United: in gradual recovery mode

June 2002

In recent months the stock market has treated United Airlines as if it was a failing carrier rather than one in a gradual recovery mode. After all, UAL’s unprecedented 2001 financial losses, dismal employee relations, high labour costs and continued leadership uncertainty have made it look like a potential Chapter 11 candidate.

While most other US major airline stocks have recaptured typically 20–30% of their pre–September 11 value, UAL’s shares have languished at the post–attack lows. The shares recently dipped close to the record low of $9.40 recorded in November and have since settled in the $10–12 range — a level that represents less than one third of their pre–September 11 value.

However, at least two Wall Street analysts — Glenn Engel of Goldman Sachs and Jamie Baker of JP Morgan Securities — recently decided that the stock had been punished enough and that UAL’s recovery prospects might in fact be quite reasonable.

Both analysts upgraded UAL to a "buy" and issued surprisingly upbeat reports on the company. Engel — the first to move in mid- May — set a nine–month share price target of $20, while Baker initiated UAL coverage for JP Morgan with a two–year price target of $24.

The analysts cited UAL’s strong liquidity position, substantial unencumbered assets, attractive route network, gradually recovering market share, vastly improved operating performance and recent success in clinching the final open labour contract.

Interestingly, the analysts also took the view that United’s losses or recovery prospects were not materially worse than American’s. Baker pointed out that, in absolute terms, United’s net losses were actually lower than American’s in the past two quarters, yet since September 11 UAL’s shares have seen a 62% correction, compared to AMR’s 31%. According to his prediction, the largest major airline was likely to lose only $130m less than United in 2003.

While this may simply imply that American is now also on the endangered carriers list (as the industry recovery trends have slowed), what the analysts are saying is that United’s recovery prospects no longer seem more uncertain than those of the rest of the industry. Based on the share prices, Engel subsequently recommended that investors switch their holdings from AMR to UAL.

Equally controversially, Baker argued that United needs labour concessions to thrive but not necessarily to survive. He envisages a net profit of $2–3 per share in 2004 even without any help from labour. Of course, UAL’s chairman and CEO Jack Creighton told shareholders at the company’s annual general meeting that UAL was in a "fight for its future" and had a "long way to go in our climb back to financial stability".

As Aviation Strategy went to press, the airline was still trying to ascertain what, if any, financial concessions its employees and business partners might be willing to make, so that it could decide whether or not to apply for federal loan guarantees (the deadline for submitting applications is June 28).

Why the investor concerns?

One thing that differentiates United from most of its competitors is that its financial problems began long before September 11.

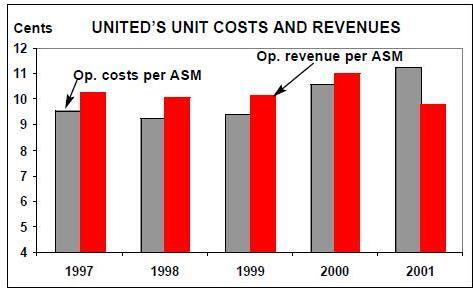

The troubles started with the ending of the ESOP in 2000, when wages snapped back to the pre–1994 levels and all of the labour contracts became amendable (employees originally secured 55% of UAL’s stock in exchange for a 15% wage cut). United subsequently became the first major airline to grant hefty pay increases to its pilots which, in combination with the wage snap–backs, led to a sharp hike in labour costs.

As a result of unprecedented cost pressures, UAL posted a $124m loss for the fourth quarter of 2000 and another $604m loss for the first half of last year. Even before the terrorist attacks, the company was headed for a $1bn net loss in 2001.

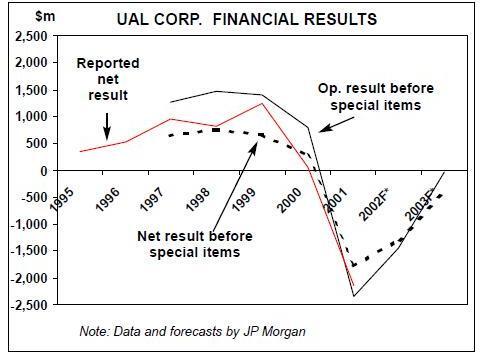

As things turned out, UAL reported a net loss of $2.1bn (or $1.8bn before special items) for 2001 — the largest annual loss ever recorded by any airline — and a $510m net loss for the first quarter of 2002. The latest pretax loss margin of 23% before special items was the industry’s second worst (after US Airways).

