Latin American alliances: sleeping with the enemy

June 1999

The past couple of years have seen Latin American airlines scramble to forge alliances with the major US carriers, and the economic problems spreading from Brazil have only accelerated the process. But is “sleeping with the enemy” a wiser strategy than getting together with your regional counterparts? Will Latin America retain a multitude of small operators but be wholly–owned by the US Majors? Or will intra–regional consolidation lead to a market of fewer but stronger independent airlines?

This subject was debated by a panel of eight Central and South American airline CEOs at Aviation Latin America & Caribbean magazine’s annual conference, held in Miami in early May. At this remarkable gathering, the airline bosses explained what they wanted from alliances and spoke of their visions for the future.

In the early 1990s Latin America saw much intra–regional consolidation in response to American’s aggressive expansion. This included the formation of the Taca, Vasp and CINTRA consortia and some acquisitions by LanChile and others. But in recent years virtually all of the commercial and equity alliances have been with the four major US carriers — American, United, Continental and Delta.

This sudden change in emphasis and the pace and scale of the process have created a rather confusing overall picture of the Latin American alliance scene. However, the north–south deals can be broadly categorised depending on whether the Latin partner is strong and successful or whether it is weak and in need of cash and other types of assistance (most, of course, fall somewhere between those two extremes).

Alliances between equals

The best–positioned alliance partners include Varig, LanChile and Taca — all well–established companies with dominant local market positions and good international reputations. Although all are currently performing rather poorly financially (Varig is in the middle of yet another painful cost–cutting programme), they have been able to team up with the US carriers more or less as equals.

Varig and LanChile have also been judged to be good enough to be accepted into their US partners’ global alliances. Varig, the region’s largest carrier with a strong international presence and a high service quality, joined Star immediately after defecting to United from Delta in October 1997.

LanChile, which is financially successful, has an exceptionally strong local and regional market position and is the first and so far the only South American carrier to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange, will become the eighth member of oneworld next year. This was announced in mid–May after the US DoT tentatively granted antitrust immunity for the LanChile/ American alliance (with standard conditions like excluding the Miami–Santiago route and eliminating the exclusivity clause). The decision came after an 18–month wait and will pave the way for the signing of a USChile open skies ASA.

Grupo Taca, which includes El Salvador’s Taca and its large minority stakes in Guatemala’s Aviateca, Honduras’s SAHSA, Nicaragua’s Nica and Costa Rica’s Lacsa, has been developing its code–share alliance with American since securing DoT approval for the deal about a year ago after a two–year wait. The consortium’s success and important position in Central America gave it clout in negotiations with the US carrier.

These alliances do not involve equity stakes; rather, they are operational and marketing relationships governed by long term contracts. However, CEOs like Taca’s Federico Bloch do not discount the possibility of making equity stakes available to US carriers and others in the future, in order to meet investment needs if finance will not be readily available in international debt markets.

In addition, there are a host of looser but potentially promising north–south marketing and code–share relationships, which include particularly the Mexican and Brazilian carriers: Aeromexico’s and Transbrasil’s code–shares with Delta, Mexicana’s with United and Vasp’s with Continental.

Rescue deals involving equity

The alliances that fall into the less desirable second category typically involve equity purchases by the US Majors. The main ones have been Delta’s 35% purchase into AeroPeru, American’s 10% investment in Aerolineas Argentinas and Continental’s 49% acquisition of Panama’s Copa. Those smaller airlines offered desirable local or regional route networks but many were in dire need of capital or management assistance. With the equity purchases, the Majors obtained a say in the day–to–day running of the companies and added security through board seats and voting or veto rights.

However, there have been some mistakes. Delta’s early 1998 investment in AeroPeru was one: the Peruvian carrier was not able to recover from various wounds inflicted by its own government. These included a botched privatisation, an open skies ASA with the US, domestic deregulation, granting cabotage rights to foreign carriers and horrendous fuel taxes. In January 1999 Delta and its investment partner CINTRA decided not to inject more funds and put their stakes up for sale, as a result of which the debt–ridden and cash–starved carrier was forced to cease operations. Although AeroPeru’s debt has been successfully reduced, it faces liquidation if strategic partners cannot be found in the near future.

