US airlines: looming labour angst

June 2007

Despite the alarming rise in oil prices and weakening domestic demand in recent months, 2007 is still expected to be a strong year for the US legacy airline sector (see previous article). But there is another major threat on the longer–term horizon: rising labour costs.

Virtually every one of the concessionary labour contracts secured by the US legacy carriers in the past five years comes up for renegotiation in 2008- 2011. That and the many ominous new developments in the past two months indicate that labour costs will again be a major issue for the sector from mid–2008 onwards.

JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker predicted in a mid–April research note that industry labour costs would rise by $5bn annually in 2008–2010, warning that "airlines are living on borrowed time".

A $5bn hike in annual labour costs would have devastating profit implications. Baker pointed out that the industry has never produced an annual operating profit in excess of $8bn, though that was roughly what he was forecasting for 2007.

This raises the disturbing prospect that the boom could be short lived. Labour cost hikes would sharply reduce or eliminate industry profitability in the final years of the decade. In other words, 2006 and 2007 could end up being the peak profit years in the cycle.

Such a scenario would be disastrous given the US legacy carriers' enormous re–fleeting needs. The sector has only just returned to profitability. Pre–tax profit margins are still only in the low–single digits. Debt and pension burdens are substantial, as the balance sheet repair process has only just gotten under way.

Honeymoon over

At this point, 2008 industry earnings are still expected to show a modest improvement over this year’s earnings, which would make it three strong years in a row. However, Baker argued that the only legacy carriers likely to see profit improvement in 2008 are "those recently christened from bankruptcy who are still able to ring out a few more costs, offset by cost escalation at those carriers that navigated around the Chapter 11 process". Baker also suggested that, as 2007 wears on, "looming labour angst" would begin weighing on airline shares, starting with AMR. It has become very clear in recent months that the US airline industry’s post–September 11 honeymoon with labour is over. First, there has been a massive outcry about what the unions have called "executive greed" — unusually large top management stock awards or compensation packages at several major carriers, including AMR, UAL and Northwest. Angry airline employees all around the country have held protests and picketed or voiced objections at annual shareholder meetings.

Second, the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) has now officially adopted the position that the concessions negotiated by several carriers in bankruptcy since 2002 must be rolled back. ALPA said in April that it would seek to reopen contracts before amendable dates. This would mainly affect United, Delta and Northwest, which secured pilot contracts in Chapter 11 that become amendable between 2009 and 2011. US Airways has not yet succeeded in negotiating its initial post–merger pilot contract (and is now likely to find the process even tougher going).

Third, American’s pilots, represented by the independent Allied Pilots Association (APA), disclosed on May 3 that they are seeking a whopping 30.5% pay rate increase and a 15% signing bonus effective from May 2008, when their current contract becomes amendable, plus 5% annual rate increases thereafter. The initial 30.5% pay hike alone would restore the pilots' purchasing power to the pre–2003 levels. In other words, it would eliminate the bulk of the labour concessions that American secured on the courthouse steps in May 2003, which enabled it to avoid Chapter 11.

It is highly unusual for labour unions to go public with their opening proposals. APA’s decision to do so indicates that the stakes are high and that the union did not believe it would get what it wants through the normal negotiating process.

What happens at American will have critical industry implications, because APA is the first legacy pilot group to have a contract come up for renegotiation since the sector returned to profitability and because American’s pilots are already the highest paid among in the industry. The APA rates will establish a new benchmark on pilot pay.

All of American’s labour contracts become amendable in May 2008. The next in line will be Continental’s pilots and mechanics in late 2008, followed by all the other legacy labour groups from mid–2009.

United’s ALPA has already made its first move to reopen contract talks early. In a letter to CEO Glenn Tilton in late May, the pilots asked that negotiations with all of the UAL unions begin this August, with the goal of putting new contracts in place by February 2008 — nearly two years before the amendable dates.

The only legacy carriers that may enjoy slightly longer labour honeymoons are Delta and Northwest, simply because they are freshly out of bankruptcy. Delta has the advantage of currently excellent labour relations, reflecting the morale–boosting effect of fending off US Airways, a generous post–bankruptcy compensation programme, modest management pay and stock awards, etc. (see Aviation Strategy, April 2007).

Northwest has the advantage of not having any contracts become amendable until 2011, but it has an unhappy workforce. Its flight attendants ratified their concessionary contract narrowly and only two days before the company’s Chapter 11 exit. Calling the contract totally unacceptable, the flight attendants approved it just so that they could get their $182m equity claim — which, like the other Northwest unions, they planned to sell for cash.

