United: the fundamental labour problems

June 2000

Is United wise to take on US Airways in light of its extremely challenging labour situation? While United has continued to outperform the industry financially, it is now probably the worst–positioned among the US carriers on the labour front. It has to secure new contracts with most of its employee groups and faces a substantial hike in labour costs, due to the ending of its employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) between April and July this year.

The contract negotiations have turned out to be much more difficult than was initially expected, which makes it surprising that UAL’s leadership is prepared to further complicate the situation with the integration issues posed by the merger.

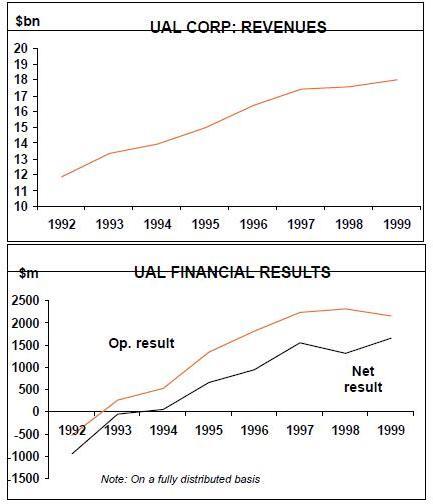

UAL has continued to report record earnings, thanks to exceptionally strong domestic unit revenue growth and a recovery in Asian markets. For the March quarter, the company posted increases in operating, net and per–share earnings (before extra–ordinary items) on both GAAP and fully distributed basis, despite 34% higher average fuel prices.

In fact, UAL’s operating earnings before one–time charges set a new first–quarter record at $384m or 8.4% of revenues on a fully distributed basis. Net earnings before special items rose marginally to $191m. This followed record net earnings of $1.7bn reported for 1999.

UAL’s earnings have risen strongly and steadily since profitability was restored in 1994. Some $5.2bn worth of concessions granted by the workers in 1994 in exchange for a 55% ownership stake, as well as relative labour stability, have been instrumental.

The latest results reflect very favourably on UAL’s top management, in particular James Goodwin, who took over as chairman and CEO when Gerald Greenwald retired in July 1999. Goodwin has surprised everyone with his leadership skills and bold initiatives, which have included helping to retain Air Canada in the Star alliance, introducing a new domestic "Economy Plus" product and aggressively developing United’s e–commerce strategy.

The earnings stability has paved the way for UAL to restore regular dividends this month after a 13–year gap, making it the only major carrier to pay proper dividends (Delta and Southwest pay nominal amounts). Also, after buying back $750m worth of its common shares in 1997–99, another $300m share repurchase programme is under way.

UAL stockholders will receive 31.25 cents per share on June 15 in the first of what looks likely to become quarterly payments. The move, which could broaden UAL’s shareholder base, is unlikely to be copied by other carriers as dividends are normally a tax–inefficient way of returning cash to shareholders. But dividends paid to an ESOP receive favourable tax treatment, which United indicated would result in considerable savings. An added benefit is to be able to appease employee–owners at a time of contract talks.

Strong cash flow and equity boosts have strengthened UAL’s balance sheet, after it was significantly weakened by the recapitalisation associated with the ESOP. However, the proposed purchase of US Airways, which includes a $4.3bn cash payment and assumption of $1.5bn of debt and $5.8bn of off–balance sheet leases, would substantially weaken UAL’s balance sheet. At year–end the company had $16.5bn of debt and leases. S&P, which immediately placed UAL’s ratings on "credit–watch negative", estimates that the deal would raise debt–to–capital ratio from 71% (year–end 1999) to around 81%.

Strong unit revenue growth

UAL estimates that full–year 2000 earnings will fall to $8-$10 per share before special charges from the $10.06 per share earned in 1999, mainly because of the ending of the ESOP. Analysts currently believe that the results will be at the high end of the range. However, these estimates assume that the pricing environment will continue to be strong and that the post–ESOP wage increases can be kept within the management’s targets. One of United’s greatest strengths at present is its remarkably strong revenue performance. A stunning 10% surge in March boosted unit passenger revenue growth to 5% in the first quarter, at the expense of only a marginal fall in load factor, and another 7- 8% rise is expected for the current quarter and 4.5–7% for the year.

