US airlines respond to record fuel by cutting deeper

Jul/Aug 2008

In the past month or so, US airlines have made an impressive collective effort to adjust to the tough new fuel environment.

They have announced sharp domestic capacity and fleet reductions, effective in the autumn, and are even pulling back in some international markets. They are aggressively tapping ancillary revenue sources and are looking to step up liquidity–raising efforts.

Will these measures help avert the financial crisis looming in 2009?

The pace of capacity cuts by US airlines accelerated in late May and early June, when the two largest carriers were ready to show the way. American and United announced that they would slash their fourth–quarter 2008 mainline domestic capacity by 11–12% and 14%, respectively, after previously planning only low–single digit reductions. The other large network carriers — Continental, Delta, Northwest and US Airways — then quickly followed suit with their own significant capacity pull–downs.

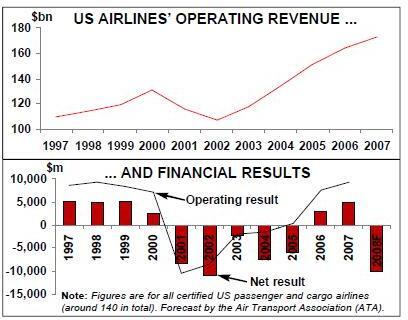

The airlines' moves were, of course, a response to the run–up in the price of oil from the $100–per–barrel level to $130 during April and May, followed by a climb to $140 by mid- June. Oil prices have roughly doubled from the $70 level seen last summer. The Air Transport Association (ATA) estimated in mid–June (based on $140 oil) that US airlines will spend nearly $61.2bn on fuel in 2008, $20bn more than in 2007. A large carrier like United currently expects to spend $3.5bn more on fuel this year.

Fuel now represents almost 40% of the airline industry’s operating costs. US Airways estimated in mid–June that it was spending an average of $299 in fuel costs alone to carry one mainline passenger on a round trip, up from $151 in 2007 and $70 in 2000.

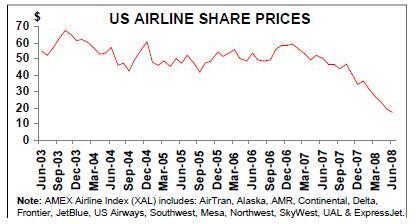

ATA predicted in mid–June that US airlines would lose $10bn in 2008, which would make this year the second–worst in industry history, almost matching 2002’s $11bn aggregate net loss. In a recent testimony to a Senate committee, ATA chief James May talked about the US airlines being "on the brink of financial disaster".

The crisis is worsening, with the continued escalation of oil prices: $142 as of June 27th, with a climb to the $180-$200 level by 2009 now considered a realistic scenario. Consequently, further significant capacity cuts and other remedial action are on the cards, particularly for 2009.

On the positive side, US legacies have entered this downturn better prepared than ever before. They carry significant amounts of cash and have extremely modest aircraft capex plans. New aircraft due for delivery this year were mostly financed last year when the US capital markets were still fully open for airlines.

The capacity cuts focus primarily on the domestic market, but weak international routes have been among the first to go (because longer routes burn more fuel) and several airlines have postponed the launch of new routes to China.

The fleet and capacity cuts serve two purposes. First, they reduce costs and cash burn. Many US airlines still have large numbers of older, less fuel–efficient narrowbody aircraft types in their fleets that simply must go at these oil prices. And even with fuel–efficient aircraft, many domestic and some international routes are no longer profitable at $140 oil. Second, the airlines hope that the capacity cuts will create a better domestic pricing environment.

The domestic capacity cuts focus on September or October, because that is when airlines believe demand will weaken in response to the softening economy and rising ticket prices. Bookings for July–August are strong and the revenue environment remains reasonably healthy this summer.

The capacity and fleet reductions will mean many job losses, though the airlines are trying to minimise the impact on their long–suffering workers by introducing voluntary retirement and "early–out" programmes.

According to one estimate, US airlines cut nearly 22,000 jobs in January–May, and the total could exceed 60,000 in 2008, making this the second worst year for job losses since 2001, when there were more than 100,000 cuts.

