Politics drive German airport privatisation

June 1998

Airport privatisation is on the agenda of several governments in 1998 (see Aviation Strategy, December 1997). With a decision due soon on the shortlist for privatisation of Berlin’s airports, Aviation Strategy takes a close look at the privatisation drive in Germany.

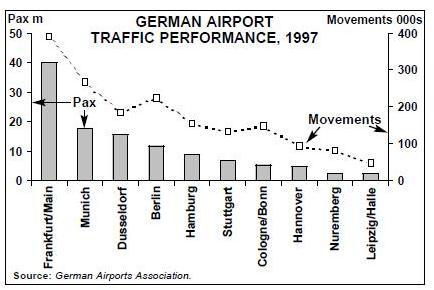

The rationale for the federal government’s decision is clear. The prospect of a doubling of air passengers to more than 200m by 2010, and a resultant need for investment exceeding DM20bn ($11bn), is putting considerable physical and financial strain on Germany’s airports. Although this figure is estimated, it includes DM7bn ($4bn) already programmed and in part invested to meet demand by the turn of the century.

As things stand at present, it is the federal, local and city governments — effectively the taxpayers — that have to dig deep into their pockets. With an increasing number of other, more pressing priorities, it is no longer possible to finance the capital requirements necessary to meet the projected demand for air travel.

The writing has been on the wall for some time, in fact since the fall of the Berlin wall when Germany embarked on the long and hugely expensive process of re–unification, and it is the Berlin airport system which is at the heart of a new direction in airport ownership. Since the federal cabinet’s decision on 28 November 1995 to initiate a total withdrawal from financial participation in airports, privatisation has become a hot topic in Germany, fuelled by the prospect of a new unified airport for Germany’s new capital. But more than that, cutting off the public money supply, said Bundesminister for Transport Matthias Wissmann, is the essential prerequisite for airports to have the freedom and flexibility of making the decisions necessary to strengthen their position in the competitive marketplace.

Yet, in spite of the cabinet’s decision, a reluctance to relinquish control still underlies public statements. It is clear that the federal government is keen to hang on to Germany’s prized gateways of Frankfurt and Munich, at least as long as it can, saying that, because of their strategic importance as vital industrial and economic centres, they should not be allowed to go–it–alone. To underpin this policy the federal government has chosen Hamburg and Cologne, two of the five airports it still has minority stakes in, to serve as guinea pigs for privatisation. But local and city governments have stolen a march on the transport ministry in Bonn, and it was in fact Düsseldorf, owned in equal shares by the State of North Rhine–Westphalia and the City of Düsseldorf, which has become the front runner in the privatisation stakes.

The fact that it was the tragic fire in April 1996 that forced the owners of Düsseldorf Airport to go to the market early only reflects the realisation that large cash payments, either unforeseen or planned, can no longer be easily sold to the taxpayer. The resultant major reconstruction programme, together with its Airport 2000 expansion plan to increase capacity from the present 15m to 22m passengers, requires an investment of DM2bn ($1.1bn). The State of North Rhine- Westphalia, therefore, put its 50% share up for sale and in October 1997 selected Harpen, a German real estate company, with Airport Group International (AGI) as the preferred bidder for the airport. Subsequently, however, the state, trying to squeeze more money out of the AGI/Harpen bid, re–opened negotiations with Hochtief, which it eventually won, paying DM370m ($209m) for the half share, including some DM40m ($23m) to the city for the lease of the airport land. Because the share sale was tied to the lease of the land, parallel negotiations by Harpen/AGI with the City of Düsseldorf for its 50% stake came to nothing. But the big prize is Berlin, and in spite of doubts that traffic levels may not generate an adequate return on investment, seven international consortia have beaten a path to the door of the debt–ridden Berlin Brandenburg Flughafen Holding (BBF). This has been whittled down to two and either one or both will be selected on 2 June 1998 to make a final bid. The winning consortium is expected to be announced in October, which would give Berlin the distinction of becoming the first fully–privatised airport in Germany.

Investment bank BZW is handling the privatisation. The new owner will get a 50–year concession, for which he is expected to invest a sum of DM8bn ($4.5bn) by 2007 to provide the new airport — a development of the former East Berlin Schönefeld facility — with a capacity for 20m passengers.

The concession will also include taking over BBF’s debts, thought to be around DM885m ($499m) and, in parallel, run the existing three airports of Schönefeld, Tegel and Tempelhof until their closure.

The usual suspects

There were no surprises among the interested parties, and they include most major airport companies that have successfully ventured into management abroad, among them the UK’s BAA, Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, Aéroports de Paris (ADP), Aer Rianta of Ireland, and Vienna Airport.

US company (AGI), which headed a consortium also including regional state bank WestLB, Berlin utility company Bewag and Parsons Engineering of the US, withdrew its bid in January. Following hard on the heels of the Düsseldorf fiasco, this would suggest that AGI is either disenchanted with German political machinations, or has changed its mind about the prospects offered in the German market. This may also be the reason for the recent withdrawal of the bid by the Copenhagen Airport/Commerzbank/Bechtel consortium, leaving just two.

These are still formidable, none more so than the Partner für Berlin und Brandenburg heavyweight grouping of Hochtief, Flughafen Frankfurt Main, ABB and Siemens, which must be considered favourite. But the IVG/Vienna Airport/ Dorsch/Dresdner Bank bid may have something to say about that. Winning, however, could turn out to be a mixed blessing if the high expectations for Berlin prove to have been overplayed.

Crédit Suisse/First Boston has proposed a sell–off strategy for Hamburg–Fuhlsbüttel Airport in a report issued to the owners at the end of March 1998, but it is unlikely that the city’s economic ministry will comment before the summer.

On offer is a 50% stake, which includes the 26% federal holding, the 10% stake of the State of Schleswig–Holstein, and up to 14% of the city’s holding. Present plans to implement the sell–off by the end of the year are regarded as over–optimistic. Interest has been expressed by Hochtief, BAA, Vienna, Copenhagen and Frankfurt.

Interestingly, Cologne/Bonn is less enthusiastic about following the government line. The cities of Cologne and Bonn want to increase their combined stake from the present 37.18% to at least a majority 51% holding, citing the importance of the airport as the key to the economic development of the city and the region, as well as a job creator. The city councils argue that this aim is at odds with those of a private investor, whose main priority is earning money. The additional shares would come from both the federal government and the State of North Rhine–Westphalia, with the latter believed willing to sell this year.

Notwithstanding the federal government’s intention of holding on to Munich, the city is in discussions with the Free State of Bavaria about the sale of its 23% holding in Germany’s second biggest airport. Favourite is a listing on the stock exchange which, if agreement can be reached, could take place this year. But Munich will insist that any part privatisation ensures that the airport is developed to its full potential and that the privatisation motives match, to a large extent, the interests of the airport as an economic engine.

Hannover is in the midst of a DM269m ($152m) expansion programme to be completed in time for Expo 2000. The airport’s joint owners, the City of Hannover and the State of Lower Saxony, have contracted UBS in Frankfurt to advise on a partial privatisation, expected to take place after the Expo. Only a minor holding, amounting to 15% from each owner, will be made available in the form of an initial public offer.

This leaves Frankfurt, but the whole privatisation process could be turned upside down if, as is expected, another government takes office in the summer.