JetBlue: trendsetter faces new challenges

June 2005

JetBlue Airways is one of only three US airlines outside the regional sector to have remained profitable in the current high fuel–cost environment (the others are Southwest and AirTran), but its profit margins have slipped significantly in the past 12 months or so. While continuing to grow rapidly with A320 operations, New York City’s low–fare carrier faces the additional challenge of integrating a second aircraft type, the 100–seat ERJ–190, to its fleet this autumn, in a bid to expand into smaller markets.

How will JetBlue deal with these challenges, while also taking advantage of new opportunities arising from industry consolidation? Are double–digit operating margins a thing of the past?

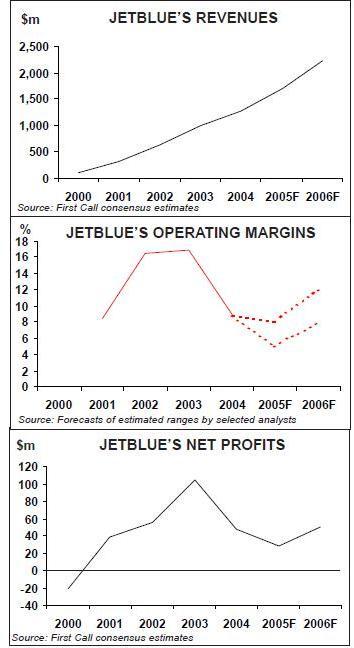

JetBlue, which commenced operations from New York JFK in February 2000, has been a huge success both financially and in the marketplace. It had perfect credentials — ample start–up funds, a strong management team and a promising growth niche. It has succeeded in attaining Southwest’s efficiency levels, despite its high–cost Northeast environment, a much smaller fleet and a more up–market product. JetBlue became profitable after only six months of operation and went on to achieve spectacular 17% operating margins in 2002 and 2003.

With its new A320 fleet, state–of–the–art technology and superior in–flight product, JetBlue has also set new standards in service quality. There is evidence that, like Southwest, it has built a "cult following", which has enabled it to attract price premiums and considerable customer loyalty.

On top of all that, JetBlue has grown extremely rapidly. It achieved "major carrier" status, with $1bn–plus annual revenues, in 2004 — its fifth year of operation, which is by far the fastest–track to a major ever achieved by a US airline.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that JetBlue has become a trendsetter or role model for LCC hopefuls around the world, much like Southwest has traditionally been. Both airlines' progress and strategic moves are followed with keen interest in all corners of the globe.

It has been disappointing to see JetBlue’s financial results deteriorate sharply since early 2004, particularly since Southwest’s earnings have shown characteristically little variation. But the reason for the discrepancy is simple: of the US airlines, only Southwest happened to have adequate fuel hedges in place to protect against the past 12 months' surge in fuel prices. Last year, JetBlue’s operating margin plummeted by eight percentage points to 8.9% and net income halved to $47.5m.

To keep things in perspective, JetBlue has demonstrated that it can remain profitable in the most dismal of industry conditions and while also continuing to grow rapidly. Its 2004 operating margin was still slightly higher than Southwest’s (8.5%).

Also, JetBlue’s extremely strong liquidity position gives it considerable staying power. After raising $243m through a convertible debt offering in March, the airline had $652m in cash at the end of the first quarter. That was about 50% of last year’s revenues, compared to the industry average of about 23%.

However, debt has built up due to aircraft purchases — total debt was $1.9bn and adjusted debt–to–capital ratio 76% at the end of March — so JetBlue will need to generate cash in the future.

JetBlue’s ability to do a convertible offering in the current environment obviously reflected investor confidence in its prospects. Also, many analysts continue to recommend the stock as a "buy", arguing that P/E ratios as high as 37–50 times 2006 estimated earnings (compared to 24–34 times for other LCCs) can be justified on the basis of JetBlue’s general earnings potential and because it is a "higher–profile sector leader".

That said, investors obviously want to know what JetBlue is doing to get back on the track to reach its full earnings potential.With fuel costs being hard to forecast, what are the trends for non–fuel unit costs? And are JetBlue’s revenues benefiting from the industry fare increases?

