Labour woes may hit bigger picture at Northwest

June 1998

Northwest is focusing its efforts on implementing the virtual merger with Continental and expanding the global alliance in Asia. But there is serious trouble on the labour front, which could lead to strikes, inability to code–share in the domestic market or a substantial hike in labour costs. How will the carrier balance the interests of its workforce and the need to secure strategic growth opportunities?

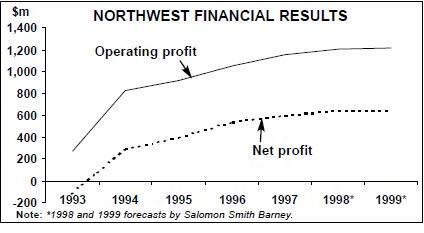

Northwest has come a long way since its near bankruptcy in 1993, when its was burdened with $5bn–plus of debt and could not meet a scheduled debt repayment. A Chapter 11 filing was averted only thanks to a last–minute financial restructuring, which included an $886m three–year package of labour concessions in return for a 25% equity stake for employees, and a subsequent reduction and refinancing of the bulk of its debt.

Since its spectacular turnaround in 1994, Northwest has earned net profits totalling $1.9bn. It is one of the most efficient US carriers, with profit margins that have consistently been among the best in the industry.

For 1997 the company posted an operating profit of $1.2bn and a net profit of $597m, representing 11.3% and 5.8% of revenues. The balance sheet has also strengthened considerably. Long–term debt and capital leases fell from $5.4bn at the end of 1993 to $2.8bn at the end of 1997, while total assets rose from $$7.6bn to $9.3bn. At the end of March, Northwest had an ample $1.1bn in unrestricted cash and short–term investments and total available liquidity of $2.2bn. Northwest should have no difficulty meeting the now evenly spread–out debt repayments and funding strategic investments. On May 1 it repurchased KLM’s remaining holding of 18.2m of its common shares, which was originally due to take place in tranches over a three–year period, for $780m. This was paid with a combination of $337m cash and senior unsecured notes due over three years. At this stage Northwest hopes to complete its $519m proposed purchase of a 15.4% stake in Continental by the end of 1998. It expects to pay $367m in cash and issue 4.2m new common shares. To restore liquidity, in May the company secured an additional $1bn revolving credit facility.

Northwest never had a clearly–defined cost–cutting programme in place, but the 1993 wage concessions were followed by a fairly extensive restructuring of the route system. This and better cost controls enabled unit costs to be lowered.

Last year Northwest’s costs per ASM, at 8.63 cents (excluding freighters), were the lowest among the large majors. This was achieved despite the fact that the wages of Northwest’s workers snapped back to the August 1993 pre–concession levels during the second half of 1996. However, since the company was then able to stop issuing common and preferred stock to employees (a practice that had been recorded as huge non–cash operating cost items), the net impact on the profit and loss account was not that detrimental (salaries and wages rose by $314.5m or 11.6% in 1997, compared with a $242.8m non–cash stock payment in 1996).

The airline was lucky in that its route system had minimal exposure to Continental Lite or the new entrant low–cost operators that wreaked havoc on other major carriers’ yields a few years ago. Service enhancements, better yield management and focus on stronger markets led to steady yield improvements. In recent years Northwest has maintained a domestic unit revenue premium over its main competitors, although its overall yield has deteriorated recently largely because of the Asian crisis.

One major concern is that, over the past two years, Northwest has slipped seriously in the DoT’s service quality and punctuality rankings and earned low marks in customer surveys. It used to be among the highest–rated carriers in terms of service standards. The lapses have been blamed on a multitude of factors, including lack of terminal capacity at the main Detroit hub, the high maintenance requirements of DC–9s, faulty airport equipment, poor scheduling, a shortage of pilots and low staff morale.

The proposed link–up with Continental, which now has the industry’s best service standards and on–time performance, has added new urgency to Northwest’s efforts to rectify the problems — after all, the idea behind the alliance is to offer a seamless service. The carrier is now trying to improve and overhaul everything from facilities and equipment to training programmes.

Impact of the Asian crisis and the new Japan-US ASA

The Asian economic crisis has so far had little visible impact on Northwest’s overall financial results, even though the carrier derives about 30% of its revenues from Pacific operations. Net earnings quadrupled in the fourth quarter of 1997 and rose by 10% in the March 1998 quarter because the weakened demand on the Pacific was offset by exceptionally strong domestic and North Atlantic demand, and lower fuel prices.

Northwest was more prepared for the situation than, for example, United, because it had been experiencing problems on the Pacific for a couple of years due to overcapacity and reduced demand from Japanese tourists (a result of Japan’s lengthy recession and a weaker yen). In any case, the Asian Tigers generate less than 18% of Northwest’s Pacific revenue (i.e. only about 5% of its total revenue). About half of the Pacific sales originate in Japan and 31% are generated in North America, where Asian business travel is holding fairly well in support of US exports. The airline roughly broke even on the Pacific routes last year, following $94.2m and $96.7m operating profits in 1996 and 1995 respectively.

