European charter airlines: Adapting to a declining market

June 2005

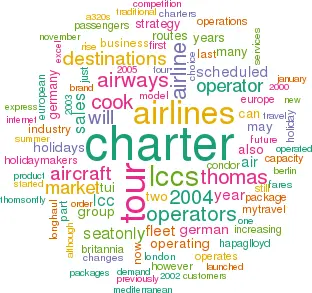

With the decline of the package holiday and the rise of the LCCs, the death of the charter carrier — long predicted by many in the industry — now seems closer than ever.

Yet charter airlines continue to insist they can survive the mounting challenges. Which view is right?

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council, residents of Germany and the UK — the two most important outbound charter markets in Europe — will continue to provide the third and fourth–largest expenditure on personal travel and tourism globally in 2005 ($196bn and $195bn respectively). However, the proportion of this that is spent on package holidays continues to decline, and there’s little doubt that this market — also known as air–inclusive tours, or AIT — is shrinking.

IACA (the industry association for charter airlines) say that whereas 100m Europeans took a package holiday in 2000, this had fallen to 90m by 2003. The greater sophistication of holidaymakers combined with the ability to book airline seats and hotels direct — thus bypassing the necessity for travel agents — underpins this trend, and puts even greater pressure on the traditionally thin margins of the tour operators.

But — and it’s an important but — there continues to be a healthy market for package holidays.

It may be declining and it may not be hugely profitable, but it is still a very large market, and one that many airlines, both charter and non–charter, are eager to serve.

Structural changes

Before analysing the future for charter airlines, it’s necessary to take a brief look at the structural changes that have taken place in the tour operating industry over the last decade. In the mid and late 1990s, many of Europe’s major tour operators went on acquisition frenzy after coming to the view that vertical integration was the only business model to have. This stemmed from an analysis that there was a limited supply of key product that holidaymakers wanted — and that the winning tour operators would be those companies that locked in the most popular destinations through hotels, airlift etc.

Back in August 1998, Aviation Strategy analysed the future of the European charter industry, and argued that four factors helped to insulate charter airlines from scheduled competition: European tourism flows; vertical integration in the tour operating industry; differences between the charter and scheduled products; and differences in charter and scheduled fleets.

These protective factors, however, began to unravel over the next few years:

- Although tourism flows have not changed greatly in the last few years — the annual north to south Europe summer holiday migration still takes place — there is a slow but steady leakage of former Mediterranean–destined holidaymakers to other medium- and long–haul destinations during the summer months.

- Falling consumer confidence in some European countries in the early 2000s — greatly exacerbated by September 11 — led to reduced demand for the AIT product. This put tremendous pressure on businesses with large amounts of costly fixed assets bought during the vertical integration boom of the 1990s. Interest payments on the debt that funded those tour operator acquisitions became a huge burden, and led not only to a re–examination of the vertical integration strategy, but also to a challenge to the continued existence of the heavily leveraged tour operators.

- The difference in product specs between the charter and scheduled product still exists, but is now a liability for the charter industry, rather than a protective barrier. The traditional package holiday was supply–driven, not demand led, and many holidaymakers are no longer satisfied with the traditional 7–day and 14–day "one–size–fits–all" packages that leave airports at three in the morning.

The internet and the ability to book individual elements of the package as part of a self–assembled holiday gave customers the opportunity to break free from the AIT.

- Charter airlines traditionally had larger aircraft than scheduled airlines, with an average aircraft size of more than 200 seats, designed to pack in holidaymakers on trunk routes to the popular Mediterranean resorts. Again, that difference still exists, but is increasingly irrelevant because the charters no longer compete primarily against traditional scheduled airlines, but against a far deadlier foe — the LCCs. The impact of the LCCs on the entire European aviation industry is clear to all.

With around 60 LCCs in Europe — all but a handful of which didn’t exist before 2000 — the 21st century holidaymaker has greater choices and cheaper fares than ever before.