American’s acquisition of a 10% stake in Interinvest — a holding company that owns 85% of Aerolineas and 90% of Austral — late last year holds much more promise for both parties. The anticipated benefits to the Argentine carrier include help with fleet renewal, unit cost reduction, upgrading systems, improving service quality and better access to the US market. The carrier’s new management, headed by former American executive David Cush, has already sorted out the business plan, recapitalised the company, placed a $1.3bn order for 12 A340s and outsourced all information technology to Sabre — and the focus has now shifted to service quality.

ACES’ earlier plans to sell a 19% equity stake to Continental fell through mainly because of a collapse in the Bogota stock–market. However, the ambitious Colombian carrier does have a code–share with Continental and is continuing to seek a US industry investor. Meanwhile Panama’s Copa has almost completed the sale of a 49% stake to Continental. Copa actually left its marketing partnership with Grupo Taca in favour of an equity alliance with the US Major.

Copa’s CEO Pedro Heilbron says that the carrier wanted access to the US market, cost synergies, attractive world class systems and technical and human resources, that Continental shared a vision of Copa’s growth and future potential and that there were no conflicts of interest. Its ability to offer a successful, strategically important hub through which Continental could channel traffic to Central and South America no doubt gave it a fairly strong negotiating position.

The code–share alliance was formally launched in late May when Copa took delivery of the first of 12 new 737–700s that will replace its fleet over the next few years. The Panamanian carrier also unveiled a new corporate image and a new business class and announced full participation in the OnePass FFP. Codesharing will begin on June 10, initially on 35 Continental flights to 22 US cities and on Copa’s services to Miami, Lima and other Latin American destinations.

Why link up with the US Majors?

The Asian flu, the Russian banking crisis and Brazil’s currency and economic problems have drastically reduced the availability of foreign capital for companies in emerging market economies, while local debt and equity markets are still very poorly developed in Latin America. Only the strongest airlines there have any realistic hope of raising commercial debt capital.

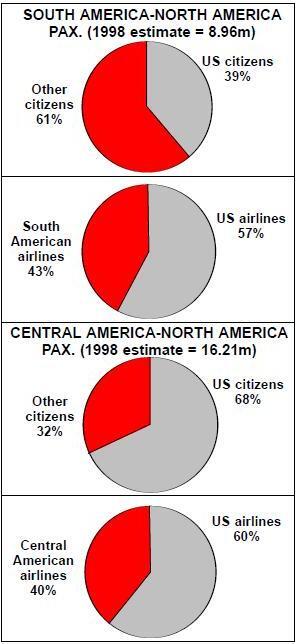

At the same time, several years of record profits have enabled the US Majors to build up healthy cash reserves. They find Latin America extremely desirable as it is currently the fastest–growing airline market in the world. Last year they were able to boost their capacity to the region by 28%, when Europe saw only 9% growth and Asia needed a 5% reduction. Consequently, the US Majors are an obvious source of capital for the weakest Latin American operators.

The added advantage for Latin carriers, of course, is gaining improved access to the US domestic market. For example, Aerolineas is neck–and–neck with United and American in market share on its routes to Miami and New York, but its traffic share beyond those gateways is a pitiful 8%. The airline hopes that the alliance with American will help solve that problem.

In fact, many of the Latin carriers feel that the potential benefits from co–operation are far more important to them than the actual investment. Copa’s CEO Pedro Heilbron says that his company spent a lot more time negotiating the alliance agreement with Continental than the financial aspects of the deal.

Like many airline alliances elsewhere, the US–Latin America deals are designed to offer mainly revenue benefits. This is a pity because the Latin carriers could really benefit from cost savings. But the US Majors do not have to worry about economies of scale, and the Latin carriers do not bring enough to the negotiating table to be able to press the issue.