Why the labour demands?

Pilot groups across the industry now appear committed to a common cause — a post–2001 development. There is more cooperation, such as twice–yearly conferences for North American pilot union officials. The latest of those, held in Dallas in early June, was co–hosted by American’s APA and Southwest’s independent pilot union SWAPA and it attracted 70 union officials from 16 airlines. According to APA, it is all "part of a concerted effort to reverse the damage inflicted on the pilot profession during the past several years". In recent years it has often been suggested that the post–September 11 era has dramatically changed the status of airline labour, reducing the power wielded by unions and permanently altering the negotiating balance in favour of management.

That is probably a fallacy. First, there has been no change to the labour law that would alter the negotiating balance. Second, labour costs have always been tied to the industry economic environment. In recent decades, airlines have managed to contain labour costs only in periods when they are losing money.

Third, this time around, there are two new issues that are making labour especially determined to get what they want: the massive concessions granted since 2002 and the growing differential between executive and worker pay.

Therefore labour is back with lofty demands, in the first place, because the US legacies' financial recovery is well established. The sector will post a healthy profit for the second year running in 2007, after heavy losses in 2001–2005. Thanks to minimal capital spending, the airlines are generating significant free cash flow — the highest in more than 20 years. Cash reserves are excellent, amounting to 20–30% of annual revenues. Airlines are not only meeting significant debt maturities but have started repaying debt ahead of schedule.

Ironically (since it is first in line for pilot contract amendment), American has been one of the industry’s strongest performers. Having turned around from a $677m net loss before special items in 2005 to a $330m profit in 2006, AMR is set to more than triple its earnings to $1.2bn in 2007. AMR also recently prepaid $364m of debt, which was in addition to this year’s $1.3bn scheduled debt payments. And the company was able to tap the public equity market in January, raising $500m through a common stock offering.

As final proof that industry recovery is firmly established, credit ratings have started inching up. Over the past winter, the three main rating agencies have all upgraded Continental’s and AMR’s ratings (Fitch in October 2006 and Moody’s in March). This spring, Moody’s also revised US Airways' outlook to "positive", while S&P made that move with AMR, indicating that upgrades were possible within a year.

APA and the other pilot unions have argued that the industry recovery has been much faster and stronger than the scenarios painted by the managements in bankruptcy courts and at the bargaining table. Certainly, it would seem that the balance sheet and credit rating improvements have materialised a little sooner than had been expected.

But the unions feel a great sense of urgency because it has been payback–time for airline executives and shareholders but not for the workers who have made enormous sacrifices since 2001.

According to Baker, US airlines have reduced their aggregate annual labour costs by $7bn since 2001, from $32bn to $25bn. The figures given by the unions are typically much larger because they often include pensions and are for multi–year periods.

In ALPA’s estimate, its 60,000 members have given $5bn in concessions in the past five years. Some pilots lost as much as 50% of their income and retirement benefits.

American’s APA provided $660m in givebacks in each of the past four years, for a total of $2.6bn worth of concessions. The pilots accepted immediate 20–50% pay cuts as part of the 2003 restructuring, and nearly 3,000 lost their jobs. Since then the pilots have received meagre 1.5% annual pay increases on top of a one–time 6% increase.

The APA givebacks were part of $1.8bn of annual wage, benefit and work rule concessions, amounting to $7.2bn over four years, granted by American’s workforce in 2003. The management also made sacrifices; at the top, newly appointed CEO Gerard Arpey kept his previous president/COO’s salary and declined to accept stock options that year. "Shared sacrifice" was the mantra heard from the leadership.

American’s unions were therefore dismayed when in April the company paid special bonuses worth $160m–plus to nearly 900 executives and managers. The awards, which were in stock that could be sold immediately, were part of the company’s long–term incentive plan. The payments were based on stock performance in 2004–2006 (AMR’s share price soared from $5 in May 2003 to $41 in January 2007, though it has since fallen steadily to the mid–20s).

CEO Arpey has accepted large bonuses for the past two years. It was disclosed in April that his 2007 compensation would amount to $6.6m. In 2006 Arpey earned $5.4m, of which $4.8m was stock and option awards.

The unions are angry about what they call "extremely disparate rate of financial recovery" between executives and front–line employees. They say that executive pay has risen at a compounded annual rate of more than 80% since the 2003 restructuring. The workers are also upset that bonuses were paid not just to the top officers but to a broad spectrum of management, while rank and file continues to work under concessionary contracts.

