Cathay Pacific: redefining its role

June 2000

Cathay Pacific has survived the Asian crisis, returned to profitability and is again expanding rapidly. Now it has to re–define its role as a global Chinese carrier based in the Special Administrative Region (SAR) that Hong Kong has now become.

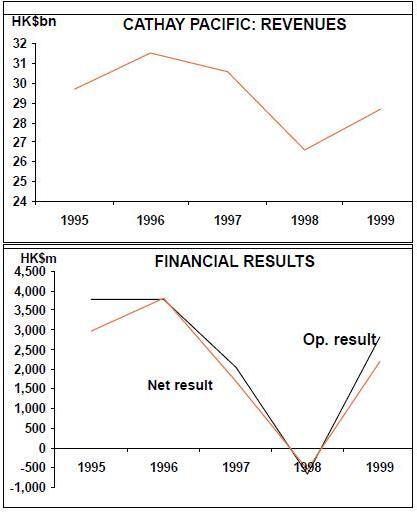

1998 was a nightmare year for Cathay Pacific executives. The Asian crisis struck hard just after the hand–over of the former British colony to PRC, and Hong Kong GDP fell by 5.9%. The collapse of intra–Asian business traffic, the drying–up of tourism from Japan and scares about chicken flu caused traffic to stagnate while yields dropped by 20%. For the first time since 1963 the airline produced a net loss, HK$542m (US$70m).

1999 saw a rapid return to profitability as economic growth resumed at around 2.5% (6–8% is expected for 2000). Revenues increased by 7.8% to HK$28.7bn ($3.7bn), costs fell by 2.3% to HK$26.5bn and net profits of HK$2.2bn ($285m) reappeared. For this year Deutsche Bank in Hong Kong is expecting a net profit of HK$3.6bn.

Turn-around elements

The share price has recovered as well. Having traded at a substantial discount to net asset value in 1998 and part of 1999, the airline has now got a stock–market valuation of HK$47bn ($6.2bn), nearly 20% above that of its oneworld partners, American and British Airways. Deutsche Bank’s target price for Cathay’s shares in 2000 is HK$17.4 compared to HK$14 at mid–May. Cathay’s turnaround strategy was based on a 3.6% reduction in capacity which, combined with a 1.9% recovery in traffic, pushed passenger load factors up to 71.5%, a level not seen since the early 90s. At the same time the decline in yield was stabilised. The capacity cutbacks were concentrated on Japan, Southeast Asia and Australia, while European and US services were maintained at previous levels.

The Asian export boom was the second most important factor in Cathay’s recovery. Cathay Pacific Cargo’s fleet of six 747Fs was fully utilised (80% load factor), as were the three 747Fs of Air Hong Kong, a 75%- owned subsidiary, and additional capacity had to be chartered in from Atlas Air.

With both volumes and yields well up Cathay’s cargo revenue increased by 23% in 1999. Freight now accounts for nearly 30% of Cathay’s business compared to 20% in the mid–90s. The cargo growth rate will inevitably slow this year as Asian currencies regain some of their value and export prices rise, but Cathay is committed to expansion in this sector, and the SAR is generally supportive of a liberal cargo regulatory regime. Two more 747–400Fs will be added to the fleet this year.

Interestingly, Cathay’s alliance links in the cargo market are with Lufthansa. It is now in its eighteenth year of joint operation on the Frankfurt–Hong Kong route, and it has recently signed an extensive agreement with DHL, 25% owned by Lufthansa, to carry express freight in the bellyholds of its passenger aircraft through the Southeast and Northeast Asian regions.

The Asian crisis forced management to confront its labour problems, including the ex–pat cost structure of its cockpit crews. This has not been achieved without pain — there was a two–week pilot strike last summer. Nevertheless, staffing levels were cut back sharply from pre–Asian crisis levels by about 2,500 employees or 16%. Labour costs fell by 8% in 1999 and further gains are still to come through. Cathay now claims that its productivity (ATK per employee) is equal to that of SIA.

Cathay has also attacked travel agent commissions in a big way — these were down by 7.5% in 1999, and should fall further as the airline moves further into electronic distribution and e–commerce. Landing and parking charges at Chep Lap Kok will be reduced this year as the airport authority cuts charges by 15% in January in an effort to promote the competitiveness of the new airport.