Other pertinent questions concern JetBlue’s ambitious growth strategy. What exactly does it plan to do with the ERJ- 190s? Will it not soon run out of good markets for the A320s? What impact might a US Airways–America West merger have on JetBlue?

Cost and revenue outlook

Lastly, with other prominent LCCs like Southwest and AWA having grabbed opportunities to participate in industry restructuring, what is JetBlue’s position on that subject? JetBlue has hedged roughly 20% of its fuel requirements in April–December 2005 in the form of crude oil swaps at just under $30 per barrel. This is down from 26% in the first quarter and 47% in the fourth quarter.

JetBlue is therefore in a better position that most other large US airlines, which typically have single–digit or no hedging coverage at all this year. However, JetBlue is nowhere near Southwest’s hedge position (85% of 2005 fuel needs at $26), and it does not have any hedges in place for 2006.

With fuel now accounting for 25% of JetBlue’s total operating costs, this year’s profit performance will largely depend on fuel price movements. In its latest earnings guidance, issued in late April, the company predicted that its operating margin would decline to 5–7% in 2005 (from 8.9% in 2004), based on an average fuel price assumption of $1.45 per gallon. However, that was widely regarded as the worst–case scenario, and many analysts are currently predicting an operating margin in the region of 8% in 2005.

The current First Call consensus forecast (average of 11 analysts' estimates) is that JetBlue’s EPS, which fell from 85 cents in 2003 to 43 cents in 2004, will decline further to 26 cents in 2005, before recovering back to 43 cents in 2006. But the range in estimates is extremely wide, illustrating the difficulty of forecasting airline earnings at present.

On a fuel–neutral basis, JetBlue’s financial performance has certainly improved. Its first–quarter operating margin would have been 12.7% (up slightly on the year–earlier 11.3%), rather than the actual 6.9%. Its unit costs (CASM) would have risen by just 4%, rather than the actual 11%.

However, even including fuel, JetBlue’s CASM is still remarkably low, at 6.10 cents per ASM in 2004 or an estimated 6.60–6.70 cents in 2005. This is partly because its average stage length rose from 986 miles in 2001 to around 1,300 miles in 2003 (the cur–rent level). On a stage–length adjusted basis, JetBlue’s CASM is higher than Southwest’s. Significantly, however, JetBlue has been able to compensate for the inevitable increase in its maintenance and sales/marketing unit costs by becoming more efficient. Its average daily aircraft utilisation has risen steadily, reaching 13 hours in 2003 and 13.4 hours in 2004. Airbus recently recognised JetBlue as the A320 operator with the best dispatch reliability and highest utilisation.

Rather surprisingly, JetBlue’s financial analyses in 2003 suggested that the ERJ- 190 would generate profit margins that are comparable or better than those achieved with the A320. The ERJ–190 is expected to have a one–cent CASM premium over the A320 on comparable stage lengths, but the airline is confident that it will be able to compensate for that on the revenue side.

Last summer JetBlue established highly attractive pilot rates for the ERJ–190. In JPMorgan analyst Jamie Baker’s calculations, ERJ–190 senior captain pay per seat will be just 10% above JetBlue’s A320s.

Baker also suggested that despite its smaller size, the ERJ–190 would offer better cockpit/ seat economics than larger Frontier A319s, AirTran 717s and Southwest 737s.

Regarding recent developments on the revenue side, JetBlue has benefited from two things. First, there has been some rationalisation of capacity in transcontinental markets, which helped raise JetBlue’s total unit revenues (RASM) by 5.7% in the first quarter. Its load factor rose by 5.9 points to 85.8% — probably the highest in the industry.

Second, the airline has implemented two broad $5 one–way fare increases since mid- March, which will help boost its RASM in the remainder of this year.

The transcontinental capacity reductions this past winter were the result of AWA exiting key markets, American pulling out of Long Beach and cutting frequencies elsewhere, United and Delta cutting services and JetBlue also reducing frequencies.

All of that was highly significant for JetBlue, which operates 48% of its capacity in the coast–to coast markets and has been losing money there in the past 12 months or so.

The airline said that the routes were still unprofitable in the first quarter but that the trends were encouraging.