Deep capacity and fleet cuts

AMR’s plan, announced on May 21st, calls for an 11–12% cut in mainline domestic capacity and a 10–11% reduction in regional flying in the fourth quarter. The group will be retiring at least 75 aircraft, including 40–45 from mainline operations (mostly MD–80s and some A300s) and 35–40 RJs (probably Embraer 135s). Regional unit American Eagle will retire its entire Saab fleet by year–end. Job losses are likely to be in the thousands. More cuts could be on the way for 2009 through a possible acceleration of MD–80 and A300 retirements. However, American still expects to take delivery of 70 737–800s in 2009–2010. AMR executives have made the point that, even with the higher capex, acceleration of fleet renewal makes sense from a cash flow perspective at the current fuel prices.

On June 4th, a week after terminating its merger talks with US Airways, UAL outlined plans for even steeper capacity and fleet reductions. The airline is trimming its mainline domestic capacity by 14% in the fourth quarter (over 4Q07) and by 17% in 2009 (over 2007). United is retiring 100 mainline aircraft (22% of its fleet), including all of its 94 737s (provided terms can be worked out with lessors) and six of its 30 747s. Of the 100 retirements, 80 will go this year and the remaining 20 in 2009.

United expects to reduce its salaried and management employees by 1,400–1,600 by year–end. There will be significant front–line employee furloughs; so far, United has decided to lay off 950 pilots (nearly 15% of its total), though the airline hopes to minimise involuntary furloughs.

Interestingly, UAL is finally eliminating Ted — the last remaining airline–within–an–airline in the US, though it was only created in February 2004 while UAL was in Chapter 11. The Denver–based unit was nothing more than a separate leisure–oriented brand; it never got its unit costs much below United’s. Its fleet of 56 A320s will be reconfigured to include United first class seats, starting next spring. Continental followed AMR’s and UAL’s example on June 5th, significantly adding to cuts it had outlined in April. Mainline domestic capacity will now decline by 11% in the fourth quarter and by 3–5% in 2009. The airline is accelerating the retirement of its 737- 300s and 737–500s; some 67 of those, including all 737–300s, will have gone by the end of 2009. The aircraft will be sold or returned as leases expire.

The airline will continue to take delivery of next–generation 737s. It has an impressive order book that includes 32 737- 800/900s scheduled for delivery this year and 18 737–800/900s and two 777s in 2009, plus another 100 aircraft on firm order and 100 on option for post–2009 delivery.

However, with the 737–300/500 retirements now vastly exceeding 737–800/900 deliveries in the next 18 months, Continental’s mainline fleet will shrink from the current 375 (as of June 30th) to 344 at the end of 2009.

Continental expects to eliminate 3,000 positions, or 6.7% of its workforce, including management, though most of them are likely to be voluntary. The furloughs will be announced in August, after the voluntary numbers are known. As a gesture, and in line with the company’s tradition of cultivating good labour relations, chairman/CEO Larry Kellner and president Jeff Smisek have declined their salaries for the remainder of this year and any bonus payments for 2008. Delta and Northwest, which hope to complete their merger by year–end, both announced further significant capacity and fleet reductions in mid–June. Including three previous rounds of modest cuts, Delta’s consolidated domestic capacity will now fall by 13% in the second half of 2008. The airline is removing the equivalent of 15–20 mainline aircraft and 60–70 50–seat RJs from its fleet by year–end. The mainline retirements include MD–80s, 757 domestics and 767–300/300ERs. In addition, four domestic 767–400s will be converted for international operations.

In March Delta was the first US airline to offer its workers voluntary retirement and "early–out" packages. Twice as many people(4,000) applied for buyouts than the original goal. Delta has accepted them all, meaning that it can achieve greater cost cuts and efficiencies, in addition to avoiding involuntary furloughs.

Northwest expects its system mainline capacity to decline by 8.5–9.5% in the fourth quarter. The airline is removing a combination of 14 757s and Airbus narrowbodies, reducing its DC–9 fleet from 94 to 61 this year and accelerating the retirement of three freighters. Northwest has not finalised employee cuts but is likely to look to voluntary early–outs.

But the Delta/Northwest combination, if it materialises, should be well placed for international growth because of both parties' prudent investments in long haul aircraft. Delta is the launch customer for the 777LR, while Northwest is the US launch customer for the 787 (with 18 firm orders and 50 options, and the first delivery now in November 2009).

