El Al: Fall-out from the intifada

June 2001

The latest Palestinian intifada has set back the finances of Israel’s state–owned airline El Al and raised a very serious question mark over prospects for its privatisation.

The intifada, which began last September, has sent Israeli tourism figures plummeting and with them passenger figures, revenues and profits for El Al. The company will shortly confirm a huge loss for last year while a drastic restructuring is being implemented. At the same time it is having to cope with increased competition in its domestic and international markets.

The current Israeli administration of Ariel Sharon is continuing the privatisation programme of previous governments and last month invited bids for Bank Leumi, the second largest bank in Israel, and the outstanding government holding in Zim Israel Navigation, formerly the country’s national shipping line. Plans to sell an initial 49% stake in El Al via a flotation on the Tel Aviv stock exchange, however, will have to wait a little longer.

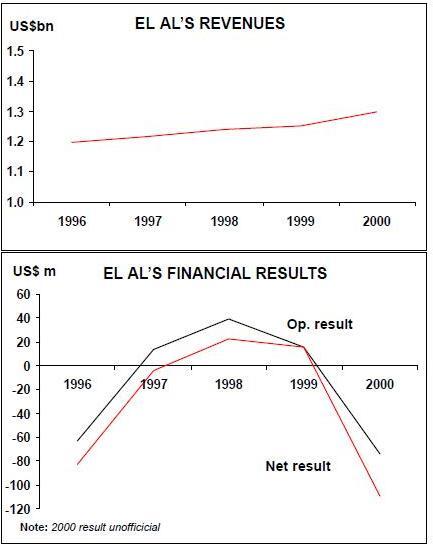

El Al has been a candidate for privatisation for at least a decade but in that period it has had to contend with both tourist–daunting outbreaks of violence and a more volatile domestic political scene, with changes in the Israeli government becoming more frequent. In previous periods of relative stability in the region El Al appears to have been profitable, but that was when it was still protected from internal and external competition. In the late 1980s, for example, it posted operating profits of $25–30m and net profits of $15–23m on revenues of around $700m just before the Gulf War broke out and sent tourism figures plunging again. In 1995 it made an operating profit of $35m and a net profit of $15m and in 1998 an operating profit of $38.7m and a net profit of $22.7m when revenues were in excess of $1.2bn.

Last year, however, the airline made a net loss of $109m and an operating loss of $74m on revenues of $1.3bn, compared with a net profit of $16m, operating profit of $15.6m and revenues of $1.25bn in 1999. El Al will officially announce its results for 2000 in June when its annual report is published but the headline figures have already been leaked (no doubt for political reasons) and confirmed by El Al management. The official results are expected to confirm the sharp fall in passengers for the last three months of the year, an 80% increase in fuel expenditure despite some hedging and a $35m loss on financial items. El Al is in the middle of an extensive fleet renewal, having committed itself to the $330m purchase of three 777- 200s from Boeing (an option for a fourth is still being considered), in addition to five 737–700s delivered in 1999. Long–term loans at the end of 1999 stood at $627m.

Recovery plan

To deal with the intifada effect and other factors, El Al management has put in place a recovery plan which has as its main features a fleet restructuring, the closure or suspension of routes, at least 500 redundancies among its 3,500 worldwide staff and a greater emphasis on high–paying customers. It will also seek to develop more Asian routes (it has a code–sharing agreement with Thai Air) and increase cargo revenues by exploiting capacity on passenger aircraft.

The airline is also in discussions with the Israeli government on acquiring a 25% stake in Arkia, the privately–owned Israeli charter and regional airline, with a view to utilising it in conjunction with El Al subsidiary, Sun D'Or, as a low–cost arm. Arkia seems to be in favour of greater co–operation with El Al as it too has suffered badly from the slump in traffic since the intifada began.

