Debt mountain looms on horizon

June 2003

Even though many of the large US network carriers have implemented impressive cost cuts and may return to marginal profitability in 2004, their problems will be far from over because of the damage that years of weak cash flow and heavy borrowing have inflicted on their balance sheets.

A special report from Fitch*, the credit rating agency, in late May argued that significantly higher cash obligations related to debt, aircraft leases and pension funding would put heavy pressure on airline liquidity through at least 2006.

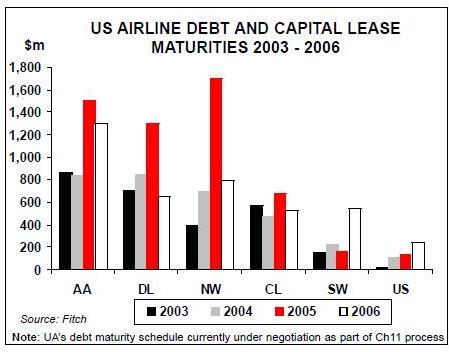

According to Fitch, the ten largest US carriers face $21.2bn of debt and capital lease maturities between 2003 and 2006.

In addition, the airlines had a similar $22bn aggregate underfunded pension liability at the end of 2002. As the Fitch analysts put it, this represents an "immense cash funding requirement at a time when operating cash flow may well remain weak".

It is hard to put such figures into context, but it is worth noting that industry revenues have fallen from $96bn in 2000 to an estimated $78bn in 2003 and that, when the recovery occurs, it is expected to be slow.

The US major carriers are currently projected to lose another $6–7bn in 2003 and, at best, become only marginally profitable in 2004.

Some of the debt coming due in the next few years will undoubtedly be refinanced.

However, the Fitch analysts are not pinning much hope on the industry’s ability to borrow in the future because of "diminished unencumbered asset bases and limited investor appetite for new airline exposure".

Needless to say, low–cost carriers like Southwest, JetBlue, AirTran and Frontier will not be facing similar liquidity pressures because of their competitive cost structures, modest debt loads and lack of expensive "defined–benefit" pension plans.

Burdensome debt maturities

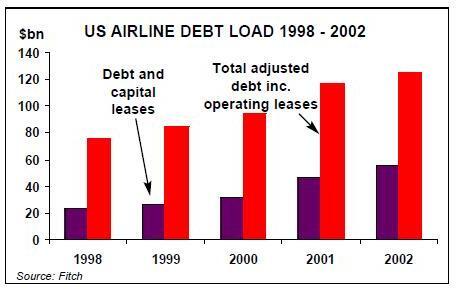

US airlines' debt load has more than doubled over the past four years. According to Fitch, industry debt and capital lease obligations surged from $23.3bn at the end of 1998 to $55.8bn at year–end 2002. Lease–adjusted debt (including operating leases, capitalised at eight times gross annual rental expenses) rose from $75.9bn to $125.6bn in the same period.

The post–2001 borrowing has enabled US airlines to survive through the prolonged industry crisis. However, the industry’s lease adjusted debt–to–total–capital ratio has risen to 95% — the highest leverage ratio ever witnessed (in the pre–September 11 days the ratio was around 70%).

The problem has been compounded by the fact that most of the recent borrowing has been short–term — typically for 4–5 years — because it has been taken to shore up liquidity.

By contrast, before 2001 most of the new debt and leases were taken to fund new aircraft deliveries, which typically meant long term mortgage–type financings or leveraged leases that involved the issuance of EETCs.

Therefore, in addition to the higher interest, lease costs and maturities, much of the new debt will begin to mature in a couple of years' time, putting added stress on cash flow in a critical recovery period.

The report suggested that 2005 and 2006, when some large bank credit facilities mature, could be difficult years even for otherwise strongly positioned carriers like Northwest and Delta. Northwest’s debt and capital lease obligations peak at $1.7bn in 2005, and its secured bank credit facility (currently $962m outstanding) also matures in October that year. Delta, which recently refinanced the bulk of its near–term debt repayments, still has $1.3bn of debt coming due in 2005.

The Fitch report made the point that, in order to avoid a cash squeeze in 2005, Northwest and Delta would depend on continued access to the capital markets and the willingness of secured lenders to roll over existing debt. However, given those airlines' excellent record so far, it is hard to envisage them not being able to refinance the debt.

Having recently averted bankruptcy thanks to labour concessions, AMR still faces liquidity issues.

