Alitalia: AZ Fly/AZ Services rescue mission

Jul/Aug 2005

The rescue plan approved by the European Commission in June splits Alitalia into two parts — one for flight operations (AZ Fly) and one for ground handling (AZ Services), the first of which will be privatised. After almost 60 years of operations, is this the moment that the troubled Italian flag carrier finally breaks free from government control and becomes truly competitive — or is this yet another false dawn for an airline that is doomed to bankruptcy whatever happens?

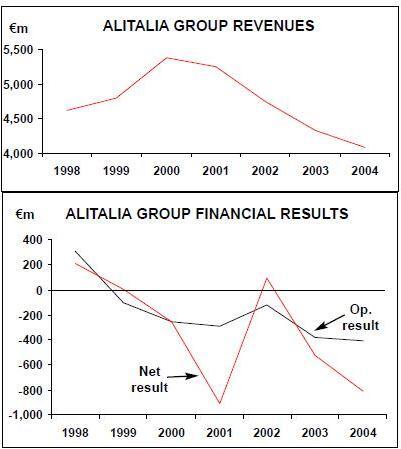

For years Alitalia has suffered from a reliance on state aid, the dubious influence of all–powerful unions and — most crucially of all — abysmal management appointed largely for political reasons by ever–changing Italian governments (see Aviation Strategy, March 2004). From the late 1990s Alitalia reported increasingly large operating and net losses, culminating in a net loss of almost €1bn in 2001 (see chart, opposite). The airline recovered in 2002 and recorded a small net profit, although this figure was boosted by asset sales and €172m compensation paid by KLM for abruptly ending a partnership between the two airlines. Alitalia plunged back into a €0.5bn net loss in 2003, and beat that in 2004 with another colossal net loss of €812m (due partly to restructuring costs). Even in the slight recovery of 2002 Alitalia had an operating loss, and it now hasn’t made an operating profit since 1998.

For 2004, Alitalia initially announced an operating loss of €402m — its highest loss since the late 1980s — but this was revised even higher, to a loss of €412m, in May this year. Revenue fell 6% in 2004 to €4.1bn, with a 1% fall in passengers carried, to 22.2m.

It’s been apparent for the best part of a decade that Italy’s flag carrier needs a major overhaul, and in fact every time the state pumped in further money this was accompanied by a restructuring or "industrial plan" of some sort. But thanks to weak management, either these plans were not implemented properly, or — much more common — the restructuring plans were not radical enough to begin with. Now, however, both the Italian state and Alitalia’s management claim that the latest restructuring effort — the so–called "rescue plan" — will improve Alitalia’s cost base and its fortunes once and for all.

The rescue plan

The rescue plan was unveiled by Alitalia in October 2004 and covers a three–year period, from mid–2005 to 2008. It envisages two stages for Alitalia: restructuring and recovery in 2005 and 2006 (with break–even in the latter year), followed by a "relaunch" and significant capacity expansion in 2007 and 2008. At the heart of the plan is cost–cutting — the aim is to reduce the cost base by €830m by 2006 and €1bn by 2008, with an overall reduction in unit costs of 20% in 2008 compared with 2005.

Key to the cost–cutting is reducing the size of the workforce, which stood at 20,700 when the rescue plan was announced last year (with 9,000 of them nominally in AZ Services and 11,700 in AZ Fly). The plan initially envisaged saving €315m in labour cost in 2005 and 2006 by the culling of 5,000 jobs — 900 in ground operations, 1,570 in flight operations (450 pilots, 1,050 cabin crew and 70 ground staff); 1,440 in maintenance, 360 in sales & marketing, 610 in corporate & IT, and 120 in cargo operations.