US Airways, which is somewhat of a legacy/LCC hybrid, is currently looking to trim its mainline domestic capacity by 6–8% in the fourth quarter and by 7–9% in 2009. The carrier also announced on June 12th that there would be 1,700 job reductions (5% of the workforce), starting with front–line staff attrition this summer and as many voluntary cuts as possible in the autumn.

On the fleet front, US Airways is returning to lessors 10 aircraft (six 737–300s this year and four A320s in first–half 2009) and cancelling leases on two A330–200s that it was due to receive next year. The airline has contractual impediments in its pilot deal that prevent it from downsizing as much as the other carriers this year. But there will be additional fleet cuts in 2009 and 2010. US Airways has full flexibility with its E190s and is also believed to be in talks with Airbus to defer next year’s deliveries.

LCCs scale back growth plans

The likelihood that the legacy carrier capacity cuts will lead to a healthier domestic revenue environment is significantly enhanced by the fact that the US LCCs too have joined in. The LCCs are not actually reducing capacity, but they have significantly scaled down or even temporarily halted their growth plans.

This is in sharp contrast to the post–9/11 period, when LCCs took advantage of the legacy sector’s contraction and stepped up their growth plans. That resulted in the LCCs capturing significant market share and gaining pricing power — the reasons why their cooperation is now needed.

LCCs are acting differently now because they have been as devastated by the fuel price hikes as the legacies. They also have less flexible pricing models and little or no support from international operations. They need to conserve cash. However, at some point, the LCCs will have some unique growth opportunities.

Most significantly, Southwest has reduced its 2008 ASM growth to only 4% and currently envisages only 2–3% growth in 2009 (versus 7.5% originally planned). The airline has deferred some aircraft deliveries to 2013- 2015 and is accelerating retirements. This year Southwest is taking 29 737–700s and retiring "at least" 14 older 737 models.

Southwest is a very profit–oriented airline and has a goal of achieving a 15% ROI each year (not being achieved currently). The management has made it clear that the airline is prepared to halt growth entirely in 2009 if the operating environment does not improve.

The other two large US LCCs, JetBlue and AirTran, have also significantly scaled back their growth plans. Both deferred air–craft deliveries in the last week of May: JetBlue moved 21 A320s from 2009–2011 to 2014–2015, while AirTran moved 18 737- 700s from 2009–2011 to 2013–2014.

Following numerous small downward revisions, JetBlue currently expects to grow its ASMs by only 3–5% in 2008, compared with 12% last year. The fourth quarter will see a 2.8% capacity reduction. The airline is looking to sell more aircraft, down–gauge from A320s to E190s and reduce average daily aircraft utilisation by half an hour (from its current industry–leading 13 hours). JetBlue has also put a freeze on new employee hiring.

Having sold 18 aircraft since 2006, in late April JetBlue had agreements in place to sell another nine in 2008. There may be more aircraft sales in 2009 and 2010 to help further moderate growth and enhance liquidity.

CEO Dave Barger has promised that future growth will be "responsible".

AirTran, hitherto the fastest–growing of the large US carriers, has now totally suspended its growth plans, effective September and continuing "at least through 2009". After 19% ASM growth in 2007 and still 9–10% growth through this summer, the airline will reduce capacity by 5% in the last four months of this year. Next year’s capacity is currently expected to be flat to 5% lower.

AirTran has been gradually deferring orders and selling aircraft for over a year. The 18–aircraft deferral in May, six 737–700 sales in April–May and a June agreement to sell or lease out another five aircraft in 2008 have facilitated the new capacity plan, as well as providing a welcome boost to liquidity.

The smaller LCCs are also in downsizing mode. Denver–based Frontier is restructuring in Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Florida–based Spirit has reportedly warned its pilots and flight attendants that nearly half of them may be furloughed this autumn. Even the latest newcomer, Virgin America, has trimmed its fourth–quarter capacity plan by 10%, though year–over–year growth would still be 88% and there will be no impact on fleet growth or staff numbers.

The common theme for the LCCs is that they have significant fleet flexibility. Because of continued strong global demand for the 737NGs and the A320, the airlines can fairly easily sell, lease out or defer more aircraft if necessary. Likewise, they have the ability to "dial growth back up" (as JetBlue expressed it) when business conditions improve.

Tapping ancillary revenues

Given the difficulty in raising domestic fares, US airlines have been under enormous pressure to find new revenue sources.