While United has implemented impressive cost cuts since September 11, its revenue decline has been the industry’s sharpest primarily because of its high business traffic content.

United was also plagued by labour strife over the winter, because all of its IAM–represented workers were still without new contracts and at 1994 wage levels. The airline averted a mechanics' strike at year–end only because of the intervention of a Presidential Emergency Board. A rescheduled strike was averted in early March when the mechanics ratified a new five–year contract that will make them the highest paid in the industry.

Another strike threat was averted in late April when a tentative four–year contract was reached with IAM–represented public contact, ramp service and related employees.

Its ratification in mid–May was an important milestone, because it was United’s last remaining open contract. Completing that process enabled the airline to finally focus properly on concessions talks with all of its unions.

However, that piece of good news went unnoticed by the market. Instead, attention was diverted to an unusually stormy AGM, during which UAL’s leadership was subjected to a barrage of criticism from angry shareholders and employees. The shareholders passed three proposals against the board’s recommendation, namely linking executive pay to the company’s recovery, separating the positions of chairman and CEO, and requiring shareholder approval for any airline acquisitions. These were dubbed as "wake–up call" resolutions, but the debacle only really served to reinforce the perception of a dysfunctional organisation.

Among other things, United’s employees are still angry about two costly projects that the previous leadership embarked on in 2001 — the proposed $4.3bn acquisition of US Airways and the launch of Avolar business jet subsidiary. The merger proposal stumbled on antitrust issues and was terminated in July 2001, while Avolar’s closure was announced in March 2002. The business jet venture seemed to be a bright idea, but it was not able to attract outside investors — and it was just too much of a distraction for UAL.

Also, there continues to be uncertainty about the CEO’s office. The previous CEO, James Goodwin, was forced to resign in October 2001 after losing the confidence of employees. The current CEO Jack Creighton, who stepped in on an interim basis after being a board member since 1998, recently announced his intention to step down as soon as a successor is found.

Creighton is generally considered to have done a reasonable job under difficult circumstances, but he is 69 and wants to retire.

While Creighton is determined to ensure a smooth transition and is known to be keen to complete the concessions talks before his retirement, there is real concern about United’s ability to attract strong outside candidates. Given the unusual governance structure and the challenges involved, there may not be much interest in what is regarded as the toughest US airline CEO’s job.

One of the top candidates, former Continental president Greg Brenneman, has to be out of the running now that he has accepted the position of CEO of PricewaterhouseCoopers Consulting (or Monday, as it has bizarrely rebranded itself).

Investor confidence has not been helped by the fact that United has released little detail of its financial recovery plan. The airline has been understandably hesitant to disclose the amount of concessions sought, for fear of jeopardising dealings with the unions, and it first needed to complete all the contract talks — a process that Creighton has conceded took much longer than he had anticipated. However, in comparison, US Airways did release its overall cost savings and revenue enhancement targets, which helped reassure investors that there was a plan.

Strong liquidity

Unlike US Airways, however, United has little risk of running into a liquidity crisis in the foreseeable future, and its financial flexibility remains good. The company had a healthy $2.9bn cash balance at the end of March and, significantly, $3.5bn of unencumbered aircraft and engines.

Despite its heavy financial losses, United has succeeded in raising some $2.5bn through secured long–term financings over the past 12 months. First, it raised $1.5bn in a EETC transaction in August 2001 — luckily three weeks before September 11.

This and another $300m long–term debt financing last summer meant that the airline entered the industry crisis with strong liquidity.

The public EETC offering was several times oversubscribed and incorporated a record–low effective interest rate of 6.59%.

At that time investors already knew that United was headed for a $1bn loss in 2001, but it evidently did not matter because the Section 1110 repossession provisions and liquidity facilities in EETCs provide what are generally regarded as adequate protections to investors.

Second, United closed a $775m long term debt financing, albeit in the private market, in late January — the same week that it reported the 2001 losses. That transaction refinanced a large obligation on existing aircraft that had come due and raised $250m in cash. Of course, United has also collected about $650m in government cash grants and $600m in federal income tax refunds since September 11.