However, the situation worsened in the March quarter, when Pacific passenger revenues fell by 12.6% and the yield plummeted by 10.5%. This was largely blamed on the economic softening in Japan and a further weakening of the yen, which led to a 10% decline in Japanese tourist arrivals in the US.

Northwest now expects an operating loss for the Pacific in 1998, though it is trying to limit the damage with service reductions. Among other things, it has cut capacity between Japan and the beach markets of Guam and Hawaii by 10% and eliminated its three–per–week Detroit–Seoul service.

However, stronger markets elsewhere have absorbed the capacity and, within Asia, China remains a bright spot (an additional weekly Detroit–Beijing flight was added in April).

To make matters worse for Northwest, the new liberal US–Japan bilateral, signed on January 30, has opened up the routes to substantial additional competition. American, Continental and Delta have received 76 new weekly frequencies, while TWA will enter the market with 14 weekly code–share flights with Delta. It is mind–boggling that all this expansion is taking place at a time when the Japanese economy is plunging further into recession, but the airlines have been clamouring for access to those prestigious markets for a long time.

Northwest’s initial response has been to suspend operations on the profitable Chicago–Tokyo route, mainly in response to American’s and United’s new or planned services from their hub. However, the combination of Northwest’s existing dominance and various provisions in the new ASA should ensure that it retains a strong position in the Pacific market.

Northwest was one of only two US carriers (the other one was United) to secure unlimited rights to fly between any US and any Japanese point. It has now launched a new Minneapolis- Osaka service and introduced a second daily flight on the Minneapolis–Tokyo route. It will begin Detroit–Nagoya non stops (linking the world’s two largest car manufacturing centres) and Los Angeles–Tokyo flights in early June.

This will be followed by a seasonal Tokyo- Anchorage service, which aims to attract leisure traffic to Alaska from all around Asia. Northwest’s existing code–share partner Alaska Airlines will offer connections from Anchorage to the West coast, providing opportunities for Asian tourists to visit multiple US cities.

The new ASA also confirmed Northwest’s fifth freedom rights to serve any point in Asia beyond Japan (previously Japan did not always respect those rights). It currently serves nine Asian cities via Tokyo Narita, where it is the second largest carrier (after JAL) with 316 weekly slots. But because of slot constraints at Narita, growth now focuses on Osaka where Northwest is already the largest carrier.

The new ASA ensures that Northwest will retain its existing slots at Narita and Kansai and get its fair share of new slots when second runways are built. Northwest’s important all–cargo services between the US and Japan and beyond will benefit from increased operational flexibility. And, significantly, the bilateral provides opportunities for code–sharing with US and Japanese partners, as well as with other Asian carriers to third countries.

Mature relationship with KLM

The equity relationship between KLM and Northwest was never a happy one, and in 1995 KLM sued Northwest in US courts for breach of agreement after Northwest adopted anti–takeover defences. The two–year legal squabble, which the two always viewed as an independent dispute that should not get in the way of service expansion, was amicably settled in August 1997 when KLM agreed to sell its 19% stake back to Northwest (see KLM Briefing, Aviation Strategy May 1998).

The alliance itself has been a commercial and financial success, generating annual profits of around $50m for Northwest and $150m for KLM. It has enabled the carriers to initiate and expand service on many transatlantic sectors that neither could operate profitably on their own. Atlantic service and traffic doubled between 1993 and 1997.

Joint or code–share services now link 14 US cities with Amsterdam and those gateways with 150- plus beyond–points in the US and 70–plus in Europe, Middle East, Africa and India.

The settlement of the ownership dispute led to the signing of an expanded ten–year global joint venture agreement in September 1997. This called for increased co–operation on the Atlantic and in Canada and Mexico, as well as closer coordination of air freight divisions, computer systems, marketing and other functions. As a result, Northwest has assumed responsibility for KLM’s marketing, sales and operations in North America and Mexico, while KLM is reciprocating on the European side. The two have also introduced new code–share services linking Seattle and Philadelphia with Amsterdam.

Virtual merger with Continental

Northwest’s strategic efforts now focus on developing co–operation with Continental, following the signing of the alliance agreement on January 26. The two propose to connect their networks through extensive code–sharing, FFP links and suchlike, and the deal also envisages cooperation between Continental and KLM.

The idea behind this "virtual merger" and the similar alliances subsequently forged by American and US Airways and Delta and United is to get many of the benefits of mergers without the hassles. But the Northwest deal differs from the others in that it involves an equity link and therefore is subject to formal antitrust review by the Justice Department.

Northwest’s acquisition of Air Partners’ 15.4% stake will represent 50.4% of Continental’s fully diluted voting stock. But the shares will be placed in a trust and Northwest has agreed not to use its voting rights except in certain limited circumstances. The absence of control is important to avoid a transfer of international route rights.

