SWISS: New airline, old problems, different fate?

June 2002

SWISS — to be known as Swiss International Air Lines from July 2002 — is attempting the difficult task of combining short–haul specialist Crossair and large parts of the collapsed Swissair into Switzerland’s new flag carrier in a matter of months. Whatever its name, can a viable, profitable international airline survive long–term in Switzerland, or is the attempt doomed due to a combination of high structural costs and the country’s geopolitical isolation? The demise of Swissair is well–documented, but it’s instructive to recap the main reasons for its failure, to see which were specific to the airline and which were more structural, and thus relevant to the future of SWISS.

The SAir Group now owes SFr24bn ($14.8bn) to creditors — the exact amount is disputed — but it looks as if those creditors will be fortunate to retrieve more than 10%.

The fundamental cause of SAir’s spectacular demise was the disastrous "Hunter" strategy — the acquisition of stakes in other airlines and aviation service companies in an attempt to gain scale. As those companies failed to perform and no synergies were uncovered, SAir’s balance sheet was destroyed (see Aviation Strategy, February and April 2001, for example).

It tried to keep going under new management, but was forced into bankruptcy last October. It then revealed an audacious rescue plan whereby Crossair would purchase the worthwhile assets, Swiss banks and other institutions would supply new capital and the creditors would be left suing a shell company (Aviation Strategy, October 2001).

The Hunter strategy was presented as a solution to the classic problem of Europe’s mid–sized airlines. Swissair’s management didn’t want Swissair to settle for being a niche carrier, yet the airline was not large enough to be considered one of Europe’s major players, let alone a global force. The strategy was also seen as a response to two specific problems facing Swissair.

First, Switzerland was isolated politically. As a non–member of the EU, Swissair could only gain access to EU markets via a range of alliance deals, which were both difficult to negotiate and a serious distraction to management.

Partly as a result of this Swissair was more reliant on long–haul routes than most other European airlines. Yet Zurich was not a first choice entry point into Europe for North American passengers, and Swissair’s position in the Asia/Pacific market was undermined after SIA withdrew from the Global Excellence alliance in the late 1990s.

Second, Swissair also faced very high costs, from ground handling to labour. Despite management’s constant onslaught on costs in the late–1990s, through everything from job cuts to fleet harmonisation, Swissair’s unit costs always appeared towards the top of the European airline league.

The rebirth

Crossair took over Swissair’s short–haul routes after the latter’s financial collapse, although Swissair continued to operate longhaul flights for Crossair until March 31 this year, when SWISS was launched officially.

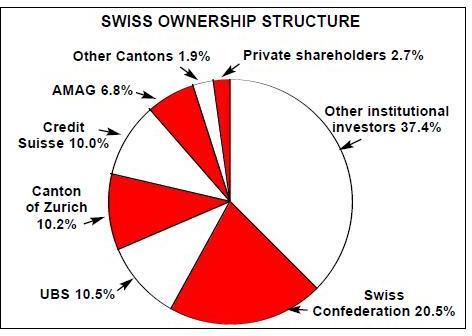

Financially, the emergence of the new airline from the ashes of Swissair was not straightforward and needed a large bridging loan from the Swiss government. The rescue plan, agreed last October, envisaged two–thirds of the new airline being owned by "corporate" investors and one–third by a combination of the Swiss Confederation (i.e. the Swiss state), local Cantons and City authorities.

This was achieved in two steps. First, at the end of last year UBS and Credit Suisse acquired 70.35% of Crossair from SAirGroup for SFr259m ($160m). Then earlier this year these institutions as well as other, new investors (such as Swiss Cantons and Cities) participated in a substantial capital increase in SWISS, at a total capitalisation of SFr3bn.

However, this process did face one upset when at the end of March the general public in Zurich voted against the City becoming a shareholder in the new SWISS, a shareholding that other SWISS shareholders assumed would be automatic. Although the majority was wafer–thin (51.8% against in a turnout of just 24% of the eligible electorate), an opposition of right–wing and left–wing parties successfully argued that the local authorities should not invest in a pure commercial enterprise — and in particular in a very risky one.

The other parties — including the Social Democratic Party and the Christian Democratic Party — argued that many jobs depended on a successful national airline. However, the Canton of Zurich (as opposed to the City) had already invested SFr300m in SWISS for a 10% stake, and local voters saw a SFr50m ($31m) investment, this time made by the City, as being one investment too many. In cash terms, the absence of the City of Zurich’s SFr50m was not a great concern for SWISS, but the decision of the City’s voters was embarrassing and begs the question: are the majority of Zurich’s citizens correct in believing an investment in SWISS is too risky in the long–term?