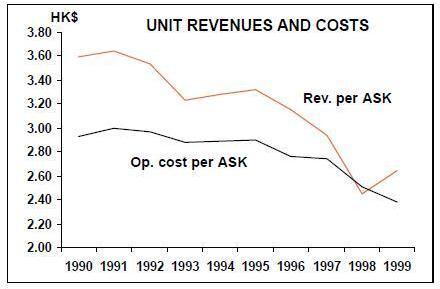

From 1990 to 1997 Cathay Pacific almost doubled its capacity but unit costs scarcely moved. As a result the airline’s profitability was being squeezed well before the Asian crisis brought a precipitous fall in unit revenues. In effect, the Asian crisis has given Cathay the opportunity to halt this trend.

The other element in Cathay’s recovery plan was its entry into the oneworld alliance in the autumn of 1998. In our previous briefing on Cathay (September 1998) we commented on the fact that Cathay executives had carried out the network analyses on various alliance options and concluded that the bottom–line benefits were not at all tangible. Still, Cathay’s commitment to oneworld was quite understandable given the miserable trading conditions that the airline was facing at that time.

There are still genuine question marks over how Cathay can develop this alliance.

First, Cathay finds itself in fierce competition with the code–shared Qantas/BA service between the UK and Australia. Cathay for its part is highly unlikely to be allowed to code–share with either of these oneworld carriers on either Hong Kong–Australia or UKHong Kong. The Australian Competition Commission has already expressed concern about possible collusion on this trunk route.

Cathay’s code–shares with BA are limited to the UK domestic shuttles (Heathrow to Glasgow, Belfast, etc., which were formerly British Midland code–shares).

Second, the Hong Kong authorities failed to win code–sharing rights for Cathay in its US bilateral negotiations early this year. The aim is for Cathay and American to code–share on Hong Kong–US, intra–Asian and some US domestic services, but at present Hong Kong will not accede to US requests for increased fifth freedoms over Hong Kong.

Third, the single oneworld code–share that was proving useful to Cathay was Hong Kong to Vancouver and Toronto, but that will end in June following the absorption of Canadian into Air Canada and Star.

Fourth, there is uncertainty over the alliance preferences of Cathay’s Chinese partners. Dragonair has decided against joining oneworld and China Eastern is considering all its options at present.

In the 1999 annual report Cathay’s chairman James Hughes–Hallett seemed to be slightly low–key on the benefits of oneworld, simply noting that "solid progress" has been made. In alliance terms, Cathay probably needs American as a partner because US carriers generally are looking to expand swiftly into the Hong Kong and Chinese markets following China’s admission to the WTO earlier this year.

But there are conflicts of interest with BA and Qantas, which might swing Cathay towards Swissair, with whom it used to have a code–share, bringing it into the new American/SAir/Sabena grouping. Cathay also has a code–share and FFP links with South African Airways, which is partly owned by SAir.

New expansionism

Like SIA, Cathay appears ambiguous towards global alliances preferring the bilateral alliance model in many instances. Whether or not it switches from oneworld to American/SAir, it will certainly maintain its close cargo agreements with Lufthansa/DHL. The announcement of a major fleet order in May for seven A330s, one 777 and another 747–400F, all to be delivered before the end of next year, is indicative of the radically changed market conditions in Asia. Along with previously planned additions — three A330s, one A340 and two 747Fs — Cathay will be growing its capacity by over 20% in the next 18 months.

The fleet will total 80 units by the end of 2001, and there are plans to expand to 140 by 2005. This implies an imminent order for 20–30 777s or A340s, for delivery in 2001- 03. In addition, Cathay is one of the key airlines that Airbus has been targeting as a launch customer for the A3XX.

Load factors in recent months have consistently been around 74–75% range which has put Cathay under strong pressure to expand. Even with the additional capacity, Cathay expects to be able to edge up yields at least in the short term.

There is a danger that costs will start to move up again — the new fleet expansion means that the airline will have to employ over 1,400 new cabin and cockpit crew — but Cathay maintains that its unit costs will continue decline, helped by the capacity increase. The target cost level is HK$2.0/ATK compared to HK$2.24 in 1999, and pre–Asian crisis levels of HK$2.64.

In the early 90s Cathay regularly achieved annual traffic growth rates of 10%- plus but the market that it is expanding in now has significantly changed. It is a permanently lower yielding market, with Economy Class and in particular sixth freedom passengers displacing Business and First customers. The Japanese market, which in pre–crisis times accounted for 25% of the airline’s profits, is now characterised by executives travelling in the back of planes while the tourists who abandoned the island–state in the wake of the Chinese hand–over are now just beginning to trickle back.

