SAA looks to future after hedging crisis

Jul/Aug 2004

South Africa Airways (SAA) has undergone a roller coaster ride in the last year, after reporting a record operating profit yet becoming technically insolvent after a hedging strategy went disastrously wrong.

South Africa’s flag carrier was established in 1934 and currently operates to more than 20 destinations in Africa and 40 in the rest of the world. Transnet — the South African government’s transport holding company — owns 95% of SAA, and the airline’s employees own the other 5%, under an ESOP. (In 1999 Transnet sold 20% of the airline to SAirGroup, but in February 2002 — after the Swiss group’s collapse — the stake was sold back to the South African government.)

Almost 40% of Transnet’s revenue comes from SAA, but Transnet has 80,000 employees in total and also controls South Africa’s rail network and its ports. It is considered by many analysts to be inefficient and bureaucratic, which handicaps it in its task of overcoming decades of chronic under–investment in transport infrastructure by the country’s former apartheid governments. This is a viewpoint that many cabinet ministers in the African National Congress–led government of Thabo Mbeki also subscribe to.

In May, the government affirmed that it wanted private sector involvement in a number of state–owned enterprises, including SAA. The first step may be the unravelling of SAA away from the control of Transnet, perhaps followed by closer links with a foreign airline partner.

However, even though the government has a policy of privatisation (since 1997 the country has made Rand 34bn from selling national assets), at the moment the state is not contemplating an IPO or trade sale for SAA, which would be unpopular with the voters and trade unionists that gave a landslide majority to the ANC. If SAA is eventually put up for sale, likely bidders would include Singapore Airlines and Lufthansa, which were reported to be interested in bidding for SAA back in 1999.

In any case, a float cannot be on the agenda until SAA’s financial woes are sorted out.

Rand/dollar miscalculation

SAA’s hedging policy was designed to protect the airline from fluctuations in the Rand against the US Dollar, given that approximately 50% of SAA’s operating costs (excluding aircraft leases) are Dollar–denominated.

Historically, the Dollar has tended to rise against the Rand, and fixing the Rand against the Dollar through hedging contracts earned SAA more than $300m in the 2001/02 financial year. However, after SAA locked itself into further fixed Rand/Dollar positions (some of which last for up to 10 years), the airline saw the Rand unexpectedly strengthen against the US currency, improving from 13.6 Rand to the Dollar in December 2001 to around Rand 6.2 at present. This resulted in massive hedging contract losses of around $930m in the 2002/03 financial year, forcing the South African government to issue a guarantee for $543m of the airline’s debts to key lenders.

The hedging crisis and the government’s arrangement of a guarantee helped delay the release of 2002/03 accounts (the financial year at SAA runs to March 31st) for two months, until August 2003. Then in March 2004, SAA announced it was going to sell its hedge book (its total currency positions are reported to be worth $1.3bn) to a consortium of international merchant banks, though no further details were given.

Worryingly, the massive hedging losses only came to light after a new accounting standard (AC133) was made mandatory in South Africa. It forced all companies with large hedging positions to account for the current market valuation of those hedges in their balance sheets. SAA insists that the full extent of its loss when its positions are closed will be less than the accounting loss quoted at the end of 2002/03, but under the new standard it had to book the market value of the hedges as at financial year–end. If SAA is correct, it may be able to write–back to its balance sheet some hedging gains in the financial year just ended — although it is highly unlikely to be as much as the losses booked in March 2003.

Whatever SAA says, there is no doubt that the hedging fiasco has severely dented both SAA’s reputation and balance sheet. The strengthening of the Rand against the Dollar significantly hurt many other of South Africa’s external–facing business, but none of them had as much exposure to risky hedging policies as SAA.

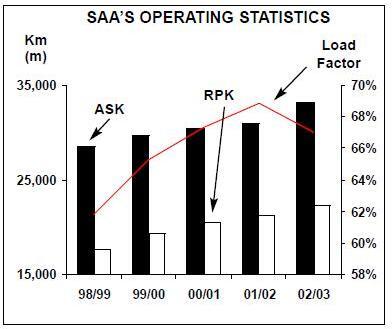

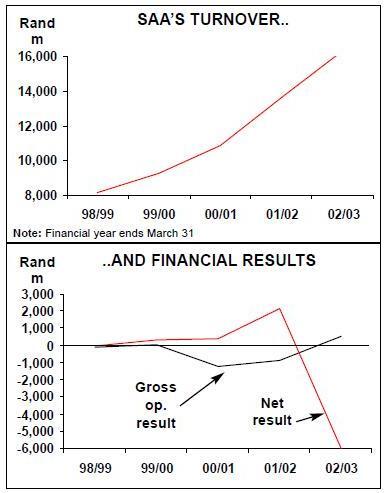

When SAA released its 2002/03 results, the hedging losses overshadowed the airlines' biggest–ever gross operating profit — of Rand 545m ($74.7m), compared with a Rand 834m operating loss in the previous financial year — see chart, below.