APA’s pay demands came within weeks of the bonuses being announced. The union observed that "other stakeholders have already recovered their investment in American’s turnaround".

Executive pay is also an issue at United and Northwest. United’s unions were enraged at the news in March that CEO Glenn Tilton earned $39.7m in 2006, mostly from stock and stock options. Tilton’s and other top executive compensation packages were approved and well–publicised when UAL emerged from Chapter 11 in February 2006, but ALPA argues that they "violate the concept of shared sacrifice/shared reward that all employees expected after the turmoil of bankruptcy".

The awards seem excessive also when considering that UAL has under–performed the industry, posting losses for the past two quarters. The share price, at around $35 in early June, is only slightly above the level it started trading in early 2006.

At Northwest, employees are extremely unhappy about the executive compensation packages approved by the bankruptcy court. The company’s top 400 executives and managers were granted 4.9% of the new equity over four years, worth $300m at the initial share price. The awards are in the form of restricted stock and stock options and will only have value if the business plan targets are achieved and the stock price appreciates.

CEO Doug Steenland’s share of the stock awards was estimated at $26.6m (over four years). In contrast, flight attendant pay at Northwest tops at $35,400 a year, down from $44,200 before Chapter 11. Northwest employees granted $1.4bn worth of annual concessions, with pilots taking 40% pay cuts.

In contrast with United, Northwest is actually now among the most profitable US airlines, earning the highest pre–tax margin among the legacies in the first quarter (around 2%). The bankruptcy court rejected the flight attendants' request to have their pay cuts reconsidered in light of the company’s speedy financial recovery; however, if Northwest continues to outperform the industry, the workers will not wait until 2011 to seek to have their pay restored.

Northwest has said that it hopes to share with employees more than $1bn in unsecured claims and profit sharing payments through 2010 (also, 4,800 employees below the top 400 received 0.6% of the new equity in the form of restricted stock vesting in a year, valued at $46.4m). The problem is that those payments will nowhere near make up for the concessions. The unsecured claim obtained by the flight attendants, for example, amounts to only around $15,000 per worker. The 2006 company–wide profit sharing payment in March was $32.6m, averaging about $1,000 per employee.

The math doesn't work

The other legacy carriers' profit sharing payouts have been equally modest, though Continental forked out a slightly more impressive $111m in March. Of course, AMR employees have not yet received any profit sharing, though payouts are likely based on the 2007 profits. APA estimates that the pay rate increases it is seeking, which would average 17% annually over the proposed three–year contract, would cost AMR $450m annually, plus $400m for the initial signing bonus. The impact would be to effectively wipe out profits, given that American’s other labour groups would demand similar increases. "We don’t see how the math works", commented Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg in a research note in early May.

JP Morgan’s Baker predicted in April (before APA’s announcement) that AMR’s per–share earnings could fall by 29% to $2.37 in 2008 (based on $700m or 10% higher labour costs in the second half of 2008). Currently, the consensus forecast for AMR for 2008 is still $4.11, indicating that most analysts no not assume any labour cost impact at all (the estimates range from $2.07 to $5.50).

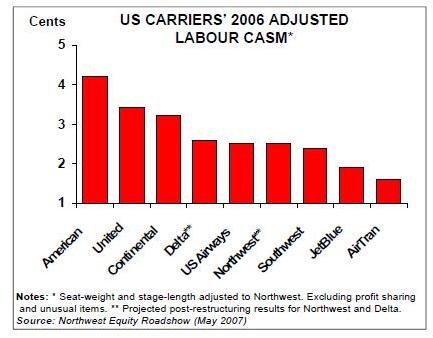

The problem is that American already has a labour cost disadvantage compared to the four legacies that were in bankruptcy (see chart, left). Because of that, American is targeting $300m additional savings in 2007 through areas such as distribution, scheduling, fleet enhancements and fuel conservation (though it has to be said that nearly all of the US airlines continue to be in a cost–cutting mode).

Also, American needs to continue to de–leverage itself because it is in desperate need of re–fleeting. Even though its debt and lease obligations have declined by $2.2bn in the past year, they were still a substantial $17.5bn at the end of March. AMR’s adjusted debt–to–capital ratio is still 98%, its credit ratings are five notches below investment grade, and it has a heavy pension burden.