The move from Kai Tak to Chek Lap Kok has provided Cathay which an airport to rival Changi as Asia’s leading hub. However, the capacity constraints at Kai Tak airport afforded a certain protection to Cathay and shaped Hong Kong’s ASA policy. Now with an unconstrained airport, Hong Kong authorities are eventually going to have to adopt a more liberal approach to ensure the type of overall growth in traffic needed to justify the investment.

In such circumstances rapid expansion is the logical strategy for Cathay to pursue. It has developed a genuine hub system at the new airport with five waves of connecting flights a day. It claims that a 31% increase in meaningful connections between 1999 and 2000 will leapfrog it ahead of SIA as a network carrier.

But one of Cathay’s fundamental problems, as well as being its main opportunity, is its home market. SIA has been able to take advantage of the Asian crisis to build its "domestic" market, first by winning more traffic from beleaguered Garuda and MAS in the Indonesian archipelago and Malaysian peninsula, and then by investing in Air New Zealand and Ansett in order to consolidate its position in the Australasian market. Cathay too has been able to exploit the problems of PAL and gain local and connecting from the Philippines, but Cathay’s attempt to invest in and take over the running of PAL was firmly rebuffed by Lucio Tan.

For Cathay the home market is the PRC, and Cathay thinks of itself as the premier Chinese airline, positioned to be the leading carrier of international air traffic to/from China. But actually exploiting this massive opportunity is as always complicated as a result of the convolutions of Chinese aviation policy. Cathay’s main shareholders are:

- Swire Pacific (with about 44%), the publicly quoted arm of the Swires Group, which has extensive mainland Chinese interests in engineering, brewing, property development, and a history of trading in the country that goes back to 1866.

- CITIC Pacific (with about 25%), the Hong Kong subsidiary of the mainland Chinese investment vehicle, CITIC.

- CNAC (with about 2%), the Hong Kong subsidiary of Beijing–based CAAC, which is the ultimate owner of the mainland Chinese airlines and the regulator of the aviation industry.

In turn, Cathay is linked with Dragonair, the main Hong Kong–mainland China airline. In 1997 Swires and CITIC Pacific each sold 17.7% of Dragonair to CNAC, which is now the major shareholder with 36%. Swire Pacific and Cathay together have about 26% of Dragonair and CITIC Pacific 29%.

This structure was supposed to establish Cathay’s position within the "one country, two systems" framework. The cross–ownership of CITIC and Swires was intended to minimise unnecessary competition between Cathay and Dragonair, with the two airlines in combination offering services to most Chinese cities from Europe and the US over Hong Kong. (Cathay itself cannot serve internal Chinese points directly).

However, according to the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (CAPA), an Australia–based consultancy, Dragonair’s majority owners, CNAC, may have a new role for this airline.

CAPA suspects that Dragonair will soon be competing directly with Cathay on some Southeast Asian routes, exploiting its cost advantage. Already Dragonair has signaled its intentions by announcing a Hong Kong- Dubai–Manchester service in August in direct competition with Cathay. Dragonair fleet plans may also indicate that it has ambitions beyond the Hong–China markets. Six A320s, one A321 and two A330s (plus a further two options) are on order which will double the carrier’s current fleet.

As Dragonair cannot operate pure domestic services (for example, between Beijing and Shanghai), Cathay also needs to strengthen its links with one of the three big domestic carriers — either Shanghai–based China Eastern, Guangzhou–based China Southern or Beijing–based Air China. Talks have recently taken place between Cathay and China Eastern on the possibility of an equity investment. The Chinese authorities are considering raising the stake foreigners can hold in a mainland carrier from 35% to 49%. China Eastern appears to have rejected Cathay’s initial offer but this deal could still be done.

Another complication in the world of Chinese aeropolitics is the possibility of direct flights between Taiwan and the mainland. Currently about 2m passengers a year fly between Taiwan and Hong Kong to connect onto Dragonair or one of the other Chinese airlines on order to get to their final destination in the mainland. Cathay carries roughly half the Taiwan–Hong traffic, China Airlines and EVA the rest. If or when the ban on direct services is lifted the vast majority of these passengers will choose more convenient, shorter direct flights to the benefit of China Airlines and the mainland carriers but to the detriment of Cathay. This development is , however, at least two years away.

| Current fleet | Orders | Remarks | |

| (options) | |||

| 747-200F | 4 | ||

| 747-400F | 2 | 3 | Delivery late 2000, mid 2001 |

| 747-400 | 19 | ||

| 777-200/300 | 11 | 1 | Delivery 2000 |

| A330-300 | 12 | 10 | 7 to be delivered in |

| 2001, 3 to be leased | |||

| immediately | |||

| A340-300 | 14 | 1 | From ILFC |

| Total | 62 | 15 |