An exception here are the global alliances like Star, which should be able to offer members like Varig cost savings from the sharing of terminal facilities, joint reservations, joint purchasing, cargo co–operation, wet leasing of idle aircraft and suchlike.

Merrill Lynch analyst Candace Browning suggests that the US–Latin America alliances could help solve the excess capacity problem in those markets in much the same way as the British Airways–Qantas union eliminated excess capacity on UKAustralia routes.

Many Latin American airline executives feel that their carrier cannot afford not to belong to one of the global alliances. They need world class standards in service quality and safety, as well as systems and procedures. Even companies like LanChile believe that they could not survive an open skies regime with the US without a US partner.

How to survive an alliance with a US Major

But there are also dangers in sleeping with the enemy (also see pages 18–19). In other parts of the world, US carriers usually forge alliances when they are unable to introduce own–account service due to bilateral or other restrictions. Not so in Latin America, where liberal or open skies ASAs give them plenty of access, including fifth and sixth freedom rights. What if the US carriers diminish the international roles of the Latin American carriers as, despite the alliances, they continue their own rapid expansion into the region? And given the precarious financial state of many Latin carriers, could the US Majors even tap into the local markets and reap all the benefits themselves?

Merrill’s Browning recommends three strategies for the Latin carriers to follow. First, they should tread very carefully when choosing an alliance partner and deciding which corporate governance concessions to accept. While some concessions could actually prove beneficial, inserting new controls and fresh ideas, others may just aid a stronger competitor and hamstring future growth.

Most importantly, the partner should accept that your local market is yours, and that it is in the alliance’s best interest to promote your growth in the area. The Latin airline CEOs also stressed this point. “I don’t think an alliance will work if participants fall short in their own country”, suggested a senior Varig executive.

Second, now is the time for Latin carriers to do something about overcapacity. Browning suggested that the best way to deal with that problem and achieve a more competitive position generally might be for two local carriers to merge and rationalise their fleets.

Third, Latin carriers should profitably dominate their local markets. “The more your market becomes identified as yours, the less tempted European and US carriers will be to poach in your backyard.”

Browning cited the textbook example of LanChile, which has achieved a 75% market share in Chile and a unique position in the region’s booming cargo market through acquisitions and smart management strategies. “That set of strengths allowed LanChile to maximise its influence in negotiating an advantageous alliance structure with American, avoiding selling an equity stake and suffering any sort of American colonisation.”

Taca’s CEO Federico Bloch also stressed the importance of market dominance: “One brings two things to the party: money or market dominance. I think few airlines in Latin America bring money to the table.”

Regional consolidation?

Airline CEOs like ACES’ Juan Emilio Posada say that they are at present totally focused on developing alliances with the US carriers and do not envisage regional consolidation until the north–south process has been completed. The reasons cited include the need for capital, the strategic benefits of linking up with the US Majors, underdeveloped capital markets and competition and antitrust authorities in many Latin American countries.

However, most in the industry accept that the emphasis will shift to intra–regional consolidation sooner rather than later. And executives like Taca’s Bloch believe that the process will be extensive for three reasons. First, Latin America has high growth potential in virtually every sector of the market. Second, rapid liberalisation will increase competition, forcing the industry to consolidate. Third, Latin carriers are grossly under–capitalised and will have to consolidate in order to capture the funds needed for growth.

Bloch also regards future equity links as the key to helping existing alliances achieve their objectives. The current alliances are essentially based on increasing revenue on existing networks, but managing growth will be much more difficult due to conflicts of interest. As the partners start looking for ways to align economic interests completely, equity links come into play.

Bloch predicts a two–phase consolidation process. First, there will be only minority equity positions because of bilateral, labour and foreign ownership rule constraints. Depending on how fast those obstacles can be abolished, in 5–10 years there could be extensive mergers within the region, to probably just a handful of airlines or airline groups.