(Except for the North American routes, where frequencies were cut back, SAA was not affected by September 11 in the 2001/02 financial year — though its insurance costs did rise by Rand 200m a year).

In the 12 months to March 31st 2003, SAA reported airline revenue of Rand 16.3bn ($2.2bn) — 20% up on 2001/02, and due partly to tourists' perceptions that South Africa is a relatively safe destination (in global terms) and partly to one–off events such as the Cricket World Cup. 12% of SAA’s turnover comes from cargo, which is a solid if unspectacular revenue stream. At the net level the hedging loss resulted in a Rand 5,977m ($819m) loss, compared with a Rand 2,144m net profit in the 12 months to March 31st 2002. Net asset value at March 31st 2003 was a negative Rand 1.4bn, compared with a positive Rand 6bn in March 2002. The underlying operating profit was achieved through a close control on costs, which lagged the rise in revenue.

The introduction of Airbuses (from January 2003) helped reduced unit costs, but labour costs increased by 11.5% after flight deck crew received a 15% pay rise and other staff received an average increase of 9%. Yield increased by 13.8% in 2002/03 as a result of fare rises and improved revenue management, and passengers carried rose by 6% to 6.5m. Worries about SAA’s hedging policy led to the appointment of Maria Ramos, the government’s treasury director general, as CEO of Transnet in September 2003, after the previous incumbent — Mafika Mkwanazi — resigned. In October 2003, as the mounting hedging losses became apparent, Richard Forson — SAA’s CFO, who made a major contribution to SAA’s performance over the previous few years — took responsibility for the hedging policy and resigned.

Weeks later, Transnet launched an investigation into both its and SAA’s treasury operations, accompanied by the suspension (on full pay) of Johan van Schoor, SAA’s head of treasury.

The hedging scandal affects not just SAA, but also has serious implications for the whole country, as a weakening in Transnet’s balance sheet can affect South Africa’s credit rating, and hence the interest rates that the state can borrow at.

In April 2004, Transnet was forced to recapitalise SAA by a massive Rand 6.1bn ($947m), and the ongoing crisis has led SAA president and CEO Andre Viljoen’s announcement that he will step down at the end of August. It seems that Forson’s resignation did not satisfy SAA’s critics sufficiently.

Part of the justification for the risky derivatives contracts was to hedge the Rand cost of the Dollar payments SAA has to pay for 41 Airbuses it ordered back in 2002, which is part of a 10–year fleet modernisation programme (see table, opposite). Just two years' previously, SAA leased 21 737–800s , an interim measure, as SAA’s entire ageing Boeing fleet is to be replaced by the Airbuses. The first of these deliveries was an A340- 300E — the enhanced version of the -300 model — that arrived in March 2004 and was immediately put into service on the Johannesburg- New York JFK route. Of the 40 outstanding orders, five are A340–300Es, 11 A319s, 15 A320s and 9 A340–600s. Two A340–300Es will be delivered in the remainder of 2004 and the last three in the first quarter of 2005, and the A340–600 order will be completed by 2005 as well. The A320s will be delivered as the existing 737–800 leases expire, with completion by 2011. The A319s will begin delivery in August 2004, with all deliveries due by the end of 2005. The 41 Airbuses are worth an estimated $3.5bn, but SAA’s capital commitment is just $1.7bn over the 10–year period as many of the aircraft will arrive on leases (three–quarters of SAA’s fleet is on operating lease).

In February, SAA agreed a deal for the sale and leaseback of nine of the A319s, from Royal Bank of Scotland Aviation Capital.

Star move

The bulk of these new aircraft will arrive as SAA starts to see the benefits of its membership of Star. Since the collapse of SAirGroup SAA has operated outside a global alliance, and ever since then the airline has been weighing up the attractiveness of the rival camps — though SAA executives insisted that continuing as a standalone airline relying on bilateral agreements was also a possibility.