However — and this is a crucial point — this redundancy target has since eased back to 3,700 at best, thanks to resistance by unions and an inability by management to push through the restructuring they wanted at a time when they had the upper hand in applying pressure. In later 2004, after negotiations with six pilots' unions that had started 13 months' previously, a figure of 389 pilot job losses was agreed. The pilots also agreed to productivity improvements that see working hours rise by up to 22%. Altogether, Alitalia claims the pilot job losses and new conditions will save the airline an estimated €52m a year. A few days later the ground unions agreed to shed 2,500 positions in a deal that will cut costs by another €150m a year.

However, it took longer for the more militant cabin crew unions to agree their deal, which was eventually completed in February 2005. Although initially the rescue plan stated 1,050 cabin crew redundancies, after negotiations between management and unions this was pegged back to 900, then down to 800, and by the conclusion of negotiations redundancies were avoided altogether.

Instead, cabin crew staff have agreed to an increase in productivity, greater relocation to Alitalia’s Milan hub and a reduction in cabin crew salaries and benefits that management says will save €75m a year.

Despite these agreements, relations with the unions are not great, and many of the workforce remain suspicious about the longer–term impact of the rescue plan. Crucially, one cabin crew union did not sign the agreement with Alitalia — SULT, which represents approximately one–third of cabin crew. It argues that the new deal is harsher than similar cabin crew at other European flag carriers, and that it also compromises safety. Its members believe that if other cabin crew unions had resisted the new deal, then management would have had no choice but to give further concessions to unions. In protest, SULT members are continuing to carry out a series of industrial actions this year, and are due to carry out a one–day strike on July 18. To make matters worse, in May the right–wing Italian government introduced a law to "guarantee minimum services" in the public sector. This was supposed to prevent further action, but it merely prompted solidarity between workers at Alitalia, and pilots, cabin crew and ground staff are threatening to strike this summer in protest at the government’s restriction on the right to strike.

Alitalia has also been hit in 2004 and 2005 by strikes by air traffic controllers and airport ground staff, as well as a general strike against the government.

SULT also represents employees at Alitalia call centres, and they too have held industrial action this year in protest at the possible outsourcing of the call centres as part of the rescue plan. In March Alitalia’s management responded to increasing strike action by taking out adverts in Italian newspapers that stated that "it would be a paradox if we were to be defeated not because of external difficulties … but due to the foolishness of a few".

Yet SULT’s resistance and the government’s overreaction is encouraging pilot and ground staff unions that did sign agreements for redundancies with Alitalia last year to have second thoughts. In May staff at three other cabin crew unions held a four–hour stoppage in protest over what they see as management’s continuing failure to implement previous collective agreements, and pilot unions are believed to want to renegotiate the previously–agreed 389 redundancies in the light of the cabin crew deal that included no job losses whatsoever.

Even excluding the possibility of renegotiated agreements, it’s almost impossible to reconcile the figures of actual versus planned job losses at Alitalia. The widely quoted current figure from management is 3,700 redundancies, but even if that is accurate it just isn’t enough to make Alitalia competitive in Europe, because the company starts from a very high labour cost base.

In April this year UBS said that Alitalia’s labour unit cost was among the highest of the major European airlines (its labour costs have increased by 17% since 2002) and its productivity was below the European average.

Another analyst estimates that the company would needs to cut another 7,000 or so positions (bringing the workforce down to 10,000) for its unit labour costs to become competitive with other major European airlines.

End of state aid?

Putting concerns about labour costs aside for a moment, will the rescue plan solve another of Alitalia’s historical problems — the reliance on state aid?

The plan includes a €1.2.bn rights issue for AZ Fly, which will be guaranteed partly by the Italian state and partly by Deutsche Bank, which is jointly leading a consortium of private banks with Italy’s Banca Intensa. After the rights issue (which is now likely to be completed in October and November, even though it was supposed to be carried out by the end of July) the Italian state’s share in AZ Fly — held via the treasury ministry — will fall from 62.3% to less than 50%.