JetBlue is also expected to benefit from a reduction in industry capacity on the East Coast this year. It is too early to estimate how extensive the changes will be (whether Independence Air will disappear, for example), but some analysts are already predicting that higher East Coast fares will help JetBlue return to operating margins in the low double–digits next year.

Ambitious growth plans

JetBlue is set to continue to grow extremely rapidly, adding typically 17–18 A320s and 18 ERJ–190s to its fleet annually over the next 6–7 years. At the end of March, the airline operated 73 A320s, of which 48 were owned and 25 were under operating leases. The firm order book included 110 A320s and 100 ERJ–190s, all for delivery in 2005–2011. Options included 50 A320s (2008–2013 delivery) and 100 ERJ–190s (2011–2016 delivery). If all of the current firm orders and options were taken, JetBlue’s fleet would grow to 433 aircraft by 2016.

This year JetBlue is taking 15 A320s (including four delivered in the first quarter) and the first seven ERJ–190s. The ERJ–190 is expected to enter service in October or November, which means that it will have only negligible capacity or revenue impact in 2005. This year’s overall ASM growth is estimated to be 26–28%.

JetBlue currently operates 293 flights a day, serving 31 destinations in 13 states, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic and the Bahamas. In addition to JFK, it operates a smaller hub at Long Beach (California) and is also developing Boston into a focus city.

The latest additions, in May, included Burbank (as its seventh city in California), Portland (Oregon) and Ponce (its third city in Puerto Rico). Last month the airline also continued its "connect the dots" strategy by adding service from Boston to Las Vegas and San Jose and from Washington/Dulles to San Diego.

One of JetBlue’s key strengths is that it has built leading positions in both New York–Florida and New York–California markets.

Like Southwest, it dominates its most important markets — something that may prove particularly important in the new domestic fare environment.

Of course, the downside of that strategy for a relatively small carrier (in the past year at least) has been heavy exposure to the two most competitive domestic markets — transcontinental and the East Coast.

In the first quarter, east–west and New York–Florida accounted for 48% and 41% of JetBlue’s total ASMs, with the Caribbean accounting for 6% and short–haul in the Northeast and in the West 5%. By comparison, much larger Southwest has benefited from its more diversified network, which includes extensive operations in the West.

JetBlue has introduced some novel strategies to minimise competitive exposure.

In the Los Angeles area, its strategy has been to avoid LAX, the main airport that is served from New York by five different airlines with 39 daily nonstop flights but which only accounts for 36% of the LA area traffic.

Instead, JetBlue’s strategy is to surround the area with a total of 14 daily flights to other airports (Long Beach, Ontario and Burbank), which together account for 64% of the LA area traffic.

At the same time, JetBlue is flexible enough to enter the most competitive and congested hubs if it helps cement market position. In September 2004 it began serving its largest market, Fort Lauderdale, also from New York LaGuardia, supplementing its 12 daily flights from JFK with seven additional flights from LaGuardia. It will consider serving a couple of other Florida cities from LaGuardia if more slots become available.

Earlier this year JetBlue signed a long term agreement to occupy an 11–gate facility at Boston’s Logan International Airport.

This will facilitate major growth from that city over the next three years. The current schedule, introduced in May, includes 19 daily flights from Boston to various Florida and West Coast destinations, utilising five gates. JetBlue also expects to continue to grow from Washington/Dulles.

One would think that, in this environment of excess industry capacity, rapid LCC growth and fierce competition between legacies and LCCs, there might soon be a shortage of good growth markets for LCCs to enter. However, that is clearly not the case with JetBlue, in part because JFK, where the airline has a 43% passenger share, is a uniquely attractive major market and in part because JetBlue is prepared to enter into smaller hub markets (hence the ERJ–190 decision). The latter contrasts with the typical LCC strategy, pioneered by Southwest, of sticking to large point–to–point markets and leaving smaller hub markets to legacy carriers.

JetBlue’s CEO David Neeleman has repeatedly stressed that there continue to be plenty of exciting things for JetBlue to do with the A320s. In a recent conference call he pointed out that because Florida has been a priority and is "eating up" so many aircraft, the airline has not been able to serve many destinations that it would have liked to add earlier. The most obvious areas are the Mid–Atlantic and the Midwest — blank spaces on the route map.