However, this was never a realistic option once the financial losses arising from SAA’s disastrous hedging policy became apparent.

The revenue boost from joining a global alliance was impossible to resist, particularly as the lucrative business travel market to and from South Africa is increasingly attracted to the network benefits of global alliances.

It soon became apparent to SAA’s management that oneworld was not a realistic option for SAA given the dominance that SAA and British Airways have on profitable routes between South Africa and the UK, so the choice was between Star and SkyTeam. SAA has close ties with members of both alliances — it code–shares with Star’s Lufthansa and bmi, and with SkyTeam’s Delta and Air France.

In March 2004, it became known that SAA had decided to join Star — though the official notification was not released until June and the airline will actually not join the alliance until 2005. SAA’s entry to Star also has to be formally investigated by the South African Competition, which will examine the impact of SAA membership on other South African airlines.

However, it is expected that the Commission will approve the move, despite any objections from SAA’s competitors.

The airline is an important addition to Star as it locks into the alliance feed traffic from SAA’s African network, filling in a key geographical gap. Equally, SAA’s membership deals a blow to SkyTeam, temporarily halting its momentum now that it has overtaken oneworld in terms of total ASKs offered by its members. Neither oneworld nor SkyTeam have an African member.

Already SAA is expanding its relationships with its Star partners — it is building on its existing Johannesburg–Frankfurt route by launching a Cape Town–Frankfurt service in August. There’s also little doubt that SAA will cancel some — if not most — of its existing code–share deals with airlines in rival alliances.

The current code–share with Delta gives SAA’s passengers access to 29 US cities via Atlanta and New York, and this is sure to be replaced by a close partnership with United and its hub at Washington DC. The Atlantic routes between South Africa and the US are crucial to SAA — the airline has a 70% market share on the sector and in 2002/03 the routes delivered $44m of profit to SAA.

It will be interesting to see how the Star linkup affects SAA’s battle with British Airways on another important long–haul sector, UK–South Africa. After a revised bilateral between South Africa and the UK (which does not change the SAA/BA/Virgin stranglehold), SAA acquired two slots at London Heathrow and increased its frequencies between the two countries.

And, in June 2004, SAA announced a code–share and FFP deal with Virgin Atlantic (to start in October), which will deal a significant blow to SAA’s domestic rival Nationwide, whose existing interline deal with Virgin is being dropped.

By the time all the new aircraft arrive, SAA aims to have secured itself an even greater dominance in the African market, in which it believes has significant potential now that the Yamoussoukro Treaty is being implemented (see Aviation Strategy, September 2003).

Intra–African passenger traffic is experiencing double digit growth at present, and aviation is slowly becoming an affordable alternative to poor rail and road transport for the more affluent.

In 2002/03 passengers carried on SAA’s African network increased by 14%.

Additionally, there is growing leisure and business traffic between Africa and the neighbouring continents, particularly northwards to Europe and eastwards to the Middle East and Asia.

African hubs

Core to SAA’s strategy on the continent is the establishment of hubs in east and west Africa, to complement the airline’s Johannesburg base. The east of Africa is particularly important, as countries such as Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda have some of the fastest–growing GDP rates in the continent. Dar–es–Salaam is the choice for the eastern hub, and in December 2002 SAA bought 49% of ailing flag carrier Air Tanzania for $20m.

Air Tanzania operates three 737s and two Dash 8s, which apart from one 737 have all been transferred from SAA’s fleet. The airlines code–share on routes between the two countries, and Air Tanzania has been reinvigorated following SAA’s buy–in. The airline relaunched in March 2003 and restarted a number of routes that had previously been dropped, including Dar–es–Salaam to Johannesburg. SAA also strengthened its east African presence via code–sharing with Ethiopian Airlines, which began in November 2003. Ethiopian flights replaced SAA’s own Johannesburg–Addis Ababa service, which it axed in September "due to low demand" after operating the route for just seven months. SAA and Ethiopian are also linking their FFPs.

The west African hub, however, is proving more problematical. The Nigeria government’s attempts to set up a successor to the collapsed Nigeria Airways (with which SAA had a troubled relationship) have so far come to nothing. In 2003 a new airline, Nigerian Global, was slated to become the replacement flag carrier.

SAA was one of a number of foreign airlines that talked with the government about Nigerian Global, and SAA was contemplating investing $50m and transferring 15 aircraft to the start–up, which would have been 49% owned by the Nigerian government (after it transferred Nigeria Airways' assets to the new airline). In the end, Nigerian Global came to nothing, although the airline was legally formed and even took delivery of an A310.