After a formal investigation into the rescue plan launched in January on the Commission’s behalf by Ernst & Young, in June the Commission ruled that the plan includes enough elements of private finance to ensure it is not state aid, although it made clear it would examine the rescue plan closely as it was adopted, to ensure that no aid crept in. The Commission also applied conditions that the state and private sector parts of the capital increase occur at the same time and at the same price, and that the state could not guarantee the private sector rights issue if it was not fully subscribed. The Commission also wants the current Deutsche Bank guarantee — which is in the form of a Letter of Intent sent in April — firmed up into a tighter commitment.

The Commission also looked at Alitalia’s use of an emergency €400m bridging loan approved in July last year, which was allowed under the conditions that it was used only to win enough time for Alitalia to restructure, that the government became a minority shareholder within 12 months, and that it was repaid by the end of this year with interest at a rate of 4.43%. Again, the Commission found in Alitalia’s favour, concluding that the loan has not been used illegally.

Other European airlines — both flag carriers and LCCs — are outraged at the Commission’s clearing of the rescue plan, which they see as a flagrant breach of the EU’s "one time, last time" rule on state aid for airlines. For Alitalia, this was supposed to have been in 1997 when it received state aid of €1.4bn — although another €1.4bn was pumped into Alitalia in 2002 after a controversial rights issue, of which €900m came from the Italian ministry of finance.

Although it is believed that some of the Commissioners — particularly those for trade and competition — were against approving the rescue plan, many of Alitalia’s rivals blame (off–the–record) the Commission’s approval on a change in policy by the new EU transport commissioner, Jacques Barrot. He appears to be taking a much softer line on state bailouts than his predecessor, Loyola de Palacio, from whom he took over in November 2004. Interestingly, in June the competition commissioner, Neelie Kroes, proposed a reform of state aid rules over the next five years.

If adopted — and that’s a big if — her proposals could force the Commission to reverse its approval of the Alitalia rescue plan.

In October 2004 eight major European airlines (unsurprisingly, mostly Star or oneworld alliance members) wrote a letter to the Commission to complain against the $400m bridging loan, and in March this year they followed that up with another letter accusing Alitalia of aggressive pricing, which was causing "severe" damage to competitors.

The European majors are now considering their position given the Commission’s approval of the rescue plan, although Lufthansa is known to be one of several carriers that are contemplating legal action.

In May European LCCs sent their own letter of complaint to the Commission, their point being that approval of the Alitalia rescue plan sets a dangerous precedent — i.e. that other flag carriers in trouble can get "state aid" if it is dressed up in a way similar to Alitalia’s plan. The same LCCs previously threatened to take the issue to the European Court of Justice if necessary.

Putting the traditional bluster of rivals aside, does the rescue plan stand up to the charge that it is state aid by another name? Alitalia is using Mediobanca and Goldman Sachs as advisors on the recapitalisation, while Merrill Lynch is advising the Italian government, and until the fine print of the rights issue is available, it’s difficult to assess whether the government and private part of the recapitalisation are being carried out on exactly the same terms. One area of concern is that in giving the go–ahead for the rescue plan in December, the Italian parliament’s transport committee said that the state’s share should not go under 30% and that it should keep "veto powers" through holding a golden share. If that were to be the case, then the public and private part of the recapitalisation would take place on very different terms.

But while much attention is focussing on AZ Fly, it is the structure of AZ Services that gives much cause for concern to some critics. Italian state holding company Fintecna is in negotiations to buy 49% of AZ Services, but the price paid must be justified in terms of what the company is truly worth on an open market. Fintecna is used by the government to restructure and privatise former wholly state–owned companies, and was brought into the deal partly due to pressure from unions concerned over the possibility of job losses over and above the 5,000/3,700 already going. Unions were insistent that state–holding company Fintecna be the main "new" investor into AZ Services.

AZ Services was formally incorporated in November last year, although Alitalia’s flight operations were not transferred across until May 1st 2005, when Roberto Renon, previously head of Italian rail company Trenitalia, was appointed chairman and CEO of AZ Services. At that date contracts were also signed between Alitalia and AZ Services with — according to Alitalia — "prices and level of service in line with market standards". AZ Services has four business units — engineering & maintenance; airport services; centralised services; and IT and telecommunications services.

