraft a month until 2011, a key problem will be to find enough pilots to fly this equipment. As of this April Air India had a pilot shortfall of around 120, and this is getting worse as the 737–800s arrive, with the airline estimating it needs another 100 pilots a year for the next seven years.

Although Air India will be helped by a new MoU signed with the Indian Air Force, which will release batches of retiring pilots (up to 20 strong at "regular intervals") in order to reduce the shortage, it is estimated that up to 3,000 new pilots will be needed in India over the next five years, and Indian flight training schools are already working at maximum capacity. Although the Indian government has steadily raised the pilot retirement age from 60 to 65 over the last few years, in 2005 it had to introduce a six month notice period for pilots in order to deter airlines from poaching staff from competitors, and Air India (and other Indian airlines) has no option but to recruit more foreign pilots. Unsurprisingly, the shortage is leading to significant pay rises for pilots at Air India and other airlines.

Air India first recruited from abroad back in 2004 and is now hiring pilots direct from Brazil and Serbia, as well as looking to training schools in the US and New Zealand for other pilot intakes. Indeed in November last year the pilot shortage became so acute that Air India was forced to wet lease a 767- 300ER for six months from Edinburgh–based Flyglobespan, prior to the arrival of the 777s this summer, and this April it also wet leased an A310 for a year from Czech airline CSA.

Despite this problem, the new widebody aircraft will be a vital boost to Air India, which has increased international capacity substantially over the last few years, particularly to the US and Europe. In North America Air India operates to New York JFK, Newark, Los Angeles, Chicago and Toronto, with more than 30 flights a week between the US and India. However, Air India faces increasing competition for a slice of the 1.5m passengers a year that travel on US–India routes. Delta, Continental and American all offer US–India services and are increasing flights (with Continental, for example, launching daily, non–stop Newark–Mumbai services this October), but Air India plans to fight back with the launch of services to Dallas, Houston and San Francisco by March 2009.

In Europe, Air India operates to London Heathrow, Paris CDG, Frankfurt and Birmingham, and the airline aims to develop at least one hub in Europe, in direct competition with the Brussels operation of Jet.

Currently, the biggest proportion of Air India’s revenue comes from the Asia and Middle East regions, and it is here that the merger with Indian will provide most benefit outside of India. Indian operates mediumhaul routes into the Gulf with narrowbodies, and — for example — on the India–Kuwait sector the government estimates the airlines will save $18m a year from rationalisation of flights. Similarly, the two airlines operate around 10 flights each day onto Singapore, but load factor is believed to be hovering around the 60% mark, and this will be another area for rationalisation.

Air India also has another long–haul network via Air India Express, its low cost subsidiary, which will merge with Alliance Air, Indian’s domestic LCC, once the two parents merge. Express is based in Mumbai and launched its first route in 2005, but with initial load factors in the 90s has expanded rapidly and currently operates from nine Indian cities to nine destinations a maximum four hours flying time away — Abu Dhabi, Al Ain, Dubai and Sharjah (all in the UAE); Muscat and Salalah in Oman; Bahrain, Doha and Singapore.

Express initially flew with leased 737- 800s, but with new capacity from the 737- 800s ordered by Air India, further routes will be launched later this year. Express will have a fleet of 25 aircraft by 2008 and also has ambitions to build up a route network outside of the Gulf region. Express’s first service outside of the Middle East was to Singapore, a five–times–a-week service launched in October last year from Chennai (and competing against Indian Airlines, Singapore and Jet), and this May Thulasidas said that low cost services to destinations further than Express’s current four–hour limit were also under consideration, with Asian cities such as Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok believed to be the initial targets. Express may also place an order for further 737- 800s, (for delivery in 2009 at the earliest), which according to T.P. Singh, COO of Express, "is not going to be a small order".

One major decision for the new Air India/Indian will be its choice of global alliance. Air India had been due to make a decision by the end of the year, but this is likely to be postponed until the merger is completed, when the new airline will be a lot more attractive to the alliances. SkyTeam and oneworld will be keen to sign–up the merged airline, particularly if Jet does go with Star, which would leave the alliance that Air India/Indian didn’t choose out of SkyTeam and oneworld with a significant gap in its route network and with no obvious means of filling it. But Air India has also been linked strongly with Star, thanks to Air India’s existing code–shares with Lufthansa and United, although informal negotiations are believed to be taking place between Air India executives and all three of the global alliances at present.

According to the Indian government, although the costs of integration are estimated at Rs2bn, the merger will improve profits by Rs6bn (£135m) in the third year after the merger. That’s an ambitious target for a state–owned entity where staff costs are "fixed", but a necessary one if the government wants to achieve its ambition of an IPO. Both airlines had been due to IPO in 2006, partly in order to finance new aircraft orders, but an IPO has been postponed until the merger is well underway, with 2008 now the earliest possible date.

