KLM: its unequal struggle to join the Euro-elite

July 2000

KLM has always struggled in its attempts to join the European elite, because size does matter. The European scheduled full service airlines have always fallen into two groupings, in size if not always in terms of profitability. Air France, British Airways and Lufthansa are 58% bigger on average in terms of RPKs than the next largest European carrier, KLM, and 61% bigger in terms of annual revenues than the next largest European carrier, SAir Group.

The failed merger with Alitalia, which would have ranked the combined airline second behind British Airways in RPK terms and third ahead of Air France in terms of annual revenues, was, it now appears, the last gasp attempt for super–stardom in its own right. Chief executive Leo van Wijk’s statement to the effect that KLM is looking for an airline partner and that KLM would be happy to play a junior role in such a partnership suggests that KLM has downgraded its ambitions. Of Europe’s second–tier flag–carriers only SAir Group, with its strategy of building up a portfolio of minority stakes in smaller airlines, still has the ambition to join the big three.

During the 1990s KLM enjoyed two great advantages over most of its rivals. First, KLM had in Schiphol one of Europe’s premier hubs in terms of quality and convenience (operating as a single terminal). Second, the Netherlands was ahead of the game in signing an open skies agreement with the US in 1992, and negotiating antitrust immunity in 1993, which has allowed KLM and Northwest (and more recently Continental) to become industry leaders in terms of alliance development.

The Schiphol hub growth strategy worked well for a period. The single terminal and the operational freedom to build up a six–wave system made using KLM and Schiphol an attractive proposition for connecting and transfer passengers. Moreover, KLM was offering this product at a time when many of its closest competitors were in financial and strategic disarray.

In the mid–90s, with KLM uk (previously Air UK) successfully siphoning off traffic from the UK, and using other airlines such as KLM Cityhopper, Eurowings and Air Excel to enhance its network reach, KLM went for growth. Between 1995 and 1998 KLM increased its intra–European ASKs by an average of about 11% a year.

This growth surge, however, depended more and more on attracting price–sensitive transfer traffic. As neighbouring competitors such as Air France and Sabena began their recoveries, and BA, Swissair and Lufthansa also adopted growth strategies aimed at capturing transfer traffic market share, things began to go wrong for KLM. Also, the Asian crisis affected KLM more than the other European flag–carriers because of its relatively high exposure to Southeast Asian markets.

Profit decline

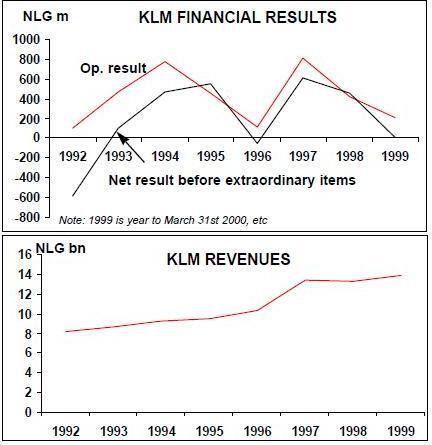

Yet Schiphol itself remains a jewel in KLM’s crown. The airport continues to win awards from business travel magazines. Environmental and safety issues have been resolved which means that the airport can handle expected traffic growth in the near future at least. And following an agreement with the Dutch Government signed in December 1999, the airport is being prepared for privatisation, which may result in a more favourable pricing regime for KLM. KLM’s results have been on a steady decline since 1997/98 when KLM recorded a pre–tax profit, before extraordinary items, of NLG 531m ($238m). That year was very successful thanks to what has proved a one–off set of factors.

In 1997/98 KLM added 5% capacity, but traffic rose by 8% boosting the overall load factor by 1.9 points to a record 77.9%. Unit costs rose by what would now be regarded by an unhealthy 4% but remarkably KLM’s yield jumped by a dramatic 10%. So despite the first signs of weakness in the Asian markets, KLM enjoyed a 20% increase in passenger revenues and a 13% increase in cargo revenues. Unfortunately for KLM 1997/98 has proved to have been a statistical blip and when profits have been in sharp decline.

In the past two years KLM has recorded overall load factors that remain well above the European airline norm, 75.1% in 1998/99 and 76.7% in 1999/00. And, excluding fuel, KLM has been able, thanks to its cost cutting programmes, to show reasonable cost discipline.