The fleet restructuring will see El Al concentrating operations on its four fleets of 747–400s 737–700s, 777–200s and 767s. The aging fleet of 747–200s and an as–yet unspecified number of its 757s are to be sold or leased off. El Al sees the reduced fleet as helping reduce its fuel and maintenance bills, while a greater emphasis, including a $15m upgrading programme, will be placed on first–class and business–class passengers rather than tourists. Ten routes are to be cancelled or suspended with Manchester, Copenhagen, Nairobi, Minsk, St Petersburg, Simferopol and Dnepropetrovsk being dropped this year. The last four routes are a reminder of how El Al throughout the 1990s built up an extensive network of routes throughout the Former Soviet Union, partly holiday destinations such as Simferopol on the Black Sea and partly as a result of the return to Israel of Soviet Jews.

Many of these routes were flown by El Al’s charter subsidiary, Sun D'Or (sometimes in conjunction with Arkia), and subsequently converted into El Al scheduled flights. (Sun D'Or had revenues of $25m in 1999, compared with $31.4m in 1998 when its FSU operations were included and contributed $1.3m to El Al’s 1999 consolidated results.)

El Al’s operations in the US where it is a 24.9% shareholder in North American Airlines, which operates transcontinental services connecting to El Al’s flights in New York, are also to be scaled back. According to one report, within El Al’s plan to reduce its overseas expenses by $6m the biggest cut at 30% will be in the US budget, with redundancies, office closures and route restructuring. El Al has recently signed a code–share agreement with Delta in addition to an existing one with American, which could facilitate the route rationalisation.

The new competition

Before the present crisis began El Al appeared to be making progress towards the kind of profitability that would make its privatisation more likely, although there were signs it was beginning to feel the effects of greater competition. The "peace dividend" was having a beneficial effect but El Al was having to share them with both domestic privately- owned charter airlines Israir and Aeroel, as well as Arkia and foreign airlines, scheduled and charter. Increased competition in freight operations following the granting of a licence to Cargo Airlines Ltd at Ben Gurion also undermined El Al’s dominant position in this sector.

Even so El Al’s passenger numbers in 1999 rose to more than 3.1 million from the previous year’s 2.9 million and revenue exceeded $1.25 billion. A 17.7% increase in fuel costs, however, helped drag the operating profit down from $38.7m in 1998 to $15.6m, while heavy financing costs of El Al’s new aircraft resulted in a loss of $15.4m. El Al, however, raised $25.2m from the sale of shares in Equant, which, with contributions from subsidiaries and other gains, helped to produce a net profit of $16m.

While El Al was having to live with increased competition, this was not seen as the biggest obstacle to partial privatisation. Instead, the airline and some sympathisers in the government believed the biggest obstacle was the government–imposed ban on El Al flying on the sabbath and other Jewish holidays, a handicap with which it has had to live since 1982.

The sabbath ban

The sabbath ban (beginning on sundown on Fridays) limits El Al to operating for only five and a half days a week. The airline says it "significantly impacts the company’s competitiveness and damages its position in the market with potential partners and also materially affects its value, revenues and profitability". It estimates the ban costs it $50m a year in revenue and Israeli analysts have been quoted as estimating the ban’s effect to be to knock $90–220m off the airline’s value (a figure of $250–300m was touted around prior to the current crisis).

Whereas in the past El Al used to make a virtue out of the ban by claiming it was still profitable despite being a "5 1/2 days–a-week carrier", the more recent approach has to be lobby for a repeal of the ban and to seek compensation for the lost revenue. A government committee was set up in 1999 to review the ban, particularly in light of the opening–up of Israel’s aviation market to seven–days–a week–carriers, and last year the then prime minister, Ehud Barak, appeared to come out in favour of lifting the ban. This, however, prompted threats of resignation from cabinet ministers appointed from the ranks of less liberal minority parties in Barak’s coalition. Barak was replaced in February this year by the more right–wing Ariel Sharon who is publicly less disposed to such liberal tinkering with religious laws.