There was initially a lot of concern about how Alitalia’s debt was to be divided up between AZ Fly and AZ Services. AZ Services accounts for approximately 20% of the former Alitalia business, and the worry was that if it takes more than its fair proportion of Alitalia’s debt with it, the interest burden will mean the ground services company will be hard pressed to make a profit for many years — if ever — while giving AZ Fly a much less burdensome share of debt.

In October Alitalia said that AZ Fly would retain medium- and long–term debt relevant to flight operations, including the €400m bridging loan, and according to Alitalia’s pro–forma accounts as at end 2005, a total of €425m in assets are being transferred to AZ Services, of which €245m are tangible assets, €87m are "raw materials" and €75m "equity holdings". But liabilities of €331m are also being transferred to AZ Services, and these include €36m of supplier debt, €82m of provisions for redundancies and €197m of "allowances for risks, contingencies and charges".

Quite what this last category includes is unclear, and it will be interesting to see how the net accounting assets figure for AZ Services of €94m compares with the price that Fintecna eventually pays for its 49% stake, given unconfirmed reports that Fintecna is likely to pay anywhere in the region of €150m to €300m.

However, this could be less if — according to Italian newspaper reports — AZ Services sells off its IT business to IBM for up to €50m prior to Fintecna’s investment. Negotiations on Fintecna’s stake are still continuing, although the deal is due to be completed by the end of July. Fintecna may also acquire an option to buy another 2% of AZ Services, thus giving it majority control before a flotation of part of the business sometime in the future.

However, it’s clear that whatever price is paid, as Fintecna is a government entity then AZ Services will effectively remain state–controlled (given Fintecna’s 49% or 51% share, added to the government’s major stake in AZ Fly, which will own the remaining 51% or 49% of AZ Services).

Another contentious part of the rescue plan is that the 3,700 job loses will be paid for by a state–funded social package costing anything between €100m and €450m, depending on whose estimate you believe. Alitalia’s argument is that this is not technically state aid since it is "structural support" to a restructuring industry and an extension of "Cassa Integrazione", an existing scheme that gives a minimum wage for a limited period to workers laid off in the car manufacturing industry.

Expansion goal

Even if Alitalia cuts costs as targeted, does the second part of the rescue plan — which envisages expansion in 2007 and 2008 — make sense? Alitalia currently operates to almost 100 destinations with a fleet of 180 aircraft (see table, opposite), two–thirds of which are fully–owned by Alitalia, but capacity is expected to increase by 12% in 2005,with even greater growth on both short/mediumhaul and long–haul from 2007 onwards.

Much of the capacity increase this year is coming from better fleet utilisation, which Alitalia CEO and chairman Giancarlo Cimoli (incidentally, the third CEO at Alitalia in less than a year) says is like "adding five more aircraft to our fleet". But there’s a limit as how much utilisation can improve further given that the fleet is made up of 12 different types and has an average age of 10 years.

In the relaunch phase of the rescue plan (2007–2008), the long–haul fleet will be expanded by at least five new aircraft, to a total of 34 aircraft by 2008, and the short- and medium–haul fleet by at least 10 aircraft, bringing the total to 162 by 2008. At that date Alitalia plans to have a fleet of 196 aircraft. The question has to be asked — is this a sensible move given the falling yields at Alitalia and the relatively low load factors on many routes? Surely Alitalia should be cutting back on inherently loss–making routes first, reallocating capacity to routes that have immediate prospects of being profitable? To state that in four years' time Alitalia will expand capacity by 13% sounds like poor planning — or rather making capacity promises for the sake of doing so. And that’s not to mention the problem of how Alitalia will afford to pay for the aircraft needed for new capacity, let alone the aircraft needed for fleet renewal.