The strategy

Under André Dosé as its CEO, SWISS aims to fly 9.8m passengers in 2002, rising to 15m passengers in 2003 and making it one of Europe’s top–four airlines in terms of passengers carried.

Presently the airline serves 128 destinations in 59 countries, with 88 of those destinations being in Europe, 14 in Africa, 10 in the Americas, 9 in Asia and 7 in the Middle East. Swiss has a fleet of 133 aircraft, 26 of which are for long–haul (MD–11s and A330s, all coming from Swissair) and the rest for short–haul (of which 26 A319/20/21s came from Swissair).

For such a comparatively small airline there are too many aircraft types, although this is primarily the legacy of merging the Crossair/Swissair fleets. Fleet types will be reduced by the replacement of RJs and Saabs by Embraer 170s and 195s by 2006. The MD- 11s, all leased–in, will also be replaced by A340–300s by August 2004, an order announced in March this year. The future of the airline’s A330s is uncertain, as some SWISS executives are believed to be unhappy with the economics of the aircraft.

SWISS has more than 10,000 staff, of which 1,800 are pilots and 3,500 cabin attendants.

But half of these came from Swissair, so the inevitable question is: will Crossair’s lower cost base gradually be eroded? The first point to make is that although Crossair’s cost base was lower than Swissair’s, by no means could Crossair be regarded as a low–cost airline similar to easyJet or Go, simply due to Switzerland’s higher labour costs compared with much of the rest of Europe.

Second — and unsurprisingly — the ex- Swissair unions are wary of the new working conditions in SWISS. Ominously, at the end of 2001 Crossair and Swissair pilots argued about the integration of the Swissair pilots into the new airline, specifically the issue of seniority.

The matter was not helped by the Swissair pilots' union doubting whether Crossair should be the heir of the Swissair legacy given "recent events which have occurred in terms of safety" — an unsubtle and uncalled for reference to the Crossair crash in Zurich in November 2001.

Aeropers, the unions representing ex- Swissair pilots, eventually agreed to new terms with SWISS in late May 2002. The deal included a 35% reduction in salary compared with Swissair pay levels, although that may not be the end of pilot worries at the new airline as management wants to introduce one, unified set of conditions for all pilots. Crossair pilots are unhappy at this prospect and their union — Crossair Cockpit Personnel — insists the Aeropers/SWISS agreement has nothing to do with them.

Meanwhile in April ex–Swissair cabin crew rejected the initial collective working agreement offered by SWISS, while the flight attendants' union similarly rejected the terms proposed by the new airline, which included a 10% salary reduction. However, despite genuine worries about inferior conditions, militancy by the ex–Swissair workforce does not appear to be an issue and union members have agreed to keep working for SWISS until new agreements are finally agreed.

Overall, SWISS executives claim that costs are under control, and that losses for the first few months of the year are smaller than expected. Last year Crossair reported a loss of SFr314m ($194m), significantly worse than the SFr25m loss of 2000. Of the 2001 loss, more than 90% was due to the Swissair situation — specifically "debtor losses on credits with Swissair, obligations under the Qualiflyer frequent flyer programmes, reserves for outstanding legal actions and the loss of wet–lease revenues from 19 aircraft wet–leased to Swissair".

Crossair’s first quarter 2002 results are shown below, the last financials released under the Crossair name, although like the full–year 2001 results they are not a particularly relevant guide to SWISS’s prospects going forward, this time due to the substantial costs involved in integrating Swissair’s long–haul routes though the period.

The first full quarter results for SWISS — April to June 2002 — are expected to show a large loss, due to the costs of transferring longhaul routes from Swissair. Given these "start–up" costs, the airline forecasts its loss for 2002 to be around SFr1.1bn, based on revenues of SFr3.2bn. Turnover should hit the SFr5bn mark in 2003, the airline believes, allowing break–even that year. Since fuel and currency risks have been hedged — according to management — the main remaining external risk to recording a profit in 2003 would be another terrorist incident along the lines of September 11.

Is break–even achievable in 2003? SWISS’s strategy of consolidation rather than expansion for the short- and medium–term is sensible, and the focus has to be on integrating the ex–Swissair long–haul routes and making them profitable again. Of great assistance here will be pruning of capacity — at the moment SWISS’s ex–Swissair routes have 30% less capacity than Swissair operated — as well as the alliance with American announced at the end of March. SWISS now has an AA code on transatlantic flights from Zurich to New York JFK, Newark, Boston, Washington, Chicago, Los Angeles and Miami.