With minor exceptions, as charter airlines stuck rigidly to the structure of the traditional tour operator airlift in the early 2000s, the LCCs first captured a large part of the scheduled airline market and then started to pick off selected charter routes. And with substantial amounts of new aircraft arriving at the LCCs (more than 300 firm orders are due at easyJet, Ryanair and Air Berlin alone), competition with the charters will only increase, particularly as some LCCs are complementing their cheaper, more flexible links into European leisure destinations through increased links with hotel and car hire companies — i.e. other traditional components of the AIT.

The tour operator groups responded initially to the rise of the LCCs by increasing seat–only sales, and then by launching their own LCCs (MyTravelLite and Hapag–Lloyd Express for example), the success of which is considered below.

However, it’s fair to say that the impact of the LCCs has been markedly different in Europe’s two main charter markets, though this has more to do to geography that to any superior strategy from UK charters.

Essentially, the impact of LCCs is greater the closer an outbound market is to the Mediterranean, which makes LCC flights more viable economically. In Germany for example, southern European tourist destinations are close enough that LCCs can squeeze in four rotations a day on a 2/2.5 hour flight/turnaround time — a business model that is just not possible out of the UK, where usually only three cycles a day to the Mediterranean are possible.

The UK market

According to the UK CAA, charter airline passengers fell by 1.3m in 2004, to 32.1m. That represents 15% of all passengers in the UK last year — the lowest percentage for charter passengers for 20 years.

That’s due partly to the onslaught of the LCCs, but UK charter airlines argue that while their market share may be declining, in absolute terms they are either experiencing small increases in passengers flown each year or, at worst, no decline. They say that main impact of the LCCs has been to reduce growth in the charter market through siphoning off disposable incomes of some travellers, and that anyway there is little direct competition between charter airlines and the LCCs.

For example, of the 72 routes operated by Thomas Cook Airlines, the biggest "no frills" competitor is BA’s franchise partner GB Airways — whereas Ryanair competes only on one route and easyJet on nine routes.

Thomas Cook Airlines also points out that it operates "to very many points where the volume of traffic is such that a single charter aircraft operating once per week and shared between three or four tour operators works well".

It’s a fair point, and many — if not most — of the routes operated by the UK charter airlines are either too thin for the LCCs or else they are just slightly too far away to fit with the standard LCC operating model. Nevertheless, on the few "thick" UK charter routes where the LCCs do compete (to Ibiza and Palma for example) then the market share of the charters has been hit considerably.

Furthermore — and this is probably the most damaging effect of all — the UK and Irish LCCs have accelerated the trend among holidaymakers towards flexibility and demand for holidays that are not traditional 7–day and 14- day "one–size–fits–all" packages. The LCCsalso serve the hundreds of thousands of British who have bought property in France, Spain and Portugal, which can only have a negative effect on the AIT market.

And while many UK tour operators are now moving towards flexible "mix–and–match" packages, the overwhelming perception is — as one analyst puts it — that the UK tour operators are only unbundling their products "through gritted teeth" — i.e. because they finally have no choice but to do so.

At resorts where holidaymakers can book their hotel through a traditional tour operator but their flight with an LCC, how many customers will stay with the tour operators' charter airline? Brand loyalty to a tour operator or a charter airline (even assuming a customer can keep up with the bewildering changes in charter airline names) increasingly comes a poor second to price. Few charter airlines can match the fares of the LCCs — particularly if a customer self–assembles a holiday many months in advance, when LCC fares are at their rock–bottom lowest and charter fares tend to be at their highest.

So what is the strategy of the UK charter airlines as the challenge of the LCCs mounts? Manchester–based Thomas Cook Airlines operates a fleet of 21 A320s, A330s and 757s, and last year carried 2.7m passengers to more than 50 destinations.

The airline has a confusing history of name changes — it was previously called JMC Airlines, but changed to Thomas Cook Airlines as part of a decision in 2003 to re–brand all parts of the group with the Thomas Cook name. JMC itself was an amalgamation of two other charter airlines in 1998 — Caledonian Airways and Flying Colours.

Nevertheless, Thomas Cook Airlines is helped greatly by being part of the third–largest travel group in the world, the UK arm of which reported profits of £51m in the year to the end of October 2004 — it’s best financial performance for 163 years. The result was helped partly by a relaunched website that enables customers to self–assemble holidays.