It has significant fixed cash obligations, including $839m in 2004, $1.5bn in 2005 and $1.3bn in 2006. Also, its fully used $834m secured bank credit facility matures in December 2005 — or, in the worst case scenario, this summer — if AMR is not able to meet the covenant requiring at least $1bn of unrestricted cash. It had only $1.27bn of unrestricted cash at the end of March.

Continental’s current liquidity position is also weak, but Fitch believes that its relatively light debt maturity burden beyond 2003 ($470m in 2004, $680m in 2005 and $527m in 2006) will allow it to make more progress in repairing its balance sheet. It is also worth noting that Continental has consistently outperformed its competitors on both the revenue and cost fronts and is expected to be among the first network carriers to return to profitability.

US Airways' post–bankruptcy balance sheet has been significantly de–leveraged. It now has "more manageable" debt and capital lease maturities of $109m in 2004, $141m in 2005 and $245m in 2006.

Before its Chapter 11 filing United faced debt and capital lease repayments of about $1.2bn in 2004 and more than $600m in both 2005 and 2006. It is too early to speculate what the balance sheet might look like if and when the airline emerges from Chapter 11.

Fitch merely noted that the repayment obligations would be restructured to ease the 2004- 2006 financing cash flow burden but that those reductions would be partly offset by any government–guaranteed loan.

Refinancing prospects

After relying heavily on secured borrowing over the past few years, the major airlines have seen their unencumbered asset bases dwindle dramatically. Many have recently pledged the last of their remaining desirable assets — either to secured creditors in private transactions (Continental), DIP lenders (United) or lenders supported by a federal guarantee (US Airways).

Northwest, in turn, is finding that its unencumbered DC–9s and DC- 10s no longer represent attractive collateral for investors that have become increasingly selective.

Only Delta and American retain unencumbered asset pools large enough to support significant additional borrowing. However, even those airlines have relatively little left in terms of Section 1110–eligible aircraft, which enjoy special status in Chapter 11 proceedings and are therefore most attractive to investors. At the end of March, Delta and American had only $500m and $700m in Section 1110–eligible unencumbered aircraft,out of total pools of $2.9bn and $2.8bn, respectively.

Furthermore, the Fitch report suggested that neither of those carriers would be able to borrow up to the full estimated values of their Section 1110–eligible assets.

In Delta’s case, this is because the pool consists of MD–11s and MD–90s that have limited market appeal.

AMR, in turn, "may look for ways to avoid pledging these assets in an effort to preserve collateral for a future DIP facility in Chapter 11".

All of this led Fitch to conclude that "future access to the capital markets is likely to be very limited for all but the best–positioned carriers".

The agency also noted that, despite Northwest’s success in raising $150m through a convertible note offering in May, "prospects for extensive issuance of unsecured debt by the network carriers remain poor".

In that respect the report may be painting an unnecessarily gloomy picture. The US major carriers and their bankers are known for their ingenuity in coming up with new ways of raising funds. Also, at least the stronger carriers like Delta and Northwest should be able to refinance their 2005 debt obligations — as long as they secure pilot concessions to reduce costs to the new levels set by American and United.

Also, four US airlines (Northwest, Alaska, AirTran and Delta) have completed convertible debt offerings in recent months, and Continental announced one in early June. The latest completed deal was Delta’s private placement of $300m of 20–year convertible bonds at the end of May. The method, which was popular among airlines in the early 1990s, was revived by Continental in January 2002. The unsecured notes, which can be converted into shares, are a good cash–raising tactic for airlines that lack unencumbered assets. By selling the equity option, the companies can secure low–cost financing. The deals are less risky for investors than share offerings.

While bond analysts caution about reading too much into the latest convertible deals, they nevertheless mark the return of the large network carriers to unsecured financings after many years and show that the capital markets are not totally shunning airlines.

The deals obviously reflect improved investor sentiment (end of war, reduced bankruptcy concerns, stronger summer season, rising stock prices, etc.), despite the lack of any concrete sign of recovery in industry fundamentals. In a recent research note, Merrill Lynch analyst Mike Linenberg called it a "positive trend for the industry, as until recently airlines were unable to tap the capital markets".