Likewise, JetBlue will have a hard time deciding where to put the ERJ–190s. Its initial analyses in 2003 identified almost 900 potential markets that were suitable for the ERJ–190 (with daily volumes of 200–500 one–way passengers) and did not yet benefit from low fares.

Like regional jets, the ERJ–190 will be used for multiple purposes — to develop new markets, maintain frequencies in existing markets in the off–peak, operate seasonal service, etc. The airline has frequently mentioned Richmond (Virginia) as one potential new market that could be tripled with lower fares. Many of the Florida markets, which experience sharp seasonal shifts in demand, are probably good candidates for ERJ–190 seasonal service.

With the ERJ–190s, JetBlue is obviously positioning itself for more head–to–head confrontation with competitors' RJs. It was attracted to the aircraft type by what it earlier called "artificial economy in the sizes of aircraft" created by scope clauses. The 100- seaters flying 11 hours a day will have a huge efficiency advantage over competitors' 50–seat RJs flying typically eight hours a day. Although future scope clauses will include larger RJs, JetBlue feels that the trend is so gradual that it will retain a competitive advantage for many years to come.v Neeleman was asked at Merrill Lynch’s recent transportation conference if he was concerned about the relaxation of scope clauses at AWA and US Airways, which allow larger RJs, and those airlines' plans to target Boston, New York and Washington. Neeleman said that he was not particularly concerned, first, because there are "hundreds of markets" where the ERJ–190 can go. Second, the ERJ–190’s range (2,100 miles) is longer than the RJs', enabling it to serve some markets that RJs cannot reach. Third, JetBlue will have a much better product.

However, Neeleman conceded that any significant future competitive moves from AWA/US Airways could influence the order in which ERJ–190 markets are introduced.

The key premise with JetBlue’s new strategy is that the ERJ–190 is a rather unique new aircraft, both in terms of passenger comfort and operating economics. It apparently has the look and feel of a small jet and can offer the same comforts as JetBlue’s A320s. Maintaining what the company described as "the JetBlue experience" was a key requirement (see Aviation Strategy’s analysis of JetBlue’s ERJ–190 decision in the July 2003 issue).

Getting investment priorities right

JetBlue may have the industry’s best cash position but it also has significant capital spending requirements, due to its aggressive fleet expansion and a host of infrastructure projects. Its committed capital expenditures will run at $1.1–1.3bn annually over the next few years.

However, there is no need to raise funds in the near term, because all significant near–term investments already have finance in place. All of this year’s A320 deliveries were pre–funded with an EETC in November 2004. GE Capital has committed to sale–leasebacks on the first 30 ERJ–190s, which covers deliveries through the first quarter of 2007.

JetBlue is wise to invest in new infrastructure facilities that will help it manage growth and ensure smooth integration of the ERJ–190. Over the past month or so, it has completed three major construction projects — a 140,000–square–foot hangar and maintenance facility at JFK, a 100,000–square–foot hangar and LiveTV installation facility at Orlando International Airport and a state–of the- art training and support facility also at Orlando.

In early June the airline was also close to signing a deal with the airport operator to jointly build a new $850m, 26–gate terminal at JFK. Construction is expected to begin late this year, for completion in mid–2008. Under an interim agreement, JetBlue is able to add seven temporary gates to the 13 it already has, to facilitate growth in the next couple of years.

JetBlue has indicated that it completed the convertible offering in March in part to have sufficient funds to acquire desirable assets that could become available through liquidations. However, JetBlue is mainly interested in gates and slots, not aircraft or people. As Neeleman recently put it: "We have the cash to be able to do some things but not merge with another airline — that is out of the question for us".

At the Merrill Lynch conference, Neeleman acknowledged that, with so much already on its plate in terms of growth and fleet additions, JetBlue was not quite ready at this point to take advantage of opportunities arising from industry consolidation. Had US Airways gone out of business now, it would have created much pressure on JetBlue to bid for the assets, so there was some relief in the JetBlue camp that US Airways found a rescuer.