The airline’s contractual cash obligations add up to a substantial $4.4bn in 2002, though that includes just $1.2bn of long–term debt maturities. The most significant obligations for the remainder of the year are $300m of bank revolver debt coming due in the autumn and a final $500m payment on 1997 EETCs in December. This year’s capital spending was earlier slashed by 50% to $1.2bn, but the cash requirements are just $400m because all of the 24 new aircraft taken in 2002 have financing in place.

The rest of this year’s cash obligations consist of operating lease payments ($1.6bn) and capital lease obligations ($413m). As a result of order deferrals, there will be no new aircraft deliveries in 2003.

On the basis of its market share, United could apply for up to about $2bn of federal loan guarantees, though something closer to $1bn might be more appropriate. The airline’s top executives have suggested that the June 28 deadline could be helpful in putting pressure on the unions and business partners to grant concessions but, realistically, it may not make any difference.

The loan guarantee guidelines require applicants to be carriers for whom "credit is not otherwise reasonably available". Even if United gets its unions and partners to cooperate, it is hard to see how it could convince the ATSB of need because of its strong cash position and likely ability to borrow through normal commercial channels.

The airline is expected to refinance the bulk of the debt obligations due in the remainder of this year. While it has continued to deny that any specific transactions are in the works, JP Morgan’s Baker suggested in late May that it was close to refinancing nearly $900m of obligations. The real issue for United may be a growing debt burden, rather than ability to borrow.

Quest for labour concessions

United’s unit labour costs have been running 5–10% higher than the industry average since 2000, when the new pilot contract was signed, and this year’s two new IAM contracts have added to the pressures.

Baker calculated that this puts United at a $450- 600m deficit to the industry average labour CASM. Clearly, to return to better than marginal profitability from 2004 onwards, the airline needs to reduce labour costs.

United is believed to be seeking several billion dollars of labour concessions, spread over several years. Formal meetings with union leaders began in late April. As a major breakthrough, the pilots agreed to talks on the subject. The IAM–represented workers will also be attending the meetings, because their new contracts require them to do so.

However, the flight attendants have refused to participate in any talks about wage concessions. They are in a unique situation in that, unlike the other key unions at United that have industry–leading wages, their pay is pegged to the average of four other top airlines.

Also, the pilots have made clear that they are willing to help out only if all other employee groups join in and if the plan provides them "real financial returns".

So the prospects for securing concessions do not look promising at present. Some analysts suggested earlier that a Chapter 11 visit might be the only way for United to get meaningful labour concessions, but that seems a very unlikely scenario in light of the company’s strong liquidity position.

As a result, United is likely to continue to post losses longer than most of its competitors. The current First Call consensus estimate is a net loss before special items of about $1.2bn in 2002, followed by a loss of $462m in 2003.

On the positive side, the airline’s prospects have improved gradually in recent months, both in absolute terms and relative to the rest of the industry. Most significantly, it has steadily narrowed (and by now possibly even closed) the unit revenue (RASM) gap with competitors, after trailing the industry average by five points in the fourth quarter of last year.

The positive RASM trend may be largely due to vastly improved operational performance. United achieved all–time records in flight completion and on–time performance in May. The airline said that it was meeting all the new security checks with line waits almost back to normal. This is particularly important as surveys have shown that long check–in lines and airport hassles in general are discouraging potential business travellers more than fears about terrorism.

In the absence of labour cost savings, United has continued to press on with cost reductions in other areas. Most recently, it has closed 23 more ticket offices in and west of Denver, after already closing 35 offices across the country since September 11.

At the same time, however, United is adding flights in key business markets and hubs, particularly Chicago, which is seeing a 15% schedule expansion this month. It has an unbeatable route network and is determined not to lose market share to competitors, even though its system capacity will still be 16–17% below the year–earlier level in the current quarter.

United is taking a close look at whether the pre–September 11 business models still work in this new environment, particularly in view of a potential permanent reduction in business travel. A major effort is under way, under president Rono Dutta, to study possible changes in strategy, including seating configuration, legroom and possibly eliminating First or Economy Plus classes.