In January 2005 the site was further enhanced to allow customers to assemble absolutely everything they need for DIY holidays, from currency to insurance to products from other tour operators.

While Thomas Cook Airlines admits LCC competition is hitting its own seat–only sales, its other tactic has been to switch some capacity to longer–haul charter destinations, against which the UK LCCs cannot operate economically, while trimming other capacity in order to raise yield and profitability (at the expense of market share).

As this strategy appears to be working, Thomas Cook says it has no plans to launch an LCC in the UK although, interestingly, in January this year Thomas Cook Belgium (the tour operator) launched seat–only sales on its previously "pure" charter routes (which are operated not just by Thomas Cook Airlines Belgium, but by other charter carriers) to 70 destinations. Additionally, the tour operator’s routes to Palma, Malaga, Tenerife, Alicante and Heraklion are being converted to scheduled operations, to be operated by Thomas Cook Airlines Belgium.

The Belgian tour operator sees this move as responding to passenger demand for seat–only sales (a strategy also seen at Thomas Cook Germany) and is insisting — at least for the moment — that this does not mean that the airline will change completely from a charter to a LCC operation.

But is this a strategy that will be repeated in the UK sometime in the future?

Perhaps the realistic future for UK charter airlines is shown by the relationship of Britannia Airways and Thomsonfly. London Luton–based Britannia Airways was the UK’s biggest charter airline, with a fleet of 32 757 and 767 aircraft that lifted more than 8m passengers a year to 96 destinations in the Mediterranean and the rest of the world.

Britannia dated back to 1962, but from 2000 its parent company — Thomson — became part of German–based TUI AG, the largest travel group in the world, which also owns German charter Hapag–Lloyd, LCCs Hapag–Lloyd Express and Thomsonfly, TUI Airlines Belgium, Corsair and Swedish–based Britannia.

In 2003 TUI said that it would merely "integrate low–cost elements" into Britannia Airways as an expansion of its seat–only business, and would not launch a separate LCC.

But perhaps influenced by TUI’s experience with its LCC in Germany — Hapag–Lloyd Express, which started operations in 2002 (see Aviation Strategy, January/February 2005) — a UK LCC called Thomsonfly was launched in April 2004 out of Coventry airport, with four 737–500s operated by Britannia Airways.

Initially Thomsonfly was dedicated solely to scheduled routes, but it then started flying charter services previously operated by Britannia Airways. Thomsonfly’s flight and cabin crew had different terms and conditions to Britannia staff, which helped position the LCC’s unit costs closer to easyJet and Ryanair than to Britannia Airways. Ominously, Peter Rothwell, CEO of TUI UK, said that:

"Thomsonfly is not an experiment and is not going to go away. It is a fundamental part of our business."

Although TUI Group increased earnings at its tourism operations by 75% in 2004, to €362m, while its central European operations — which includes Germany — earned €82m last year (compared with a loss in 2003), its Northern Europe sector (which includes the UK) saw earnings falls by 17%, to €65m.

The latter result was hit by a €30m charge for restructuring UK operations, which funded a cut of 800 jobs across the group in the UK in September last year as part of a refocus towards direct distribution channels.

As part of this restructuring, it was announced the Britannia Airways brand would disappear by May 2005. In justification, Peter Rothwell says that passengers do not distinguish between charter, scheduled and LCCs, but instead just want convenient flights at low prices — and will fly with any airline that provides that. Today Thomsonfly operates more than 40 aircraft to 100+ destinations from 25 UK airports, claims it will break into profit by 2006 and is apparently contemplating an order for up to 15 longhaul aircraft.

Manchester–based MyTravel Airways has a fleet of 20 Airbus and Boeing aircraft — all of them leased — and flies to short- and long–haul destinations for its parent tour operator, the MyTravel Group. Founded as Airtours International in the early 1990s by entrepreneur David Crossland, the airline was merged with fellow charter carrier Premiar in 2002 and rebranded as MyTravel Airways the same year.

Loss–making parent MyTravel Group nearly went under in 2004 after over ambitious expansion, but was rescued at the last moment after creditors and bondholders agreed to swap their £800m of debt for equity representing 96% of the company.