After that, another start–up — Nigeria Eagle Airline (NEA) — was planned. Again, SAA talked to the Nigerian government about becoming NEA’s "technical partner".

In fact it was reported that SAA was the only other foreign airline interested in becoming a strategic partner in the airline, which would cost at least $100m to launch. The plan was for SAA to own 30% of NEA, with another 30% earmarked for an IPO. However, in late June 2004 the involvement of SAA in this project was reportedly stopped by the Nigerian government after — according to the Nigerian aviation minister — a squabble over the relative equity stakes of SAA and Nigerian investors. There are also reports that the Nigerian government demanded — and was refused — that SAA allow Nigerian investors to buy up to 10% of the South African airline as the price for its involvement in NEA.Whatever the real reasons, SAA involvement in a Nigerian airline now appears dead, although the Nigerian government says it will still launch NEA by the end of the year regardless.

It will have to look for expertise from another foreign airline however, and unconfirmed reports from the Nigerian press claim that Virgin Atlantic is interested in the NEA project.

Nigerian Global may also be resurrected, this time with the help of private backers from Switzerland and elsewhere.

SAA therefore has to look elsewhere for a west Africa hub. The most likely candidate is Dakar, capital of Senegal. SAA has gradually introduced a stop in Dakar to some of its longhaul flights. Initially two out of seven weekly flights northbound to New York JFK called in at Dakar (aircraft from South Africa northbound to the US have to have a fuel stop) as did three of the southbound flights, but the stop was so popular that now all northbound flights refuel at Dakar, rather than the Cape Verde Islands.

It is evident from the Nigerian situation that SAA may not have it all its own way in carving up the African market. There is some concern in Africa over the strength of SAA relative to the continent’s other carriers, many of which are in financial trouble or have collapsed entirely.

SAA says its is sensitive to the criticism and plans to keep national brands such as Air Tanzania, particularly as SAA faces competition from Kenya Airways, which is also building up its east African presence and which bought 49% of Tanzanian airline Precisionair in March 2003. Kenya Airways is a long–time critic of SAA (see Aviation Strategy, September 2003), and has previously tried to set up a pan–east African airline that could provide a strong competitor to SAA across the continent.

But whatever the concern about SAA, there is much more worry in the continent about increasing competition from European and US airlines — more than two–thirds of international traffic to/from Africa is carried by non–African airlines. In that regard, SAA could position itself much more aggressively as a "Black Knight" that can preserve Africa’s aviation assets.

Outside Africa, SAA is looking to increase its presence in Asian markets, particularly India and China. SAA operates to Hong Kong, with code–shared flight into China through Cathay, but SAA would like to operate direct routes on its own. Though SAA dropped its loss–making Johannesburg–Bangkok route at the end of October 2003, this may be reinstated after SAAformally joins Star. Aroute to Singapore to connect with Star member SIA is also likely, as are services to Bombay and New Delhi sometime in 2005.

In the domestic market, however, SAA’s dominant position is coming under attack. SAA’s feeder network is operated partly by South African Express (whose operations were merged into SAA in April 2004) and South African Airlink (which SAA owns 10% of).

Airlink operates 13 BAe Jetstream 41s, four ERJ–135LRs and an F28, and has 15 more ERJ–135LRs on order. Some — if not many — of SAA’s domestic feeder routes are believed to be loss making. But SAA is facing a fare battle initiated by Comair’s LCC subsidiary Kulala.com, which launched in 2001 and operates three 737–400s domestically.

These aircraft are being transferred to Comair’s British Airways franchise operations in South Africa (BA owns 18% of Comair), to be replaced at Kulala.com by four MD–82s. Comair concentrates on point–to–point services out of its Johannesburg hub with 18 727s and 737s.

Another domestic competitor is Nationwide Airlines, which has a fleet of 13 Boeing aircraft and operates scheduled and cargo flights both within South Africa and regionally. In February 2004 another LCC — the curiously named 1time — launched operations between Cape Town and Johannesburg with two DC–9s and two MD–82s, with fares it claims are up to two–thirds cheaper than SAA. SAA is responding to the threat of these airlines by cutting fares, with an inevitable erosion to its yield, but the flag carrier believes it can withstand the LCCs by offering passengers "all the frills at no–frills prices". However, the LCCs will continue to challenge SAA, and 1time intends to launch further domestic routes through 2004.

