British Airways' zero-growth choice

June 1999

British Airways has accomplished the near–impossible. It announced a fall of 55% in net profits for financial year 1998/99 to £206m ($330m) — the lowest for six years — yet it has not been castigated by stock–market analysts. On the contrary, they and other commentators are either praising the originality of its new strategy, or at least are preoccupied with working out what it could mean.

There are two interrelated elements in British Airways’ strategy — a potentially radical route rationalisation and a new concentration on yield enhancement to be achieved through non growth.

The aim apparently is for British Airways to stop operating loss–making domestic services to London. The airline says that it is focusing on eliminating unprofitable market segments, mainly domestic to Europe passengers transferring at London Heathrow. Stage one of the airline’s route–rationalisation process is to examine whether the present connecting services could be converted into direct services from UK regional points to the continent. If British Airways still cannot make the routes work they will either be closed or outsourced to a subsidiary or a franchisee.

Few details about the rationalisation have been provided, and indeed British Airways has refused to identify which routes are under threat. Perhaps the situation would be clearer if a distinction had been made between routes and flights — it may be that what British Airways is planning is the closing or conversion of certain flights within certain routes.

Assessing the impact of closing a route is not simple. Direct variable costs — fuel, en–route charges, landing fees, etc — will disappear upon closure — but flight crew costs and allocated overheads will not. Getting rid of the semi–variable and fixed costs, rather than re–distributing them to other routes, requires more general cost–cutting measures and redundancies, unless the whole airline is growing rapidly (which British Airways is not).(Continued on page 2.)

There is always an element of uncertainty about the repercussions of a route closure on the rest of the airline’s network, although modern management information systems (MISs) usually give a pretty accurate picture of the connecting traffic and revenue that will be lost. However, what cannot be predicted is the effect of a new entrant filling the space vacated by the major airline.

Impact on others

The mere fact that British Airways is developing this route rationalisation strategy poses a number of challenges for both the airline’s competitors and its alliance partners.

While British Airways scarcely breaks even on its European and domestic network, its main European rivals fare even worse in their home markets. For example, Lufthansa loses unrevealed but substantial amounts maintaining its overwhelmingly dominant position in the German domestic market and fighting off competition from the likes of Deutsche BA.

If British Airways proves that it can squeeze out more profits by downsizing its short–haul services then Lufthansa and Air France will be forced to reconsider a basic tenet of their strategies and to focus on the costs of maintaining local short–haul dominance.

British Airways’ moves to concentrate its efforts in the area where it is strongest — the intercontinental routes — also have important implications for its current and potential alliance partners within Europe.

For instance, should Iberia and Finnair now be looking at rationalising their unprofitable long–haul routes? This might involve converting some of the current direct flights into feeder flights to British Airways at London for North Atlantic services or even feeding the BA/Qantas hub at Bangkok for Southeast Asian services.

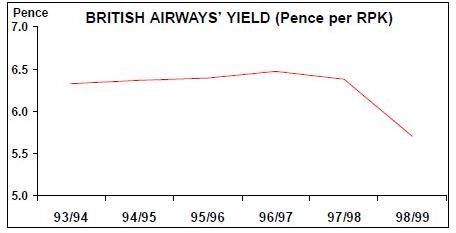

Brilliance of the obvious The other element of BA’s strategy is a laser–like focus on business travellers in order to push up yield, or in the immediate future to reverse the recent decline in yield. What British Airways is doing is startlingly original in the context of the European scheduled airline business — it is saying unashamedly that its strength lies in flying business travellers, that that’s where it can make most money so that’s where it is going to concentrate its resources.

Contrast British Airways’ mission statement with a traditional airline’s goal: for instance, Air France’s strategy of growing at twice the market rate in order to regain market share (see Aviation Strategy, May 1999).

In order to achieve its yield targets British Airways is refitting its business class cabins with luxurious new sleeper seats arranged in semi–circles rather than the traditional rows. British Airways is hoping to emulate the success of its Club brand when it was introduced to the market in the mid–1980s. Following that launch, British Airways’ yield was reported to have leapt by as much as 20%. But competitive conditions in today’s market are very different, with all the major European airlines having developed their own high–quality business classes and — probably even more importantly — having implemented alliance–wide FFPs.

Waving goodbye to the backpackers?

As a corollary to boosting business class capacity and hopefully yields, BA has also stated that it wants to reduce the number of low yielding passengers it is carrying. Again BA’s message is slightly confusing: the aim must be to get rid of empty seats first then the low yielding passengers (assuming that BA’s yield management system is working effectively).

This aim seems eminently achievable as BA switches from 747s to 777s. Moreover, this fleet change is just part of a policy of simply not increasing supply. The 1998/99 preliminary financial report contains a stark statement that runs completely contrary to conventional airline thinking: “Overall mainline capacity will not grow over the next five years.”