Recent months have seen a proliferation of new fees for items that were previously included in ticket prices, such as a $25 fee for a second checked bag, as well as increases in existing fees.

These strategies moved into a higher gear in late May, when American announced a $15 fee for the first checked bag, effective June 15th. So far, at least United and US Airways have matched it. US Airways has also started charging for non–alcoholic drinks (including bottled water and coffee, all $2). Several airlines have starting charging fees of up to $50 for booking frequent–flyer award tickets.

Of course, many passengers are exempted from the baggage fees (typically the premium classes, premier–status frequent–flyers and international customers). Nevertheless, the mainstream traveller is now much more affected. The new fees represent a major shift by the US network carriers towards the Ryanair–style "pay for what you use" model.

These measures have impressive revenue- generating potential. US Airways estimates that its non–alcoholic drink and frequent- flyer mile redemption fees could bring in $300–400m annually. American expects fee hikes for various services to bring in"several hundred million dollars" in incremental annual revenue. United expects its baggage fees to generate $275m and believes that ancillary sources could contribute $1bn–plus in added annual revenue within a few years.

But some of those efforts could backfire because the leading LCCs may not join in. Even though the LCCs are trying hard to boost ancillary revenues, they are hesitant to add fees that could be seen as "nickel–and–diming" customers. Southwest has said that it will not be introducing such fees. JetBlue has added a second checked bag fee to "offset some of the extra fuel" but has said that the move affects less than 25% of its passengers and that nickel–and–diming is not consistent with its brand or policy.

Liquidity-raising needs

The good news is that all of the sizeable US carriers probably have enough cash to weather the storm at least through 2008. But, as oil prices have continued to rise, 2009 has looked increasingly problematic in terms of cash balances. Pressure has really built up to raise additional liquidity; after all, aircraft values are still holding up, financing is still available, and so on.

Continental has been on a cash–raising spree. Over the past two months, the airline has sold its remaining stake in Copa for $136m, completed a $163m public equity offering (in June, in the wake of announcing the UAL co–operation deal), collected $235m from a forward–mileage sale and raised $178m from a deal to extend a co–branding relationship. In addition, Continental is planning to refinance some debt and is looking to borrow against aircraft.

As a result, and also because of the capacity and fleet cuts, Continental’s survival prospects have improved materially. Its 2008 and 2009 losses will be smaller. In one analyst’s estimate, its year–end 2009 cash position has improved from a "perilous" $889m to a "satisfactory" $2.1bn.

At UAL and AMR, liquidity–raising has temporarily taken a back seat as the managements have focused on downsizing and trying to repair the broken revenue and cost equation. But both will need to do some cash–raising to make it through 2009.

The two largest carriers both have assets that they could sell — in AMR’s case, regional unit American Eagle, and in UAL’s case, an MRO business. Both have valuable Heathrow slots. But the turbulent credit markets have meant that there is less interest from potential investors, at least for the USbased businesses. Rather, the airlines are likely to focus on borrowing against their unencumbered assets, which total $5bn at AMR and $3bn at UAL, and doing forward mileage sales.

JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker suggested in a recent research note that forward–mileage sales (like the one Continental completed) were "one of the easiest liquidity levers most airlines can pull" and therefore likely to occur early on in the capital–raising cycle.

Baker estimated in early June that the capacity and fleet cuts announced by UAL bolstered the company’s year–end 2009 cash reserves by nearly $1.5bn. Including anticipated net aircraft proceeds of $400m, UAL would have just over $1bn in cash at the end of next year, which would still be insufficient, so UAL would obviously do much more cash–raising over the next 18 months.

US Airways is potentially the biggest Chapter 11 risk because of its lack of monetisable assets. The possibilities mentioned by analysts include sale–leasebacks on E190s, Washington National slot sales, a forward–mileage sale and a sale to United. Delta and Northwest are not expected to do much cash–raising in the near–term; they will be in a better position to do that after the merger.

Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg estimated on June 19th (when most airlines had announced their cuts) that US industry domestic capacity (30 largest airlines) would decline by 7.3% in the fourth quarter and by 2.2% in 2008. International capacity would grow by 5.2% this year.

The 7.3% decline would be well short of the 20% reduction that some analysts have considered necessary to facilitate healthy profits at these fuel prices. But it is early days yet; most airlines have indicated that they will cut deeper if necessary.