American has a relatively old fleet, averaging 13.9 years in age at the end of March. The main challenge is replacing 300 MD–80s (average age over 17 years), which account for nearly half of the fleet. The process began in March, when American pulled forward deliveries of 47 737–800s to the 2009–2012 timeframe — possible because of its flexible long–term purchase contract with Boeing. Replacing all the MD–80s with 737s would require an investment of almost $10bn.

The other legacy carriers also have a substantial burden of debt and leases — even Delta and Northwest, despite their recent Chapter 11 visits (reasons: most of their debt was secured, and they did not downsize significantly). However, there is more variation in re–fleeting needs.

The best positioned of the legacy carriers is Continental, which continued to take deliveries through the post–2001 crisis and has an average fleet age of only 10 years. Delta and United are also reasonably well positioned because they reshuffled or restructured their fleets in bankruptcy; they have aging aircraft but do not absolutely need to make fleet decisions for several years.

Northwest has the oldest fleet, averaging 18 years in age, and needs to start replacing 69 DC–9s that are at least 25 years old. The airline is fortunate to have firm orders in place for 18 787s, plus 50 options, for delivery from August 2008. Financing all those aircraft will be a challenge and will stretch an already heavily leveraged balance sheet, but at least the bulk of the spending should be out of the way by the time labour cost pressures build. Northwest’s CFO David Davis estimated recently that aircraft spending would peak at $1.8bn in 2008 and then fall in 2009–2010.

US Airways has older 737s and 757s that need replacing, and the airline has been in talks with Airbus and Boeing about ordering around 60 aircraft. CFO Derek Kerr said at the recent Merrill Lynch conference that the company expects to announce its long–haul aircraft choice (either the A350 or the 787) by the end of June.

According to a recent Boeing analysis using Airclaims data, published in the Wall Street Journal, the US major carriers have 126 aircraft that are 25- 40 years old. Without new orders, that number would grow to 384 aircraft by 2012 and 840 by 2015. Therefore, the airlines need to start placing orders in 2007–2008 to avoid a crisis later on.

The ordering got delayed as the airlines waited for financial stability and Boeing and Airbus to develop new–generation narrowbody aircraft. There will not be any mad rush now, because production lines are full until 2011 and next–generation aircraft may not be ready until 2014 or beyond. Also, the industry can be expected to continue to exercise financial restraint until profit margins and balance sheets improve.

American’s CFO Tom Horton cautioned in recent speeches that airlines need to be very careful about allocating further capital until they can be certain that they can get a return on that capital. Perhaps American and other carriers could tie the new aircraft orders to getting reasonable labour agreements.

One way forward on the labour front would be to tie pay increases to productivity improvements, as in the past. However, APA is structuring its proposals so as to minimise such chances; it plans to present separate proposals later for variable compensation, because the pilots are determined not to trade off work–rule changes for pay restoration.

APA’s argument that the industry can simply offset higher labour costs by raising ticket prices is not realistic. It was possible in the late 1990s but much less so in the post–2001 environment (especially now that domestic demand is weakening).

Executive compensation issue

Pay demands like APA’s are totally out of line with the "reformed legacy carrier" cost structure that is emerging in response to the growth of LCCs. The industry is profitable only because it shed $7bn from its labour cost structure post–2001. The legacy carriers cannot afford to add back $5bn of those costs, as Baker’s scenario envisages. The executive stock awards granted by the airlines are all perfectly legitimate and proper. They are part of long–running compensation plans that were approved by boards and, in the case of Chapter 11 carriers, also by creditor committees and bankruptcy courts. Labour unions typically sat on the creditor committees.

Such awards are standard practice at large US companies, where a substantial portion of top executive pay is typically tied to company performance and is therefore at risk. Sometimes the risk pays off, as was the case when industry recovery prompted an extended rally in airline shares.

By contrast, rank and file at airlines prefer guaranteed compensation. According to ALPA, pilots want reasonable base wages (the practice at Southwest, for example), though they are also interested in stock on top of solid base wages. Several airlines, including United and American, have made the point that their unions turned down opportunities to link more member compensation to stock or buy stock at a special low price. But the reason is obvious: when a person’s base pay is at a very low level (like the $35,400 top annual flight attendant pay at Northwest), the bulk of it goes to pay the mortgage and necessary living expenses and therefore it cannot be at risk.

Like other companies, the major airlines feel that they need to offer competitive compensation packages in order to attract and retain top–tier management. Recent years have seen many top airline executives attain equally or better–paying positions outside the industry. For example, AMR’s former CEO Don Carty is now CFO of Dell and former CFO James Beer is now CFO of Symantec.