Perhaps instead of planning expansion, Alitalia’s management should take a closer look at defending its position in the Italian market, where it admits it is coming under fierce attack from LCCs and almost 30 other Italian airlines. In May Alitalia said that there was continuing overcapacity in the domestic and international markets, yet bizarrely it believes it can increase its share of the domestic market, which (in terms of available capacity) stands at just over 50%. In June of this year Giancarlo Cimoli said that "a national flag carrier should not fall below a 60% to 70% stake of a domestic market", and added that Alitalia wanted to re–establish its dominance domestically.

That seems almost impossible, particularly as Ryanair is looking eagerly at the Italian market, which is one of its key domestic targets on the continent. Ryanair has been operating to the Italian market since 1998 and currently operates more than 60 routes out of 15 Italian airports.

This makes Ryanair the second–largest carrier in Italy, and it will carry an estimated 10m passengers to/from and within Italy in 2005.

Ryanair operates substantial hubs at Rome Ciampino and at Milan Orio al Serio, and these are a direct challenge to Alitalia, whose two main hubs are Rome Fiumicino and Milan Malpensa.

Nevertheless, Alitalia will press ahead with expansion at Fiumicino if Aeroporti di Roma approves a plan to give Alitalia exclusive use of Terminal A, with the other two terminals dedicated for all other airlines. However, if this move goes ahead then competitors such as Air One (which has 30 aircraft) and Meridiana (which has 21 aircraft) will have to leave Terminal A, a decision these airlines are likely to resist greatly.

In April Ryanair launched services from Rome to Venice, Verona and Alghero (in Sardinia), at average fares of €10–15 per ticket, which Ryanair claims is 80% less than Alitalia’s fares on those routes. At the press launch of the services, Michael O'Leary — Ryanair’s CEO — wore a t–shirt with "Arrivederci Alitalia" on it, and he added that he was aiming for at least 0.5m passengers on the three routes in the first year of services.

Other competition comes from easyJet, which operates 27 routes to Italy, and Milan–based Volare, the Italian group that included LCC Volareweb.com and charter carrier Air Europe. Although Volare went into bankruptcy administration in November 2004, it resumed flights in December and relaunched in June as a primarily domestic non–LCC airline connecting Milan Linate and Malpensa with regional airports in the south of Italy. With a slimmed down workforce of less than 200 employees and leased A320 aircraft, Volare’s seats are distributed via the internet and call centres. In March, however, an Italian cabinet minister said Volare was likely to sign a commercial agreement with Alitalia.

Although more than half of Alitalia’s 22m annual passengers fly on domestic routes, Alitalia appears relatively unconcerned about the threat from Ryanair and others, and instead appears to be confident that it can somehow increase market share. If that’s to happen, much depends on expansion plans for fully–owned subsidiary Alitalia Express, which was launched in 1997 and operates regional feeder routes and charter operations for its parent.

Alitalia Express operates a fleet of 35 ATR and Embraer aircraft, and in March 2004 acquired the assets of bankrupt regional carrier Gandalf Airlines for a reported sum of €7m. Gandalf was launched in 1999 and operated a fleet of 328JETS and Fairchild Dornier 328s, but never came close to making a profit. Under the rescue plan Alitalia Express will become part of AZ Fly, and management at the regional airline say that their operations will be not be affected by the reorganisation.

Alitalia Express employs 700 staff, and may increase that to 800 as services expand (with, ironically, the extra flight staff coming from the 3,700 made redundant at Alitalia). In 2004 Alitalia Express received six Emb170s, but let options for six more of the type lapse. However, the airline says it needs further aircraft, although fleet expansion will only take place once/if the finances of AZ Fly are sorted out under the rescue plan.