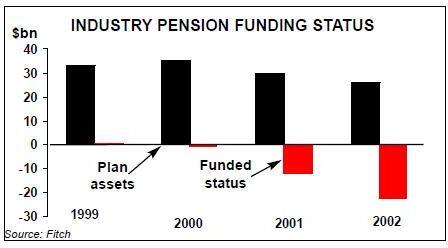

Pension funding requirements

After three years of poor pension plan asset returns, declining interest rates and accruing benefit obligations tied to costlier labour contracts, the US major airlines have witnessed a sharp decline in the funded status of their defined–pension plans. According to Fitch, the eight carriers with defined–benefit plans moved from an aggregate over–funded position of $700m at the end of 1999 to an underfunded obligation of $22.5bn at the end of 2002. Of the $22.5bn total liability, United accounted for $6.4bn, Delta $4.9bn, Northwest $3.9bn, American $3.4bn, US Airways $2.4bn and Continental $1.2bn.

On the positive side, this year’s revisions to labour agreements (so far, at US Airways, United and American) will help limit the growth of future pension obligations.

However, the report argued that, absent the termination of a defined–benefit plan in Chapter 11 (as at US Airways) or its replacement with cash–balance plans (at Delta for non–pilot groups), it would be hard for airlines to avoid meeting their pension plan obligations.

Under defined–benefit plans, annual cash funding requirements are mandated by federal law.

In Fitch’s estimates, in the absence of improved pension plan asset returns or an increase in the applicable discount rates, nearly all of the US majors will face substantially higher cash funding obligations in 2004- 2006. Over the next two years, American and Delta would be required to pay $750m-$1bn, United $1.5–1.8bn, Northwest $900m-$1.2bn and Continental $350–600m.

US Airways averted the problem by using the Chapter 11 process to terminate its pilots' pension plan and replace it with a version that reduced and spread out funding requirements.

The Fitch analysts suggested that United would probably have to follow suit, because its existing pension obligations would be "unmanageable" and impede its ability to attract outside equity investors.

In the meantime, Northwest is asking the Department of Labor for an exemption that would allow it to fund its pension requirements for 2003 and 2004 rather creatively — with the stock of its wholly owned regional subsidiary Pinnacle. If allowed, the company would save $330m in cash.

Aircraft capital commitments

US major airlines have generally done a very good job in deferring new aircraft deliveries since September 11. In fact, now most of the aircraft capital commitments over the next three years are for regional jets.

However, the Fitch report ticked off American and Continental for taking large jet aircraft at a time when significant numbers of aircraft remain parked. American is taking 11 Boeing widebody aircraft in 2003 (because it was unable to defer them), while Continental will resume Boeing aircraft deliveries in October (as part of its fleet renewal plan).

Needless to say, Boeing Capital is providing backstop financing for all of those aircraft.

Northwest continues to take delivery of large numbers of mainline aircraft and RJs as part of its ongoing fleet renewal programme, which involves spending $1.75bn this year and $1.2bn in 2004. However, virtually all of those aircraft were pre–financed with earlier EETCs.

Further government assistance?

Since September 11, the government has provided a total of $7.3bn in cash payments to US airlines — $5bn in late 2001 and $2.3bn in security fee reimbursements in May 2003.

The ATSB has approved $1.6bn in federally guaranteed loans, and the government has assumed an equity position (through warrants) in America West, US Airways and ATA. In addition, the airlines have collected billions of dollars in tax refunds through revised "net operating loss (NOL)" provisions, which enabled them to use their 2001 and 2002 losses to recover federal income taxes paid in 1996- 2000.

The problem is that there may not be any more assistance on the horizon. The federal tax credits tied to operating losses have by now been largely exhausted. The Fitch analysts also rate the probability of another round of cash payments as "quite low" — a conclusion that most Washington observers would probably agree with.

Nevertheless, as the report points out, the government remains a wild card in shaping the future of the industry. United’s application for loan guarantees as part of its Chapter 11 exit financing package could provide an interesting test, particularly if the airline has not secured equity or other financial support from the private sector.

The Fitch analysts see hope in legislative moves to ease some of the financial burden associated with the funding of defined–benefit pension plans. Much of it is in the context of general pension reform for all US companies, though there are some proposals specifically related to airlines.

Among other things, proposals under discussion would allow US companies to delay making deficit reduction contributions for five years and to amortise underfunded liabilities in equal instalments over 20 years. The report suggests that the government’s efforts with pension reform "could be decisive in removing one of the key financial challenges facing the major network carriers over the next several years".