However, KLM suffered in 1998/99 from a sharp downturn in its yields, with a year on- year fall in unit revenues/ATK of 4.9%. Adverse currency movements added to its problems, and airline’s pre–tax profits (excluding extraordinary items) more than halved to NLG 244m.

Cost attack

In 1999/2000 the downward trend continued with KLM recording a pre–tax loss (before extraordinary items) of NLG 38m ($17m). Although KLM was able to reverse the decline in yields, a like–for–like increase in the annual fuel bill of NLG 235m largely accounted for the move from profit to loss. KLM is now concentrating on a drive to reduce its unit costs. The airline has stated that it "expects no material improvement in the current operating environment" which it can be taken to mean that yields will continual to fall in real if not actual terms. A rise in the airline’s break–even load factor for the year 1999/00 to 75.1% from 70.7% a year earlier is a major cause for concern.

The cost reduction programme has three themes:

- Network rationalisation;

- Evaluation of activities on the basis of the value they generate; and

- Temporisation of investments (i.e., don’t spend any more money)

KLM will freeze capacity growth this summer and forecasts a 5% fall in winter 2000/01 capacity. Eight unprofitable routes are being eliminated and seven aircraft (four widebodies and three narrowbodies) will leave the fleet. These actions are expected to improve network results by an estimated NLG 200m.

The capacity shrinkage will be accompanied by a trimming of staffing levels. KLM is also seeking in its own words (or those perhaps of its management consultants) to reduce overhead by "de–complexing organisation and processes". An additional NLG 500m in cost reductions are being sought which, again in KLM’s words will "stop the bleeding", These measures have a short–term focus but KLM recognises that "further structural measures are necessary" if the airline is to remain competitive.

The results of the cost saving programme are already bearing fruit. Excluding fuel and currency, KLM produced a 3% fall in unit costs in the fourth quarter of the last financial year. So, despite near record fuel price levels (which had a negative impact on the quarter of NLG 128m), KLM recorded a year–on–year NLG 55m improvement in operating profits. The year–on–year gains were achieved thanks to a NLG 150m increase in traffic and a NLG 47m improvement in yields.

Vanguard management and the alliance experience

With improving market conditions, thanks to a more restrained capacity policy of KLM’s major competitors, and the cost improvement programme, KLM is forecasting an improvement in operating profits in 2000/01. KLM management has tried to be at the vanguard of strategic airline thinking. KLM has always been regarded as a market leader, at least by European standards, in terms of its development of its hub and spoke system, introduction of cost saving programmes, alliance development, use of regionals to provide feed, and its emphasis on the cargo market.

KLM has come to a similar analysis of the market as BA, recognising the need to concentrate on the most profitable segments and downsize or outsource the low–yielding segments. Although KLM made headlines by announcing that it was downsizing its operation in 2000/01 in order to improve its average yields, KLM had long since abandoned its high growth strategy. In 1998/99 capacity growth, measured in ASKs, increased by only 3.3% and in the last financial year by 2.6%.

BA and KLM are companies that know each other well. The two airlines held merger talks in 1991 that collapsed the following year when the two parties could not agree about valuations. In the light of BA’s recent problems , it is interesting to note that in 1992 KLM was asking for 35–40% of the merged vehicle, while in the current round of talks it will reportedly be content with a 30% share.

Failure to do a deal with BA did not deter KLM to in its efforts to gain a larger platform in Europe. In 1993 KLM was central to the planned Alcazar project that would have seen KLM join forces with Swissair, SAS and Austrian, but once again valuations proved an insurmountable hurdle. So KLM management concentrated their efforts across the Atlantic.

The relationship between KLM and Northwest was very strained at board level during the period KLM when had a shareholding in Northwest. However, at an operational level KLM and Northwest have proved very amicable partners. Northwest and KLM have in effect operated as one carrier on the North Atlantic, pooling all revenues and costs. In this operation they have achieved far more that any other transatlantic pairing.

In 1997, the board–level differences between KLM and Northwest were resolved when Northwest agreed to buy back KLM’s 19% stake (which was completed in 1998), and both carriers signed a ten–year co–operation agreement.

KLM has sought to extend its sphere of influence in Scandinavia. Its purchase in 1997 of a 30% stake in Norway’s largest domestic carrier, Braathens, provoked an aggressive war with SAS. Braathens bought two Swedish carriers, Transwede in 1997 and Malmo Aviation in 1998, and KLM had encouraged Braathens to mount a serious challenge to SAS in its home markets.