This may be the first step towards SWISS joining oneworld — although this will require bilateral alliances with all oneworld members. And if specific long–haul routes do not hold out the prospect of breaking even within a reasonable period then SWISS’s management needs to be ruthless and cut them — the type of difficult decision that Swissair’s executives were incapable of making.

Cash is king

However, in the short–term it is the availability of cash that will be the key determinant of how well SWISS will fare. At the start of 2002 Crossair/SWISS had SFr700m in cash, which was boosted by another SFr1.9bn from the share capital increase earlier this year.

SWISS forecasts a year–end cash position of SFr500m after aircraft purchases and other investments that are expected to drain SFr1bn from cash reserves through 2002. Comparing the year–end and start of year cash figures, this means the airline will have a hefty SFr92m ($57m) net cash outflow each month in 2002, due largely to operating losses and changes in working capital.

Although the cash burn will not be linear, at this rate Swiss would run out of cash sometime in June 2003. That’s just 12 months from now, which means that there is little room for error in SWISS’s strategy — unless, of course, management believes that investors will dip into their pockets again when needed, as they did for Swissair?

Assuming that’s not the case, the survival of SWISS will depend on its quality of management. Interestingly, Moritz Suter — the founder of Crossair — resigned as head of airline operations at SAirGroup in early 2001 due to resistance to his ideas for transforming the airline from SAirGroup and Swissair executives.

Suter is reported to have been dismayed by poor management at Swissair and decisions such as making major investments into carriers such as Sabena and various French regional airlines. Yet Suter was denied a seat on SWISS’s board as he was regarded as being unpalatable for many of SWISS’s new investors — a decision that hopefully is a one–off political expedient rather than an indication of a long–term drift towards the type of safe, "conservative" management that got Swissair into such trouble.

More encouraging is the fact that not many ex–Swissair managers have been taken on by SWISS as the new airline attempts to establish a culture and level of professionalism of its own.

As for the SWISS brand, the new airline is undoubtedly seen by many passengers as being Swissair under a slightly different name and livery, so SWISS will get all the positive (and negative) brand attributes that previously belonged to Swissair. How much damage the Swissair brand in 2001 suffered as the airline collapsed is a matter of opinion, but at the very least passengers will assume that the new SWISS is similar to Swissair in that it is a major airline offering short- and long–haul routes, and is associated with "quality" service and products.

Since SWISS is aiming to win a large slice of the point–to–point European business travel market, brand crossover from Swissair is valuable, and a completely "new" start–up airline would have had to spend considerable amounts of money on establishing an image.

The future

So will the airline survive? In the short–term, sensible operational and financial targets (such as a forecast 48% load factor for 2002 — a target that SWISS will beat comfortably) will keep investors onside, but long–term success will depend on how management reacts once the consolidation period is over.

The temptation to expand routes and services will be hard to resist, particularly if management believes another slice of cash will always be available from investors if forecast profitability in 2003 proves elusive. It would be all too easy to be panicked by an inevitable increase in competition — easyJet Switzerland, for example, is increasing frequencies and routes — but SWISS’s stranglehold on slots at Zurich airport is a substantial advantage.

The key period for the airline is likely to be towards the end of 2002. That’s when management will have a reasonable run of data on which ex–Swissair routes are profitable and which are not. If management takes some tough decisions at that point, so that cautious route expansion is also accompanied by selective pruning of the timetable, then long–term survival is possible. But if SWISS hopes to gloss over continuing core losses by aggressive expansion accompanied by another capital expansion, then a fate similar to that of Swissair may await.

| Fleet | Orders | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A319 | 7 | ||

| A320 | 11 | ||

| A321 | 8 | ||

| A330 | 13 | ||

| A340 | 13 | Delivery in 2003-04 | |

| MD11 | 13 | To be replaced by A340s | |

| MD83 | 9 | ||

| RJ85 | 4 | To be replaced by Embs | |

| RJ100 | 15 | To be replaced by Embs | |

| Emb145 | 25 | ||

| Emb170 | 30 | Delivery in 2002-05 | |

| Emb190 | 30 | Delivery in 2004-06 | |

| Saab 2000 | 28 | To be replaced by Embs | |

| TOTAL | 133 | 73 |

| Revenue from scheduled pax. | 446 |

| Other operating revenue | 71 |

| Operating revenue | 517 |

| Operating expenditure | -699 |

| EBIT | -182 |

| Financial items | -5 |

| Tax | -3 |

| Consolidated loss | -190 |