As an alternative to mergers, Bloch envisages new types of structures like large holding companies, which will get around some of the labour and other obstacles but will be a handicap in obtaining all the economic benefits. The holding company idea was first proposed by Avman’s Bob Booth, a prominent Latin American airline industry expert. In essence, executives like Bloch are talking about eventually becoming public companies.

In the shorter term, there will probably be more co–operative ventures within the region. However, as yet there is no sign of anything along the lines of the remarkable $2bn joint A319/320 order placed by Taca, LanChile and TAM in early 1998.

LatinPass, the frequent–flyer programme owned by 10 Latin carriers, has survived because it has been able to adapt to the times. The programme now allows its members to have relationships with the four US Majors and has just opened membership to non–owners, including all airlines in Latin America and the Caribbean.

While carriers like Taca may well lead the process of further airline consolidation with mergers with South American operators in the future (at present it is focusing on building feeder links), Mexico may see the merging of Aeromexico and Mexicana. The domestic Mexican market is not big enough for two major carriers, while the country needs a strong representative in global alliances. The planned sale of the government’s and banks’ equity in CINTRA was again postponed late last year, with no firm dates set.

The combination of economic problems and the need to consolidate will undoubtedly mean many Latin American airline failures. Merrill’s Browning suggested that the Latin American market right now is similar to what the US market was like 15 years ago — in transition to an industry structure of fewer but stronger airlines.

| Major US partner | Latin American partners |

|---|---|

| American | Grupo TACA |

| AVIANCA (subject to approval) | |

| LanChile (provisionally approved April 99) | |

| TAM Group | |

| Aerocalifornia | |

| Aerolineas Argentinas (10% equity) | |

| Aeropostal Alas de Venezuela | |

| Continental | COPA (49% equity) |

| ACES | |

| Aserca | |

| Air Aruba | |

| Air ALM | |

| BWIA | |

| Vasp Group (LAB, Ecuatoriana, TAN) | |

| Delta | Aeropostal Alas de Venezuela |

| Aeromexico | |

| Transbrasil | |

| Air Jamaica | |

| LAPA (Letter of Intent - pending government approval) | |

| AeroPeru (35% equity) | |

| United | Varig (member of the Star alliance) |

| Mexicana | |

| Martinair | TAMPA (49% equity stake) |

| Latin American airline | Latin American partners |

|---|---|

| Aerolineas Argentinas | AUSTRAL (100% equity stake) |

| Southern Winds | |

| AeroVIP/Aerolineas Argentinas Express | |

| TAM Group | |

| ASERCA | Air Aruba (70% equity) |

| Air ALM | |

| Aerospostal Alas de Venezuela | Santa Barbara Airlines (undisclosed equity stake) |

| Air Jamaica | Trans Jamaican (100% equity stake) |

| AVIANCA | SAM, Columbia (100% equity stake) |

| BWIA | LIAT (29% equity stake) |

| CINTRA | Aeromexico (majority equity stake) |

| Mexicana (majority equity stake) | |

| AeroPeru (35% equity stake) | |

| Aerolitoral & other domestic airlines | |

| Grupo Taca | Aviateca (49% equity stake) |

| NICA (49% equity stake) | |

| LACSA (10% equity stake) | |

| TACA de Honduras (100% equity stake) | |

| Costena (50% equity stake) | |

| Trans America Peru (minority equity stake) | |

| TAM Group | TAM Mercosur (51% equity stake) |

| TAM Regionais (100% equity stake) | |

| LanChile | LADECO (100% equity stake) |

| Fast Air Cargo (100% equity stake) | |

| LAN Peru (49% equity stake) | |

| ABSA, Brazil (undisclosed equity stake) | |

| Florida West International (24.9% equity stake) | |

| Vasp Group | Lloyd Aero Boliviano (49% equity stake) |

| Ecuatoriana de Aviacion (49% equity stake) | |

| Transportes Aereos Neuquen (49% equity stake) | |

| Varig | RioSul (100% equity stake) |

| PLUNA (51% equity stake) |