Nevertheless, the situation for the group is still serious, and as part of general cost cutting last year MyTravel Airways announced it was to cut more than 500 jobs (most of them pilots and cabin crew) and significantly reduce its fleet size, which then stood at 33 aircraft, by terminating or not renewing leases for 757s, 767s and a DC–10. MyTravel Airways also suffered a blow in August 2004 when COO Tim Jeans — who was previously sales and marketing director at Ryanair — resigned after just two years with the group, having transferred from MyTravelLite, where he was managing director. Birmingham–based LCC MyTravelLite was launched in 2002 with spare A320s from the group, and in October 2004 began selling seats on MyTravel Airways' services out of London Gatwick and Manchester.

Currently more than 70% of MyTravel’s UK tour operating capacity is provided by MyTravel Airways, while more than 70% of MyTravel Airways' business comes from it tour operator parent (20% come from seat–only sales, and the rest from operating for other tour operators).

With 29 Airbus and Boeing aircraft, First Choice Airways is the second largest charter airline in the UK, flying 6m passengers a year to more than 60 destinations. The Manchester–based airline is part of UK tour operator First Choice Holidays and started life as Air 2000 in 1987. In 1998 its parent bought a UK tour operator called Unijet, and merged its charter airline — Leisure International Airways — into Air 2000. In March 2004 Air 2000 was rebranded as First Choice Airways.

First Choice Airways is the only major UK charter airline to have outstanding aircraft orders — for six 787–8s, scheduled for delivery from 2009 onwards. The 270–seat aircraft will replace the airline’s existing long–haul fleet of 767–300ERs, and will be used for the revised strategy of its tour operator parent. First Choice is refocusing its tour operating business on specialist package holidays (which it is targeting to produce 50% of profits), while reducing its dependence on mainstream holidays.

The former has meant acquiring speciality tour operators such as Exodus, which packages mountain bike holidays to the Alps, while on the latter, First Choice is reducing capacity to short–haul destinations — which also means fewer seat–only sales — while increasing the number of holidays to medium- and long–haul destinations. Thus the existing and new longhaul aircraft will be used on opening up new package destinations around the world, including the US, South Africa and the Asia- Pacific region. First Choice Holidays reported operating profits of £100m in the year ending October 31st 2004 (11% up on the year before), based on turnover of £2.4bn, and wants to increase that 4.2% margin to 5% in the current financial year.

Based at London Luton and founded in the 1960s, Monarch Airlines is the largest surviving independent charter airline, operating 25 Airbus and Boeing aircraft to charter destinations globally. However, while it may retain its independence, the long–term future of the charter operation must be in some doubt, as it now operates scheduled services from London Gatwick, London Luton and Manchester to Spain, Portugal and Italy under the brand Monarch Scheduled. The scheduled operation appointed Tim Jeans — formerly of MyTravel Airways and Ryanair — as managing director in November 2004, and his brief is believed to be to turn the airline into a true LCC. 40% of all Monarch routes are now scheduled, and that number will surely rise further.

Excel Airways operates a fleet of 12 Boeing aircraft out of London Gatwick, Manchester and Glasgow to European and Middle Eastern holiday destinations. It is increasing services this summer from regional airports such as Exeter, Newcastle, Bristol and Nottingham East Midlands, and now offers total of 40 destinations from 10 UK airports.

The airline launched in 1994 under the name Sabre, but became Excel Airways in 2001.

During its short history the London Gatwick–based airline has had a number of owners, but in January 2005 it was bought by the Avion Group, an Icelandic aviation holding company that also owns Air Atlantia Icelandic and Islandsflug — wet–lease specialists that are merging their operations — and Air Atlanta Europe, another wet–lease specialist, based in the UK. In November 2004 Excel Airways Group launched Aspire Holidays, a specialist tour operator for tailor–made luxury holidays.

Air Atlanta Europe operates a fleet of five 767s and two 747–200s, and the Avion Group says it will "seek synergies" between Air Atlanta Europe and Excel Airways where possible, and although this is not believed to include a merger at this stage, sources indicate this is the long–term plan. Air Atlanta has provided aircraft to Excel Airways for many years (in summer 2004 Excel leased four of its aircraft), and in 2004 the two companies signed a five–year aircraft supply deal.