At that date it is likely that the IPO will float only a minority stake of around 25% in Air India/Indian, with the government retaining a majority, but getting in non–governmental investors — no matter how small the initial stake — is crucial for the future of the merged airline for two reasons.

First, fresh financing is needed. Air India’s fleet expansion is being financed by a $7bn line of credit with ABN Amro, but interest on the merged companies' existing debt is already approaching $1bn per year, and at some point Air India will need to place an order for larger A380 or 747 models for delivery after 2012, and these aircraft will have to financed somehow.

Who will win?

Second — and perhaps more importantly — new investors are needed in order to shake up Air India/Indian’s management. Worryingly, Indian aviation minister Praful Patel says that though the merged airline may undergo an IPO, it would still remain what is termed a "public sector enterprise", and that in terms of hiring professional management: "I do not think businessmen are the only solution … I have been in government long enough to understand that there are excellent bureaucrats who can handle absolutely difficult situations." Both Jet/Sahara and Air India/Indian aim to become among the very best airlines in Asia by 2010 (and Goyal says he wants Jet to be among the top five carriers in the world in the next five years), but as they grow they will compete fiercely on international routes out of India.

They will also have to battle against foreign airlines and from competition closer to home. For example, Bangalore–based Kingfisher has five A380–800s and five A350s on order, and is putting intense pressure on the government to operate internationally. Kingfisher may get around the existing "five–year" requirement by using Kingfisher International, its US–based subsidiary, to operate non–stop routes such as Mumbai–New York and Bangalore–San Francisco in 2008. Other Indian airlines will follow Kingfisher’s example, and it’s entirely feasible that when the current 49% limit restriction on foreign investment in Indian airlines (with foreign airlines not allowed to invest at all) is eased, then aggressive foreign carriers may take direct stakes in expanding Indian airlines, which would present formidable extra competition to Air India and Jet.

In the short–term, however, the two airlines may be forgiven for focussing on making their mergers work. The key difference between the two airline blocks is efficiency — although in terms of ASKs per employee Air India appears more efficient than Jet (see chart, page 16), this is skewed by the higher average stage length at Air India, and by another measure — employees per aircraft — both Air India and Indian have higher ratios than Jet and Sahara (see chart, page 16). And while there have been recent managerial changes at Jet, some analysts believe that the management at Jet is far superior to that at Air India.

Nevertheless, the giant Air India/Indian block should not be underestimated, as the two airlines carried a combined 13.7m passengers in 2005/06 and, according to one analyst, control more than 70% of airport infrastructure at Delhi and Mumbai.

Jet says that with its planned expansion, it and JetLite will offer more destinations than Air India/Indian by 2008, and that it will operate them at a higher load factor than its main rival. However, Jet may be forgetting the continuing government support for Air India/India. The government is committed to a massive increase in investment in Air India/Indian in order to fund fleet expansion, with the official state "allocation" for Air India rising from $111m in 06/07 to $1.4bn in 07/08 and for Indian from $79m to $565m, and against that kind of ongoing support, Jet will do well to achieve its ambitions.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air India/Air India Express | |||

| A310 | 16 | ||

| 737-800 | 13 | 12 | |

| 747-300C | 2 | ||

| 747-400 | 8 | ||

| 747-400C | 1 | ||

| 777-200 | 1 | ||

| 777-200ER | 3 | ||

| 777-200LR | 8 | ||

| 777-300ER | 15 | ||

| 787-8 | 27 | ||

| Total | 44 | 62 | 0 |

| Indian | |||

| A300 | 3 | ||

| A319 | 6 | 20 | |

| A320 | 48 | 4 | |

| A321 | 20 | ||

| Dornier 228 | 2 | ||

| Total | 59 | 44 | 0 |

| Alliance Air | |||

| 737-200 | 11 | ||

| ATR-42 | 4 | ||

| Total | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Air India/Indian total | 118 | 106 | 0 |

| Jet Airways | |||

| A330-200 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| A340-300 | 3 | ||

| 737-400 | 6 | ||

| 737-700 | 13 | 2 | |

| 737-800 | 28 | 4 | |

| 737-900 | 2 | ||

| 777-300ER | 10 | 10 | |

| 787-8 | 10 | ||

| ATR 72-500 | 8 | ||

| Total | 62 | 36 | 20 |

| Air Sahara | |||

| 737-300 | 2 | ||

| 737-400 | 3 | ||

| 737-700 | 5 | ||

| 737-800 | 7 | 10 | |

| CRJ200 | 6 | ||

| Total | 23 | 10 | 0 |

| Jet/Sahara total | 85 | 46 | 20 |