Will expansion spoil the Ryanair success story?

June 1998

Ryanair is Europe’s original low fare, low cost point–point scheduled airline. And, unlike most of the low–cost competitors that have followed, Ryanair is profitable. But can and will the airline keep to its successful strategy now that it is embarking on an ambitious expansion plan, with capacity increasing by 25% a year?

Ryanair’s profitability derives from the adoption of a Southwest–type strategy in Europe. Although Ryanair was founded in 1985, the airline was loss–making until the current low–cost, no–frills strategy was introduced in 1991. At that time routes were cut from 23 to four, turboprops were replaced by jets, and routes were launched from London Stansted.

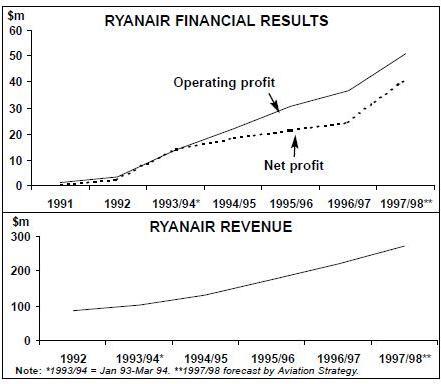

The effects were immediate, and today Dublin–based Ryanair is, for its size, one of Europe’s most profitable airlines. In the 1997/98 financial year ending March 31, net profit is forecast by Aviation Strategy to top $41m (15.3% of revenue) — see chart, right. Until recently Ryanair had maintained a very low profile, seemingly happy to let the customers roll in and profits rack up. But the low–key approach changed in 1997 when Ryanair expanded outside UK and Ireland for the first time. Six 737–200s were added in 1997 to serve three new routes — Dublin to Paris (Beauvais) and Brussels (Charleroi) and London Stansted to Stockholm.

This, however, was just the start of a much larger expansion plan. A London–Oslo route was followed by six new routes out of Stansted starting in May/June 1998, to Venice, Malmo (Kristianstad), Pisa, Rimini, Lyon (St. Etienne) and Toulouse (Carcassonne). This brings the total Ryanair network to 26 destinations in seven countries, centred on Dublin (14 routes) and Stansted (13 routes). In 1998 Ryanair forecasts it will carry 5m passengers.

But Ryanair’s ambition does not stop there. In March 1998 the airline announced a firm order for 25 737–800s, with options for another 20. They will be delivered at a rate of five per year from March 1999 onwards, with the earliest optioned aircraft being available in 2001.

Some will replace 737–200s in order to increase capacity (but not frequency) on routes such as Dublin–Birmingham (allowing the -200s to switch to new routes), others will go to increase frequency (e.g. on Dublin- Cardiff) and others will go to new routes. According to Tim Jeans, Ryanair’s commercial director, at least five new routes will start each year. In total, Ryanair’s capacity will expand by 25% per year.

It is this massive order of 737s and its possible effects that begs the question: will capacity expansion — and the imperative to push the aircraft onto existing or new routes — tempt Ryanair to tinker with its successful strategy?

Low-cost bedrock The key to Ryanair’s strategy is a low cost base. Four items — aircraft equipment, employees, distribution and airport access, account for well over half of the airline’s costs (see table, page 13).

Prior to the arrival of the 737–800s, Ryanair’s fleet is composed solely of cheap, second–hand 737–200s. The 737–800s will be cheaper to operate on an operating cost/ seat basis (fuel cost per seat will be 38% cheaper, for example) — but that does not include the cost of funding their purchase.

The firm orders cost approximately $1.1bn at list prices, but Ryanair is likely to have negotiated a discount on this of at least 20%. The aircraft will be financed via cash flow, commercial borrowings and equity (see page 13). Matthew Stainer from Morgan Stanley Dean Witter in London calculates that while the deliveries will cost $175m per year (i.e. five aircraft at an estimated $35m each), the airline will generate an average of $114m in cash per year over the next four years. Given that Ryanair’s cash reserves are relatively high ($89m at December 31, 1997), and long–term debt is low ($2.6m), the airline should have no problem in attracting all the equity/debt funding it needs.

But there will be secondary effects, and the most important of these may be on personnel. Employees are a key component of Ryanair’s low costs. Pay is linked to productivity incentives, which account for approximately two–thirds of an average flight attendant’s pay and one–third of an average pilot’s pay. (Ryanair has already planned for the loss of duty–free revenue by exploiting other in–flight revenue, such as telephone cards and rail tickets.)

Yet in the last quarter of 1997, excluding non–recurring bonuses, staff costs rose by 50% compared with the same quarter in 1996, reflecting an increase in staff to 956 from 679 as well as pay increases that were "ahead of the level set by national wage agreements", according to Ryanair.