Northwest and Continental are now in the process of linking up their FFPs. The rest of the deal will face tough regulatory scrutiny (also by the DoT), which could be a lengthy process. On the one hand, there’s very little route overlap (only seven nonstop routes). On the other hand, there are serious concerns in Washington about growing industry concentration, hub domination and predatory behaviour by the majors.

The carriers also need to secure the approval of their pilots’ unions, whose contracts give them veto power over domestic code–sharing. The situation is particularly serious at Northwest, where the pilots have tied the approval of code–sharing to the successful conclusion of new contract negotiations that have dragged on for more than 18 months.

The alliance offers few cost savings since separate managements, employees and fleets will be retained and there will be no workforce reductions or hub closures. Economic benefits will arise mainly from increased revenue through new city pairs and connection opportunities. However, the benefits will probably fall well short of the initially estimated $500m aggregate annual pre–tax income now that the main competitors are forming their own alliances.

Northwest will benefit from access to Continental’s markets in the South and the Northeast — particularly the Houston and Newark hubs, where Continental still has good growth opportunities. By contrast, Northwest has already maximised the use of its Detroit and Minneapolis/St. Paul hubs.

The deal will give Northwest access to Latin America, where it is non–existent and where Continental has grown extensively in recent years. The ability to code–share in Asian markets will also be useful as competition intensifies and Asian economic woes continue. The DoT has authorised the two to code–share on services linking Detroit, San Francisco and Los Angeles with Tokyo and Osaka.

The alliance with Continental should also further cement Northwest’s relationship with KLM, which recently secured Alitalia as its south Europe partner and will now gain additional access to the southern part of the US and Latin America.

Search for Asian partners

In a rather nice move to cement the new domestic link–ups and fill the Asia gap in the global alliance, in mid–May Northwest and its three US partners (Continental, America West and Alaska) simultaneously signed code–share and marketing agreements with Air China. The five–airline combine will account for 65.6% of the US–China nonstop market and thus be much larger than the alliances recently signed by American with China Eastern and Delta with China Southern.

The deal will involve multiple gateways on both US coasts and all around China, plus Northwest’s Tokyo and Osaka hubs. Northwest and Air China will code–share on US–China and domestic sectors and will also connect in Japan. Continental will gain access to China and its main role will be to feed traffic through Newark and provide Air China access to Latin America. Alaska is expected to boost its service via Seattle, while America West will focus on the West coast to Las Vegas sectors. This will secure Northwest’s presence in a major future growth market, while existing code–share partner JAS will help the carrier penetrate Japan and the rest of Northeast Asia. However, Southeast Asia remains a major gap to be filled. Northwest’s leadership recently indicated that talks have been held with various Southeast Asian carriers, that an equity stake would be considered if necessary, and that multiple–airline signings (with the US partners at least) are possible.

Unstable labour situation

But Northwest’s biggest immediate challenge is to secure new agreements with its unions. Contracts with the main labour groups have been open since the autumn of 1996 and talks have not made progress on economic and job security issues despite the involvement of federal mediators in the ALPA and IAM negotiations.

The unions are pressing for sizeable pay increases (after all, their pay is still at 1992 levels) and are becoming increasingly agitated about the management’s requests for work–rule changes and other "unacceptable" conditions. In April the pilots were reportedly also asked to agree to the setting up of a low–cost division, dubbed N2, which would involve 10% pay reductions for up to 40% of the pilots who currently fly narrowbody aircraft — something that the union refused to consider.

An intensive ten–day round of talks with ALPA ended in mid–May without any progress and a strike remains a possibility (if the federal mediator declares an impasse and after a 30–day cooling–off period expires). Over the past month the pilots have been conducting informational picketing at key airports, while work slowdowns by machinists have led to some flight delays and cancellations.

Northwest is the only one of the US majors still facing problems of this magnitude with its unions — and both ALPA and IAM have board seats. The situation does not bode well for pilot approval of the domestic code–sharing part of the Continental alliance, though many of the benefits would probably be realised without domestic code–sharing. The labour strife is certainly making it harder for Northwest to bring its service quality up to its partner’s standards, and its competitive position is clearly at risk.

| Current fleet | Orders options | Delivery/retirement schedule | ||

| 727-200 | 40 | 0 | To be replaced by A320s | |

| 747-100 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 747-200B | 22 | 0 | To be replaced by 747-400s | |

| 747-200F | 8 | 0 | ||

| 747-400 | 10 | 4 | ||

| 757-200 | 48 | 25 | ||

| MD-82 | 8 | 0 | To be replaced by A319s | |

| DC-10-30 | 15 | 0 | ||

| DC-10-40 | 21 | 0 | ||

| DC-9-10 | 19 | 0 | ||

| DC-9-30 | 113 | 0 | ||

| DC-9-41 | 12 | 0 | ||

| DC-9-51 | 35 | 0 | ||

| A319 | 0 | 50 | (100) | 10 per year 1998-2002 |

| A320-200 | 52 | 18 | ||

| A330-300 | 0 | 16 | 8 in 2003, 8 in 2004 | |

| TOTAL | 406 | 113 | (100) |