In Europe too, Alitalia is facing what is describes as "further pressure on ticket prices especially due to the further establishment of the LCC phenomenon and the extremely aggressive pricing policies adopted by leading full service competitors". Yet Alitalia is trying to build up business into eastern Europe, and in 2004 increased frequencies on routes to Romania, Albania, the Czech Republic, Serbia and Poland, and launched new services to Russia, Hungary, Croatia and Macedonia. From June 2005 Alitalia also began code–sharing with Aeroflot on seven flights–a-week on the Milan–Moscow route; this is part of the process by which Aeroflot is being drawn into the SkyTeam alliance. But despite a 40%+ increase in capacity to eastern European destinations in the last quarter of 2004, traffic has only increased by a quarter — which either indicates there is just not enough traffic to go round these new routes, or else Alitalia is overpriced compared with its competitors. For short- and medium–haul Alitalia has 70 MD- 80s, but these could be a massive liability if, as some analysts expect, European airports start to ban the aircraft in order to comply with new environmental regulations on noise and air pollution that come into force in 2006.

A short–term solution can be found by using A320 family aircraft to/from airports that introduce an MD–80 ban, but at some point Alitalia will have to decide either to fit quieter engines — which will cost around €3m per aircraft — or replace the fleet. The former option may be too expensive for the airline, and it is more likely to gradually retire or sell the MD–80s, which have an average age of more than 20 years.

On long–haul, Alitalia has a fleet of 29 aircraft, but its network is not focused, with a handful of routes in each of Asia, Africa, North America and South America. However, it added a substantial 20% in long–haul capacity last year, thanks to the launch of routes to Delhi and Washington out of Milan in the summer of 2004, followed by a three–times–a week service on Milan- Shanghai in December — a return to the Chinese market since Alitalia withdrew four years ago. In November United and American complained that the Italian government was violating the US–Italian bilateral by refusing to allow them to code–share at Milan Linate — whereas Alitalia operates to the US with its code–share partners.

American wants to code–share with oneworld partner British Airways on London Heathrow- Linate and United would like to code–share with Star partners BMI on Heathrow–Linate and with Lufthansa on Frankfurt–Linate.

Air France/KLM?

Air France/KLM has long been considered a white knight for Alitalia by some observers — most of them in successive Italian governments — but the reality is likely to prove different.

Alitalia began code–sharing with Air France in 2001, joined SkyTeam the same year (12 months after the global alliance was launched) and in 2003 acquired 2% of Air France. However, relations with the "KLM part" of the merged airline are more complicated — Alitalia’s previous partnership with KLM was terminated in 2000 after serious disagreements about a delay in privatisation and problems at Milan Malpensa.

Air France/KLM is reportedly interested in increasing its stake to 20% prior to a full merger, but this is probably wishful thinking on the behalf of controversial Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, who has often called for the two airlines to become a single company. In January this year he said that Air/France KLM and Alitalia are "aiming for integration towards a single airline" — a remark that caused Alitalia’s share price to rise 10%, forcing the Milan stock exchange to suspend the airline’s shares. (And Berlusconi almost scuppered the Commission’s approval of the Alitalia rescue plan in April by announcing in it had approved it actually had been!) Although the subject has been discussed by the two countries' politicians, Jean–Cyril Spinetta — CEO of Air France/KLM — says: "The subject is not on the table at all." Air France/KLM sources indicate that another investment in Alitalia is inconceivable until solid evidence that the rescue plan is not only being carried out, but also is being carried out successfully.

A full merger of Alitalia into Air France/KLM is even further away, primarily because Alitalia needs Air France/KLM rather more than Air France/KLM needs Alitalia. The only real asset that Alitalia offers Air France/KLM is its domestic network — a network that is increasingly under fierce attack from competitors. In any case, Air France/KLM can probably get as much out of Alitalia via code–sharing and other agreements rather than the commitment of a risky full merger.

A pointer to what can be done short of a merger comes from a revenue and cost sharing programme that the airlines carry out on Italy–France routes. Alitalia sources have suggests that this deal may be renegotiated once the rescue plan is implemented, in order to get more favourable terms for Alitalia (the current deal is reviewed by both airlines every six months), but that may be pushing Alitalia’s luck too far.