Ryanair does not negotiate with unions, and until recently employee relations have been good. However, there are signs that this is changing. In January 1998 a dispute with baggage handlers over union recognition lead to work stoppages — a “painful lesson”, according to Jeans.

Although the episode has now been settled, with Ryanair agreeing to take part in a government enquiry into the dispute, the direct cost to the airline was a one–off payment of IR£500 ($730) made as a “thank you” to employees who continued to work normally. The dispute will knock up to $1m off net profits in 1997/98.

This raises the question of whether the payment is truly a one–off. If it is, there is little to stop staff from pressing union recognition claims year after year. The indirect cost of the dispute in terms of labour relations may be even more costly. Ryanair is finding out that while it takes a long time to build strong employer–employee ties, it often takes a much shorter period to undo them.

The bonds that were built up in a small Irish family firm may not survive the discipline necessary for it to expand into a major European airline.

As more pilots, flight attendants and ground crew are taken on to serve the new 737–800s, personnel costs will keep rising, but expansion may also prompt a further drive by staff to get management to recognise unions.

Elsewhere, there is better news for Ryanair’s low cost base — in distribution. The majority of sales are carried out by third–parties on multi–year contracts with fixed commission levels. Last year Ryanair cut the standard travel agent commission in Ireland and the UK from 9% to 7.5%, and despite a threatened boycott by some Irish travel agents, the reduction has been pushed through. However, Lunn Poly and Thomas Cook are still resisting in the UK.

But Ryanair is not stopping there. In 1996 the company set up Ryanair Direct, a reservations and data processing centre in Dublin. The centre has not only pushed up the proportion of tickets Ryanair sells direct to more than 30%, but under Irish taxation law this subsidiary attracts a corporate tax rate of just 10%. This has had the effect of reducing Ryanair’s overall tax rate from 33% to 25% in the last quarter of 1997.

For the immediate future there will still be a role for distribution via agents, says Jeans, particularly if they add value. But Ryanair is now also looking at Internet distribution. The airlines will launch a web site this summer, and it is also examining several possible Internet distribution systems.

As for airport charges, so far there are no indications that secondary airports are starting to claw back any significant margin from Ryanair. Indeed Ryanair often wins key first–mover advantages by securing access to secondary airports at cheap rates.

Sometimes Ryanair secures access to airports for free, or gets the airport operator to subsidise the airline. However, operators of an airport ‘discovered’ by Ryanair often tend to demand higher fees from each succeeding airline that wants to launch services.

Simple and effective route structure

Ryanair concentrates on short–haul, point–to–point services that link popular destinations via secondary airports. There are therefore no through–service costs, and connecting traffic is minimal. But as capacity comes on stream, will Ryanair keep to this formula? The number of routes where a cosy duopoly could be shaken up by Ryanair’s low fares is considerable (particularly as Ryanair’s fares are up to 80% cheaper than the established airlines' fares) — but the number of these that can be served via secondary airports is limited. Already Ryanair appears to be stretching the concept of serving airports close to population centres. St. Etienne is 55km from Lyon and Carcassonne is 90km from Toulouse.

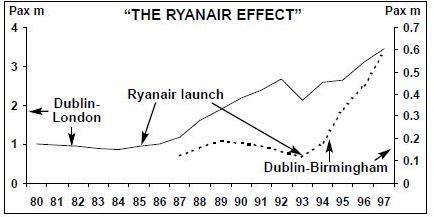

Ryanair argues that it can find suitable routes to put the 737–800s on, and that in any case once the airline enters a route its fares and service concept will engender the so–called 'Ryanair effect' — the phenomenon where passenger traffic booms once Ryanair enters a particular route (see chart, below). This effect may be overstated, however; increasing demand on Ryanair routes out of Dublin was partly a factor of the buoyant Irish economy in the early 1990s and an inbound tourism boom from the UK.

Of course Ryanair’s low fares policy was also a factor, as low fares attracted leisure passengers who until then did not fly (preferring coach, car or train), or did not travel at all.

Ryanair selects routes based on two main criteria, says Jeans. The first is location — each end must be close to major markets — and the second is a low cost operating environment. So, providing that they are close to major population centres, secondary airports will remain at the heart of Ryanair route expansion. "Another reason we have not been drawn to primary airports is because leisure travellers flying with bargain fares are relatively time insensitive," says Jeans. "And that is why we will stick to the knitting." On the other hand, Jeans adds, Ryanair does not want to over–analyse routes. The airline has started many routes that no–one thought viable (e.g. Dublin–Bournemouth), but so far Ryanair has an unbroken record of success.

This begs the question just how the airline will react when an inevitable route failure does come? Will the airline accept the situation as a one–off and keep to its strategy, or would a series of failures entice the airline into trying something different — flying from primary airports for example?