Since 2001 SAA has also been battling a legal complaint by Nationwide Airlines that the flag carrier has allegedly been carrying out anti–competitive behaviour through paying travel agents to sell SAA tickets even if competitor fares are cheaper.

In June 2004 the Competition Appeal Court dismissed SAA’s appeal against a previous decision by the Competition Tribunal that SAA could not post–pone the hearing of an anti–competitive case against it. Once the Competition Tribunal hears the full case, if it decides against SAA it can impose a fine equal to 10% of the airline’s annual turnover, which is a huge sum. Comair has also complained about anti–competitive practices by SAA.

In response to rising fuel prices, in May 2004 SAA introduced a fuel surcharge of 28 Rand ($4.24) per domestic trip and $10 per international trip. Though there was nothing unusual in that — Comair, Kulala.com and BA also introduced surcharges — SAA looked incompetent when just a week later it increased the domestic levy to 40 Rand ($6.06).

But it’s not just domestically that SAA is facing LCC competition. In October another LCC — Stansted–based CivAir — will launch flights between London and Cape Town, to be followed two months later by a route to Durban.

Again, SAA’s existing fares will be undercut by a third. With the 2010 football World Cup being awarded to South Africa, it’s inevitable that LCCs and major airlines will ramp up services to the country. In July 2004 Virgin Atlantic announced that it was planning an African LCC, with a senior executive saying: "The market for the development of a low–cost, pan- African airline is a real possibility for the future."

Time to refocus

In September 2003, in response to the company’s perceived strategic and financial weakness, Transnet revitalised the five–member SAA board, with two members leaving and six new appointments, including Prof. Rigas Doganis, the well–respected aviation academic and consultant. In November, the management team was overhauled, with the creation of a deputy CEO position — which is held by Oyama Mabandla, an ex–UBS banker, until he steps into Viljoen’s shoes in September — and the appointment of six executive VPs.

Though the revamped team has had little time to affect the financials, analysts will be taking a close look at the underlying operating figures when the results for the year to March 31st 2004 are released. With the effects of SARS and Gulf War II (which SAA says has had "a significant negative impact), prospects for an increased operating profit are not great, but much attention will be on the effort to cut costs. Major cutting of labour costs is off the agenda at SAA, as the government believes that maintaining state jobs is crucial to South Africa’s economy (the unemployment rate is more than 30%).

SAA employed 10,800 people at the end of the 2002/03 financial year, virtually identical to a year earlier. The relationship between unions and management is generally good, although in March 2003 the airline did attempt to "modernise" labour contracts. Good relations have led to a tangible improvement in service levels, which has led to SAA being given a series of industry awards.

However, cost–cutting progress is expected in other areas, particularly as yield erosion is expected in the domestic market. For example, SAA has been focusing on IT spend, where in 2002/03 costs jumped a massive 38% to Rand 623m after SAA hired EDS following the ending of the previous agreement with Atraxi Africa, which was owned by SAirGroup.

Analysts will also be studying SAA’s cash flow position. In 2002/03, SAA had a positive cash flow from operating activities of Rand 840m, down by just Rand 14m on the previous financial year. But heavy investment in aircraft and other items of Rand 5.8bn was not matched by an equivalent amount of new financing, so cash and cash equivalents fell substantially over the year, to Rand 793m as at March 31st 2003. This will be boosted by Transnet’s Rand 6.1bn injection in April 2004, but the cash position as at March 31st 2004 will tell much about how SAA has fared operationally over the previous 12 months.

The 2003/04 financial results were scheduled to be unveiled in May, but — like the previous year — these have been delayed until August at the earliest, probably because SAA wants to announce the details of the hedge book sale at the same time (thus removing the liabilities from the airline’s balance sheet, allowing management to refocus on operational and strategic matters). As new CFO Triphosa Ramano said: "Instead of running an airline we essentially became 'South African Airways Financial Services Group' ".

Once the hedging losses are taken off the books, SAA will have a clear run at cementing its position as the number one airline in Africa.

| Fleet | Orders | |

| A319 | 11 | |

| A320 | 15 | |

| A340-300 | 15 | 5 |

| A340-600 | 9 | |

| 737-200A | 10 | |

| 737-800 | 19 | |

| 747-400 | 8 | |

| Dash 8 Q300 | 6 | |

| CRJ200ER | 6 | |

| Total | 64 | 40 |