The Air France/Alitalia deal has already been criticised by easyJet as ensuring a virtual monopoly on France- Italy routes. easyJet previously tried to win slots at Paris Orly that the Commission forced Air France and Alitalia to give up as a condition for approval of their alliance, but the slots were awarded to Volare, and easyJet appealed unsuccessfully against the decision in April 2004.

Other potential merger candidates are being bandied about in Italy, but most of these are nothing more than unsubstantiated rumours. Last year Lufthansa was mentioned by the Italian transport minister as a potential partner for Alitalia, and one that would be better strategically than Air France.

Again, this appears to be a less than useful comment by a member of the Italian government, and Lufthansa code–shares with Alitalia rivals Air One and owns regional airline Air Dolomiti.

There have also been repeated reports that government sources indicate that Emirates may be interested in a stake in Alitalia — a claim that the Middle Eastern airline denies. However, according to other reports in May this year SULT — the cabin crew union — had tentative discussions with a Dubai–based investment company called Istithmar over a potential investment.

A future?

Alitalia expects a more "positive" performance in 2005, underpinned by the saving of €170m in labour costs this year thanks to the new agreements with unions (assuming they are not renegotiated).

Nevertheless, The airline will not break–even, and is forecasting an operating loss of €100m, This still implies a significant improvement for the rest of 2005, since in the first three months of the year Alitalia racked up an operating loss of €120m (although that was better than the €190m operating loss in 1Q 2004), despite a 9% rise in revenue during January–March 2005.

The first quarter pre–tax loss before extraordinary items totalled €134m, compared with a €206m loss in 1Q 2004. Alitalia says the improved result is due to a combination of an increase in productivity, cost savings and better fleet utilisation. Labour costs fell7% in the first quarter of 2005, based on an average staff number of 19,075 (compared with 20,700 in 1Q 2004). Overall unit costs fell 1.3% in the quarter.

RPKs rose 13.9%, slightly ahead of the growth in capacity and resulting in a 0.2 percentage point increase in load factor, to 65.3%. There was a 10.1% rise in capacity on European, north African and Middle East routes and a 21.6% rise in ASKs on long–haul routes — although on the latter this only resulted in a 16.7% rise in RPKs. On the domestic market Alitalia achieved a 11.1% rise in RPKs, although AKS grew by just 2.1%, leading to load factor growing by 4.5 percentage points. This was due to the temporary troubles at rival Volare, which helped Alitalia increase its domestic market share in the first quarter of 2005 slightly, to 52.4%.

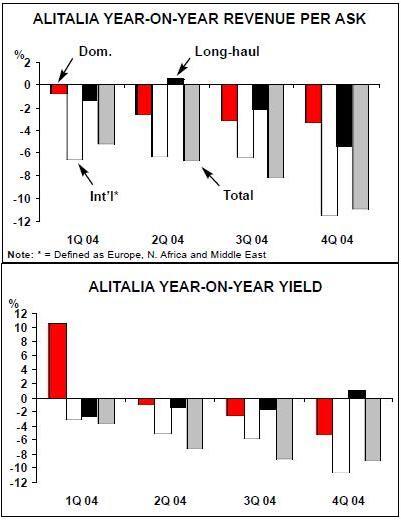

However, at the same time Alitalia also spoke of "persistent weakening of yields" through the quarter, which were 1.3% down compared with 1Q 2004, continuing a worrying trend (see chart, opposite).

The pre–tax loss before extraordinary items for the first half of 2005 is expected to be in the region of €120m, compared with a loss of €329m in January–June 2004.

Looking to the longer–term, in private few analysts give Alitalia much chance of breaking even at the net level in 2006, as the rescue plan promises. There are many reasons for that lack of confidence, not least of which was the redrafting of Alitalia’s three–year rescue plan in March, just six months after it was launched. Alitalia says this was necessary due to higher fuel costs (which are projected to be 30% higher than the fuel prices assumed in the previous plan) and the increasing threat of "low cost airlines entering the Italian domestic market", which will hit previous unit revenue estimates on short–and medium–haul routes.