The German market

The German tour operator industry is dominated by the two giants — TUI (previously known as Preussag) and Thomas Cook AG (previously known as C&N Touristic). However, despite the size of these two groups, they have been severely affected in the last few years by the effects of recession in the German economy, higher fuel prices and by the rise of the LCCs, a concept that started taking off in Germany as late as 2002.

LCCs provide fierce competition to the charters and contribute to overcapacity on many routes out of Germany — not a good situation to be in when demand is weak historically. The TUI Group initially reacted to the rise of the LCCs in Germany by refocussing its charter airline — Hapag–Lloyd — as both a charter and low cost carrier, with seat only sales at Hapag–Lloyd marketed as a "no–frills" product that can be used for flexible packages. As part of this effort an internet site for seat–only sales (which account for more than 20% of all Hapag–Lloyd’s revenue) was launched in 2004.

In January 2005 TUI brought Hapag–Lloyd and LCC Hapag Lloyd Express into one division, reporting to airline CEO Wolfgang John, in order to benefit from savings in marketing, IT and other areas, although TUI claimed they would remain operationally independent.

In April, however, TUI rebranded Hapag–Lloyd as Hapagfly in order to help boost seat–only sales further in the face of increasing LCC competition. In January the former Hapag- Lloyd ordered 10 737–800s, which will be delivered between January 2006 and the summer of 2007. The deal is estimated to be worth $655m, and the aircraft will replace six A310s, which are up to 16 years old, and make TUI’s entire fleet (across five airlines) almost entirely an all–Boeing operation. The Hapagfly fleet will then stand at 45 737–800s.

In November 2005 Hapagfly will also become the first charter airline in Germany to lower its commission to travel agents.

TUI’s move copies the strategy of Air Berlin, which was previously a charter specialist operating for German tour operators.

However, as the industry coalesced around two giant tour operating groups, Air Berlin was forced to change business model in 2002.

Now reinvented as LCC (see Aviation Strategy, December 2004), it operates 49 aircraft and provides capacity for tour operators such as TUI and Thomas Cook AG to destinations mostly around the Mediterranean. From November 2004 Air Berlin also deepened its existing code–sharing with TUI’s Hapag–Lloyd, which led to speculation that one day TUI would acquire a stake in Air Berlin.

In 2004 just 40% of Air Berlin’s total revenue of €1.05bn came from tour operators, with the rest coming from seat–only sales (the privately–owned airline does not reveal profit levels). The percentage coming from tour operators is set to fall further as almost all of the 19% rise in turnover in 2004 came from Air Berlin’s low–fare City Shuttle services, and the same pattern is expected this year, when revenue is forecast to rise by another 20%, based on a 14% rise in total passengers carried (to 13.7m). And it’s likely that few of Air Berlin’s massive order for 70 A320s, placed in November 2004 and arriving from this November onwards, will be dedicated to charter operations.

Condor is the German charter operator for Thomas Cook AG — the former German travel giant C&N Touristic, which adopted the Thomas Cook AG name after acquiring the UK tour operator in 2001.

In March Thomas Cook AG revealed operating profit of €22m for the 12 months to the end of October 2004, compared with a €79m operating loss the year before, and a net loss of €149m in 2004, compared with a €280m net loss in 2003. But while sales in the UK rose by 5% in 2004, revenue growth in Germany — which is the most important market for Thomas Cook — was just 1%.

Indeed the German market has been very tough for Thomas Cook AG over the last three years, and in 2004 it cut 10% of its German workforce and carried out a wide–ranging review of its airline operations, aimed at reducing costs by €100m. Hundreds of jobs are going at the two airlines — Condor and Condor Berlin (a Berlin–based charter carrier, with 12 A320s) — and the Condor fleet was reduced by 12 aircraft, to the current fleet of 23 Boeing aircraft.

Substantial savings were also made at its charter airlines after Verdi, the general services union representing ground staff;

Unabhängige Flugbegleiter Organisation (UFO), the cabin crew union; and Vereingung Cockpit, the pilots' union, agreed to pay freezes and substantial increases in productivity.