Domestically, the carrier has outperformed the industry, which is partly attributed to a new revenue management system, the Economy Plus product and constrained capacity addition. Economy Plus, which entailed re–configuring almost the entire domestic fleet to provide five extra inches of legroom for full–fare passengers and some frequent–flyers, is estimated to boost domestic RASM by two percentage points this year, though unit costs will also rise because of the associated capacity reduction.

Impact of ESOP ending

Continuation of strong domestic RASM trends is, of course, far from certain, but United is now also benefiting from accelerating unit revenue growth in all of its international regions. Most significantly, Pacific unit revenues have risen for three consecutive quarters (6% in the latest period), while Latin America has been running at around 8%. Even transatlantic unit revenues rose by 3% in the March quarter — the first improvement in over a year as industry capacity growth moderated. But the revenue gains may be more than offset by a surge in labour costs this year as the ESOP comes to a close. The process began in April, when the wages of pilots and most other ESOP employees snapped back to the pre–August 1994 levels. The machinists' ESOP contract will come to a close on July 12.

The ESOP does not actually "expire", in that in February United’s employee–owners and management decided to "freeze" it at its current state. Instead of creating a new ESOP at this stage, employees will get pay increases. The practice of allocating more UAL stock into employees' accounts in a trust will cease, but workers will still receive the previously allocated shares when they retire or leave the company. If there is no new ESOP, employee ownership at United will wind down gradually over a few decades.

Renewing the ESOP in some modified form has been a possibility, but according to United’s CFO Doug Hacker, there is little appetite for that at present (a comment made before the merger announcement). The pilots have made getting a contract their first priority, but they continue to be potentially interested in an ESOP after the contract is secured. There is apparently significantly less interest among other employee groups.

A new ESOP is probably the lowest of all priorities at present in light of the US Airways merger announcement and the likelihood that the contract talks will, as is typical, drag on for months or even years.

The wage snap–backs are only a small part of the problem (the pilots' pay went up by just 6.7% in April when the ESOP ended). The biggest problems are that the 1994 pay rates are obviously substantially below competitors' rates and that the pilots are now demanding industry–leading wages. According to ALPA, a United 777 captain is now paid 28.5% less than a Delta 777 captain.

United says that it is fully committed to restoring competitive wages to its workforce after the ESOP, as outlined in its "Vision 2000" plan. But its April offer of 13.4% over the 1994 level was a long way off the 25- 30% demanded by the pilots. The gap also remains wide on benefits, job security and the use of regional jets. The current scope clause allows only 65 RJs with a maximum of 50 seats, which puts United at a competitive disadvantage with carriers like American and Delta.

Both sides originally expected much smoother talks and certainly a new contract by the April 12 deadline. They have been negotiating since December 1998. The company also took great care to ensure that Gerald Greenwald’s succession would not become an issue with the unions. In September 1998 former president/COO John Edwardson stepped down when it became clear that the heads of IAM and ALPA would not support him to succeed Greenwald. And James Goodwin was strongly supported by the unions and is popular with the workers.

Also, despite the ESOP coming to a close, the unions have retained their board seats and veto powers over major decisions, because the governance principles are written into the company’s charter. Labour contract and stock ownership negotiations are regarded as entirely separate processes. The impression gained is that the management is prepared to live with the existing governance structure in the hope of maintaining labour stability.

But the pilots' patience is beginning to wear thin. While there is no threat of strike or other organised work action, over the past month some pilots have been refusing to fly "overtime" in protest over lack of progress in the contract talks. This led to some crew shortages and spates of flight cancellations in May, though the situation was exacerbated by poor weather conditions. The company is now recruiting more pilots in an effort to eliminate the problem, and the contract talks are due to resume under federal mediation in early June.

