The full-blown fuel crisis

Jul/Aug 2008

Headwinds have been building for the aviation industry for some time — the weakening US and UK economies, the credit crunch, the continual increase in competition from new entrants, and the increase in fuel costs.

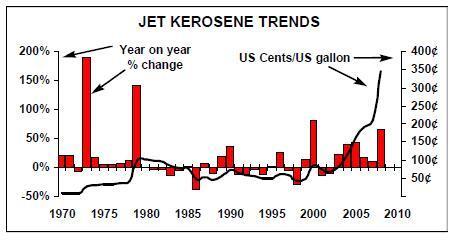

This latter headwind has now developed into a full blown crisis. Crude spot prices are currently double the average of two years ago and 65% higher than the average for 2007. At the same time the kerosene crack spread has been widening, and jet kerosene prices are currently 75% higher than the 2007 average. At this level fuel costs would represent more than 40% of total industry costs — higher even than that reached in the fuel crisis recession of 1979–81 — and could add more than $100bn to the total industry cost base on an annualised basis. All other things being equal, this could create global losses of some $95bn — and possibly bankrupt the industry.

In Europe some carriers — particularly Air France/KLM, Lufthansa and British Airways — have excellent fuel hedge positions that provide some element of protection. Some (particularly Air France/KLM, Lufthansa, British Airways and Ryanair) have strong balance sheets and good cash positions.

Two — Air France/KLM and Lufthansa — are still generating synergistic benefits from their respective acquisitions of KLM and SWISS. The Euro based carriers can afford some benefit from the dollar weakness. One consequence of the jump in fuel prices is a significant increase in working capital requirements, and some of those without these benefits are likely to be heading for a severe cash crisis — and there may even be some major bankruptcies before the end of the normally cash–generative summer season.

The likelihood is that this will also accelerate consolidation in the industry and the strong will emerge stronger from the crisis.

Fuel generally is a non–competitive element of airline operations. Historically, prices and yields have responded to changes in this input cost that is totally outside an airline’s control — albeit with an inevitable lag between price movements in fuel and the ability to change tariffs and prices. In the past few years the increases in fuel prices have been moderately high but containable. Helped by restrained capacity growth, continuing cost reductions (and Chapter 11 reorganisations in the US) and a positive economic background, the industry overall has been able to improve unit revenues comfortably to cover underlying unit cost increases. The extraordinary rise in the cost of fuel in the past six months changes this — and is redolent of the OPEC–inspired oil shock of 1979. In that year oil prices trebled: airline unit costs increased by 15% a year in each of 1979 and 1980 while unit revenues increased by 13% and 20% respectively. Thirty years on and the world is very different. IATA is no longer the pricing cartel it was. Then, the US industry had just embarked on full deregulation while there were very few international airlines outside the US in private ownership, let alone quoted. Then, almost all international routes were restricted by bilateral air service agreements, where access, service levels and tariffs were laid down by government treaty. Admittedly, there were no fuel hedging tools available.

IATA revision

Earlier this year, with crude prices hovering around $85/bbl, IATA produced a global forecast suggesting a modest fall in total profitability for the industry, after a possible industry peak in 2007. Recently at the annual IATA conference it announced a revision — based on an average of $105/bbl for the year — suggesting losses of between $4bn and $6bn for the global industry.

In this revised forecast IATA has undoubtedly assumed that the industry will be able to recover nearly two–thirds of the increase in fuel prices — primarily no doubt through fuel surcharges (or in the case of some carriers the imposition of luggage fees) — and may have made some assumptions for the prevalence of fuel hedge programmes. The industry rule of thumb is that passenger traffic grows at twice the rate of GDP — but to view this correlation as direct causation is erroneous.

There is a subtle interplay between capacity, costs, prices and income, and the big unknown is the current price and income elasticity of demand or, as some are hoping, inelasticity. (It has generally been assumed — probably more on the basis of common sense — that business traffic has a price elasticity of less than 1, leisure traffic a price elasticity of greater than 1, while both have income elasticity below 1). It appears that, all other things being equal, global air transport revenues have followed a fairly consistent proportion of world GDP — although badly hit by specific geopolitical events such as the terrorist attacks in 2001 and the SARS epidemic in 2002–3. Admittedly there was a significant jump in the ratio in the aftermath of the 1979–80 oil shock; roughly equivalent to the underlying increase in fuel costs — even though this may also partly be explained by the effects of US deregulation.

The revised IATA forecast may in the end be very conservative. On current expected capacity plans the industry suffers an estimated increase in costs of $1.6bn for each $1 movement in the price of crude oil. With crude at $140/bbl, this could mean an annualised additional $120bn above last year’s total fuel cost — equivalent to 25% of revenues — and translates into a 22% increase in overall unit costs. To put this in context, the industry probably only made a profit of $5.6bn in 2007. To cover this shortfall to merely break–even at the operating level the industry will need to increase unit revenues by some 17%.