One way around the ban, it has been suggested, would be for El Al to route as much of its traffic as possible through Arkia which, as a privately–owned company, is not subject to the ban and with which El Al would be merged. (Arkia, set up by El Al and the Israeli labour organisation, Histadrut, in 1949, was in 1980 the first state–owned company to be privatised and had been rapidly expanding prior to last year.)

El Al is also claiming compensation from the government for the extra security costs it has to bear as the national carrier. In 1999 it estimated these at $6.2m and added a further $2.4m for revenue lost due to the carriage of security personnel. They form a minor knot in the tangled mess of claims and counter–claims between El Al and the government which has to be disentangled prior to privatisation. Chief among these are "usage fees" which stood at $267m in 1999 and cover aircraft owned by the government and "leased" by El Al; outstanding severance pay liabilities of $173m (as at end- 1999) relating to the company’s period in receivership and to be financed by the government; and El Al’s accumulated losses, which had reached $212m by the end of 1999.

Tortuous relationship with government

The burden of being the Israeli national carrier (religious observation, higher security), the pressure from increased competition created by its own government and frustration at political interference in strategic decision- making have helped to make relations between airline management and government strained, with the former accusing the latter of having no coherent aviation policy.

Last year Joel Feldschuh, El Al president and CEO, resigned after four years, a move attributed to the pressures of dealing with the then government. El Al was negotiating with Airbus for the purchase of three–to–four A330–200ERs at the time but was eventually persuaded to stay with Boeing, despite the fact Airbus made, according to El Al, an "attractive offer" (El Al had paid a refundable $700,000 deposit). Feldschuh was replaced by David Hermesh, who was recruited from the Israeli private sector.

The current financial crisis at El Al has done little to improve relations with the government, although the latter appears not to have directly interfered with the recovery plan. The privatisation minister, Yaron Jacobs, was quoted in the Israeli press claiming El Al would run out of cash by the end of the year and warning the airline may have to be placed back in receivership. El Al management has denied this extreme measure will have to be taken.

Receivership was used in 1983 as a drastic remedy for the airline’s chronic labour problems of the 1970s when strikes were a regular feature and evidence of the stranglehold the then powerful Israeli trade union movement had on the airline. El Al was shut down for four months to enable the management to regain control and sign a new labour agreement. The airline resumed operations with a cost–cutting programme of redundancies and retirements. The workforce was gradually cut back from 6,000 in 1979 to 3,600 a decade later. Another decade on and with the company no longer in receivership, the El Al unions seem, in the face of the current financial crisis, to have accepted the need for further redundancies without too much resistance.

El Al’s dilemma arises from its position as the high–profile symbol of the Israeli state. The influence of its unions, particularly the pilots with their links into the airforce, further complicates matters. Its role in promoting and facilitating Israeli tourism means it is always going to be vulnerable to sharp fluctuations in passenger traffic as long as the Middle East remained a volatile region. It is not surprising, then, that as part of the restructuring El Al management is focusing more on business travel than tourism.

The problem of the sabbath ban is less simple to resolve. If the Israeli government were to proceed with the 49% sale, it would have to decide whether it could afford to do so with the ban still in place. Repealing the ban, on the other hand, may involve a more considered calculation of the political risks involved, while continuation of the ban under state ownership exposes El Al to the risk of greater losses and hence the need for more government support.

The "Arkia option" then begins to have a certain attraction, although the more orthodox Jews might not be easily persuaded and Israel’s other airlines may have grounds for complaint. With violence in Israel continuing at the time of writing, there seems little prospect of Israeli tourism recovering in the immediate future. How much this will continue to hurt El Al even as it upgrades itself to a business–class airline may not be as important as how many days a week a week it can fly.

| In operation | On order | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 737-700 | 2 | ||

| 737-800 | 3 | ||

| 747-200 | 3 | ||

| 747-200F | 4 | ||

| 747-400 | 4 | ||

| 757-200 | 6 | ||

| 767-200 | 6 | ||

| 777-200ER | 3 | 3 | Not yet confirmed by Boeing |

| Total | 31 | 3 |