The pilot representative on UAL’s board was the only director to vote against the merger on May 23. On June 2, after three days of meetings with the management, ALPA announced that it could not support the deal "as it is presently structured". The main problem is seniority integration, as US Airways has a much larger percentage of senior pilots than UAL has.

According to ALPA, Goodwin told them that he had pressed for measures to protect United pilots' seniority in the merger talks, but US Airways chairman Stephen Wolf did not want the deal to be contingent on any labour issues. This is obviously hard for the pilots to accept, given that UAL is the acquirer. Also, it can only add to the grievances that United pilots have about being left out of the decision–making process and not being treated with the respect that employee–owners deserve.

Nevertheless, the pilots' carefully worded statement left the door open for negotiation. Interestingly, according to the union, in the context of the merger presentations Goodwin pledged to give the pilots an "industry–leading" contract.

The pilots will not be able to veto the merger because the IAM representative on UAL’s board voted for the deal. But in practice United needs its pilots' approval for the merger to have any chance of success.

It is not yet clear if the merger issues will be dealt with in the context of the contract talks. If so, they will divert attention from tough existing issues, such as RJs, and prolong the negotiating process.

As a result of the ending of the ESOP, United expects its salary costs to rise by 12% in the current quarter, after a mere 1% increase in January–March. Unit costs are expected to surge by almost 10% (or 7% excluding fuel). The ESOP cost impact for 2000 is estimated at $780m (or $1.3bn on a full 12–month basis, according to Merrill Lynch). But those estimates are based on what United’s management believes are competitive wages, rather than what the workers will accept.

Aggressive e-commerce

Because UAL submitted the ESOP impact estimates to the financial community several months ago, the labour cost factor is believed to have been fully reflected in its share price for a while. Until the US Airways merger announcement, many analysts included UAL among their "top picks" on grounds of low valuation and longer–term growth potential. Of course, the prevalent advice now is caution until the overall consolidation picture clears. According to a recent survey by Salomon Smith Barney, United is ahead of its competitors in terms of stakes held in Internet ventures. This gives it enhanced potential for cashing in on non–core assets in the future.

CFO Doug Hacker suggested recently that one way to make shareholders happier might be to spin off disaggregate e–commerce ventures, thus isolating the benefits that could be more specifically targeted to particular types of investors.

More immediate plans, however, involve the creation of an e–commerce subsidiary, staffed by employees from United’s marketing and technical divisions and located outside its headquarters, to enable it to better sell travel products on the Internet, as well as to manage its partnerships and relationships with online travel sites.

International growth plans

United is also spending $8-$10m to improve its web site, to help double this year’s Internet sales from the $500m or 4% of total sales achieved last year. The goal is to boost Internet sales to "at least 20%" of revenues by 2003. United is in the middle of an international expansion drive, focusing particularly on Los Angeles which was designated as a domestic hub a year ago. San Francisco, the more established international hub, has seen restoration of many Pacific services as the Asian markets have recovered. After Shanghai and Seoul, Beijing and Frankfurt are due to be added later this year.

Next year’s plans envisage a daily nonstop "air bridge service" linking both San Francisco and Chicago with Beijing and Shanghai, thus eliminating the Tokyo stop. United also expects to become the only carrier to operate a round–the–world service, linking Washington DC, Los Angeles, Hong Kong, Delhi and London.

United’s Pacific capacity, which is still well below the pre–Asian crisis peak level, is expected to surge by 11.5% this year, and more growth will follow in 2001. This year’s estimated 8% transatlantic ASM growth is much higher than previously anticipated because of a new San Francisco–Frankfurt service. But a planned 10% reduction in Latin American ASMs will moderate this year’s total international capacity growth to a little over 7%.