In contrast, employment trends for rank and file airline workers have been negative. The industry’s financial losses and restructuring have weakened employees' negotiating position. Also, because of seniority, groups such as pilots have few, if any, other employment opportunities unless they are prepared to accept substantial pay cuts.

Several analysts have suggested in recent months that labour should accept this new market reality. Merrill Lynch’s Linenberg argued that, as the world has become a harsher place for airlines, with the industry earning only 1–3% pre–tax margins even though this may be the cyclical peak, compensation for airline employees "may have been permanently altered" and therefore "pay restoration may be an unrealistic goal in light of the industry change". Linenberg noted that this is not unique to airline employees; for example, medical professionals' compensation fell dramatically as HMOs (a form of health insurance) proliferated in the US.

UBS' Sam Buttrick called the widening executive- worker pay differentials "simply a resetting of market rates". He criticised labour for thinking that the former market rates reflect "some level of birthright".

Executive pay has surged in most US companies in recent years (to a level many people consider unjustifiable, regardless of an individual’s leadership skills), and so has the gap between executive and worker pay. Because of the growing popularity of stock awards, the gap has widened when the stock market has risen and will obviously narrow when equity prices fall.

However, the situation with airlines is quite unique and there are unresolved issues. In other industries, labour has not made such enormous sacrifices to keep their companies afloat and employees are better paid.

The worst thing about the recent executive stock awards is that they are, as one Northwest lawyer put it, "out of spirit of any notion of shared sacrifice". The awards at American make mockery of the "pull together, win together" slogan used by the management and the highly successful "working together" initiative (collaboration between management and labour) that has led to significant additional cost savings and revenue enhancements in recent years.

In other words, by accepting the stock awards, the top executives are conforming to the letter of the law but not the spirit of the law.

At AMR’s annual shareholder meeting in May, APA proposed a so–called "say on pay" resolution — a vehicle for shareholders to voice approval or disapproval of executive compensation on an annual basis. The proposal was rejected, with many investors praising CEO Arpey for the significant achievement of keeping AMR out of bankruptcy and rebuilding its market value (which, of course, he deserved). However, the proposal got 38% of the vote and may well be adopted in the future. "Say on pay" has gained popularity in the US this year, after being recently authorised in a House bill. It was on the agendas of numerous AGMs this spring; in many cases it was defeated, but some large companies have adopted the rule voluntarily. There is talk that it could become widespread next year.

"Say on pay" would be a useful vehicle for monitoring executive pay on an ongoing basis, enabling investors to weigh in on what is reasonable as industry conditions and the company’s circumstances change. It would be advisory only, but a vote of disapproval would obviously put much pressure on top executives to decline stock awards that particular year.

Delta’s outgoing CEO Gerry Grinstein refused a Chapter 11 exit bonus, and officers and directors there will not receive pay increases until front–line employees have reached industry standard pay. In addition, Delta distributed $350m worth of stock and $130m in cash lump sum payments to 39,000 ordinary employees, which was in addition to the benefits secured by members of two unions as part of their concessionary new contracts. Given how inflammatory the executive stock awards have been with labour at the other legacy carriers, and in light of the earlier "shared sacrifice/shared reward" promises, it is frankly surprising that other legacy airline CEOs have not followed Grinstein’s lead.

By accepting the stock awards, American’s management effectively made the commitment to work with unions to negotiate contracts that workers will find acceptable. At the AGM, Arpey made promises to that effect. The problem is that American cannot afford to restore pay, so it is hard to see how this could be resolved.

If American and the other legacy carriers get away without restoring pay, it would further weaken morale and possibly even lead to a labour shortage. According to recent articles in the Wall Street Journal, airlines are having trouble retaining and hiring qualified workers especially in expensive locations such as the Northeast. Low pay, reduced retirement benefits, increased stress and loss of prestige and fun — the WSJ called many airline jobs now "more akin to those at a fast–food restaurant" — have led to airline workers starting over with new careers.

Reduced staffing levels, less experienced workers and weakened morale could have serious ramifications for service levels and punctuality, reducing productivity at peak times and ultimately hurting the bottom line.

Even if there are no strikes or work slowdowns (none are currently on the cards), unhappy workers mean a lack of goodwill. American recently found that out the hard way: it had to withdraw its Dallas–Beijing route application after its pilots refused to sign a deal allowing them to work the longer hours necessary on that route.