Thomas Cook AG’s charter airline has — like many of its rivals — suffered from constant tinkering to the brand. Condor changed its name to the curiously–titled "Thomas Cook Airlines powered by Condor" in 2002, but this decision was reversed just two years' later, and in May 2004 the airline became known as Condor again — at a cost of €4m.

The brand was brought back specifically to spearhead a fight back against the encroachment of the LCCs, through increasing the amount of seat–only sales. A lower fares structure, based on the flexibility of the ticket, was adopted for seat–only fares with the intention of increasing the proportion of seat–only sales from 20% to 40%. Ralf Teckentrup, the Thomas Cook AG board member responsible for airlines, admitted that: "The tour operator market we have focused on up until now has been in decline over the past two years. Condor must therefore work hard to achieve a significant improved market share in the seat–only sales segment."

Condor’s future may be affected by changes at its parents. Condor is owned 90% by Thomas Cook AG and 10% by Lufthansa, while Thomas Cook AG is in turn owned 50% by Lufthansa and 50% by KarstadtQuelle, a German retail stores and mail–order company. However, in April — after announcing a €1.6bn loss for 2004 — KarstadtQuelle announced it was likely to sell its stake in Thomas Cook.

And in May reports started coming out of Germany that Lufthansa is also about to review its stake–holding in Thomas Cook AG, with speculation that it may want to exit the tour operating industry altogether.

LTU International Airways was originally a pure charter player, and today still operates charters both to the Mediterranean and to long–haul destinations for a variety of German tour operators. However, LTU struggled in the early 2000s, and new management turned the airline around through a restructuring programme that included the adoption of an all- Airbus fleet and an extension into scheduled services and the business traveller market. Today a large majority of LTU’s flights are operated as scheduled services, using a fleet of 23 A320s and A330s. The airline is owned 49.9% by a private German trust called VBE Beteiligungsgesellschaft (which bought Swissair’s stake in 2001) and 40% by German tour operator Rewe Touristik.

Germania is a wet–lease specialist that operates charter flights for several German tour operators with a fleet of 22 737s and MD 82/83s. It also owns LCC subsidiary Germania Express, which was formed in 2003, but this brand disappeared after 12 of its 16–strong fleet of Fokker 100s and 15 routes were absorbed into LCC DBA in March this year, after a tie–up between the two airlines that saw Germania owner Hinrich Bischoff acquire 64% of DBA. The enlarged DBA is now the third–largest airline in Germany (behind Lufthansa and Air Berlin). Germania says its charter operations will not be affected by the merger of Germania Express into DBA.

Aero Flight was founded in 2004 from the assets of Aero Lloyd, which ceased trading in 2003. It operates out of Frankfurt and Dusseldorf to destinations across Europe with a fleet of four A320s and two A321s.

A charter future?

Charter airlines reacted initially to increasing competition from the LCCs by increasing the proportion of seat–only sales, but the impact of this has only been marginal to customers keen to self–assemble their holidays (as charter airlines' seat–only products — even if they can be found — are usually no match for LCC product found during searches on specialised internet search engines). Increasingly, the most far–sighted of the charter airlines realise that seat–only sales are not the only answer to the LCCs.

Other strategies that UK and German charter airlines/tour operators are adopting include:

- Become fully flexible. "Dynamic packages" is the latest buzz phrase among tour operators -i.e. allowing holidaymakers to mix and match different elements of their holiday, rather than accept the one–size–fits–all. Tour operators used to think (and some still do) that they cater for this market through seat–only sales:

TUI, for example, has more than 50 internet portals that generate close to €1bn of revenue each year, yet still TUI continues to insist that only a small minority of package holidays will ever be booked online. But adding an internet sales channel for seat–only sales is no longer good enough; tour operators must add other products — such as flights and hotels — from rival companies if they want to offer a truly flexible service to holidaymakers. - Turn into LCCs. Although merging the culture of the LCCs with the strengths of the charters is difficult, charter airlines that can cut costs to the level of the LCCs will have a massive advantage. But being an LCC is more than just about low costs. Charter airlines are all about maximising load factor in order to maximise customers to the tour operator’s hotels.