Unfortunately for KLM, SAS has proved an aggressive competitor with deep pockets and Braathens has been forced to withdraw some capacity in the Scandinavian markets (see Aviation Strategy, March 2000). A bloodied Braathens recorded a $80m net loss in 1999.

KLM uk, which KLM has used as a feeder of UK traffic over its Schiphol hub was bought outright by KLM in 1997. Unfortunately for KLM uk, its main hub at Stansted has become the low cost airline centre in the UK, with rapidly expanding Go and Ryanair operations. KLM’s response in January 2000 was to launch its own low cost airline, Buzz, which in effect split KLM uk in two. Many expect that Buzz will eventually take–over most if not all of KLM uk operations. Whether Buzz, which operates a fleet of BAe 146 aircraft, will prove a success remains unknown. KLM hopes are that Buzz will break even in 2001,

In 1996, KLM took a 26% in Kenya Airways, which was privatised at Kenya Shillings 11.25. Unfortunately Kenya itself is in crisis with drought, famine, rampant crime and an economy in recession.

KLM’s equity links with the Dutch Government were minimised in 1998 when the airline bought back its 8.5m shares (about 12% of the airlines equity), at the same time acquiring 4.8m participation certificates from the KLM Flight Personnel Pension Fund Foundation.

The decision, which was made when KLM’s shares were trading in the low NLG 90s was made because KLM had a large cash surplus following the sale of its holding in Northwest. The fact that the shares hit a low of NLG 39.3 earlier this year makes this, with the benefit of hindsight, a very expensive buy–back operation. Moreover, KLM has continued to use its surplus cash resources to buy back its own shares: in the past two years KLM has redeemed NLG 1bn of its shares resulting in a 50% decrease in the number of shares outstanding.

The BA question

The deal with Alitalia that was first announced in December 1997 and abandoned on April 28th 2000 (for details of the KLM/Alitalia virtual merger structure, see Aviation Strategy, September 1999). The reasons given by KLM for its abandonment were serious concerns over the development of the Malpensa hub and delays in the Alitalia privatisation programme. Perhaps more importantly, KLM felt that Alitalia’s poor financial performance (the Italian carrier recorded a net loss equivalent to US$124m in 1999 and the first quarter of 2000 saw a further loss of US$74m), coupled with perhaps an closer insight into Alitalia’s senior management team, led to KLM’s decision to withdraw. Given KLM’s and BA’s chequered history with regard to alliances, what are the chances of success this time around?

First of all it should be noted that the two management appear to be taking the venture very seriously. Getting some clarification on the regulatory front is obviously a priority, and to this end, Leo van Wijk and Rod Eddington have visited Competition Commissioner Mario Monti to outline their merger plans.

The key to this merger is cost savings rather than putative revenue enhancement through route rationalisation. According to an analysis by Chris Tarry of Commerzbank, the immediate target for a merged airline would be a reduction of 16,200 employees from a combined BA/KLM workforce of 98,000.

This would generate annual savings in the order of $850m (about 4% of joint revenues). Then further savings could be achieved through route rationalisation and the removal of some aircraft from the joint fleet — estimated at an annual saving of around $50m per aircraft.

However, there is a substantial cost associated with this rationalisation. Assuming redundancy packages reflecting two and half year’s pay, this could add up to $1.6bn.

There appear to be no quick fixes through transferring traffic from London to Amsterdam. Tarry points out that, as KLM’s average break–even load factor is about eight points higher than BA’s, it would find additional low–yield traffic to be intrinsically unprofitable,

If a merger does take place, however, there should be some possibilities for yield enhancement — if only because a element of competition would be removed from the European market. Then the carriers could perhaps harmonise their downsizing strategies.

All in all, there may be just too many uncertainties and potential conflicts, both from the regulators and the unions, for this merger to go ahead. Both sets of managers are under pressure to produce results for their shareholders, and diverting precious management time into this project may not be acceptable.

| Current fleet | Orders | Remarks | |

| 737-300 | 17 | ||

| 737-400 | 19 | ||

| 737-800 | 4 | 9 | 4 in 2000, 5 in 2001 |

| 737-900 | 0 | 4 | 2001 delivery |

| 747-200 | 10 | ||

| 747-300 | 2 | ||

| 747-400 | 20 | 4 | 2000-2003 |

| 767-300 | 12 | 1 | 2000 from ILFC |

| MD-11 | 10 | ||

| Total | 94 | 18 |