No details have been released, but essentially these "new variables" mean the company has to be even more aggressive in cutting costs. But it is hard to see how Alitalia can achieve even greater cost cutting given that it didn’t achieve its original cost cutting target — i.e. the plan to cut 5,00 jobs (which has now been reduced to 3,700, and may be even lower than that).

If Alitalia doesn’t hit its cost–cutting targets — and presuming that no more "state aid", of whatever form, is allowed — then serious questions marks remain over the viability of the airline.

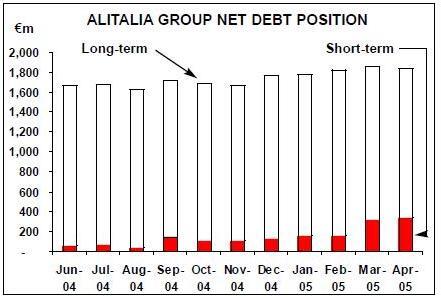

Specifically, how will AZ Fly and AZ Services be able to service the ever–increasing debt? Alitalia’s debt has become so large that the Italian stock market regulator now requires the airline to report its net debt position every month (see chart, xxx).

Group net debt (defined as financial debt minus liquid assets) at the end of April stood at a massive €1.83bn. This is €21m better than the month before but as Alitalia point out this "was mainly due to the positive effects of seasonal revenues — the start of the high season". The figure was higher than the net debt figure of €1.76bn as at the end of 2004.

And of the net debt total, a massive €609m is the current part of long–term debt, and is due to be repaid within the next 12 months (such as the €400m bridging loan, which according to the Commission now has to be paid within eight working days of the recapitalisation of AZ Fly, and in any case by December of 2005 at the latest).

It shouldn’t be forgotten that the bridging loan was desperately needed by Alitalia as in October there was only enough cash to pay the salaries of its workers for one more month. Although in fact Alitalia did avoid tapping into this facility until January this year, as at mid–April Alitalia had spent the first €155m of the loan, forcing it to drawn down the remaining €245m (which is a line of credit with the Milan branch of Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein, and guaranteed by the Italian government).

That implies a burn rate of around €40m-€50m per month. And the $1.2bn of the rights issue will not go far at AZ Fly once the bridging loan is repaid as well as other parts of the long term debt due within the next 12 months.

It’s tempting to think that the rescue plan will solve Alitalia’s underlying problems. AZ Fly will no longer be able to rely on state aid and — presumably — there can be no further weak management appointed by whichever government is in power at the time. But Alitalia’s high cost base still remains, with fewer job losses being made than envisaged when the rescue plan was put together. Despite Berlusconi’s speeches, Air France/KLM is unlikely to bail out Alitalia, and in hindsight Alitalia should have found a strategic partner during one of the few periods of profitability it had over the last two decades. But it didn’t, and its hopes now rest on the success of the rescue plan. If this doesn’t work, there can be no further state bailout, and one of the oldest names in aviation history will inevitably disappear.

| Fleet | |||||||||||

| Orders | Options | ||||||||||

| Alitalia | |||||||||||

| A319 | 12 | ||||||||||

| A320 | 11 | ||||||||||

| A321 | 23 | ||||||||||

| 747-200F | 1 | ||||||||||

| 767-300ER | 13 | ||||||||||

| 777-200ER | 10 | ||||||||||

| MD-11 | 5 | ||||||||||

| MD-80 | 70 | ||||||||||

| Total | 145 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Alitalia Express | |||||||||||

| ATR-42 | 5 | ||||||||||

| ATR-72 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Emb-145 | 14 | ||||||||||

| Emb-170 | 6 | 6 | |||||||||

| Total | 35 | 0 | 6 |