If indeed the relationship between air transport revenues and global GDP is fixed this would require a dramatic cut in capacity on the order of 10–15%. There is always a problem with shrinking capacity in this industry so dependent on growth — a greater proportion of overheads have to be spread over the reduced level of seat kilometres flown, which automatically increases unit costs.

Even though all other things being equal this would remove the absolute need for the very deep discounted fares required to attract unnecessary traffic, it also builds in a requirement to increase unit revenues further.

Capacity cuts

As discussed on pages 9–13, the first signs of a potential capacity reduction have been signalled by major US carriers. In Europe, Ryanair has signalled its intention to stand down 10% of its fleet in the coming winter (see pages 4–8) — although this is more related to the operating costs at Stansted and Dublin and its fight with the respective airports and regulators than the age of its fleet — but it is still likely to put an additional 15% growth into the market in the off–season. British Airways has signalled its intention to cut winter capacity. In Asia/Pacific Qantas has announced a major realignment of capacity on the tourist routes to and from Japan.

One of the fundamental changes to industry operating parameters that this massive cost increase imposes is a large increase in working capital requirements. Fuel is effectively paid for in cash on monthly contract terms — the price to be paid tends to be related to the average spot prices for the previous month (with some major variations around the world depending on local conditions and delivery costs). The industry is cyclical — not merely dependent on the economic cycle but also on the seasons. Normally the lowest point of the year — in the northern hemisphere at least — is the post Christmas period: the common adage being that there are far too many wet Tuesdays in February and not enough Saturdays in August. If an airline is going to fail it is usually because of a lack of hard cash, and usually in the run up to the main summer season.

This year things may be different — with this jump in fuel prices there is probably a near 25% increase in monthly cash needs — and this is for travel through the main summer season when a large proportion of the ticket sales will have been booked well before the date of travel. We have already seen some highly publicised failures: it is likely that there are more to come.

The fuel crisis is going to have a fundamental impact on the airline industry. If we are indeed set for a period of sustained high fuel prices there will be a need for a significant cut in world capacity — and some of this will come voluntarily.

There is likely to be a substantial fall in aircraft asset prices — at least for the older generation equipment — many of which are unlikely to re–emerge from the Mojave once parked. At the same time there will be an attempt to raise fares, tariffs and yields — to which there may well be customer reluctance. The higher the price of crude goes, the greater the real danger that the US industry — only just recovered from the aftermath of the 2001 atrocities — goes into liquidation; there may not be much more room for further restructuring under Chapter 11. There have already been some calls for re–regulation in the US; and some European governments may start calling (in Italian or Greek?) for a suspension of the state aid rules.

On the other hand the rise in fuel prices may just be speculative froth, and after a few quarters of despair everything might return to normal. In the meantime the news can only be bad; the June quarter financial results are likely to be dire; there may well be another raft of bankruptcies. This may provide further impetus to industry consolidation — even though further mergers or acquisitions, outside the US anyway, may be unlikely.

The major European network carriers all have strong fuel hedge positions that grant them a competitive advantage (and one that grows the higher fuel rises), but these hedges will eventually wind down. Ryanair meanwhile — almost no matter what the fuel price — remains the lowest cost producer in what is essentially a commodity market.

| $bn | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08F | ||

| $85/b $105/ $140/ | |||||||||||

| bl | bbl | bbl | |||||||||

| Revenues | 329 | 307 | 306 | 322 | 379 | 413 | 452 | 485 | 508 | 530 | 508 |

| Fuel costs | 46 | 43 | 40 | 44 | 61 | 90 | 111 | 136 | 156 | 190 | 255 |

| Other costs | 272 | 276 | 270 | 279 | 314 | 319 | 328 | 333 | 339 | 339 | 340 |

| Operating | |||||||||||

| profits | 11 | -12 | -5 | -1 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 16 | 12 | 1 | -87 |

| Net profits | 4 | -13 | -11 | -8 | -6 | -4 | -1 | 6 | 5 | -6 | -94 |

| Brent Crude | |||||||||||

| $/bbl | 28.8 | 24.7 | 25.1 | 28.8 | 38.3 | 54.5 | 65.1 | 73.0 | 85.0 | 105.0 | 140.0 |

| 2008 anticipated | @Crude | |

| fuel burn % | equiv | |

| hedged | ||

| Air France/KLM | 78% | $55 |

| British Airways | 70% | $86 |

| Lufthansa | 85% | $70 |

| Ryanair | 3% | $70 |

| American | 29% | $76 |

| Continental | 11% | $88 |

| Delta | 36% | $95 |

| Northwest | 44% | $85 |

| United | 23% | $96 |

| Southwest | 70% | $51 |

| Source:Company reports Note: Ryanair 10% hedged for Q3 only. |

||