British Airways' CeBA vision

June 2004

British Airways, as part of its strategic priorities (on which we reported in the April issue of Aviation Strategy) has incorporated a vision of a "Customer–enabled BA" or CeBA for short, as part of its strategy. The company’s vision statement is "Dealing with BA will be so easy that our customers can choose to serve themselves".

The prime motivation behind this must be to remove human interaction as much as possible in anything but face–to–face front end operations. This is a trend that we as consumers see in all aspects of dealing with large companies. The best example may be in the proliferation of voice and tone activated automated call services where the customer increasingly pays for the inefficiencies or limitations of operations.

BA sees CeBA as a bit more than this cynical view. It is a fundamental part of simplifying the business processes that is the core of its strategic aspirations. It describes it as a multi–functional programme that aims to cover the full process of the customer’s experience from booking to returning home.

As an essential element it tries to streamline the product offering in order to ensure consistency of delivery and elimination of duplication. In addition it helps that the internet is proving a viable way for the consumer to interact with internal systems without the intervention of any human agent. The company estimates that the implementation is worth some £100m in annualised benefits.

While reducing costs and cutting personal service, BA wanted to make sure that the customer remains "happy" — in its management–speak, "making the interaction with BA an easier and richer experience".

To that end it wanted to make sure that after implementation the customer would be comfortable in agreeing that: its products and services are simple to understand; there is an assurance that transactions are successful; the product offering is crystal–clear; in case of service disruption there is adequate communication and assistance for rearrangement of travel plans; there is consistency in communication ("I get the same answer whomever I ask").

Above all, the customer has to do it all himself on ba.com and increasingly he or she will get charged for talking to a human.

For any of the legacy carriers from the restrictive IATA period this would be an uphill struggle. As a result of the way the industry developed, BA itself had millions of fare types, 72 selling classes, 7 different cabins, classified 15 different types of customer, 10 different ways to pay, 9 kinds of check–in ... and the rest. It estimated that it employed some 12,000 people merely to translate its internal systems to allow the execution of everyday transactions for customers.

Because of the number of information systems the customer rarely got the same answer to the same question. The complexity and number of systems and processes made change and improvement incredibly slow.

In the first year of implementation however, the company has achieved some major improvements. Half of all UK short–haul leisure fares are now booked online at ba.com. All of the frequent flier transactions are available online. The company has halved the number of fares (alright there are still more than a million of them!). It has simplified and unified all the fare rules and conditions from some 3000 to 3 basic types. Selling classes now have tightly defined yield bands and common conditions. The use of eTicketing has doubled to 50% of all bookings.

Furthermore, over 50% of its low fare offerings — the most expensive to administer — are booked online.

As part of the selling message the customer is forcefully told that to get a paper ticket or to talk to an agent will cost more than just doing it all online. The followers of Diogenes may rightly say that you may well still get different answers to the same question — but now you have to pay for them.

The ba.com site meanwhile has been further enhanced. It can now handle large groups, take payment by debit card (which is a major saving), allows booking of tickets for other people, and the paying for tickets from other countries. It dynamically provides for upgrading and advanced product selling.

For the customer it provides full management of the travel process apart from the flight itself: change and update bookings, allocate seats, choose meals and check–in. Also the company is starting to roll out the ability for home–printed boarding passes.

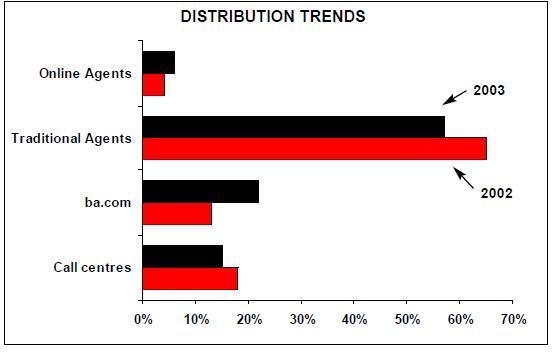

BA is seeing a structural shift in distribution patterns. In the UK still by far the majority of bookings go through travel agencies. However this is falling — last year by around 8 percentage points to below 60% of total bookings and call centre bookings have fallen by 3 percentage points to around 15%.

Web bookings have taken up the slack with a nine point jump on ba.com to around 21% of total bookings with the rest provided by other online engines.

In designing its web offering BA has taken leaves out of many books — not least its LCC competitors — but more importantly has not just transferred its internal booking engine to hook on to the back of some ill–designed web pages. It has gone back to basics: how on earth do we get someone to book with us? In today’s world the answer may well be to make it cheap and easy and then tell them they want it and that it is good for them.