This means fares are lowered as departure times get closer, whereas LCCs do the exact opposite — they increase fares, which may not maximise load factor, but does tend to maximise margins. Are charter airlines brave enough to adopt the LCC pricing model?

- Manage a dignified retreat in Europe destinations where the LCCs are encroaching, and instead stick to high–density routes where the volume of pure package travellers looks set to stay higher than seat–only sales. They may be niche markets, but could be defendable in the medium–term.

- Build up a network of long–haul destinations (such as North Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean and Asia) that simply do not fit in with the business model of the LCCs. Charters can use the traditionally larger — and longer–range — charter aircraft to provide airlift for markets that the LCCs cannot compete with (for fear of fleet complexity and increasing costs per ASK). This means destinations more than two hours' flying time away — the limit over which LCCs lose a vital round trip per day.

This strategy also taps into the growing demand for non–traditional holiday destinations.

The bet here is that LCCs will not chase the charter airlines into these markets, because to do so means buying new aircraft types.

Some or all of the above strategies may be effective barriers to the encroachment of the LCCs in the short–term, but how many of them will still be useful five years from now? That’s difficult to say, but it’s probable that charter airlines will need to keep reinventing themselves and find new strategies if they want to survive.

However, the one core weakness that charter airlines have is that they are largely at the beck and call of their owners, the tour operator groups, and are not free to react quickly to market changes and to serve whomever they want with whatever business model they want.

Until the structural changes of the last few years, the protection of financially secure owners and a guaranteed demand for their product was a huge advantage, but this situation has now changed. With LCCs rampaging in the market, managements at some of the charter airlines realise that in order to beat off this challenge they may have to break way — as much as they can — from the business model hoisted onto them by tour operator owners.

They can no longer be bound to a tour operator view of a market that is six to nine months away — i.e. with hotels and seat capacity contracted well in advance of the next summer season (often on long–term contracts), while hoping to sell as much of their capacity to holidaymakers in advance as possible.

Add to this the obsolescent IT and internet booking systems of the tour operators, multiple aircraft types and constant brand and livery changes, the case for cutting the links with tour operator parents looks obvious — one London analyst believes the charter airlines can survive only if "they are freed from the conservative management at the tour operators", which are essentially "low margin businesses with too much capacity".

The problem with this, of course, is that the tour operators would no longer be guaranteed airlift for the summer season, and would have to bid against competitors for capacity from their former in–house airlines. Then again, the tour operators would be free to contract the cheapest airlift from all charter airlines — or even the LCCs. Are tour operator parents brave enough to make this decision? The future of the charter industry in Europe may well depend on it.

| Thomas | MyTravel | Britannia | Excel | Choice | Monarch | |

| Cook AL | Airways | Airways* | Airways | Airways | Airlines | |

| A300-600R | 4 | |||||

| A310 | ||||||

| A320-200 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 5 | ||

| A321-200 | 4 | 4 | 7 | |||

| A330 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 737-300 | ||||||

| 737-400 | 2 | |||||

| 737-500 | 4 | |||||

| 737-700 | ||||||

| 737-800 | 6 | |||||

| 757-200 | 12 | 3 | 19 | 17 | 7 | |

| 757-300 | 2 | |||||

| 767-200ER | 4 | 2 | ||||

| 767-300ER | 2 | 9 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 787-8 | (6) | |||||

| MD 82/83 | ||||||

| Total | 21 | 20 | 36 | 12 | 29 (6) | 25 |

| Condor | Aero | |||||

| A300-600R | Condor | Berlin | Hapagfly** | LTU | Flight | Germania |

| A310 | 6 | |||||

| A320-200 | 12 | 9 | 4 | |||

| A321-200 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| A330 | 10 (2) | |||||

| 737-300 | 5 | |||||

| 737-400 | ||||||

| 737-500 | ||||||

| 737-700 | 10 | |||||

| 737-800 | 29 (10) | |||||

| 757-200 | 1 | |||||

| 757-300 | 13 | |||||

| 767-200ER | ||||||

| 767-300ER | 9 | |||||

| 787-8 | ||||||

| MD 82/83 | 7 | |||||

| Total | 23 | 12 | 35 (10) | 23 (2) | 6 | 22 |