A busy future

Assuming Ryanair keeps to its stated strategy, the role of Stansted will become more pronounced. Jeans says: "Stansted is a node for us — not a hub. But by sheer weight of city pairings, people will start to connect through Stansted. There is big demand for connections at some of the spokes already, but at present development of the hub–and–spoke concept is not part of our strategy — although it is not ruled out for the future". Much more likely in the medium–term is the development of another node, so that Ryanair can then begin to "triangulate the network", says Jeans. But this sounds like the beginning of a hub structure by another name. Ryanair had been 100% controlled by its founders, the Ryan family, until June 1996, when Irish Air (controlled by David Bondermann) and Michael O’Leary (the chief executive) bought a 19.9% stake and 17.9% stake respectively. The Ryan family stake was further diluted in 1997 when Ryanair was floated in Dublin and New York (NASDAQ) at a value of $500m. In Ireland an issue of shares equivalent to 34% of the total was 20 times over–subscribed.

Although the airline is now part of Ryanair Holdings, the Ryan family owns 35.5%, Irish Air 14.6% and O’Leary 14.1%.

Ryanair now plans to list in London (perhaps as soon as this year), at the same raising around £50m sterling. According to Jeans, this will "broaden the shareholder base, and help pay for the new aircraft".

Inevitably, this will bring further scrutiny of the airline — but Jeans says management is aware of this and will accept it — and scrutiny is "good publicity" anyway.

But even if Ryanair sticks to the knitting, the main factor the airline seems not to have factored into its calculation is competition. If successful, Go is likely to be the first of many low–cost subsidiaries launched by Europe’s major airlines. For example, Virgin Atlantic is reported to be contemplating a low–cost airline at Stansted, possibly combining Virgin Express with an acquired airline. In any case Virgin Express is looking at Stansted as another possible hub.

Yet Ryanair seems somewhat relaxed about the prospect of similar low–cost, no–frills competitors. "Price is our key strength because we believe we have the lowest cost base around", says Jeans. "And, faced with competition, we will do what we have to". This is a direct warning to Go at Stansted, yet while BA’s subsidiary will (for now) avoid any direct challenge to Ryanair, if any fare war did occur then surely Go would have more resources than Ryanair.

On the other had, it is easy to be too critical of an airline that — unlike many of its rivals — is making a steady stream of profits. It may even even be under–exploiting one of its key assets — its brand. Outside Ireland and the UK, the Ryanair brand is little known among the flying public and brand promotion is dismissed by the airline as not being applicable to the low–fare leisure market. That is a risky assumption, and as more and more low–cost competitors arrive in Europe it may be foolish to rely on price alone as the key to demand.

But the main danger for Ryanair remains that management becomes impatient with its steady expansion plans and is tempted to try primary airports as an experiment. This would entail higher costs and be the first step towards dismantling a successful strategy.

According to Jeans this will not happen — expansion will be at Ryanair’s own pace, the airline will not depart from its successful formula, and management is determined not to become complacent. Observers will be watching closely to see if Ryanair does indeed keep these promises.

| Current fleet | Orders (options) | Delivery/retirement schedule | |

| 737-200 | 20 | 0 | |

| 737-800 | 0 | 25(20) | 5 in 1999, 5 in 2000, 5 in 2001, 5 in 2002 and 5 in 2003 |

| TOTAL | 20 | 25(20) |

| Revenues | 95/96 | 95/96 | 96/97 | 96/97 |

| $m | % | $m | % | |

| Scheduled | 146.2 | 82.8 | 193.0 | 88.2 |

| Non-flight scheduled | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.1 |

| Charter | 15.2 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 3.5 |

| Cargo | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| In-flight sales | 10.2 | 5.8 | 11.6 | 5.3 |

| Car hire | 2.6 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 1.7 |

| Costs | 176.6 | 100.0 | 218.7 | 100.0 |

| Employees | 34.1 | 19.3 | 40.3 | 18.4 |

| Airport charges | 21.0 | 11.9 | 25.2 | 11.5 |

| Maintenance | 18.4 | 10.4 | 18.6 | 8.5 |

| Fuel | 16.8 | 9.5 | 22.1 | 10.1 |

| Marketing/distribution16.4 | 9.3 | 22.8 | 10.4 | |

| Route charges | 10.2 | 5.8 | 12.5 | 5.7 |

| Depreciation | 8.5 | 4.8 | 10.7 | 4.9 |

| Aircraft rentals | 3.5 | 2.0 | 9.8 | 4.5 |

| Other costs | 17.0 | 9.6 | 18.8 | 8.6 |

| 145.9 | 82.6 | 180.8 | 82.6 | |