United has been quick to develop cooperation with new Star alliance entrants like Austrian. It has a well–established alliance with Mexicana, which will join Star in July, and is keen to cooperate with British Midland (due to join later this year) and Lufthansa at London Heathrow. United’s main interest in a potential US–UK "mini–deal" is the opportunity to "mount collectively quite an attractive Heathrow operation with our Star partners".

Domestic network

However, Star is clearly not a priority for United, which contrasts with Lufthansa’s considerable efforts to coordinate the alliance. This probably largely reflects the fact that international services are a much bigger part of European airlines' total operations. United expects its domestic capacity to increase by just 0.5% this year, in part because of the seat removals associated with Economy Plus. Because of this, system capacity will rise by around 2.8%, which would be below the industry average. Growth will accelerate from zero in the first quarter to up to 6.5% in the fourth quarter.

Having established strong hubs at Chicago, Denver and San Francisco, much of United’s effort over the past year or so has focused on building up domestic hub operations at Los Angeles and Washington Dulles. The Los Angeles expansion, which has been in response to strong demand and AMR’s acquisition of Reno and new code–shares with Alaska, has included increased frequencies to Dallas, Houston, Atlanta and cities on the East Coast.

In early 1999 United decided to start strengthening it presence on the East Coast -"the one piece of our very strong US and international route network that is not yet in place". This has included a rapid build–up of long haul and feeder services at Washington Dulles — a process that has inflicted much localised damage on US Airways but has given United only a limited foothold in the region.

The main reason behind UAL’s bid for US Airways is to effectively fill the East Coast gap and to gain an edge over American (rather than respond to Delta, Continental, Southwest and others that are also expanding rapidly on the East Coast). Its mainly east–west route structure provides a "perfect strategic fit" with US Airways' East Coast north–south operations.

United is at least publicly confident of securing regulatory approval for the merger. However, it seems likely that more concessions will be necessary to allay anti–trust concerns.

In the event that the merger is approved, the long term benefits to United — through East Coast revenue generation, hub consolidation and fleet commonality — could substantially offset the higher labour costs and financial obligations. According to a recent report from Merrill Lynch, United estimates that the acquisition would dilute per–share earnings by 35% in year 1 (2001) but boost earnings by a similar amount in year 2.

Should the merger not materialise, United actually has some promising growth opportunities at Chicago, its main hub and home base, as slot controls there are phased out over the next two years. Although competitors will obviously also benefit, trends at other dual–hub airports like Dallas Fort Worth have shown that over time the number one hub carrier gains market share at the expense of the number two (American at Chicago) and others.

| Current fleet | Orders | Remarks | |

| (options) | |||

| 727 | 75 | Stage 3 | |

| 737-200/300 | 125 | Stage 3 | |

| 737-500 | 57 | ||

| 747-200 | 9 | ||

| 747-400 | 43 | 1 | Delivery 2000 |

| 747SP | 1 | ||

| 757-200 | 98 | ||

| 767-200/300 | 53 | 3 | Delivery 2000-01 |

| 777-200 | 41 | 20 | Delivery 2000-01 |

| DC-10-10/30 | 17 | ||

| A319 | 29 | 22 | Delivery 2000-02 |

| A320 | 59 | 32 | Delivery 2000-02 |

| Total | 607 | 78 |

| Employee | ||||||||

| 1999 | 2000 | Change | 1Q | 2Q | 3Q | 4Q | ||

| Group | ||||||||

| Pilots | 1,520 | 1,900 | 380 | 127 | 127 | 127 | ||

| Ramp and customer | ||||||||

| contact workers | 1,316 | 1,500 | 184 | 92 | 92 | |||

| Mechanics | 909 | 1,000 | 91 | 45 | 45 | |||

| Admin and management | 598 | 700 | 102 | 51 | 51 | |||

| Non-ESOP Groups | 1,386 | 1,400 | 14 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Total 2000 vs 1999 | 5,729 | 6,500 | 771 | 127 | 322 | 322 | ||

| Total 2001 vs 1999 | 1,288 | 322 | 322 | 322 | 322 | |||

| Source: Merrill Lynch |